Sci-Fi Writer Arthur C. Clarke Predicts the Future in 1964: Artificial Intelligence, Instantaneous Global Communication, Remote Work, Singularity & More

Are you feeling confident about the future? No? We understand. Would you like to know what it was like to feel a deep certainty that the decades to come were going to be filled with wonder and the fantastic? Well then, gaze upon this clip from the BBC Archive YouTube channel of sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke predicting the future in 1964.

Although we best know him for writing 2001: A Space Odyssey, the 1964 television viewing public would have known him for his futurism and his talent for calmly explaining all the great things to come. In the late 1940s, he had already predicted telecommunication satellites. In 1962 he published his collected essays, Profiles of the Future, which contains many of the ideas in this clip.

Here he correctly predicts the ease with which we can be contacted wherever in the world we choose to, where we can contact our friends “anywhere on earth even if we don’t know their location.” What Clarke doesn’t predict here is how “location” isn’t a thing when we’re on the internet. He imagines people working just as well from Tahiti or Bali as they do from London. Clarke sees this advancement as the downfall of the modern city, as we do not need to commute into the city to work. Now, as so many of us are doing our jobs from home post-COVID, we’ve also discovered the dystopia in that fantasy. (It certainly hasn’t dropped the cost of rent.)

Next, he predicts advances in biotechnology that would allow us to, say, train monkeys to work as servants and workers. (Until, he jokes, they form a union and “we’d be back right where we started.) Perhaps, he says, humans have stopped evolving—what comes next is artificial intelligence (although that phrase had yet to be used) and machine evolution, where we’d be honored to be the “stepping stone” towards that destiny. Make of that what you will. I know you might think it would be cool to have a monkey butler, but c’mon, think of the ethics, not to mention the cost of bananas.

Pointing out where Clarke gets it wrong is too easy—-nobody gets it right all of the time. However, it is fascinating that some things that have never come to pass—-being able to learn a language overnight, or erasing your memories—have managed to resurface over the years as fiction films, like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. His ideas of cryogenic suspension are staples of numerous hard sci-fi films.

And we are still waiting for the “Replicator” machine, which would make exact duplicates of objects (and by so doing cause a collapse into “gluttonous barbarism” because we’d want unlimited amounts of everything.) Some commenters call this a precursor to 3‑D printing. I’d say otherwise, but something very close to it might be around the corner. Who knows? Clarke himself agrees about all this conjecture-—it’s doomed to fail.

“That is why the future is so endlessly fascinating. Try as we can, we’ll never outguess it.”

Related Content:

Hear Arthur C. Clarke Read 2001: A Space Odyssey: A Vintage 1976 Vinyl Recording

Isaac Asimov Predicts the Future on The David Letterman Show (1980)

Octavia Butler’s Four Rules for Predicting the Future

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

Read More...An Introduction to the Voynich Manuscript, the World’s Most Mysterious Book

“The Voynich manuscript is a real medieval book, and has been carbon-dated to the early 1400s.” No modern hoax, this notoriously bizarre text has in fact “passed through the hands of many over the years,” including “scientists, emperors, and collectors.” Though “we still don’t know who actually wrote it, the illustrations hint at the book’s original purpose,” having “much in common with medieval herbals, astrology guides, and bathing manuals.” Hence the likelihood of the Voynich manuscript being “some sort of medical textbook, although a very strange one by any measure. Then there’s the writing.”

This summary of the known history and nature of the most mysterious manuscript in existence comes from the Youtube video above, “Secrets of the Voynich Manuscript.” Its channel Hochelaga has previously been featured here on Open Culture for episodes on medieval monsters, a guide to supernatural phenomena from renaissance Germany, Hokusai’s ghost art, and the Biblical apocalypse.

In short, the Voynich manuscript could hardly find a more accommodating wheelhouse. And as in Hochelaga’s other videos, the subject is approached not with total credulity, but rather a clear and straightforward discussion of why generation after generation of enthusiasts have kept trying to figure it out.

No aspect of the Voynich manuscript fascinates as much as its having been “written in a mystery language with a unique alphabet and grammatical rules.” It could be an existing language rendered in code; it could be one created entirely and only for this book. Though attempts are made with some frequency, “no one has been able to definitively solve the Voynich manuscript’s language.” It could, of course, be that “we’ve fallen for one big medieval prank,” but the video’s creator doesn’t buy that explanation. Even in its incomprehensibility, the text appears to possess great complexity. If it were to be decoded, “would the magic and mystery disappear? Or would we uncover a whole new set of questions and embark on another journey entirely?”

Related content:

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...Take Graphic Design Courses to Launch Your Career as a Graphic Designer, Video Game Designer, UI Designer & More

What can you do with graphic design skills? More and more, it seems, as emerging technologies drive new apps, software, and games. New design challenges are everywhere, from human-machine interfaces, to 3D modeling in video games and animated films, to re-imagining classic designs in print and on screen. In addition to traditional jobs like art director, graphic designer, production artist, and animator, the past few years have seen a sharp rise in demand for User Experience (UX) and User Interface (UI) designers, roles that require a variety of different creative and technical skill sets.

You could get a four-year degree in design to work in one of these fields, or you could take a Coursera Specialization and be one step closer. Coursera has met the demand for new job skills and tech education by partnering with top arts institutions and universities to offer online courses at low cost. All of these courses grant certificates that show potential employers you’re ready to put your learning to use. If careers in art and contemporary design, graphic design, web user experience and interface design, or video game design appeal to you, you can learn those skills in the five certificate-granting Specialization programs below.

- Graphic Design Specialization (5 courses offered by California Institute of the Arts)

- UI / UX Design Specialization (4 courses offered by California Institute of the Arts)

- Modern and Contemporary Art and Design Specialization (4 courses Museum of Modern Art)

- Game Design: Art and Concepts Specialization (4 courses offered by California Institute of the Arts)

- Graphic Design Elements for Non-Designers Specialization (4 courses offered by University of Colorado Boulder)

Graphic designers can choose to be as specialized or generalized as they like, but as in all creative fields, they need a thorough understanding of the basics. A Coursera Specialization is a series of courses intended to lead students to mastery, building on the history and foundations of the field. You can enroll for free and try out any of the Specializations for 7 days. After that, you’ll be charged between $39-$49 per month until you complete the courses in a Specialization. (Financial aid is available).

