Margaret Atwood Releases an Unburnable Edition of The Handmaid’s Tale, to Support Freedom of Expression

When first published in 1985, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale drew acclaim for how it combined and made new the genre conventions of the dystopian, historical, and fantasy novel. But the book has enjoyed its greatest fame in the past decade, thanks in part to a 2017 adaptation on Hulu and a sequel, The Testaments, published two years thereafter. It’s even become prominent in mass culture, frequently referenced in discussions of real-life politics and society in the manner of Nineteen Eighty-Four or Fahrenheit 451.

Like George Orwell and Ray Bradbury’s famous works, The Handmaid’s Tale also seems at risk of becoming less often read than publicly referenced — and therefore, no small amount of the time, publicly misinterpreted. The only way to fortify yourself against such abuse of literature is, of course, actually to read the book. Fortunately, The Handmaid’s Tale is now widely available, unlike certain books in certain places that have been subject to bans. It is against such banning that the latest edition of Atwood’s novel stands, printed and bound using only fireproof materials.

“Across the United States and around the world, books are being challenged, banned, and even burned,” says publisher Penguin Random House. “So we created a special edition of a book that’s been challenged and banned for decades.” This uniquely “unburnable” Handmaid’s Tale “will be presented for auction by Sotheby’s New York from May 23 to June 7 with all proceeds going to benefit PEN America’s work in support of free expression.” You can bid on it at Sotheby’s site, where as of this writing the price stands at USD $70,000.

Penguin has experimented with physically metaphorical books before: the paperback edition of Nineteen Eighty-Four, for example, whose cover becomes less “censored” with use. More recently, the graphic design studio Super Terrain published Fahrenheit 451, its title long a byword for book-burning, that only becomes readable with the application of heat. But it’s Ballantine’s 1953 special edition of that novel, “bound in Johns-Manville quinterra, an asbestos material with exceptional resistance to pyrolysis,” that truly set the precedent for this one-off Handmaid’s tale. Those making bids certainly understand the book’s place in today’s cultural debates — but let’s hope they also intend to read it.

Related content:

Pretty Much Pop #10 Examines Margaret Atwood’s Nightmare Vision: The Handmaid’s Tale

An Animated Margaret Atwood Explains How Stories Change with Technology

An Asbestos-Bound, Fireproof Edition of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953)

The Cover of George Orwell’s 1984 Becomes Less Censored with Wear and Tear

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...Terry Gilliam Visits a Video Store & Talks About His Favorite Movies and Actors

Letting a beloved film director wander through the aisles of a well-stocked video store feels like such guaranteed YouTube fodder that it’s a surprise it really hasn’t been done until recently. But then I remind myself that the video store itself is a thing of the past, and to see one so well stocked, Library of Alexandria style, is news itself. For the above video, the director browsing the DVDs is none other than madcap genius Terry Gilliam. The video store is Paris’ JM Video. The chat as expected is marvelous. (Only 20 minutes? I’m sure many of us could listen to Gilliam rabbit on about his favorite films for twice, thrice that.)

Along the way, here are some things we learn:

- Some of his favorite filmmakers are Stanley Kubrick, Lina Wertmuller, Federico Fellini, and one of his current friends, Albert Dupontel, the French actor-director who has used Gilliam in several of his films.

- He is thanked in the credits of Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs. Why? Because when Tarantino was at the Sundance Institute with his script, it was only Gilliam who immediately saw the brilliant screenplay for what it was, and encouraged Tarantino to stay true to himself.

- He’s not a fan of Die Hard, but it was the scene where Bruce Willis talks to his wife while picking glass shards out of his foot that revealed a vulnerability in the actor. It led to Gilliam casting Bruce Willis in 12 Monkeys. Similarly, he was able to work with Brad Pitt and get him to flip his cool and handsome demeanor on its head for the manic co-starring role.

- Gilliam stole the idea of multiple actors playing the same title character in The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (after lead actor Heath Ledger died during shooting) from Luis Buñuel’s

That Obscure Object of Desire. In that film, two women play the same character interchangeably. If it’s good enough for Buñuel… - Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible (parts one and two) is a “dangerous” film, because it was one of Putin’s most watched movies. (Not that we should stop watching Eisenstein.) Gilliam’s way of pronouncing Putin as “poutine” is intentional, no?

- Being a fan of Monty Python was a good way of getting cast in a Gilliam film. The director knows he would have not worked with Sean Connery (in Time Bandits) or Robert DeNiro (in Brazil) if both didn’t know his work on the classic comedy. (It also helps to have producers who go golfing with A‑list actors.)

- He disses Christopher Nolan (“technically brilliant” but then “the films become video games” with “no gravity”), and repeats a swipe against Spielberg’s Schindler’s List that he heard from Kubrick. (“It’s a film about success.”)

- He imagines a better closing edit to Close Encounters that ends upon seeing the legs of the alien as the hatch opens. Then we would have had something to talk about on the way home, he says.

There’s another video in the series featuring David Cronenberg, along with visits from Michael Bay, Asghar Farhadi, Audrey Diwan, Dario Argento, and many more.

Related Content:

Terry Gilliam Reveals the Secrets of Monty Python Animations: A 1974 How-To Guide

Terry Gilliam Explains His Never-Ending Fascination with Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus”

