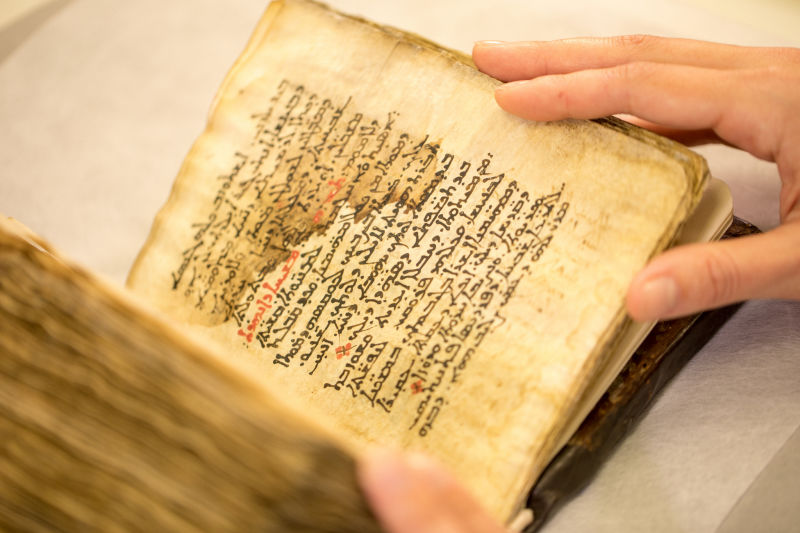

Hidden Ancient Greek Medical Text Read for the First Time in a Thousand Years — with a Particle Accelerator

Image by Farrin Abbott/SLAC, via Flickr Commons

Long before humanity had paper to write on, we had papyrus. Made of the pith of the wetland plant Cyperus papyrus and first used in ancient Egypt, it made for quite a step up in terms of convenience from, say, the stone tablet. And not only could you write on it, you could rewrite on it. In that sense it was less the paper of its day than the first-generation video tape: given the expense of the stuff, it often made sense to erase the content already written on a piece of papyrus in order to record something more timely. But you couldn’t completely obliterate the previous layers of text, a fact that has long held out promise to scholars of ancient history looking to expand their field of primary sources.

The decidedly non-ancient solution: particle accelerators. Researchers at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) recently used one to find the hidden text in what’s now called the Syriac Galen Palimpsest. It contains, somewhere deep in its pages, “On the Mixtures and Powers of Simple Drugs,” an “important pharmaceutical text that would help educate fellow Greek-Roman doctors,” writes Amanda Solliday at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

Originally composed by Galen of Pergamon, “an influential physician and a philosopher of early Western medicine,” the work made its way into the 6th-century Islamic world through a translation into a language between Greek and Arabic called Syriac.

Image by Farrin Abbott/SLAC, via Flickr Commons

Alas, “despite the physician’s fame, the most complete surviving version of the translated manuscript was erased and written over with hymns in the 11th century – a common practice at the time.” Palimpsest, the word coined to describe such texts written, erased, and written over on pre-paper materials like papyrus and parchment, has long since had a place in the lexicon as a metaphor for anything long-historied, multi-layered, and fully understandable only with effort. The Stanford team’s effort involved a technique called X‑ray fluorescence (XRF), whose rays “knock out electrons close to the nuclei of metal atoms, and these holes are filled with outer electrons resulting in characteristic X‑ray fluorescence that can be picked up by a sensitive detector.”

Those rays “penetrate through layers of text and calcium, and the hidden Galen text and the newer religious text fluoresce in slightly different ways because their inks contain different combinations of metals such as iron, zinc, mercury and copper.” Each of the leather-bound book’s 26 pages takes ten hours to scan, and the enormous amounts of new data collected will presumably occupy a variety of experts on the ancient world — on the Greek and Islamic civilizations, on their languages, on their medicine — for much longer thereafter. But you do have to wonder: what kind of unimaginably advanced technology will our descendants a millennium and a half years from now be using to read all of the stuff we thought we’d erased?

Related Content:

The Turin Erotic Papyrus: The Oldest Known Depiction of Human Sexuality (Circa 1150 B.C.E.)

Try the Oldest Known Recipe For Toothpaste: From Ancient Egypt, Circa the 4th Century BC

Learn Ancient Greek in 64 Free Lessons: A Free Course from Brandeis & Harvard

Introduction to Ancient Greek History: A Free Online Course from Yale

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Meet Nadia Boulanger, “The Most Influential Teacher Since Socrates,” Who Mentored Philip Glass, Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, Quincy Jones & Other Legends

We recently featured a video of Brian Eno giving controversial advice to artists: “don’t get a job.” Easier said than done, of course, but he makes a compelling case. Along the way, he says something interesting about the fetish we make of genius—an obsessive focus on lone, and almost always male, artists as self-made, heroic embodiments of greatness. “Although great new ideas are usually articulated by individuals,” he says, “they’re nearly always generated by communities.” (He proposes the neologism “scenius” in place of “genius” to describe “cooperative intelligence.”) Eno would probably agree that great art not only comes out of creative communities of peers, but also from the influence of great teachers.

One such figure, Nadia Boulanger (1887 –1979), has been described as “the most influential teacher since Socrates.” This is hardly hyperbole. As Clemency Burton-Hill notes at the BBC, “her roster of music students reads like the ultimate 20th Century Hall of Fame. Leonard Bernstein. Aaron Copland. Quincy Jones. Astor Piazzolla. Philip Glass,” and so on.