The exciting Specializations from CALARTS and the Museum of Modern Art will bring you many steps closer to a new career, or maybe even a new personal passion project.

Note: Open Culture has a partnership with Coursera. If readers enroll in certain Coursera courses and programs, it helps support Open Culture.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Aldous Huxley to George Orwell: My Hellish Vision of the Future is Better Than Yours (1949)

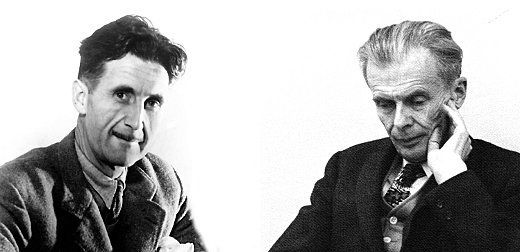

In 1949, George Orwell received a curious letter from his former high school French teacher.

Orwell had just published his groundbreaking book Nineteen Eighty-Four, which received glowing reviews from just about every corner of the English-speaking world. His French teacher, as it happens, was none other than Aldous Huxley who taught at Eton for a spell before writing Brave New World (1931), the other great 20th century dystopian novel.

Huxley starts off the letter praising the book, describing it as “profoundly important.” He continues, “The philosophy of the ruling minority in Nineteen Eighty-Four is a sadism which has been carried to its logical conclusion by going beyond sex and denying it.”

Then Huxley switches gears and criticizes the book, writing, “Whether in actual fact the policy of the boot-on-the-face can go on indefinitely seems doubtful. My own belief is that the ruling oligarchy will find less arduous and wasteful ways of governing and of satisfying its lust for power, and these ways will resemble those which I described in Brave New World.” (Listen to him read a dramatized version of the book here.)

Basically while praising Nineteen Eighty-Four, Huxley argues that his version of the future was more likely to come to pass.

In Huxley’s seemingly dystopic World State, the elite amuse the masses into submission with a mind-numbing drug called Soma and an endless buffet of casual sex. Orwell’s Oceania, on the other hand, keeps the masses in check with fear thanks to an endless war and a hyper-competent surveillance state. At first blush, they might seem like they are diametrically opposed but, in fact, an Orwellian world and a Huxleyan one are simply two different modes of oppression.

Obviously we are nowhere near either dystopic vision but the power of both books is that they tap into our fears of the state. While Huxley might make you look askance at The Bachelor or Facebook, Orwell makes you recoil in horror at the government throwing around phrases like “enhanced interrogation” and “surgical drone strikes.”

You can read Huxley’s full letter below.

Wrightwood. Cal.

21 October, 1949

Dear Mr. Orwell,

It was very kind of you to tell your publishers to send me a copy of your book. It arrived as I was in the midst of a piece of work that required much reading and consulting of references; and since poor sight makes it necessary for me to ration my reading, I had to wait a long time before being able to embark on Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Agreeing with all that the critics have written of it, I need not tell you, yet once more, how fine and how profoundly important the book is. May I speak instead of the thing with which the book deals — the ultimate revolution? The first hints of a philosophy of the ultimate revolution — the revolution which lies beyond politics and economics, and which aims at total subversion of the individual’s psychology and physiology — are to be found in the Marquis de Sade, who regarded himself as the continuator, the consummator, of Robespierre and Babeuf. The philosophy of the ruling minority in Nineteen Eighty-Four is a sadism which has been carried to its logical conclusion by going beyond sex and denying it. Whether in actual fact the policy of the boot-on-the-face can go on indefinitely seems doubtful. My own belief is that the ruling oligarchy will find less arduous and wasteful ways of governing and of satisfying its lust for power, and these ways will resemble those which I described in Brave New World. I have had occasion recently to look into the history of animal magnetism and hypnotism, and have been greatly struck by the way in which, for a hundred and fifty years, the world has refused to take serious cognizance of the discoveries of Mesmer, Braid, Esdaile, and the rest.

Partly because of the prevailing materialism and partly because of prevailing respectability, nineteenth-century philosophers and men of science were not willing to investigate the odder facts of psychology for practical men, such as politicians, soldiers and policemen, to apply in the field of government. Thanks to the voluntary ignorance of our fathers, the advent of the ultimate revolution was delayed for five or six generations. Another lucky accident was Freud’s inability to hypnotize successfully and his consequent disparagement of hypnotism. This delayed the general application of hypnotism to psychiatry for at least forty years. But now psycho-analysis is being combined with hypnosis; and hypnosis has been made easy and indefinitely extensible through the use of barbiturates, which induce a hypnoid and suggestible state in even the most recalcitrant subjects.

Within the next generation I believe that the world’s rulers will discover that infant conditioning and narco-hypnosis are more efficient, as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into loving their servitude as by flogging and kicking them into obedience. In other words, I feel that the nightmare of Nineteen Eighty-Four is destined to modulate into the nightmare of a world having more resemblance to that which I imagined in Brave New World. The change will be brought about as a result of a felt need for increased efficiency. Meanwhile, of course, there may be a large scale biological and atomic war — in which case we shall have nightmares of other and scarcely imaginable kinds.

Thank you once again for the book.

Yours sincerely,

Aldous Huxley

Related Content:

A Complete Reading of George Orwell’s 1984: Aired on Pacifica Radio, 1975

George Orwell Explains in a Revealing 1944 Letter Why He’d Write 1984

Hear Aldous Huxley Narrate His Dystopian Masterpiece, Brave New World

Aldous Huxley’s Most Beautiful, LSD-Assisted Death: A Letter from His Widow

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.

Read More...An Introduction to Stanislaw Lem, the Great Polish Sci-Fi Writer, by Jonathan Lethem

Who was Stanislaw Lem? The Polish science fiction writer, novelist, essayist, and polymath may best be known for his 1961 novel Solaris (adapted for the screen by Andrei Tarkosvky in 1972 and again by Steven Soderbergh in 2014). Lem’s science fiction appealed broadly outside of SF fandom, attracting the likes of John Updike, who called his stories “marvelous” and Lem a poet of “scientific terminology” for readers “whose hearts beat faster when the Scientific American arrives each month.”

Updike’s characterization is but one version of Lem. There are several more, writes Jonathan Lethem in an essay for the London Review of Books, penned for Lem’s 100th anniversary – at least five different Lems with five different literary personalities. Only the first is a “hard science fiction writer,” the genre originating not with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, but “in H.G. Wells’ technological prognostications.”