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

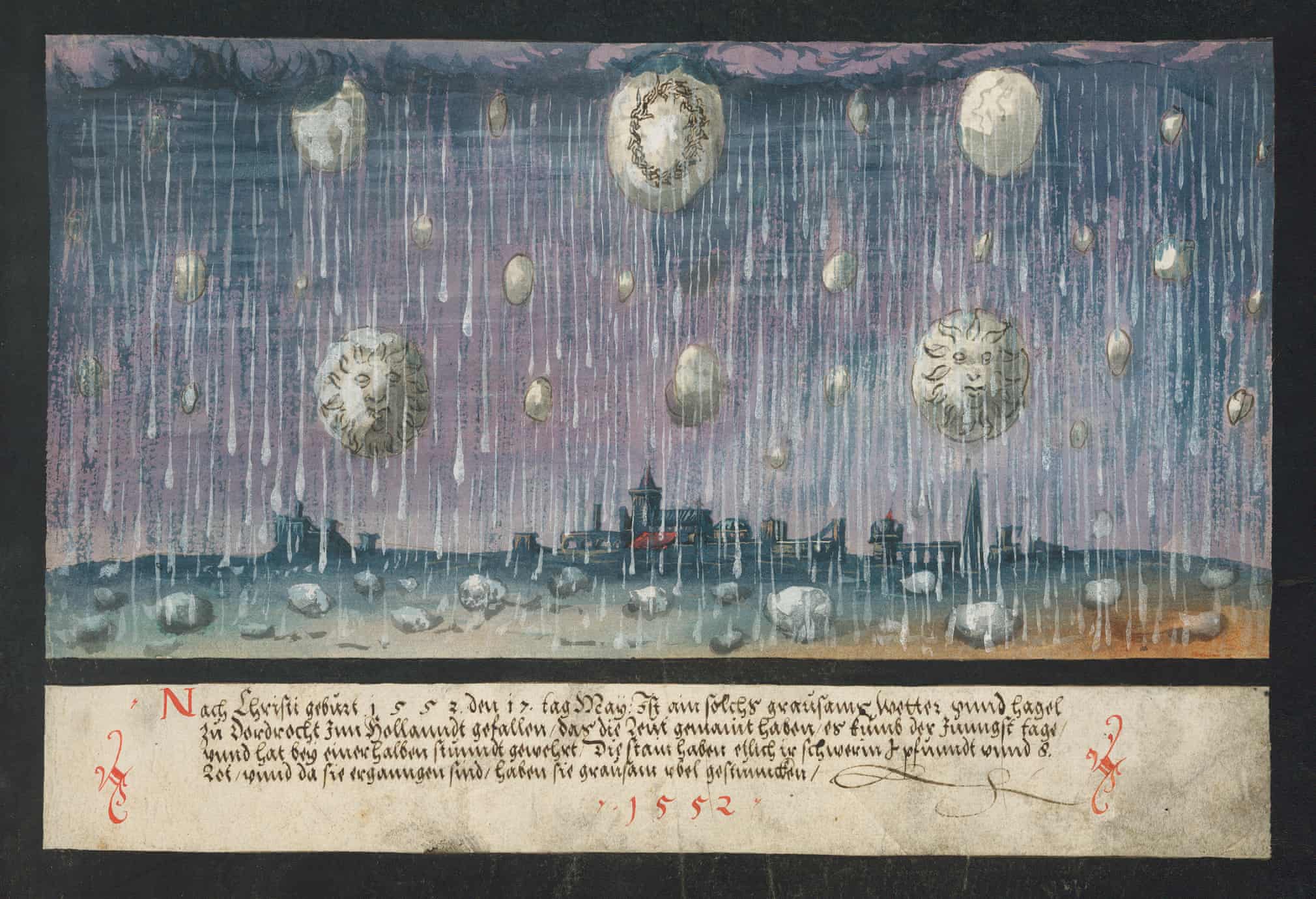

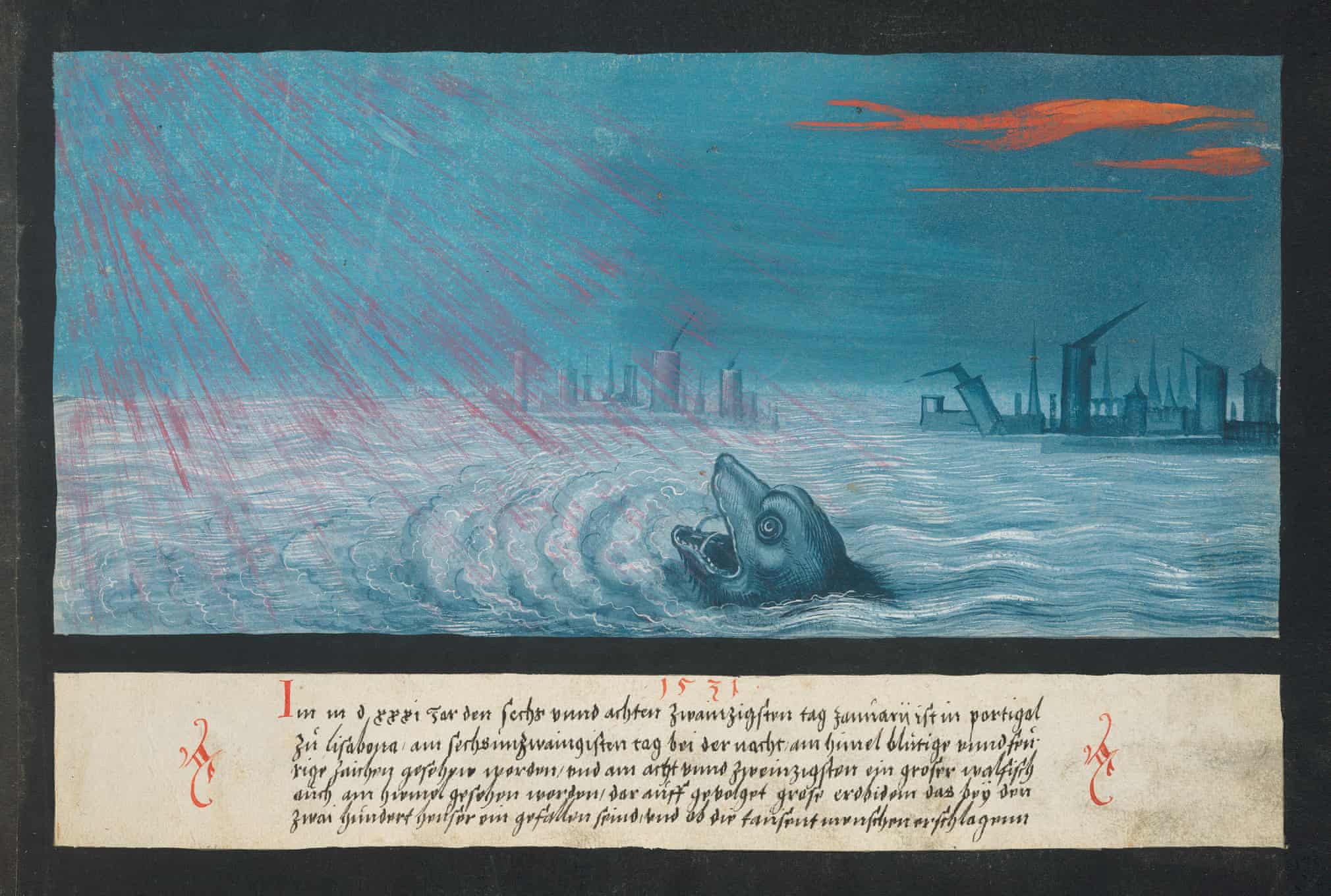

Read More...Behold the Augsburg Book of Miracles, a Brilliantly-Illuminated Manuscript of Supernatural Phenomena from Renaissance Germany

When we speak of a “lost art,” we do not always mean that humans have forgotten certain production methods. Modern craftspeople can recover or reasonably approximate old techniques and materials, and produce artifacts that can be passed off as authentic by the unscrupulous. The spirit of the thing, however, can never be recovered. Try as they might, scholars and conservators will never be able to enter the mind of a Medieval scribe or manuscript illuminator. Their social world has disappeared into a distant mist; we can only dimly guess at what their lives were like.