“It is no exaggeration, then, to consider Boulanger the most important musical pedagogue of the modern—or indeed any—era.” She was also a talented composer, a mentor and fierce champion of Igor Stravinsky, and the first woman to conduct major symphonies in Europe and the U.S., such as the New York Philharmonic and the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Boulanger had her own take on genius: “We are as fools to say, ‘he’s a genius,’” she opines in the interview at the top. She also describes her method of weeding out unserious students by asking them, “Can you live without music?” If the answer is yes, she tells them “thank the Lord and goodbye!” Even at an advanced age, her fiercely uncompromising approach is palpable, a quality Philip Glass remembers from his first meeting with her in 1964, when “she was already a relic,” writes Matthew Guerrieri at Red Bull Academy. She identified a bar from one of Glass’s compositions as “written by a real composer,” says Glass. “It was “the first and last time she said anything nice to me for the next two years.”

American composers subjected themselves to Boulanger’s harsh discipline as a “rite of passage,” visiting her in her Paris apartment where she did most of her teaching. She also made her way through “leading conservatoires,” Burton-Hill notes, “including the Juilliard School, the Yehudi Menuhin School, the Royal College of Music and the Royal Academy of Music.” Boulanger’s early life is as fascinating as her teaching career; she was the definition of “a tough, aristocratic Frenchwoman,” as Glass describes her, and grew up surrounded by music. Her father, Ernest, was a composer, conductor, and singing professor. Her younger sister Lili, who died in 1918 at the age of 24, was the more talented composer. (Nadia, writes Burton-Hill, was “riven with envy.”)

A few years after Lili’s tragic death, Nadia abandoned composition to focus primarily on her teaching, mentoring students with tremendous promise and those with less evident gifts alike. “Anyone could be a Boulanger student,” Guerrieri writes (provided they couldn’t live without music): “Those with lesser skills were taken in alongside prodigies and professionals.” She did not discriminate on any basis, though her political attitudes make her a difficult figure for many people to fully embrace. “She espoused nationalism, monarchism and, although her good manners kept it from her often-Jewish students, anti-Semitism.” She held democracy in contempt and did not believe women should vote. And she was especially hard on her female students. (When one woman finally met her approval, Boulanger addressed her as “Monsieur.”)

Boulanger was as traditional in her musical attitudes—spurning Arnold Schoenberg’s innovations, for example—as in her politics. Yet she worked with jazz musicians like Jones and Donald Byrd, and with composers like Joe Raposo, “the musical chameleon behind the songs of Sesame Street and The Electric Company.” She was an encouraging presence in the lives of her students long after they had gone on to success and fame. When Leonard Bernstein sent her the score to West Side Story, she pronounced, “I am enchanted by its dazzling nature” (though she added a critique about its “facility”). Perhaps her most radical student, Philip Glass, has never been accused of musical conservatism. But through his difficult course of study with Boulanger, he says, “I learned to hear.”

“To undergo Boulanger’s rigorous training,” writes Guerrieri, “was to absorb her sense of music history: evolution, not revolution.” Then again, many of history’s revolutionaries have also been some of the keenest students of tradition, usually assisted, guided, and trained by history’s great teachers.

via @dark_shark/Red Bull Academy

Related Content:

A Minimal Glimpse of Philip Glass

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Read More...Brian Eno’s Advice for Those Who Want to Do Their Best Creative Work: Don’t Get a Job

“Once upon a time, artists had jobs,” writes Katy Waldman in a recent New York Times Magazine piece. “Think of T.S. Eliot, conjuring ‘The Waste Land’ (1922) by night and overseeing foreign accounts at Lloyds Bank during the day, or Wallace Stevens, scribbling lines of poetry on his two-mile walk to work, then handing them over to his secretary to transcribe at the insurance agency where he supervised real estate claims.” Or Willem de Kooning painting signs, James Dickey writing slogans for Coca-Cola, William Carlos Williams writing prescriptions, Philip Glass installing dishwashers – the list goes on.

Waldman suggests that we consider day jobs not just bill-paying grinds but delivery systems for “the same replenishing ministries as sleep or a long run: relieving creative angst, restoring the artist to her body and to the texture of immediate experience.” Brian Eno thinks differently. “I often get asked to come and talk at art schools,” he says in the clip above, “and I rarely get asked back, because the first thing I always say is, ‘I’m here to persuade you not to have a job.’ ”

That doesn’t mean, he emphasizes, that you should “try not to do anything. It means try to leave yourself in a position that you do the things you want to do with your time, and where you take maximum advantage of whatever your possibilities are.”

Easier said than done, of course, which is why Eno wants to “work to a future where everybody is in a position to do that,” enacting some form of universal basic income, the general idea of which holds that society will function better if it guarantees all its members a certain standard of living regardless of employment status. But if that standard rises too high, might it run the risk of softening the rigors and loosening the limitations needed to encourage true creativity? Musician Daniel Lanois, who has worked with Eno on the production of several U2 albums as well as ambient music projects, describes learning that lesson from his collaborator in the Louisiana Channel video just above.

“At the peak of my sonic experimentations with Brian Eno, we only ever used four boxes,” says Lanois. “That’s when we started getting these really beautiful textures and human-like sounds from machines. We got to be experts at those few tools.” The limitations under which they worked in the studio may not have followed from any particular philosophy, but the actual experience taught them how a richer artistic result can arise, paradoxically, from more straitened circumstances. Since the beginning of art, its practitioners have always had to find innovative ways around obstacles, whether those obstacles have to do with technology, sides, time, money, or anything else besides. As Lanois reassuringly puts it, “I can imagine that if you have limitation, even financial limitation, that might be okay, man.”