Represented best in the pages of Astounding Stories and other sci-fi pulps, hard sci-fi “advertises consumer goods like personal robots and flying cars. It valorizes space travel that culminates in successful, if difficult, contact with the alien life assumed to be strewn throughout the galaxies.” The genre also became tied to “American exceptionalist ideology, technocratic triumphalism, manifest destiny” and “libertarian survivalist bullshit,” says Lethem.

Lem had no use for these attitudes. In his guise as a critic and reviewer he wrote, “the scientific ignorance of most American science-fiction writers was as inexplicable as the abominable literary quality of their output.” He admired the English H.G. Wells, comparing him to the inventor of chess, and American Philip K. Dick, whom he called a “visionary among charlatans.” But Lem hated most hard sci-fi, though he himself, says Lethem, was a hard sci-fi writer “with visionary gifts and inexhaustible diligence when it came to the task of extrapolation.”

Much of Lem’s work was of another kind, as Lethem explains in the short film above, a condensed version of his essay. The second Lem “wrote fairy tales and folk tales of the future.” The third, “wrote just two novels, yet he could easily be, on the right day, one’s favorite.” Lem number four “is the pure post-modernist, who unified his essayistic and fictional selves with a Borgesian or Nabokovian gesture.” This Lem, for example, wrote the very Borgesian A Perfect Vacuum: Perfect Reviews of Nonexistent Books.

Lem number five, says Lethem, is “another major figure,” this one a prolific literary essayist, critic, reviewer, and non-fiction writer whose breadth is staggering. Rather than confining him with the label “futurist,” Lethem calls him an “anythingist,” a point Lem proved with his 1964 Summa Technologiae, a “masterwork of non-fiction,” Simon Ings writes at New Scientist, with the ambition and scope of the 13th-century Aquinas work for which it’s named.

This fifth and final Lem “will be a fabulous shock to those who know only his science fiction,” writes Ings. Only translated into English in 2014, his Summa presages search engines, virtual reality, and technological singularity. It attempts an “all encompassing… discourse on evolution,” commented biophysicist Peter Butko, “not only… of science and technology… but also evolution of life, humanity, consciousness, culture, and civilization.”

The last Lem makes for heady reading, but he imbues this work with the same wit and wickedly satirical voice we find in the first four. He operated, after all, as Lethem writes in his essay celebrating the Polish author at 100, “in the spirit of other Iron Curtain figures who slipped below the censor’s radar by using forms regarded as unserious.” Yet few have taken the form of science fiction more seriously.

via Aeon

Related Content:

“Auteur in Space”: A Video Essay on How Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris Transcends Science Fiction

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: 17,500 Entries on All Things Sci-Fi Are Now Free Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Discover DALL‑E, the Artificial Intelligence Artist That Lets You Create Surreal Artwork

DALL‑E, an artificial intelligence system that generates viable-looking art in a variety of styles in response to user supplied text prompts, has been garnering a lot of interest since it debuted this spring.

It has yet to be released to the general public, but while we’re waiting, you could have a go at DALL‑E Mini, an open source AI model that generates a grid of images inspired by any phrase you care to type into its search box.

Co-creator Boris Dayma explains how DALL‑E Mini learns by viewing millions of captioned online images:

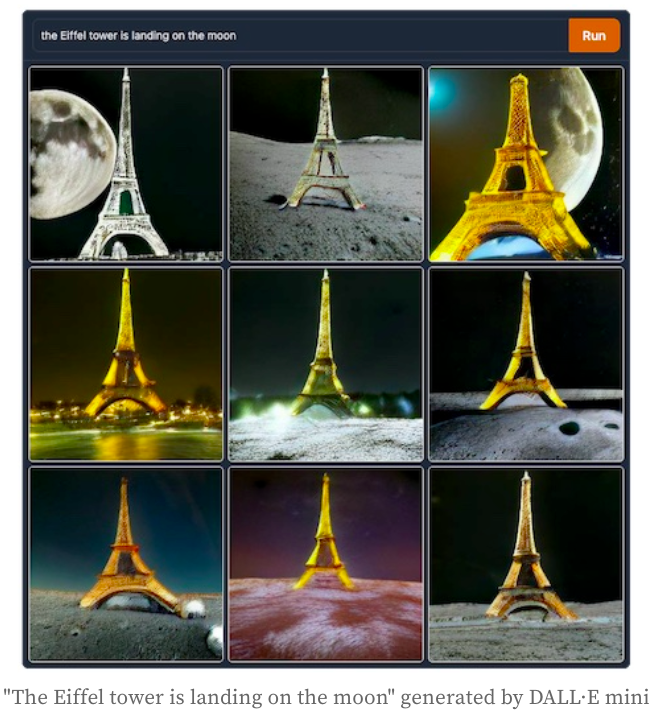

Some of the concepts are learnt (sic) from memory as it may have seen similar images. However, it can also learn how to create unique images that don’t exist such as “the Eiffel tower is landing on the moon” by combining multiple concepts together.

Several models are combined together to achieve these results:

• an image encoder that turns raw images into a sequence of numbers with its associated decoder

• a model that turns a text prompt into an encoded image

• a model that judges the quality of the images generated for better filtering

My first attempt to generate some art using DALL‑E mini failed to yield the hoped for weirdness. I blame the blandness of my search term — “tomato soup.”