Thus, for many years, the reception of Hieronymus Bosch — the bizarre fantasist from the Netherlands whose visions of Earth, Heaven, and Hell have amused and terrified viewers — stressed the proto-Surrealism of his work, assuming he must have had other intentions than proselytizing.

Most recent interpretation, however, has pulled in the other direction, stressing the degree to which Bosch and his contemporaries believed in a universe that was exactly as weird as he depicted it, no exaggeration necessary; emphasizing how Bosch felt an urgent need to spare viewers of his work from the fates he showed in his art.

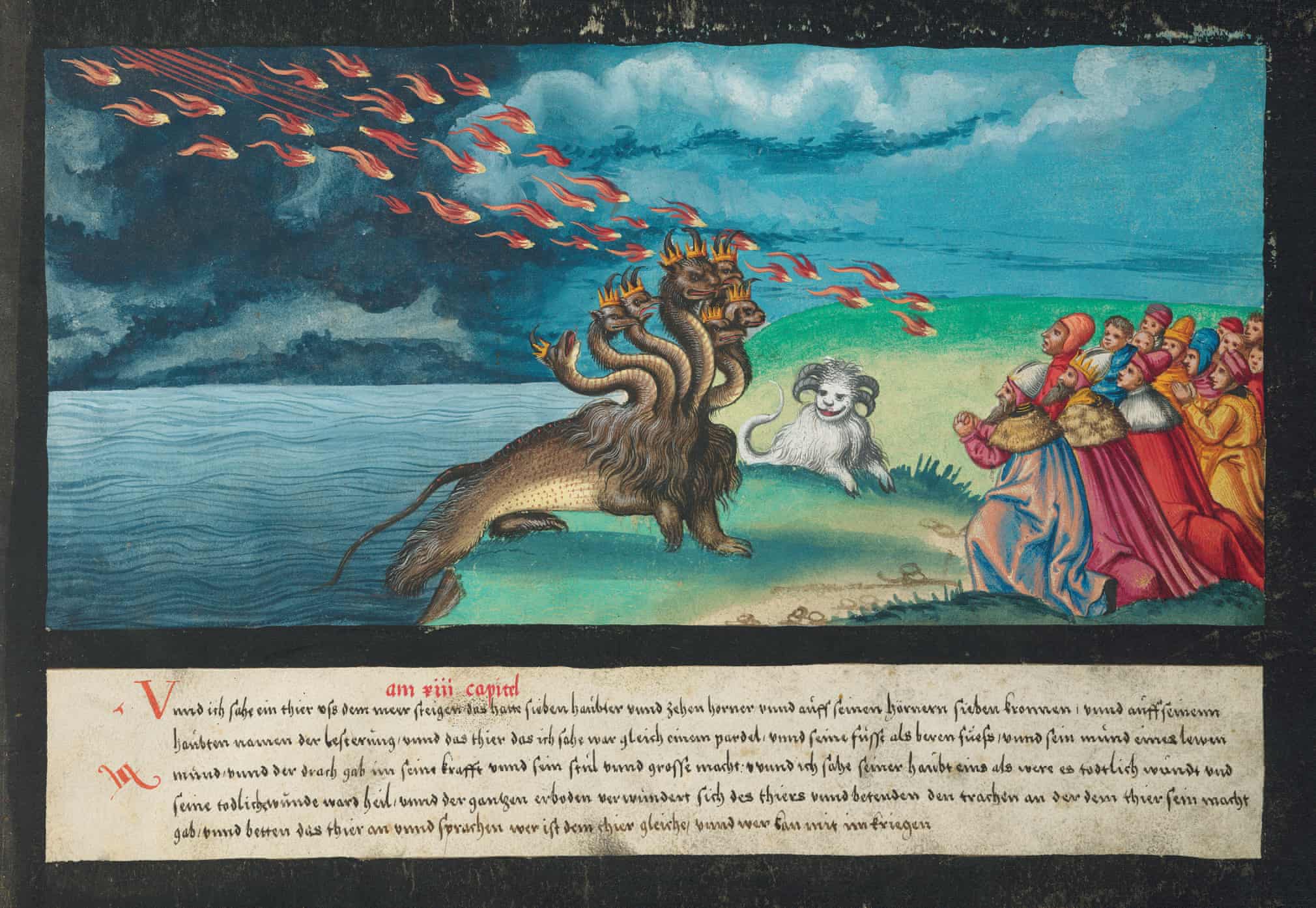

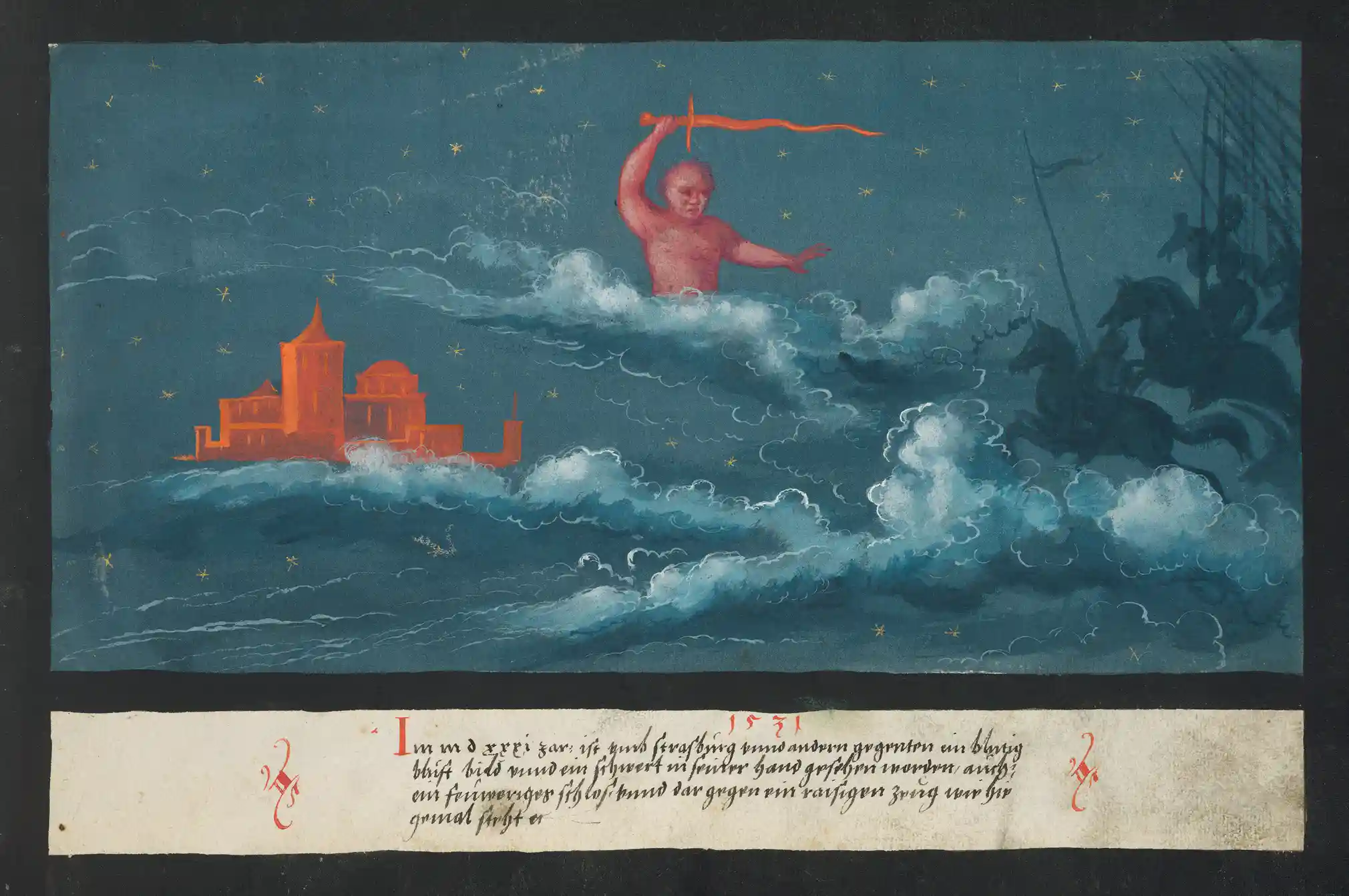

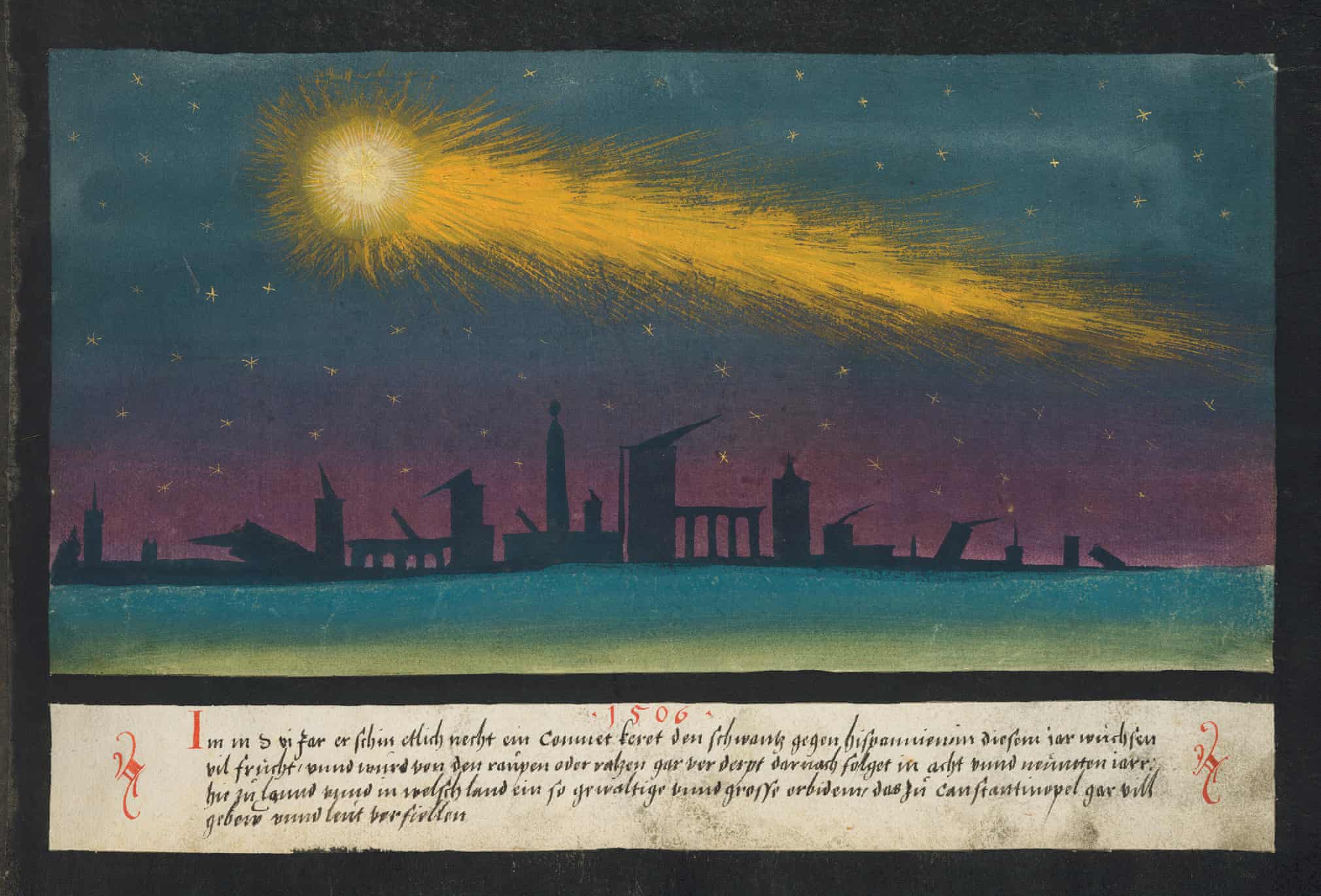

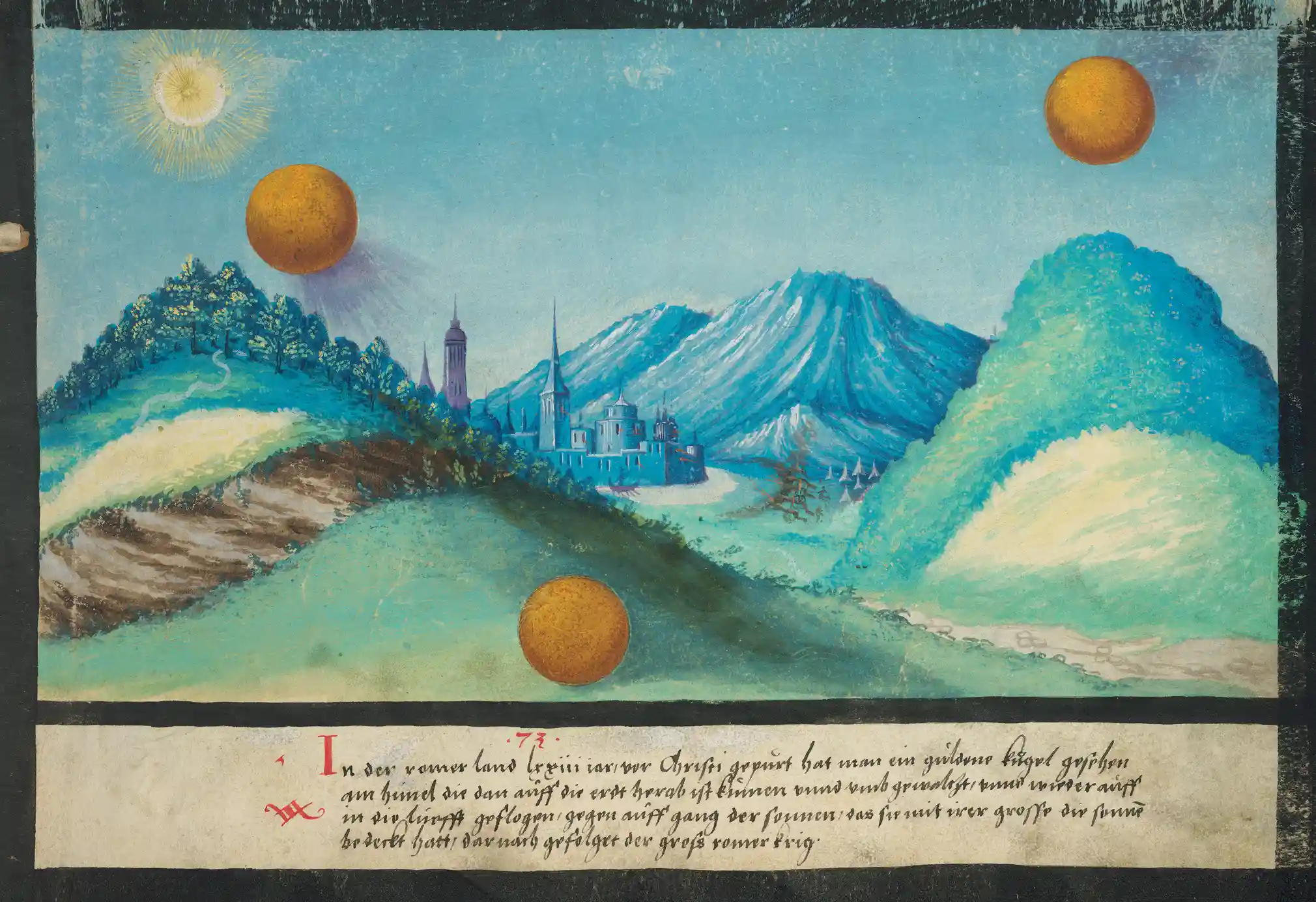

What passed through the mind of the illuminator of the manuscript shown here, the Augsburg Book of Miraculous Signs? We can never know. At best, scholars have settled on a name — artist and printmaker Hans Burgkmair the Younger — though little is known about him And we have a date, 1552, when this “curious and lavishly illustrated manuscript appeared in the Swabian Imperial Free city of Augsburg, then a part of the Holy Roman Empire, located in present-day Germany,” Maria Popova writes at the Marginalian. In the video at the top from Hochelaga, you can learn more about the “bizarre text” and the “meaning behind its unique contents” and “scenes of calamity and chaos.”