Related Content:

William Faulkner Resigns From His Post Office Job With a Spectacular Letter (1924)

Charles Bukowski Rails Against 9‑to‑5 Jobs in a Brutally Honest Letter (1986)

Brian Eno Explains the Loss of Humanity in Modern Music

The Genius of Brian Eno On Display in 80 Minute Q&A: Talks Art, iPad Apps, ABBA, & MoreBrian Eno on Why Do We Make Art & What’s It Good For?: Download His 2015 John Peel Lecture

The Employment: A Prize-Winning Animation About Why We’re So Disenchanted with Work Today

Hear Alan Watts’s 1960s Prediction That Automation Will Necessitate a Universal Basic Income

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

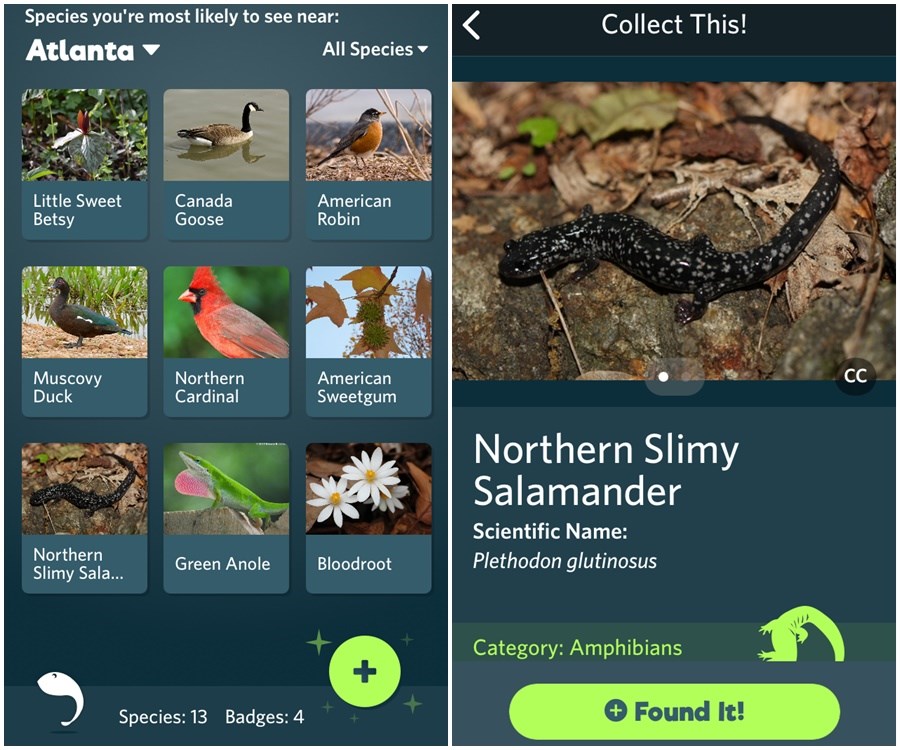

Read More...A Shazam for Nature: A New Free App Helps You Identify Plants, Animals & Other Denizens of the Natural World

Do you ever long for those not-so-long-ago days when you skipped through the world, breathless with the anticipation of catching Pokémon on your phone screen?

If so, you might enjoy bagging some of the Pokeverse’s real world counterparts using Seek, iNaturalist’s new photo-identification app. It does for the natural world what Shazam does for music.

Aim your phone’s camera at a nondescript leaf or the grasshopper-ish-looking creature who’s camped on your porch light. With a bit of luck, Seek will pull up the relevant Wikipedia entry to help the two of you get better acquainted.

Registered users can pin their finds to their personal collections, provided the app’s recognition technology produces a match.

(Several early adopters suggest it’s still a few houseplants shy of true functionality…)

Seek’s protective stance with regard to privacy settings is well suited to junior specimen collectors, as are the virtual badges with which it rewards energetic uploaders.

While it doesn’t hang onto user data, Seek is building a photo library, composed in part of user submissions.

(Your cat is ready for her close up, Mr. DeMille…)

(Ditto your Portobello Mushroom burger…)

Download Seek for free on iTunes or Google Play.

Related Content:

Two Million Wondrous Nature Illustrations Put Online by The Biodiversity Heritage Library