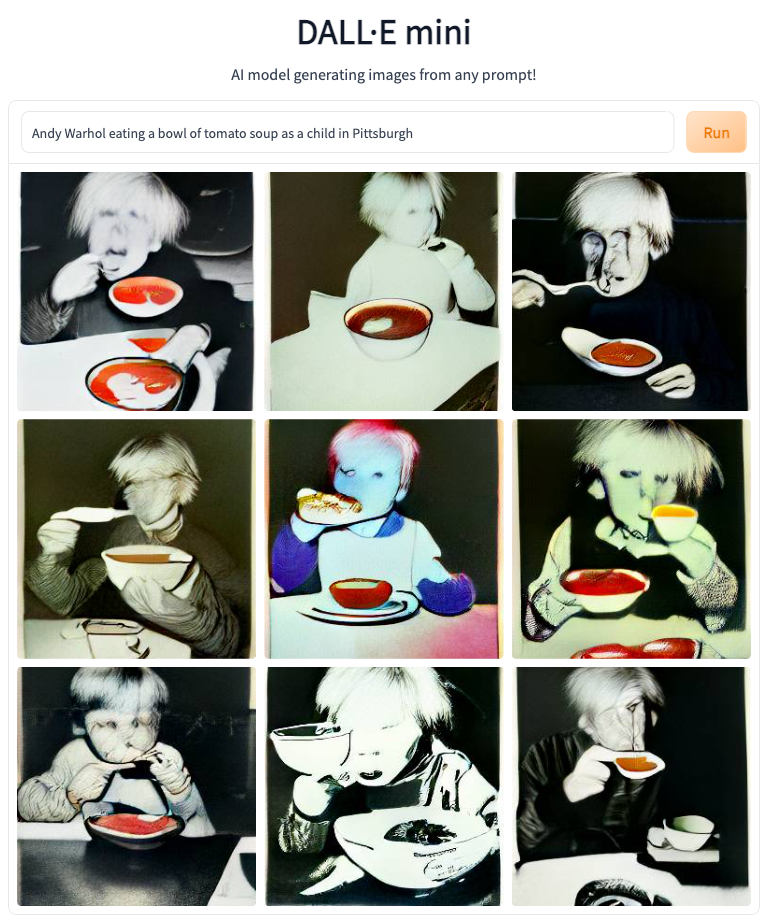

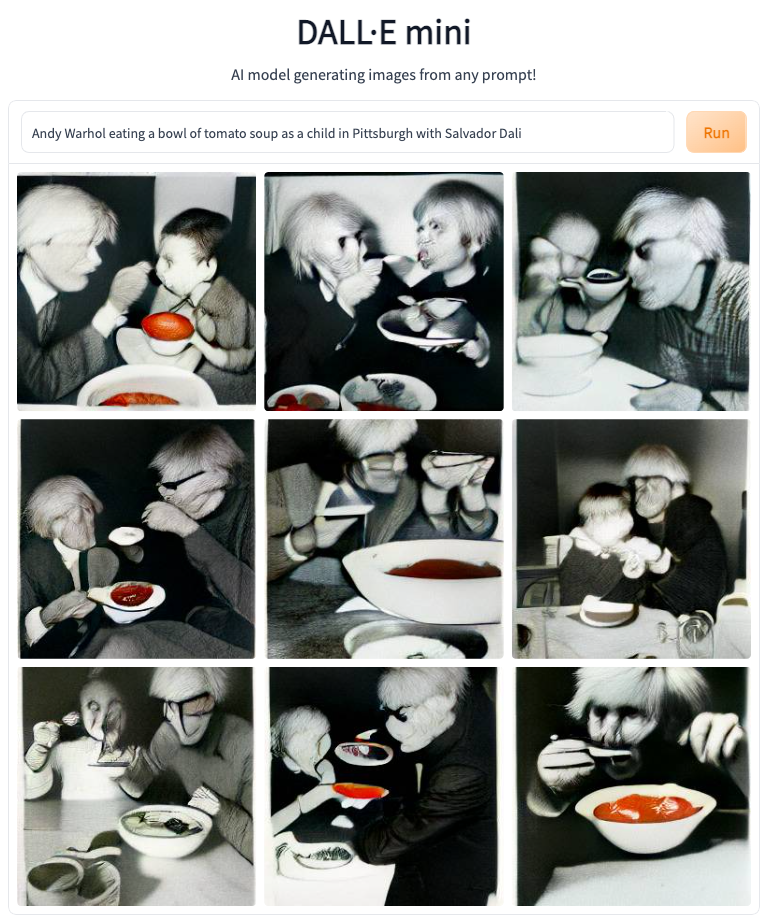

Perhaps I’d have better luck “Andy Warhol eating a bowl of tomato soup as a child in Pittsburgh.”

Ah, there we go!