The strange book presents “in remarkable detail and wildly imaginative artwork, Medieval Europe’s growing obsessions with signs sent from ‘God,’ ” Popova writes, “a testament to the basic human propensity for magical thinking.” More specifically, The Book of Miracles recounts a host of Biblical signs and wonders in chronological order: from the first book of the Old Testament to the spectacular end of the New. In-between are “hallucinatory accounts of classical and contemporary celestial phenomena,” Tim Smith-Laing writes at Apollo. “The manuscript comprises nothing less than a picture chronicle of the world’s past, present and future, in 192 miracles.”

While Protestant Christianity condemned Medieval magic, “the recurrence of miracles in the Bible meant that the Protestant reformers of the sixteenth century could not reject such wonders as superstitions in the way they scorned Catholic beliefs,” Marina Warner writes at The New York Review of Books. German reformers were on high alert for the miraculous and ominous: “The sixteenth-century Zwinglian clergyman Johann Jakob Wick filled twenty-four albums with reports of such wonders in broadsheets and pamphlets,” seeing signs in the birth of a two-headed calf or “an unfortunate, flipper-handed infant.”

All of which is to say that we have little reason to doubt that the creator of The Book of Miracles meant the work as an earnest warning to its readers, although its wondrous images might look to us like proto-fantasy or sci-fi illustration. The book illustrates 1533 reports of flying dragons in Bohemia, an event, notes The Guardian, that “went on for several days, with over four hundred of them, both big and small, flying together.” It shows a comet appearing in 1506, one that stayed for several days and nights “and turned its tail towards Spain.” Thereby followed “a lot of fruit,” which was then “completely destroyed by caterpillars or rats,” then a violent earthquake in Constantinople.

The very tenuous connection between disparate natural phenomena, the hearsay reports of magical happenings, you can read about all of these signs and wonders in a republished version by Taschen, in English, French, and German. It is, Popova writes, “a singular shrine to some of the most eternal of human hopes and fears, and, above all, our immutable longing for grace, for mercy, for the miraculous.” See more images from The Book of Miracles at The Guardian.