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

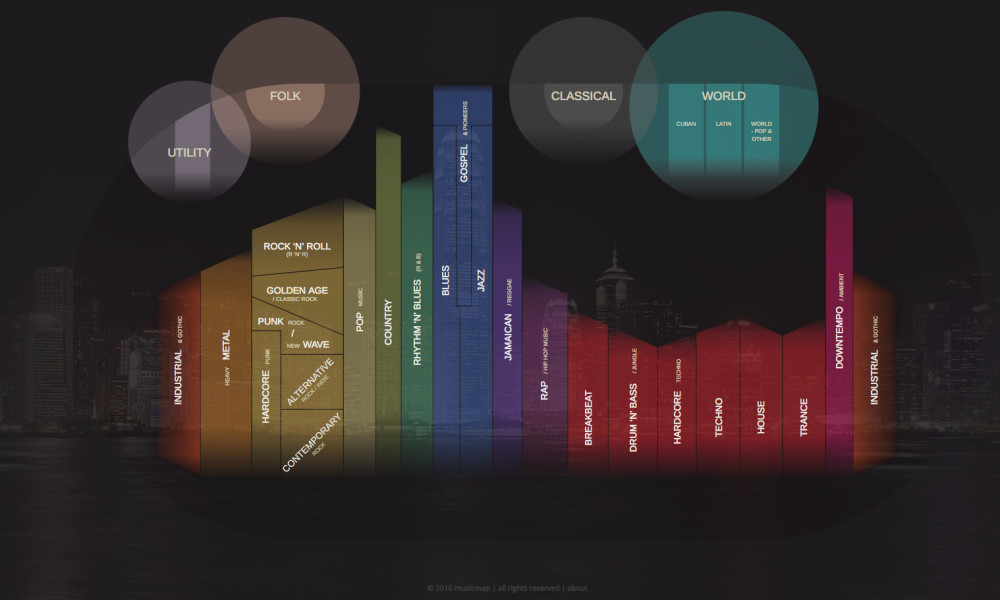

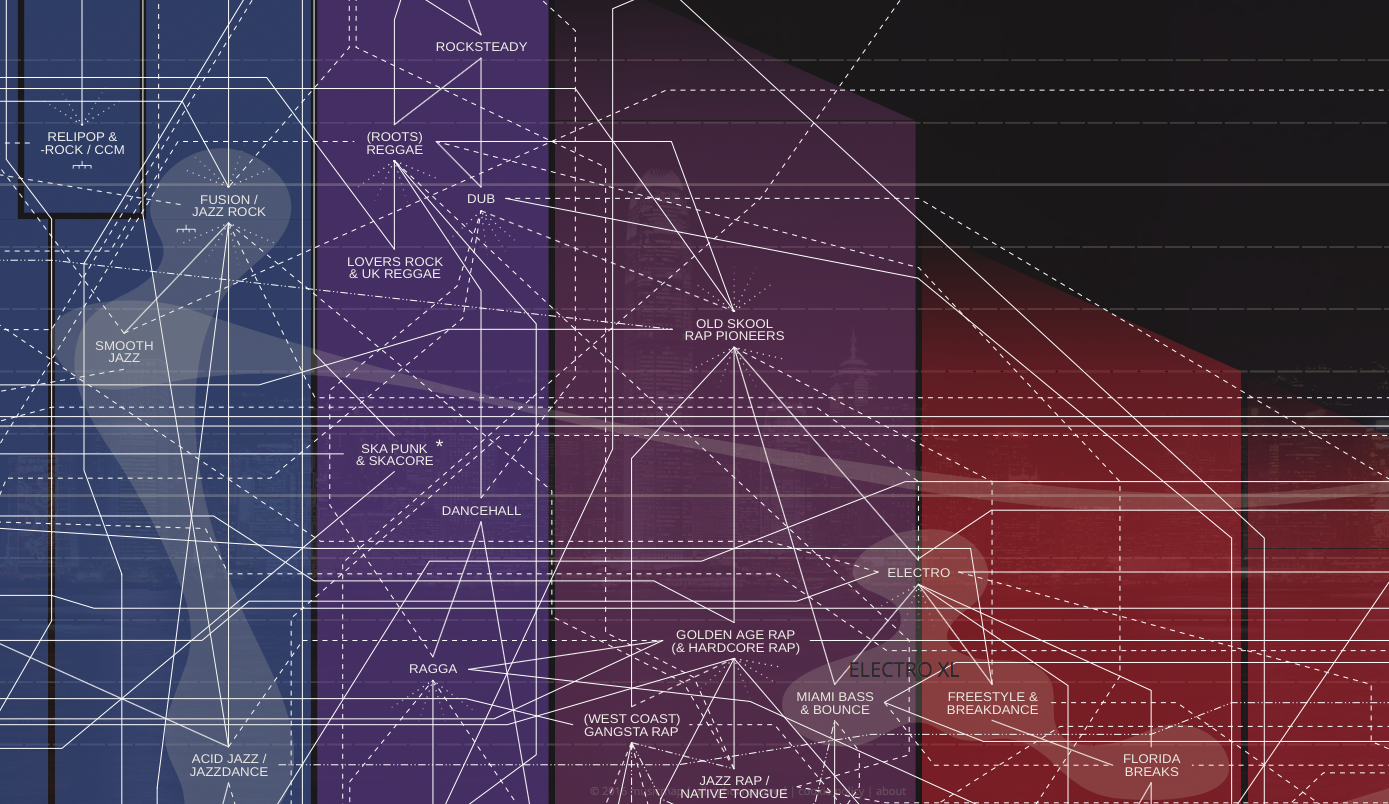

Read More...Behold the MusicMap: The Ultimate Interactive Genealogy of Music Created Between 1870 and 2016

A Pandora for the adventurous antiquarian, the highly underrated site Radiooooo gives users streaming music from all over the world and every decade since 1900. While it offers an aural feast, its limited interface leaves much to be desired from an educational standpoint. On the other end of the audio-visual spectrum, clever diagrams like those we’ve featured here on electronic music, alternative, and hip hop show the detailed connections between all the major acts in these genres, but all they do so in silence.

Now a new interactive infographic built by Belgian architect Kwinten Crauwels brings together an encyclopedic visual reference with an exhaustive musical archive. Though it’s missing some of the features of the resources above, the Musicmap far surpasses anything of its kind online—“both a 23and me-style ancestral tree and a thorough disambiguation of just about every extant genre of music,” writes Fast Company.

Or as Frank Jacobs explains at Big Think, Crauwels’ goal is “to provide the ultimate genealogy of popular music genres, including their relations and history.”