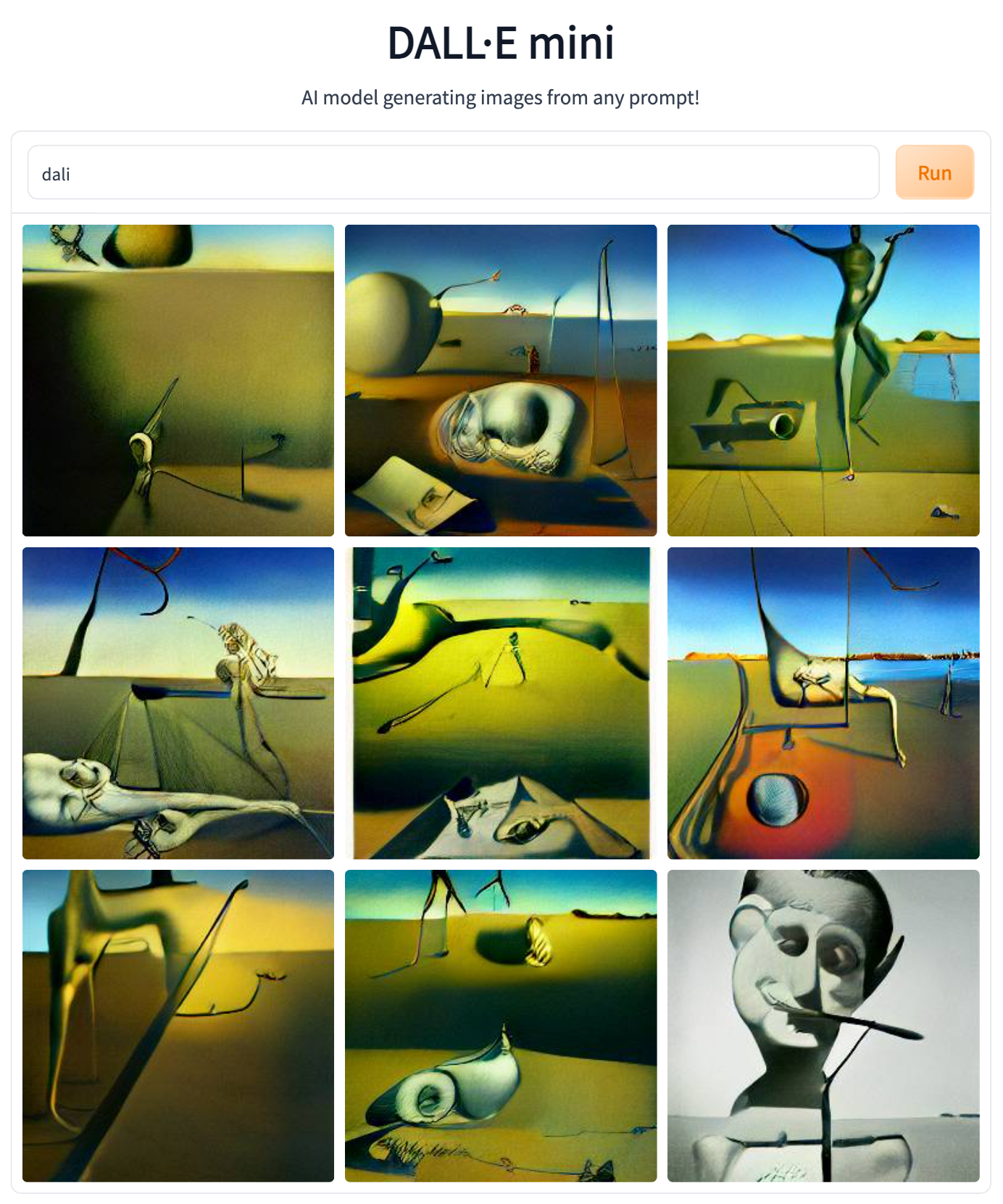

I was curious to know how DALL‑E Mini would riff on its namesake artist’s handle (an honor Dali shares with the titular AI hero of Pixar’s 2018 animated feature, WALL‑E.)

Hmm… seems like we’re backsliding a bit.

Let me try “Andy Warhol eating a bowl of tomato soup as a child in Pittsburgh with Salvador Dali.”

Ye gods! That’s the stuff of nightmares, but it also strikes me as pretty legit modern art. Love the sparing use of red. Well done, DALL‑E mini.

At this point, vanity got the better of me and I did the AI art-generating equivalent of googling my own name, adding “in a tutu” because who among us hasn’t dreamed of being a ballerina at some point?

Let that be a lesson to you, Pandora…

Hopefully we’re all planning to use this playful open AI tool for good, not evil.

Hyperallergic’s Sarah Rose Sharp raised some valid concerns in relation to the original, more sophisticated DALL‑E:

It’s all fun and games when you’re generating “robot playing chess” in the style of Matisse, but dropping machine-generated imagery on a public that seems less capable than ever of distinguishing fact from fiction feels like a dangerous trend.

Additionally, DALL‑E’s neural network can yield sexist and racist images, a recurring issue with AI technology. For instance, a reporter at Vice found that prompts including search terms like “CEO” exclusively generated images of White men in business attire. The company acknowledges that DALL‑E “inherits various biases from its training data, and its outputs sometimes reinforce societal stereotypes.”

Co-creator Dayma does not duck the troubling implications and biases his baby could unleash:

While the capabilities of image generation models are impressive, they may also reinforce or exacerbate societal biases. While the extent and nature of the biases of the DALL·E mini model have yet to be fully documented, given the fact that the model was trained on unfiltered data from the Internet, it may generate images that contain stereotypes against minority groups. Work to analyze the nature and extent of these limitations is ongoing, and will be documented in more detail in the DALL·E mini model card.

The New Yorker cartoonists Ellis Rosen and Jason Adam Katzenstein conjure another way in which DALL‑E mini could break with the social contract:

And a Twitter user who goes by St. Rev. Dr. Rev blows minds and opens multiple cans of worms, using panels from cartoonist Joshua Barkman’s beloved webcomic, False Knees:

Proceed with caution, and play around with DALL‑E mini here.

Get on the waitlist for original flavor DALL‑E access here.

Related Content

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Ziggy Stardust Turns 50: Celebrate David Bowie’s Signature Character with a Newly Released Version of “Starman”

David Bowie’s fans have now been enjoying the character of Ziggy Stardust for a full five decades. That’s hardly a bad run, given that the opening track of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars announces that the end of the world will come in just five years. Released on June 16th, 1972, that album gave the public its introduction to the title character, an androgynous rock star from a distant star who one day arrives, messiah-like, on the dying Earth. But as the musical story goes, the resulting fame proves too much for him: the hapless Ziggy ends up in shambles, victimized by Earthly desires in all their manifestations.

One could read into all this certain aspirations and fears on the part of Ziggy Stardust’s creator-performer, the young David Bowie. Broad critical consensus holds that it was on the previous year’s Hunky Dory that Bowie first showed his true artistic potential.

Though that album, his fourth, boasted signature-songs-to-be like “Changes” and “Life on Mars?”, Bowie declared (no doubt to the label’s frustration) that he wouldn’t bother promoting it, since he was just about to change his image. This turned out to be a shrewd move, since his subsequent transformation into Ziggy Stardust launched him out of the realm of the respected niche singer-songwriter and into the stratosphere of the bona fide rock star.

Why did Ziggy Stardust drive so many listeners to near-maniac appreciation half a century ago? In Bowie’s native England, many cite his July 1972 performance of “Starman” the BBC’s Top of the Pops as the turning point. Though only mildly psychedelic, the segment celebrated the colorfully askew glamour of Bowie-as-Ziggy and his band the Spiders from Mars just when it was desperately needed. As music critic Simon Reynolds writes, “It is hard to reconstruct the drabness, the visual depletion of Britain in 1972, which filtered into the music papers to form the grey and grubby backdrop to Bowie’s physical and sartorial splendor.” Today you can hear a newly released 2022 mix of “Starman” constructed from the tracks recorded for Top of the Pops those 50 years ago.

Imagine the impact on a young English pop-music fan in 1972 who happened to be watching on color (or rather, colour) television, itself introduced only a few years earlier. Though Bowie may have chosen just the right historical moment to debut the first of his musical personae, he didn’t create Ziggy Stardust ex nihilo. Elements of the character have clear precedents earlier in Bowie’s career, not least in the promotional film for 1968’s “Space Oddity,” the 2001-inspired single that first associated him with the realms beyond our planet. But Ziggy was Bowie’s first genuine alter ego, a character perfectly suited to the era of “glam rock” who could conveniently be retired when that era passed. Glam rock may be long gone, but Ziggy Stardust still looks and sounds as if he’d only just landed on Earth.