Related Content:

A Digital Archive of Hieronymus Bosch’s Complete Works: Zoom In & Explore His Surreal Art

The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Has Been Digitized and Put Online

160,000+ Medieval Manuscripts Online: Where to Find Them

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...R.I.P. Vangelis: The Composer Who Created the Future Noir Soundtrack for Blade Runner Dies at 79

It would be difficult to overstate the prominence, in the late twentieth century, of the theme from Hugh Hudson’s Chariots of Fire. Most anyone under the age of 60 will have heard it many times as parody before ever seeing it in its original, Academy Award-winning context. Unfortunately, encountering the piece in nearly every humorous slow-motion running scene for two or three decades straight has a way of dampening its impact. But back in 1981, to score a nineteen-twenties period drama with brand-new digital synthesizers marked a brazen departure from convention, as well as the beginning of a trend of musical anachronism in cinema (which would manifest even in the likes of Dirty Dancing).

The Chariots of Fire theme has surely returned to many of our playlists after the death this week of its composer, Vangelis. Even before that film, he’d collaborated with Hudson on documentaries and commercials; immediately thereafter, he found himself in great demand as a composer for features.

The very next year, in fact, saw Vangelis crafting a score that has, perhaps, remained even more respected over time than the one he did for Chariots of Fire. Set in the far-flung year of 2019, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner needed a high-tech sound that also reflected its “future noir” sensibility. This neatly suited Vangelis’ proven ability to combine cutting-edge electronic instruments with traditional acoustic ones in a highly evocative fashion.

Blade Runner’s formidable influence owes primarily to its visuals, to the “look and feel” of its imagined future. But I defy fans of the film to remember any of its most striking images — the infernal skyline of 2019 Los Angeles, the cars flying between video-illuminated skyscrapers, Deckard’s first meeting with Rachael — without also hearing Vangelis’ music in their heads. Though it took audiences decades to catch up with Blade Runner, it’s now more or less settled that each element of the film complements all the others in creating a dystopian vision still, in many ways, unsurpassable. Vangelis’ own experiences across genres and technologies, which you can learn more about in the documentary Vangelis and the Journey to Ithaka, placed him ideally to imbue that vision with musical life.

Related content:

How Blade Runner Captured the Imagination of a Generation of Electronic Musicians

Stream 72 Hours of Ambient Sounds from Blade Runner: Relax, Go to Sleep in a Dystopian Future

Sean Connery (RIP) Reads C.P. Cavafy’s Epic Poem “Ithaca,” Set to the Music of Vangelis

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...Meet the Variophone, the Early Soviet Synthesizer that Made Music with a Film Projector (1932)

The early days of electronic instruments lacked commonly accepted ideas about what an electronic instrument was, much less how it should be used. No one associated electronics with techno or new wave or hip hop or pop, given that none of these existed. Every sound made by experiments in synthesis in the early 20th century was by its nature experimental, and most electronic instruments were one of a kind. It did not even seem obvious that electronic instruments had to be machines that were purpose built for sound.

In 1930, at the very dawn of sound on film, Evgeny Sholpo invented the Variophone — or “Automated Paper Sound with soundtracks in both transversal and intensive form.” It was, in simpler terms, a photoelectric audio synthesizer that made use of a film projector and spinning cardboard discs with sound waves cut into them in various patterns. When amplified, the device could turn the patterns into sounds. It also created “abstract spiral animation,” notes Boing Boing. Both “were way ahead of their time.”

If you’re thinking such a machine might be used to make film soundtracks, it was. But it was also “a continuation of research that Sholpo had been conducting since the 1910s,” the blog Beyond the Coda writes, “when he was working on performerless music.”

Sholpo wanted a device that would replace musicians and allow composers to turn complex musical ideas into recorded sounds themselves. He was aided in the endeavor by Georgy Rimsky-Korsakov (grandson of Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov), who helped him build the prototype at Lenfilm Studios in 1931.

The two produced their first film soundtrack for the propaganda film The Year 1905 in Bourgeoisie Satire, in 1931, and then the following year created “a synthesized soundtrack for A Symphony of Peace and many other soundtracks for films and cartoons throughout the thirties,” notes 120 Years of Electronic Music. The Variophone was destroyed during the Siege of Leningrad, but Sholpo built two more, continuing to record soundtracks through the forties. Unlike the first monophonic analogue synthesizers built a couple of decades later, the Variophone could create and replicate polyphonic compositions, since tones could be layered atop each other, as in multitrack recording.

You can hear several examples of the Variophone here, and see it synched to animation — both from its own sound waves and from hand-drawn films like “The Dance of the Crow,” below. What does it sound like? The tones and timbres vary somewhat among recordings. There’s clearly been some degradation in quality over time, and the technology of recording sound on film was only in its infancy at the time, in any case. But, in certain moments, the Variophone can sound like the early Moog that Wendy Carlos used to synthesize classical music and record film scores almost 40 years after Sholpo patented his machine.

via Boing Boing

Related Content:

How an 18th-Century Monk Invented the First Electronic Instrument

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Hans Zimmer Was in the First-Ever Video Aired on MTV, The Buggles’ “Video Killed the Radio Star”

More than four decades after its release, The Buggles’ “Video Killed the Radio Star” is usually credited with more pop-cultural importance than musical influence. Perhaps that befits the song whose video was the first-ever aired on MTV. But if you listen closely to the song itself in The Buggles’ recording (as opposed to the concurrently produced version by Bruce Woolley and the Camera Club, which also has its champions), you’ll hear an unexpected degree of both compositional and instrumental complexity. You’ll also have a sense of a fairly wide variety of inspirations, one that Buggles co-founder Trevor Horn has since described as including not just other music but literature as well.

“I’d read J. G. Ballard and had this vision of the future where record companies would have computers in the basement and manufacture artists,” said Horn in a 2018 Guardian interview. “I’d heard Kraftwerk’s The Man-Machine and video was coming. You could feel things changing.” The Buggles, Horn and collaborator Geoff Downes employed all the technology they could marshal. And by his reckoning, “Video Killed the Radio Star” would take 26 players to re-create live. Paying proper homage to Kraftwerk requires not just using machinery, but getting at least a little Teutonic; hence, perhaps, the brief appearance of Hans Zimmer at 2:50 in the song’s video.