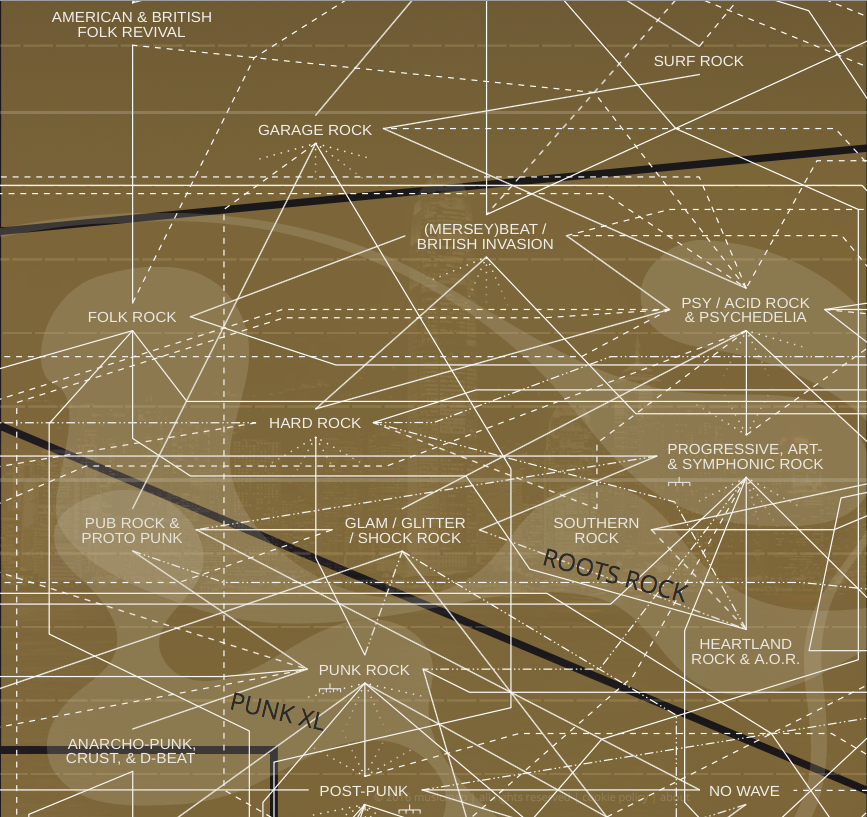

With over 230 genres in all—linked together in intricate webs of influence, mapped in a zoomable visual interface that organizes them all at macro and micro levels of description, and linked to explanatory articles and representative playlists (drawn from YouTube)—the project is almost too comprehensive to believe, and its degree of sophistication almost too complex to summarize concisely (though Jacobs does a good job of it). The Musicmap spans the years 1870–2016 and covers 22 major categories (with Rock further broken into six and “World” into three).

In an oval around the colorful skyscraper-like “super-genres” are decades, moving from past to present from top to bottom. Zoom into the “super-genres” and find “a spider’s web of links within and between the different houses” of subgenres. “Those links can indicate parentage or influence, but also a backlash (i.e. as ‘anti-links’).” Clicking on the name of each subgenre reveals “a short synopsis and a playlist of representative songs.” These two functions, in turn, link to each other, allowing users to click through in a more Wikipedia-like way once they’ve entered the minutiae of the Musicmap’s contents.

The map not only draws connections between subgenres but also between their relatives in other “super-genres” (learn about the relationship, for example, between folk rock and classic metal). On the left side of the screen is a series of buttons that reveal an introduction, methodology, abstract, several navigational functions, a glossary of musical terms, and a bibliography (called “Acknowledgments”). Aside from visually reducing all the way down to the level of individual bands within each subgenre, which could become a little dizzying, it’s hard to think of anything seriously lacking here.

Anything we might find fault with might be changed in the near future. Although Crauwels spent almost ten years on research and development, first conceiving of the project in 2008, the current site “is still version 1.0 of Music map. In later versions, the playlists will be expanded, perhaps even community-generated.” Crauwels also wants to sync up with Spotify. Although not a musician himself, he is as passionate about music as he is about design and education, making him very likely the perfect person to take on this task, which he admits can never be completed.

Crauwels does not currently seem to have plans to monetize his map. His stated motives are altruistic, in the same public service spirit as Radiooooo. “Musicmap,” he says, “believes that knowledge about music genres is a universal right and should be part of basic education.” At the moment, the education here only applies to popular music, although enough of it to acquire a graduate-level historical knowledge base.

The four categories at the top of the map—the strangely named “Utility” (which includes hymns, military marches, musicals, and soundtracks), Folk, Classical, and World—are zoomable but do not have clickable links or playlists. Given Crauwels’ completist instincts, this may well change in future updates. In the TED talk above, see him tell the story of how he created Musicmap, a DIY effort that came out of his frustration that nothing like it existed, so he had to create it himself.

Enter the Musicmap here and try not to get lost for several hours.

via Big Think

Related Content:

Radio Garden Lets You Instantly Tune into Radio Stations Across the Entire Globe

A Massive 800-Track Playlist of 90s Indie & Alternative Music, in Chronological Order

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Hear 48 Hours of Lectures by Joseph Campbell on Comparative Mythology and the Hero’s Journey

What does it mean to “grow up”? Every culture has its way of defining adulthood, whether it’s surviving an initiation ritual or filing your first tax return. I’m only being a little facetious—people in the U.S. have long felt dissatisfaction with the ways we are ushered into adulthood, from learning how to fill out IRS forms to learning how to fill out student loan and credit card applications, our culture wants us to understand our place in the great machine. All other pressing life concerns are secondary.

It’s little wonder, then, that gurus and cultural father figures of all types have found ready audiences among America’s youth. Such figures have left lasting legacies for decades, and not all of them positive. But one public intellectual from the recent past is still seen as a wise old master whose far-reaching influence remains with us and will for the foreseeable future. Joseph Campbell’s obsessive, erudite books and lectures on world mythologies and traditions have made certain that ancient adulthood rituals have entered our narrative DNA.

When Campbell was awarded the National Arts Club Gold Medal in Literature in 1985, psychologist James Hillman stated that “no one in our century—not Freud, not Thomas Mann, not Levi-Strauss—has so brought the mythical sense of the world and its eternal figures back into our everyday consciousness.” Whatever examples Hillman may have had in mind, we might rest our case on the fact that without Campbell there would likely be no Star Wars. For all its success as a megamarketing phenomenon, the sci-fi franchise has also produced enduringly relatable role models, examples of achieving independence and standing up to imperialists, even if they be your own family members in masks.

In the video interviews above from 1987, Campbell professes himself no more than an “underliner” who learned everything he knows from books. Like the contemporary comparative mythologist Mircea Eliade, Campbell did not conduct his own anthropological research—he acquired a vast amount of knowledge by studying the sacred texts, artifacts, and rituals of world cultures. This study gave him insight into stories and images that continue to shape our world and feature centrally in huge pop cultural productions like The Last Jedi and Black Panther.