Related content:

David Bowie Recalls the Strange Experience of Inventing the Character Ziggy Stardust (1977)

The Story of Ziggy Stardust: How David Bowie Created the Character that Made Him Famous

David Bowie Became Ziggy Stardust 48 Years Ago This Week: Watch Original Footage

Hear Demo Recordings of David Bowie’s “Ziggy Stardust,” “Space Oddity” & “Changes”

David Bowie Remembers His Ziggy Stardust Days in Animated Video

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

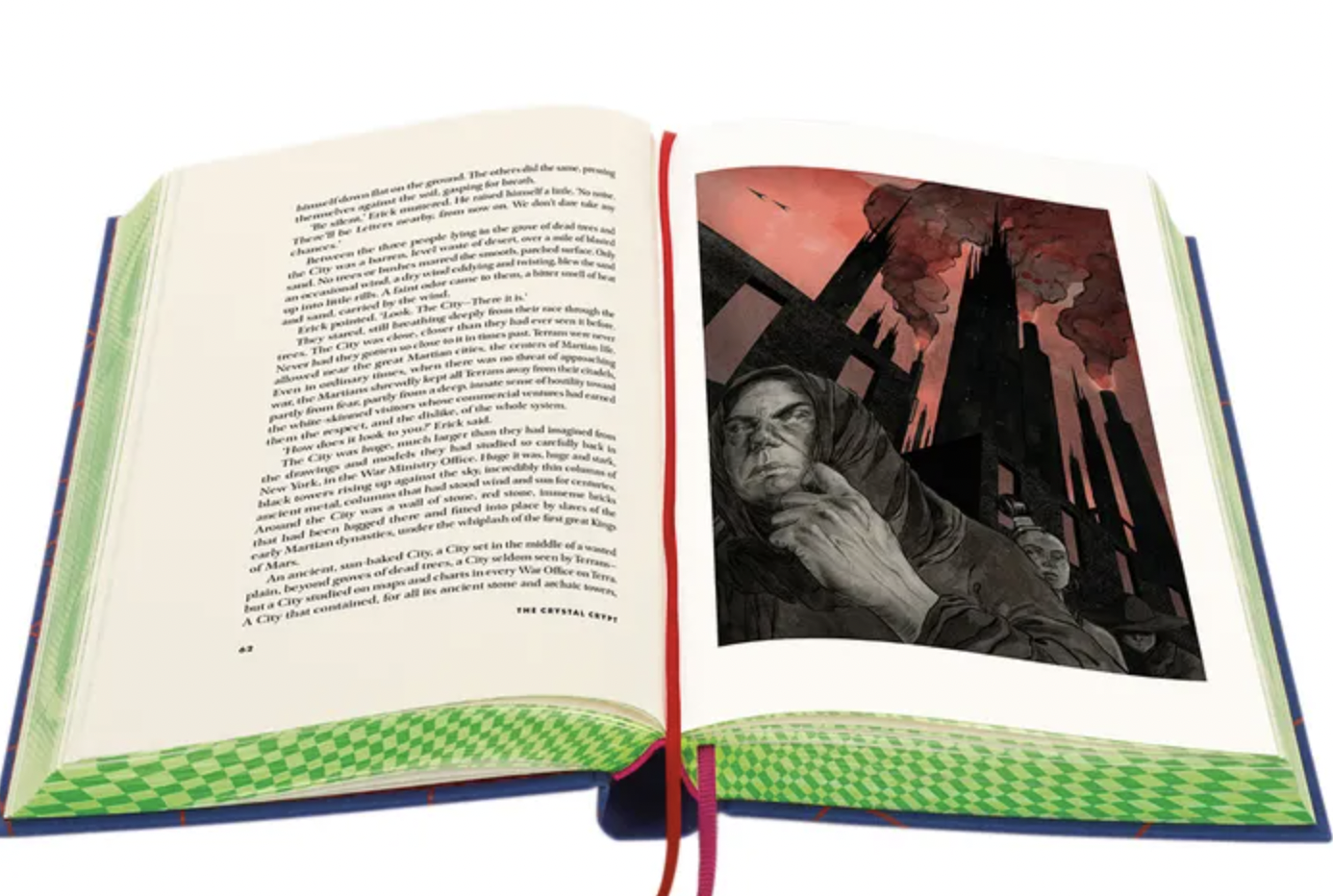

Read More...A Special New, Two-Volume Collection of Philip K. Dick Stories Comes Illustrated by 24 Different Artists

