The Archive of Healing Is Now Online: UCLA’s Digital Database Provides Access to Thousands of Traditional & Alternative Healing Methods

Photo by Katherine Hanlon on Unsplash

Folk medicine is, or should be, antithetical to capitalism, meaning it should not be possible to trademark, copyright, or otherwise own and sell plants and natural remedies to which everyone has access. The entire reason such practices developed over the course of millennia was to help communities of close affiliation survive and thrive, not to foster market competition between companies and individuals. The impulse to profit from suffering has distorted what we think of as healing, such that a strictly allopathic, or “Western,” approach to medicine relies on ethics of exclusion, exploitation, and outright harm.

What we tend to think of as modern medicine, the Archive of Healing writes, “is object-oriented (pharmaceuticals, technologically driven) and structured by historical injustice against women and people of color.” The Archive, a new digital project from the University of California, Los Angeles, offers “one of the most comprehensive databases of medicinal folklore in the world,” Valentina Di Liscia writes at Hyperallergic. “The interactive, searchable website boasts hundreds of thousands of entries describing cures, rituals, and healing methods spanning more than 200 years and seven continents.”

In countries like the United States, where healthcare is treated as a scarce commodity millions of people cannot afford, access to knowledge about effective, age-old natural wisdom has become critical. There may be no treatments for COVID-19 in the database, but there are likely traditional remedies, rituals, practices, treatments, ointments, etc. for just about every other illness one might encounter. The archive was curated over a period of more than thirty years by “a team of researchers at UCLA, working under the direction of Dr. Wayland Hand and then Dr. Michael Owen Jones,” the site notes in its brief history.

The material from the collection, which was originally called the “archive of traditional medicine,” came from “data on healing from over 3,200 publications, six university archives, as well as first-hand and second-hand information from anthropological and folkloric fieldnotes.” In 2016, when Dr. Delgado Shorter took over as director of the program, he “reorganized it with an eye to social sharing and allowing for users to submit new data and comment on existing data,” notes UCLA’s School of the Arts and Architecture in an interview with Shorter, who describes the project’s aims thus:

The whole goal here is to democratize what we think of as healing and knowledge about healing and take it across cultures in a way that’s respectful and gives attention to intellectual property rights.

This may seem like a delicate balancing act, between the scholarly, the folkloric, and the realms of rights, remuneration, and social power. The Archive strikes it with an ambitious set of tenets you can read here, including an emphasis on offering traditional and Indigenous healing practices “outside of often expensive allopathic and pharmaceutical approaches, and not as alternatives but as complementary modalities.”

The archive states as one of its theoretical bases that health should be treated “as a social goal with social methods that affirm relationality and kinship.” Those wishing to get involved with the Archive as partners or advisory board members can learn how at their About page, which also features the following disclaimer: “Statements made on this website have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. The information contained herein is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.” Use the information wisely, at your own risk, in other words.

To use the Archive of Healing, you will need to register with the site first.