Campbell describes ritual entries into adulthood that viewers of these films will instantly recognize: Defeating idols in masks and taking on their power; burial enactments that kill the “infantile ego” (academics, he says with a straight face, sometimes never leave this stage). These kinds of edge experiences are at the very heart of the classic hero’s journey, an archetype Campbell wrote about in his bestselling The Hero with a Thousand Faces and popularized on PBS in The Power of Myth, a series of conversations with Bill Moyers.

In the many lectures just above—48 hours of audio in which Campbell expounds his theories of the mythological—the engaging, accessible writer and teacher lays out the patterns and symbols of mythologies worldwide, with special focus on the hero’s journey, as important to his project as dying and rising god myths to James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, the inspiration for so many modernist writers. Campbell himself is more apt to reference James Joyce, Carl Jung, Pablo Picasso, or Richard Wagner than science fiction, fantasy, or comic books (though he did break down Star Wars in his Moyers interviews). Nonetheless, we have him to thank for inspiring the likes of George Lucas and becoming a “patron saint of superheroes” and space operas.

We will find some of Campbell’s methods flawed and terminology outdated (no one uses “Orient” and “Occident” anymore)—and modern heroes can just as well be women as men, passing through the same kinds of symbolic trials in their origin stories. But Campbell’s ideas are as resonant as ever, offering to the wider culture a coherent means of understanding the archetypal stages of coming of age. As Hollywood executive Christopher Vogler said in 1985, after recommending The Hero with a Thousand Faces as a guide for screenwriters, Campbell’s work “can be used to tell the simplest comic story or the most sophisticated drama”—a sweeping vision of human cultural history and its meaning for our individual journeys.

You can access the 48 hours of Joseph Campbell lectures above, or directly on Spotify.

Related Content:

Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers Break Down Star Wars as an Epic, Universal Myth

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...What Happened When Stephen Hawking Threw a Cocktail Party for Time Travelers (2009)

Who among us has never fantasized about traveling through time? But then, who among us hasn’t traveled through time? Every single one of us is a time traveler, technically speaking, moving as we do through one second per second, one hour per hour, one day per day. Though I never personally heard the late Stephen Hawking point out that fact, I feel almost certain that he did, especially in light of one particular piece of scientific performance art he pulled off in 2009: throwing a cocktail party for time travelers — the proper kind, who come from the future.

“Hawking’s party was actually an experiment on the possibility of time travel,” writes Atlas Obscura’s Anne Ewbank. “Along with many physicists, Hawking had mused about whether going forward and back in time was possible. And what time traveler could resist sipping champagne with Stephen Hawking himself?” ”

By publishing the party invitation in his mini-series Into the Universe With Stephen Hawking, Hawking hoped to lure futuristic time travelers. You are cordially invited to a reception for Time Travellers, the invitation read, along with the the date, time, and coordinates for the event. The theory, Hawking explained, was that only someone from the future would be able to attend.”

Alas, no time travelers turned up. Since someone possessed of that technology at any point in the future would theoretically be able to attend, does Hawking’s lonely party, which you can see in the clip above, prove that time travel will never become possible? Maybe — or maybe the potential time-travelers of the future know something about the space-time-continuum-threatening risks of the practice that we don’t. As for Dr. Hawking, I have to imagine that he came away satisfied from the shindig, even though his hoped-for Ms. Universe from the future never walked through the door. “I like simple experiments… and champagne,” he said, and this champagne-laden simple experiment will continue to remind the rest of us to enjoy our time on Earth, wherever in that time we may find ourselves.

Related Content:

The Lighter Side of Stephen Hawking: The Physicist Cracks Jokes and a Smile with John Oliver

Professor Ronald Mallett Wants to Build a Time Machine in this Century … and He’s Not Kidding

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

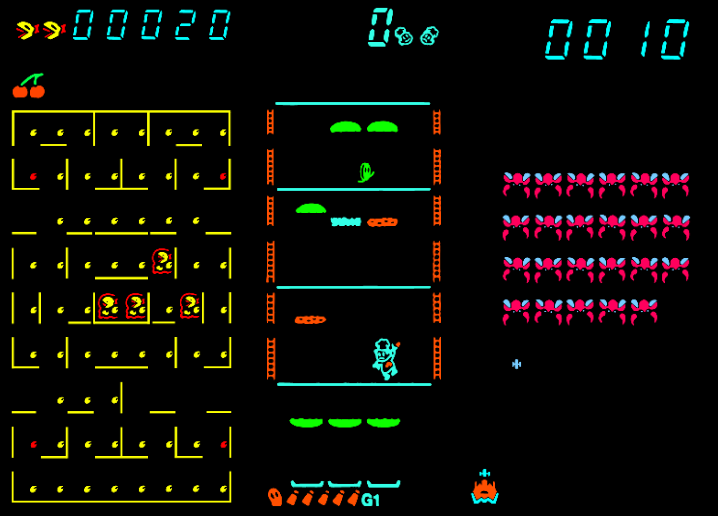

Read More...Play a Collection of Classic Handheld Video Games at the Internet Archive: Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, Tron and MC Hammer

Equipped with smartphones that grow more powerful by the year, gamers on the go now have a seemingly unlimited variety of playing options. A decade ago they relied on handheld game consoles with their thousands of available game cartridges and later discs, whose reign began with Nintendo’s introduction of the original Game Boy (a device whose unwrapping on Christmas 1990 remains one of my most vivid childhood memories). But even before the Game Boy and its successors, there were standalone handheld proto-video-games, “LCD, VFD and LED-based machines that sold, often cheaply, at toy stores and booths over the decades.”

Those words come from Jason Scott at the Internet Archive, where you can now play a range of those handheld games again, emulated right here in your browser. “They range from notably simplistic efforts to truly complicated, many-buttoned affairs that are truly difficult to learn, much less master,” Scott writes.