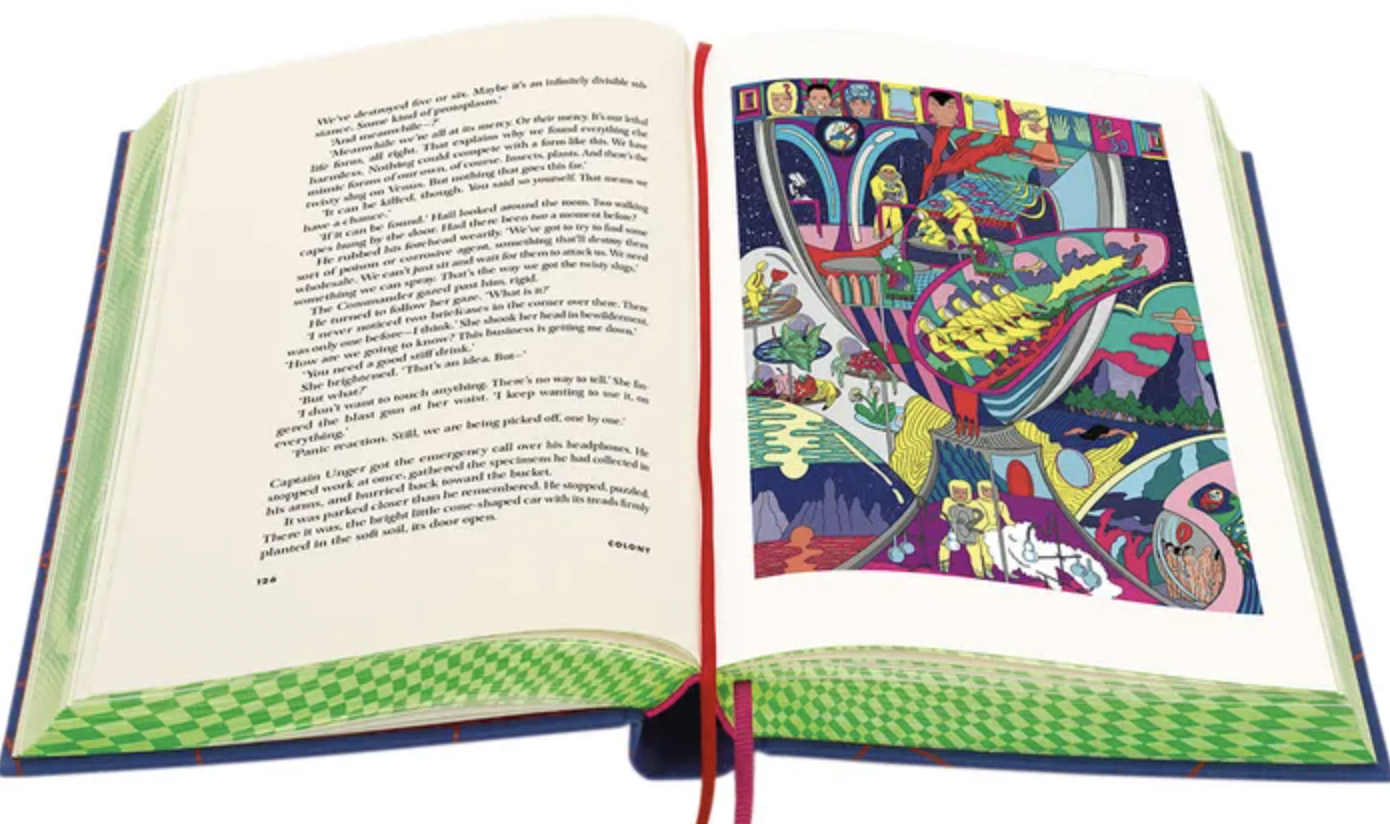

Philip K. Dick’s multiple worlds have appeared in increasingly better editions since the author passed away in 1982. In the 21st century, respectable hardbacks and quality paper have fully replaced yellowed, pulpy pages. Maybe no edition yet is more attractive than the Folio Society of London’s two-volume hardback set of Dick’s selected short stories, illustrated by 24 different artists and including tales that have survived film adaptations, for better and worse, like “Paycheck,” “The Minority Report,” and “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale.” The books will set you back $125, but that’s a small sum compared to the price of an earlier, four-volume Complete Short Stories, published in a limited edition of 750, day-glo, hand-numbered copies. These sold out in less than 48 hours and now go for $2,500 in rare online sales.

In death Dick has achieved what he sought in his writing life: success as literary author. He thought he would eventually publish his realist fiction to earn the reputation, vowing in 1960 that he would “take twenty to thirty years to succeed as a literary writer.” Instead, he’s famous for great fiction that just happens to use the idiom of sci-fi to ask, as he wrote in an undelivered 1978 speech: “What is reality?” and “What constitutes an authentic human being?”

We tend to associate these existential, pre-post-modernist questions with novels and novellas from the 60s and 70s that communicate Dick’s paranoid worldview — works nominated for a Nebula Award, for example, like Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the source for the best of the film adaptations, Blade Runner.

Dick first won fame in 1963 when he was given the Hugo Award for The Man in the High Castle, a book that exceeds the boundaries of genre to become, unmistakably, a PKD original. His earlier stories, on the other hand, written throughout the 1950s when the author was in his twenties, tend to follow the conventions of the hard sci-fi of the time, with the same themes of space travel, robotics, and other futuristic technology that predominate in Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov. Superficially, there might seem little to distinguish Dick’s early stories from other writing of the time published in pulps like Science Fiction Quarterly, Galaxy Science Fiction, and IF.

But the early stories show the unmistakable touch of the later novelist. There are the flashes of humor, absurdity, deep insight into the human psyche, and the warmth and empathy Dick’s narrative voice never lost even in his most bizarre fugues. In his first published story, “Roog,” sold in 1951, Dick imagines a dog who believes the garbage men come to steal the family’s food, leaving only the empty metal storage can behind. “Certainly, I decided,” he writes, “that dog sees the world quite differently than I do, or any humans. And then I began to think, maybe each human being lives in a unique world, a private world, a world different from those inhabited and experienced by all other humans.”

It’s a short leap from these thoughts to the idea that there might be no singular reality at all to fight over. Back then, he says, “I had no idea that such fundamental issues could be pursued in the science fiction field. I began to pursue them unconsciously.” His unconscious led him, in 1954’s “Adjustment Team” — the source of a less-than-great film — to imagine another dog, one who talks and interferes in human affairs (a detail omitted, thankfully, from The Adjustment Bureau). Dick’s early stories often featured comical animals — such as the Okja-like Martian pig in “Beyond Likes the Wub,” a highly-intelligent creature capable of telepathy and deep feeling. While he would turn his attention from animals and aliens to androids, alternate realities, and altered states of consciousness, Dick always had the ability to turn the genre of science fiction into a literary tool for the most daring of philosophical investigations.

Learn more about the two-volume Folio Society Selected Stories of Philip K. Dick here.

Related Content:

33 Sci-Fi Stories by Philip K. Dick as Free Audio Books & Free eBooks

Hear 6 Classic Philip K. Dick Stories Adapted as Vintage Radio Plays

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Remembering Dave Smith (RIP), the Father of MIDI & the Creator of the 80s’ Most Beloved Synthesizer, the Prophet‑5

Some founders rest on their laurels, build industries around themselves like a cocoon, and never escape or outgrow the big achievement that made their name. Some, like Dave Smith — the so-called “father of MIDI,” and one of the most innovative synthesizer pioneers of the last several decades – don’t stop creating for long enough to collect dust. You may never have heard of Smith, but you’ve heard his technology. Before pioneering MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface), the digital standard that allows hundreds of electronic instruments to play nicely with each other across computer and software makers, Smith founded Sequential Circuits and built one of the most revered synthesizers ever made, the Prophet‑5, invented in 1977 and essential to the sound of the 1980s and beyond.

Smith’s keyboards made appearances on stage, video, and albums throughout the decade. Duran Duran’s Nick Rhodes used the Prophet‑5 on the band’s first album and “virtually every record I have made since then,” he said in a statement. “Without Dave’s vision and ingenuity,” Rhodes went on, “the sound of the 1980s would have been very different, he truly changed the sonic soundscape of a generation.”