“‘Hey, I like this idea of combining visuals and music,” Zimmer recently recalled having thought at the time. “This is going to be where I want to go.” And so he did: today, of course, we know Zimmer as perhaps the most famous film composer alive, sought after by some of the preeminent filmmakers of our time. He and Horn would actually collaborate again in the early nineteen-nineties on the soundtrack to Barry Levinson’s Toys (whose other contributors included no less an eighties video icon than Thomas Dolby, who’d played keyboards on the Bruce Woolley “Video Killed the Radio Star”). By that time Horn had put performing behind him and turned super-producer for artists like Yes, Seal, and the Pet Shop Boys. The Buggles burnt out quickly, but one doubts that Horn or Zimmer lose much sleep over it today.

Related content:

Watch the First Two Hours of MTV’s Inaugural Broadcast (August 1, 1981)

How Hans Zimmer Created the Otherworldly Soundtrack for Dune

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...The Animated Map of Quantum Computing: A Visual Introduction to the Future of Computing

If you listen to the hype surrounding quantum computing, you might think the near future shown in Alex Garland’s sci-fi series Devs is upon us — that we have computers complex enough to recreate time and space and reconstruct the human mind. Far from it. At this still-early stage, quantum computers promise much more than they can deliver, but the technology is “poised,” writes IBM “to transform the way you work in research.” The company does have — as do most other other big makers of what are now called “classical computers” — a “roadmap” for implementing quantum computing and a lot of cool new technology (such as the quantum runtime environment Quiskit) built around the qubit, the quantum computer version of the classical bit.

The computer bit, as we know, is a binary entity: either 1 or 0 and nothing in-between. The qubit, on the other hand, mimics quantum phenomena by remaining in a state of superposition of all possible states between 1 and 0 until users interact with it, like a spinning coin that only lands on one face if it’s physically engaged. And like quantum particles, qubits can become entangled with each other. Thus, “Quantum computers work exceptionally well for modeling other quantum systems,” writes Microsoft, “because they use quantum phenomena in their computation.” The possibilities are thrilling, and a little unsettling, but no one’s modeling the universe, or even a part of it, just quite yet.

“Use cases are largely experimental and hypothetical at this early stage,” McKinsey Digital writes in a report for businesses, while also noting that usable quantum systems may be on the market as early as 2030. If the roadmaps serve, that’s just around the corner, especially given how quickly quantum computers have evolved in relation to their (exponentially slower) classical forebears. “From the first idea of a quantum computer in 1980 [an idea attributed to Nobel prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman] to today, there has been a huge growth in the quantum computing industry, especially in the last ten years,” says Dominic Walliman in the video above, “with dozens of companies and startups spending hundreds of millions of dollars in a race to build the world’s best quantum computers.”

Walliman offers not only a (non-hyped) map of the possible future, but also a map of quantum computing’s past. He promises to clear up misconceptions we might have about the “different kinds of quantum computing, how they work, and why so many people are investing in the quantum computing industry.” We’ve previously seen Walliman’s Domain of Science channel do the same for such huge fields of scientific study as physics, chemistry, math, and classical computer science. Here, he presents cutting-edge science on the cusp of realization, explaining three essential ideas — superposition, entanglement, and interference — that govern quantum computing. The primary difference between quantum and classical computing from the point of view of non-specialists is algorithmic speed: while classical computers could theoretically perform the same complex functions as their quantum cousins, they would take ages to do so, or would halt and fizzle out in the attempt.

Will quantum computers be able to simulate nature down to the subatomic level in the future? McKinsey cautions, “experts are still debating the most foundational topics for the field.” Despite the industry’s rapid growth, “it’s not yet clear,” Walliman says, “which approach” among the many he surveys “will win out in the long run.” But if the roadmaps serve, we may not have to wait long to find out.

Related Content:

The Map of Physics: Animation Shows How All the Different Fields in Physics Fit Together

The Map of Chemistry: New Animation Summarizes the Entire Field of Chemistry in 12 Minutes

The Map of Mathematics: Animation Shows How All the Different Fields in Math Fit Together

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...How Hans Zimmer Created the Otherworldly Soundtrack for Dune

Many emotional moments were made at this year’s big awards shows. The Slap, amidst so many historic wins; poignant tributes and criminal omissions; former actor-turned-wartime-hero-president Volodymyr Zelensky’s speech, the return of Louis C.K…. Everybody’s got a lot to process. Pop culture can feel like a St. Vitus dance. One half-expects celebrities to start dropping from exhaustion. But then there’s Hans Zimmer’s Oscar acceptance speech, delivered in a white terry bathrobe, a miniature Oscar statuette in his pocket, a big goofy, 2 a.m. grin on his face. The man could not have looked more relaxed, winning his second Oscar 30 years after The Lion King.

Was he still in lockdown? No. On the night in question, Zimmer was in a hotel in Amsterdam, on tour with his band. “His category was among the eight that were handed out before the televised broadcast began,” Yahoo reports, “but he made sure his fans knew just how thrilled he was.” Zimmer posted a mini-acceptance speech to social media. “Who else has pajamas like this?” he joked to the other musicians gathered in the room. “Actually, let me say this, and this is for real. Had it not been for you, most of the people in this room, this would never have happened.” He is, as he says, “for real.”

As the musicians who worked with Zimmer on his Oscar-winning Dune soundtrack (stream it here) have gone on the record to say, the process was highly collaborative. “He’ll outline the desired end result rather than prescribing a specific means of getting there,” guitarist Guthrie Govan told The New York Times. “For one cue, he just said, ‘This needs to sound like sand.’ ” Zimmer’s methods offer new ways out of the cul-de-sac much of the creative industry seems to find itself in, repeating the same unhealthy compulsions. “If someone has a great idea,” he says, “I’m the first one to say, yes. Let’s go on that adventure.”

Along with collaboration, there is vision, and the willingness–as Zimmer says in Vanity Fair video interview at the top–to “invent instruments that don’t exist. Invent sounds that don’t exist.” Such future-thinking has always characterized his approach, from his synth pop and new wave work in the late 70s, including a stint killing the radio star with the Buggles, to his groundbreaking film composition work on Rain Man, The Thin Red Line, and the gritty blockbusters of Christopher Nolan. Though he’s scored action and adventure films unlikely to ever be considered art, Zimmer’s own way of working is thoroughly avant-garde.

As he tells it above, the point, in composing for Dune, was to throw out the science fiction boilerplate, the “orchestral sounds, romantic period tonalities” that have dominated at least since Kubrick’s 2001. On the other hand, Zimmer says, he wanted to get rid of modern syncopation. “Maybe in the future, we will not have regular beats. Maybe we will have actually progressed as human beings that we don’t need disco beats to enjoy ourselves,” he says laughing, before going on to demonstrate how he and his collaborators created some of the most original music in film history. Of course, the disco beat is comforting because it mimics the human heart. In making his Dune score, Zimmer was composing for a kind of post-human future, one dominated not by award-show drama but by giant sandworms.