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

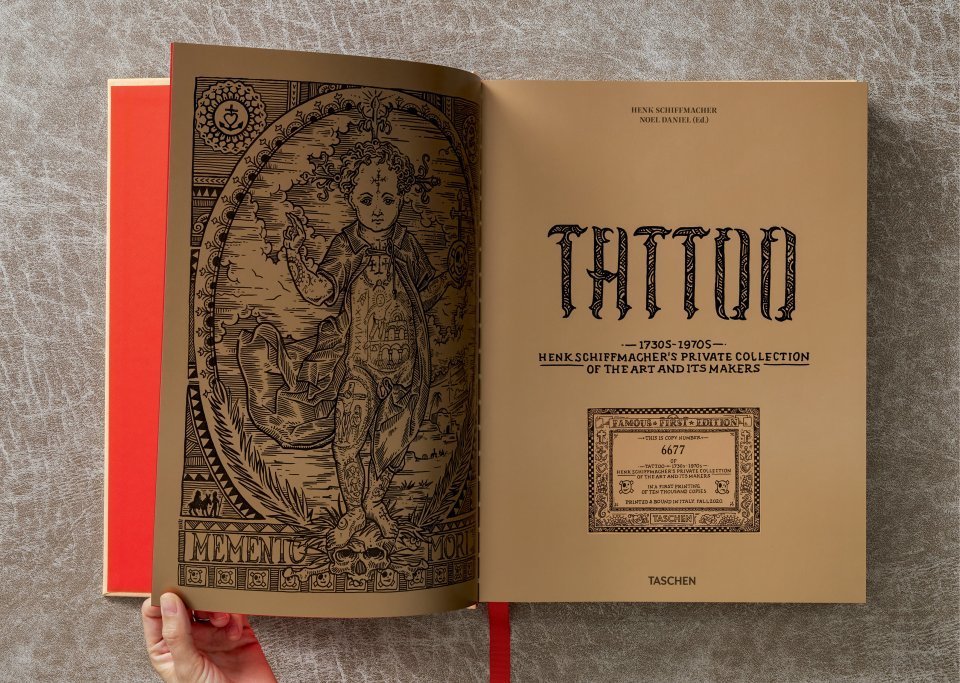

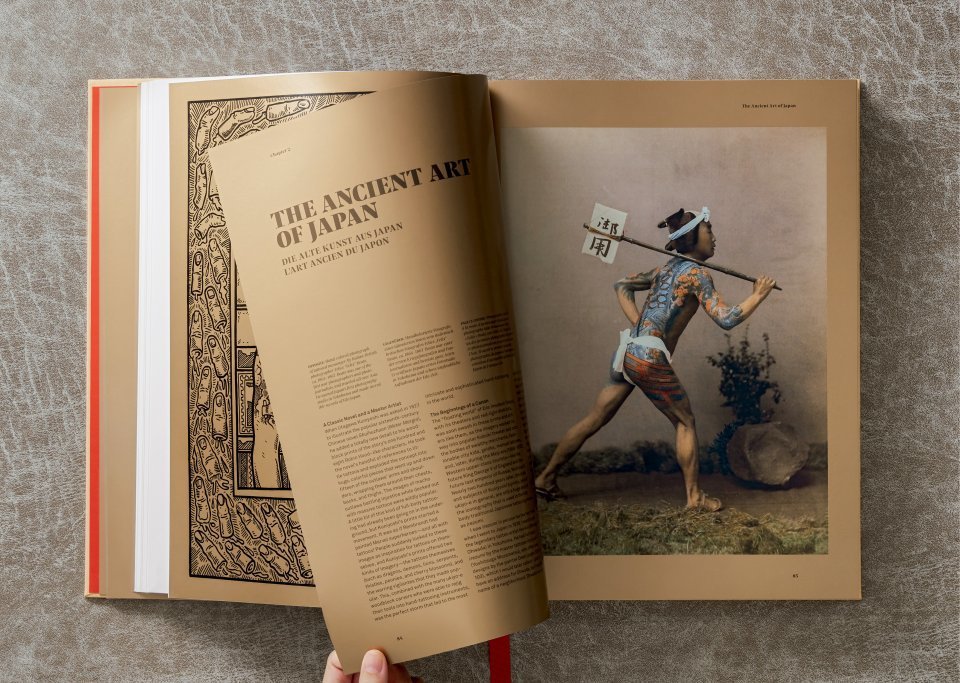

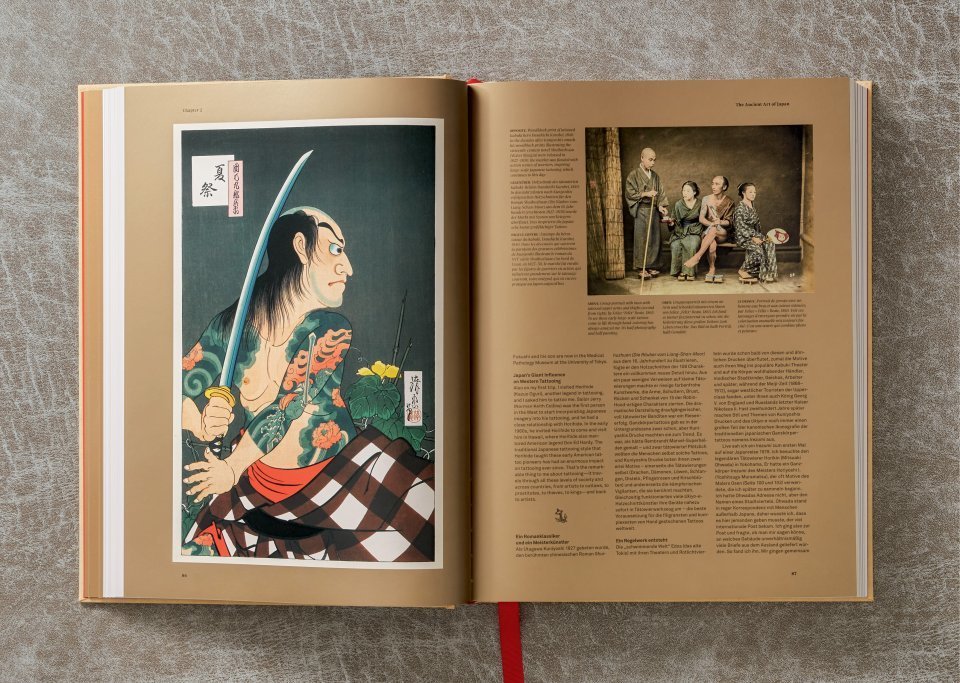

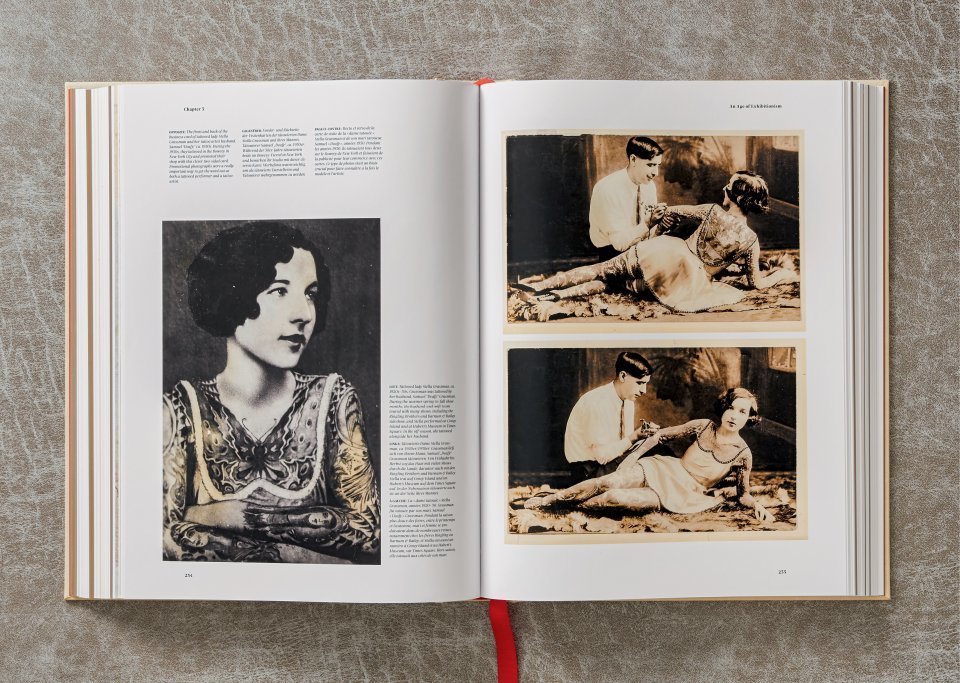

Read More...The History of Tattoos Gets Beautifully Documented in a New Book by Legendary Tattoo Artist Henk Schiffmacher (1730–1970)

I always think tattoos should communicate. If you see tattoos that don’t communicate, they’re worthless. —Henk Schiffmacher, tattoo artist

Tattooing is an ancient art whose grip on the American mainstream, and that of other Western cultures, is a comparatively recent development.