Sequential synths appeared on albums by bands as disparate as The Cure and Daryl Hall & John Oates, who demonstrate the dream-like, ethereal capabilities of the Prophet‑5 — the first fully programmable polyphonic analog synth — in “I Can’t Go for That (No Can Do).” The Prophet‑5 also drove the sound of Radiohead’s Kid A, and indie dance darlings Hot Chip wrote they would be “nothing without what [Smith] created.” Few vintage synths are as desirable as the Prophet‑5.

The original Prophet is “not immune to the dark side of vintage synths,” writes Vintage Synth Explorer, including problems such as unstable tuning and a lack of MIDI. Smith fixed that issue himself with new iterations of the Prophet and other synths featuring his most famous post-Prophet‑5 technology. “Like so many brilliant and creative people,” the MIDI Association writes, Smith “always focused on the future.” He was “not actually a big fan of being called the ‘Father of MIDI.’ ” Many people contributed to the development of the technology, especially Roland founder Ikutaro Kakehashi, who won a technical Grammy with Smith in 2013 for the protocol that made its debut as a new standard in 1983.

Smith preferred making hardware instruments and “almost begrudgingly accepted interviews about his contributions to MIDI.…. He was also not a big fan of organizations, committees and meetings.” He was a synth lover’s synth maker, a designer and engineer with a “deep understanding of what musicians wanted,” says Rhodes. Collaborations with Yamaha and Korg produced more software innovations in the 90s, but in the 2000s, Smith returned to Sequential Circuits and debuted the Prophet X, Prophet‑6, and OB‑6 with Tom Oberheim. The two designers collaborated in 2021 on the Oberheim OB-X8 and Smith introduced it just weeks before his death.

He had traveled a long way from inventing the Prophet‑5 in 1977 and presenting a paper in 1981 to the Audio Engineering Society on what he then called a Universal Synthesizer Interface. Smith himself never seemed to stop and look back, but lovers of his famous instruments are happy we still can, and that electronic instruments and computers can talk to each other easily thanks to MIDI. Few of those instruments sound as good as the original, however. See a demonstration of the Prophet-5’s range of sounds in the video just above and hear more tracks that show off the synth in the list here.

Related Content:

The Story of the SynthAxe, the Astonishing 1980s Guitar Synthesizer: Only 100 Were Ever Made

Wendy Carlos Demonstrates the Moog Synthesizer on the BBC (1970)

Thomas Dolby Explains How a Synthesizer Works on a Jim Henson Kids Show (1989)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...How Did Cartographers Create World Maps before Airplanes and Satellites? An Introduction

Regular readers of Open Culture know a thing or two about maps if they’ve paid attention to our posts on the history of cartography, the evolution of world maps (and why they are all wrong), and the many digital collections of historical maps from all over the world. What does the seven and a half-minute video above bring to this compendium of online cartographic knowledge? A very quick survey of world map history, for one thing, with stops at many of the major historical intersections from Greek antiquity to the creation of the Catalan Atlas, an astonishing mapmaking achievement from 1375.

The upshot is an answer to the very reasonable question, “how were (sometimes) accurate world maps created before air travel or satellites?” The explanation? A lot of history — meaning, a lot of time. Unlike innovations today, which we expect to solve problems near-immediately, the innovations in mapping technology took many centuries and required the work of thousands of travelers, geographers, cartographers, mathematicians, historians, and other scholars who built upon the work that came before. It started with speculation, myth, and pure fantasy, which is what we find in most geographies of the ancient world.

Then came the Greek Anaximander, “the first person to publish a detailed description of the world.” He knew of three continents, Europe, Asia, and Libya (or North Africa). They fit together in a circular Earth, surrounded by a ring of ocean. “Even this,” says Jeremy Shuback, “was an incredible accomplishment, roughed out by who knows how many explorers.” Sandwiched in-between the continents are some known large bodies of water: the Mediterranean, the Black Sea, the Phasis (modern-day Rioni) and Nile Rivers. Eventually Eratosthenes discovered the Earth was spherical, but maps of a flat Earth persisted. Greek and Roman geographers consistently improved their world maps over succeeding centuries as conquerers expanded the boundaries of their empires.

Some key moments in mapping history involve the 2nd century AD geographer and mathematician Marines of Tyre, who pioneered “equirectangular projection and invented latitude and longitude lines and mathematical geography.” This paved the way for Claudius Ptolemy’s hugely influential Geographia and the Ptolemaic maps that would eventually follow. Later Islamic cartographers “fact checked” Ptolemy, and reversed his preference for orienting North at the top in their own mappa mundi. The video quotes historian of science Sonja Brenthes in noting how Muhammad al-Idrisi’s 1154 map “served as a major tool for Italian, Dutch, and French mapmakers from the sixteenth century to the mid-eighteenth century.”

The invention of the compass was another leap forward in mapping technology, and rendered previous maps obsolete for navigation. Thus cartographers created the portolan, a nautical map mounted horizontally and meant to be viewed from any angle, with wind rose lines extending outward from a center hub. These developments bring us back to the Catalan Atlas, its extraordinary accuracy, for its time, and its extraordinary level of geographical detail: an artifact that has been called “the most complete picture of geographical knowledge as it stood in the later Middle Ages.”

Created for Charles V of France as both a portolan and mappa mundi, its contours and points of reference were not only compiled from centuries of geographic knowledge, but also from knowledge spread around the world from the diasporic Jewish community to which the creators of the Atlas belonged. The map was most likely made by Abraham Cresques and his son Jahuda, members of the highly respected Majorcan Cartographic School, who worked under the patronage of the Portuguese. During this period (before massacres and forced conversions devastated the Jewish community of Majorca in 1391), Jewish doctors, scholars, and scribes bridged the Christian and Islamic worlds and formed networks that disseminated information through both.

In its depiction of North Africa, for example, the Catalan Atlas shows images and descriptions of Malian ruler Mansa Musa, the Berber people, and specific cities and oases rather than the usual dragons and monsters found in other Medieval European maps — despite the cartographers’ use of the works like the Travels of John Mandeville, which contains no shortage of bizarre fiction about the region. While it might seem miraculous that humans could create increasingly accurate views of the Earth from above without flight, they did so over centuries of trial and error (and thousands of lost ships), building on the work of countless others, correcting the mistakes of the past with superior measurements, and crowdsourcing as much knowledge as they could.

To learn more about the fascinating Catalan Atlas, see the Flash Point History video above and the scholarly description found here. Find translations of the map’s legends here at The Cresque Project.

Related Content:

Download 91,000 Historic Maps from the Massive David Rumsey Map Collection

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...