“They are, of course, entertaining in themselves – these are attempts to put together inexpensive versions of video games of the time, or bringing new properties wholecloth into existence.” They also “represent the difficulty ahead for many aspects of digital entertainment, and as such are worth experiencing and understanding for that reason alone.”

What kind of games came in this form? The Internet Archive’s current offerings include vague approximations of 70s and 80s arcade hits like Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, and Q*Bert; even vaguer approximations of such major motion pictures of the day as Tron, Robocop 2 (as well as Robocop 3), and Apollo 13; and sports titles like World Championship Baseball, NFL Football, and Blades of Steel. You’ll even find popular oddities like Bandai’s Tamagotchi, the original virtual pet, along with less popular oddities like MC Hammer, a dual-directional-padded simulation of a dance battle with the auteur of “U Can’t Touch This.”

So as you play, spare a thought for the developers of these handheld games, not just because of the dire intellectual property they often had to work with, but the severe technological restrictions they invariably had to work under. “This sort of Herculean effort to squeeze a major arcade machine into a handful of circuits and a beeping, booping shell of what it once was is an ongoing situation,” writes Scott. “Where once it was trying to make arcade machines work both on home consoles like the 2600 and Colecovision, so it was also the case of these plastic toy games. Work of this sort continues, as mobile games take charge and developers often work to bring huge immersive experiences to where a phone hits all the same notes.” And the day will certainly come when even the most impressive games we play now, handheld or otherwise, will seem just as hilariously simplistic.

Enter the handheld video collection here. And find more classic video games in the Relateds below.

Related Content:

Play “Space War!,” One of the Earliest Video Games, on Your Computer (1962)

Pong, 1969: A Milestone in Video Game History

The Internet Arcade Lets You Play 900 Vintage Video Games in Your Web Browser (Free)

Free: Play 2,400 Vintage Computer Games in Your Web Browser

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Download 10,000 of the First Recordings of Music Ever Made, Thanks to the UCSB Cylinder Audio Archive

Three minutes with the minstrels / Arthur Collins, S. H. Dudley & Ancient City. Edison Record. 1899.

Long before vinyl records, cassette tapes, CDs and MP3s came along, people first experienced audio recordings through another medium — through cylinders made of tin foil, wax and plastic. In recent years, we’ve featured cylinder recordings from the 19th century that allow you to hear the voices of Leo Tolstoy, Tchaikovsky, Otto von Bismarck and other towering figures. Those recordings were originally recorded and played on a cylinder phonograph invented by Thomas Edison in 1877. But those were obviously just a handful of the cylinder recordings produced at the beginning of the recorded sound era.

Thanks to the University of California-Santa Barbara Cylinder Audio Archive, you can now download or stream a digital collection of more than 10,000 cylinder recordings. “This searchable database,” says UCSB, “features all types of recordings made from the late 1800s to early 1900s, including popular songs, vaudeville acts, classical and operatic music, comedic monologues, ethnic and foreign recordings, speeches and readings.” You can also find in the archive a number of “personal recordings,” or “home wax recordings,” made by everyday people at home (as opposed to by record companies).

If you go to this page, the recordings are neatly categorized by genre, instrument, subject/theme and ethnicity/nation of origin. You can listen, for example, to recordings of Jazz, Ragtime, Operas, and Vaudeville acts. Or hear recordings featuring the Mandolin, Guitar, Dulcimer and Banjo, among other instruments. Plus there are thematically-arranged playlists here.

Hosted by UCSB (UC Santa Barbara), the archive is supported by funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the Grammy Foundation, and other donors.

Above, hear a recording called “Three minutes with the minstrels,” by Arthur Collins, released in 1899. Below that is “Alexander’s ragtime band medley,” featuring the banjo playing of Fred Van Eps, released in 1913.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in November, 2015.

Related Content:

A Beer Bottle Gets Turned Into a 19th Century Edison Cylinder and Plays Fine Music

Voices from the 19th Century: Tennyson, Gladstone, Whitman & Tchaikovsky

Thomas Edison’s Recordings of Leo Tolstoy: Hear the Voice of Russia’s Greatest Novelist

Tchaikovsky’s Voice Captured on an Edison Cylinder (1890)

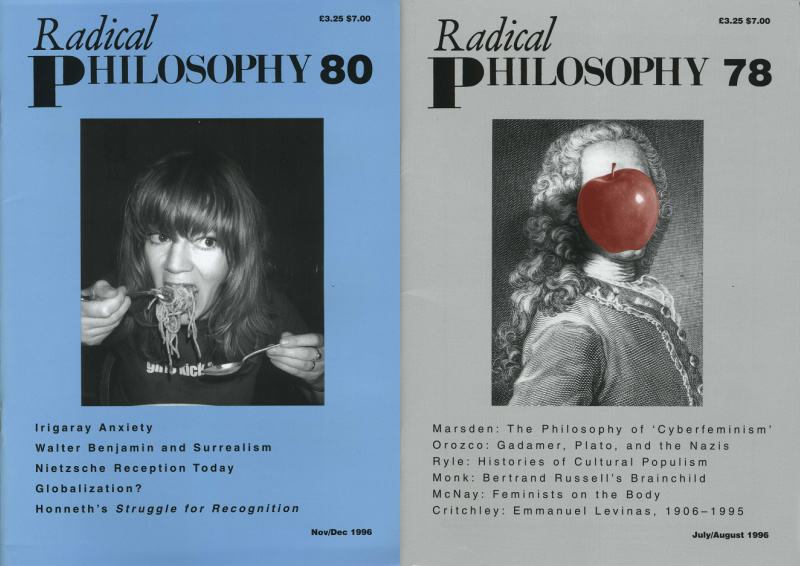

Read More...The Entire Archives of Radical Philosophy Go Online: Read Essays by Michel Foucault, Alain Badiou, Judith Butler & More (1972–2018)

On a seemingly daily basis, we see attacks against the intellectual culture of the academic humanities, which, since the 1960s, have opened up spaces for leftists to develop critical theories of all kinds. Attacks from supposedly liberal professors and centrist op-ed columnists, from well-funded conservative think tanks and white supremacists on college campus tours. All rail against the evils of feminism, post-modernism, and something called “neo-Marxism” with outsized agitation.