Related Content:

Hear Hans Zimmer’s Experimental Score for the New Dune Film

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...The Forgotten Women of Surrealism: A Magical, Short Animated Film

“The problem of woman is the most marvelous and disturbing problem in all the world,” — Andre Breton, 1929 Surrealist Manifesto.

“I warn you, I refuse to be an object.” — Leonora Carrington

Fashion model, writer, and photographer Lee Miller had many lives. Discovered by Condé Nast in New York (when he pulled her out of the path of traffic), she became a famous face of Vogue in the 1920s, then launched her own photographic career, for which she has been justly celebrated: both for her work in the fashion world and on the battlefields (and Hitler’s tub!) in World War II. One of Miller’s achievements often gets left out in mentions of her life, the Surrealist work she created as an artist in the 1930s.

Hailed as a “legendary beauty,” writes the National Galleries of Scotland, Miller studied acting, dance, and experimental theater. “She learned photography first through being a subject for the most important fashion photographers of her day, including Nickolas Muray, Arnold Genthe and Edward Steichen.” Her apprenticeship and affair with Man Ray is, of course, well-known. But rather than calling Miller an active participant in his art and her own (she co-created the “solarization” process he used, for example) she’s mostly referred to only as his muse, lover, and favorite subject.

“Surrealism had a very high proportion of women members who were at the heart of the movement, but who often get cast as ‘muse of’ or ‘wife of,’ ” says Susanna Greeves, curator of an all-women Surrealist exhibit in South London. The marginalization of women Surrealists is not a historical oversight, many critics and scholars contend, but a central feature of the movement itself. When British Surrealist Eileen Agar said in a 1990 interview, “In those days, men thought of women simply as muses,” she was too polite by half.

Despite their radical politics, male Surrealists perfected turning women into disfigured objects. “While Dalí used the female figure in optical puzzles, Magritte painted pornified faces with breasts for eyes, and Ernst simply decapitated them,” Izabella Scott writes at Artsy. Surrealist artist René Crevel wrote in 1934, “the Noble Mannequin is so perfect. She does not always bother to take her head, arms and legs with her.” Edgar Allan Poe’s love for “beautiful dead girls” escalated into dismemberment.

Dalí employed no lyrical obfuscation in his thoughts on the place of women in the movement. He called his contemporary, Argentine/Italian artist Leonor Fini (who never considered herself a Surrealist), “better than most, perhaps.” Then he felt compelled to add, “but talent is in the balls.”

When writing her dissertation on Surrealism in the 1970s at New York University, Gloria Feman Orenstein found that all of the women had been totally left out of the record. So she found them — tracking down and becoming “a close friend to many influential female surrealists,” notes Aeon, “including Leonora Carrington and Meret Elisabeth Oppeneim” (another Man Ray model and the only Surrealist of any gender to have actual training and experience in psychoanalysis).

Through her research, Orenstein “became the academic voice of feminist surrealism,” recovering the work of artists who had always been part of the movement, but who had been shouldered aside by male contemporaries, lovers, and husbands who did not see them on equal terms. In the short film above, Gloria’s Call, L.A.-based artist Cheri Gaulke “manifests Orenstein’s journey into the surreal with collage-like animations.” It was a quest that took her around the world, from Paris to Samiland, and it began in Mexico City, where she met the great Leonora Carrington.

See how Orenstein not only rediscovered the women of Surrealism, but helped recover the essential roots of Surrealism in Latin America, also erased by the art historical scholarship of her time. And learn more about the artists she befriended and brought to light at Artspace and in Penelope Rosemont’s 1998 book, Surrealist Women: An International Anthology.

Related Content:

An Introduction to Surrealism: The Big Aesthetic Ideas Presented in Three Videos

David Lynch Presents the History of Surrealist Film (1987)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Real Interviews with People Who Lived in the 1800s

The nineteenth century is well and truly gone. That may sound like a trivial claim, given that we’re now living in the 2020s, but only in recent years did we lose the last person born in that time. With Tajima Nabi, a Japanese woman who died in 2018 at the age of 117 years, went our last living connection to the nineteenth century (1900, the year of Tajima’s birth, technically being that century’s last year.) Luckily that same century saw the invention of photography, sound recording, and even motion pictures, which offered certain of its inhabitants a means of preserving not just their memories but their manner. You can view a collection of just such footage, restored and colorized, at the Youtube channel Life in the 1800s.

In the channel’s playlist of interview clips you’ll find first-hand memories of, if not the particular decade of the eighteen-hundreds, then at least of the eighteen-fifties through the eighteen-nineties. Take the inventor Elihu Thomson, interview subject in the video at the top of the post. Born in England in 1853, Thomson emigrated with his family to the United States in 1857.

They settled in Philadelphia, where Thomson found himself “forced out of school at eleven” because he wasn’t yet old enough to enter high school. Some advisors said, “Keep him away from books and let him develop physically.” To which the young Thompson responded, “If you do that, you might as well kill me now, because I’ve got to have my books.”

One of those books was full of “chemistry experiments and electrical experiments,” and carrying them out himself gave Thomson his “first knowledge of electricity” — a phenomenon of great importance to the development that would happen throughout the rest of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Albert L. Salt also got in on the ground floor, having started working for Western Electric at age fourteen in 1881 and eventually become the president of Western Electric’s appliance subsidiary Graybar. But of course, not everyone had such a professional ladder available: take the elderly interviewees in the footage just above, who were born into slavery the eighteen-forties and eighteen-fifties.

The more distant a time grows, the more it tends to flatten in our perception. In the absence of deliberate historical research, we lack a sense of the various texture of eras out of living memory. In the United States of America alone, the nineteenth century encompassed both great technological innovation and the days of the Wild West. The latter was the realm known to Civil War veteran and photographer William Henry Jackson, who in the interview above remembers the American west “before the cowboys came in” — not the time of the cowboys, but before. Could Florence Pannell, whose memories of Victorian England we previously featured here on Open Culture, have imagined his world? Could he have imagined hers? See more interviews here.

Related content:

A 108-Year-Old Woman Recalls What It Was Like to Be a Woman in Victorian England

What the First Movies Really Looked Like: Discover the IMAX Films of the 1890s

A Rare Smile Captured in a 19th Century Photograph

Hand-Colored Photographs of 19th Century Japan

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...