For students and professors, the onslaughts are exhausting, and not only because they have very real, often dangerous, consequences, but because they all attack the same straw men (or “straw people”) and refuse to engage with academic thought on its own terms. Rarely, in the exasperating proliferation of cranky, cherry-picked anti-academia op-eds do we encounter people actually reading and grappling with the ideas of their supposed ideological nemeses.

Were non-academic critics to take academic work seriously, they might notice that debates over “political correctness,” “thought policing,” “identity politics,” etc. have been going on for thirty years now, and among left intellectuals themselves. Contrary to what many seem to think, criticism of liberal ideology has not been banned in the academy. It is absolutely the case that the humanities have become increasingly hostile to irresponsible opinions that dehumanize people, like emergency room doctors become hostile to drunk driving. But it does not follow therefore that one cannot disagree with the establishment, as though the University system were still beholden to the Vatican.

Understanding this requires work many people are unwilling to do, either because they’re busy and distracted or, perhaps more often, because they have other, bad faith agendas. Should one decide to survey the philosophical debates on the left, however, an excellent place to start would be Radical Philosophy, which describes itself as a “UK-based journal of socialist and feminist philosophy.” Founded in 1972, in response to “the widely-felt discontent with the sterility of academic philosophy at the time,” the journal was itself an act of protest against the culture of academia.

Radical Philosophy has published essays and interviews with nearly all of the big names in academic philosophy on the left—from Marxists, to post-structuralists, to post-colonialists, to phenomenologists, to critical theorists, to Lacanians, to queer theorists, to radical theologians, to the pragmatist Richard Rorty, who made arguments for national pride and made several critiques of critical theory as an illiberal enterprise. The full range of radical critical theory over the past 45 years appears here, as well as contrarian responses from philosophers on the left.

Rorty was hardly the only one in the journal’s pages to critique certain prominent trends. Sociologists Pierre Bourdieu and Loic Wacquant launched a 2001 protest against what they called “a strange Newspeak,” or “NewLiberalSpeak” that included words like “globalization,” “governance,” “employability,” “underclass,” “communitarianism,” “multiculturalism” and “their so-called postmodern cousins.” Bourdieu and Wacquant argued that this discourse obscures “the terms ‘capitalism,’ ‘class,’ ‘exploitation,’ ‘domination,’ and ‘inequality,’” as part of a “neoliberal revolution,” that intends to “remake the world by sweeping away the social and economic conquests of a century of social struggles.”

One can also find in the pages of Radical Philosophy philosopher Alain Badiou’s 2005 critique of “democratic materialism,” which he identifies as a “postmodernism” that “recognizes the objective existence of bodies alone. Who would ever speak today, other than to conform to a certain rhetoric? Of the separability of our immortal soul?” Badiou identifies the ideal of maximum tolerance as one that also, paradoxically, “guides us, irresistibly” to war. But he refuses to counter democratic materialism’s maxim that “there are only bodies and languages” with what he calls “its formal opposite… ‘aristocratic idealism.’” Instead, he adds the supplementary phrase, “except that there are truths.”

Badiou’s polemic includes an oblique swipe at Stalinism, a critique Michel Foucault makes in more depth in a 1975 interview, in which he approvingly cites phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty’s “argument against the Communism of the time… that it has destroyed the dialectic of individual and history—and hence the possibility of a humanistic society and individual freedom.” Foucault made a case for this “dialectical relationship” as that “in which the free and open human project consists.” In an interview two years later, he talks of prisons as institutions “no less perfect than school or barracks or hospital” for repressing and transforming individuals.

Foucault’s political philosophy inspired feminist and queer theorist Judith Butler, whose arguments inspired many of today’s gender theorists, and who is deeply concerned with questions of ethics, morality, and social responsibility. Her Adorno Prize Lecture, published in a 2012 issue, took up Theodor Adorno’s challenge of how it is possible to live a good life in bad circumstances (under fascism, for example)—a classical political question that she engages through the work of Orlando Patterson, Hannah Arendt, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Hegel. Her lecture ends with a discussion of the ethical duty to actively resist and protest an intolerable status quo.

You can now read for free all of these essays and hundreds more at the Radical Philosophy archive, either on the site itself or in downloadable PDFs. The journal, run by an ‘Editorial Collective,” still appears three times a year. The most recent issue features an essay by Lars T. Lih on the Russian Revolution through the lens of Thomas Hobbes, a detailed historical account by Nathan Brown of the term “postmodern,” and its inapplicability to the present moment, and an essay by Jamila M.H. Mascat on the problem of Hegelian abstraction.

If nothing else, these essays and many others should upend facile notions of leftist academic philosophy as dominated by “postmodern” denials of truth, morality, freedom, and Enlightenment thought, as doctrinaire Stalinism, or little more than thought policing through dogmatic political correctness. For every argument in the pages of Radical Philosophy that might confirm certain readers’ biases, there are dozens more that will challenge their assumptions, bearing out Foucault’s observation that “philosophy cannot be an endless scrutiny of its own propositions.”

Enter the Radical Philosophy archive here.

Related Content:

Introducing Ergo, the New Open Philosophy Journal

History of Modern Philosophy: A Free Online Course

On the Power of Teaching Philosophy in Prisons

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...