Long before he took up—or went under—a tattoo needle, legendary tattoo artist and self-described “very odd duck type of guy,” Henk Schiffmacher was a fledgling photographer and accidental collector of tattoo lore.

Inspired by the immersive approaches of Diane Arbus and journalist Hunter S. Thompson, Schiffmacher, aka Hanky Panky, attended tattoo conventions, seeking out any subculture where inked skin might reveal itself in the early 70s.

As he shared with fellow tattooer Eric Perfect in a characteristically rollicking, profane interview, his instincts became honed to the point where he “could smell” a tattoo concealed beneath clothing:

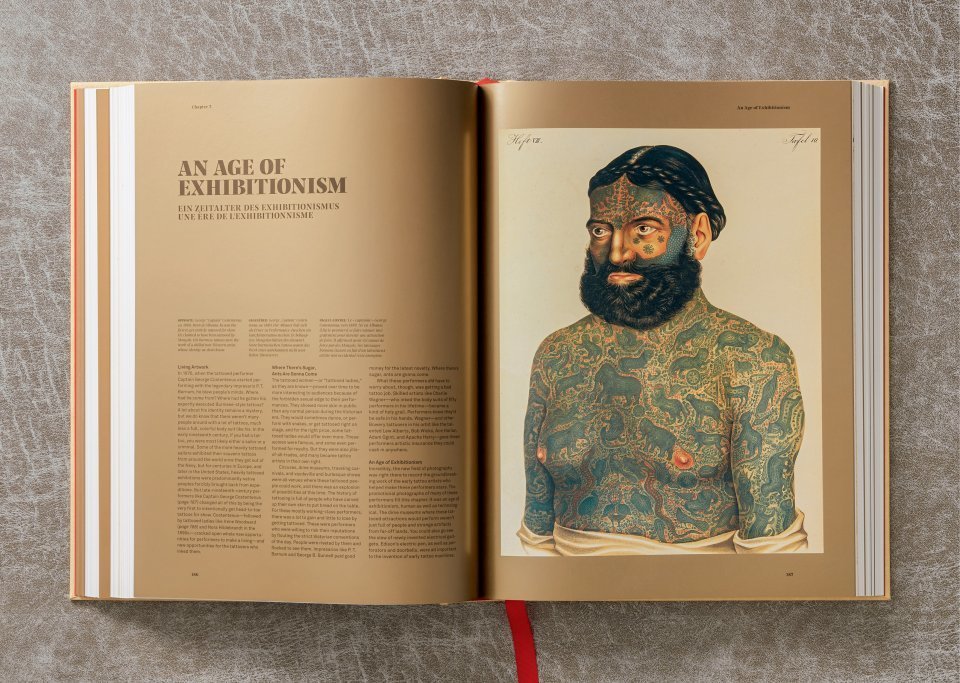

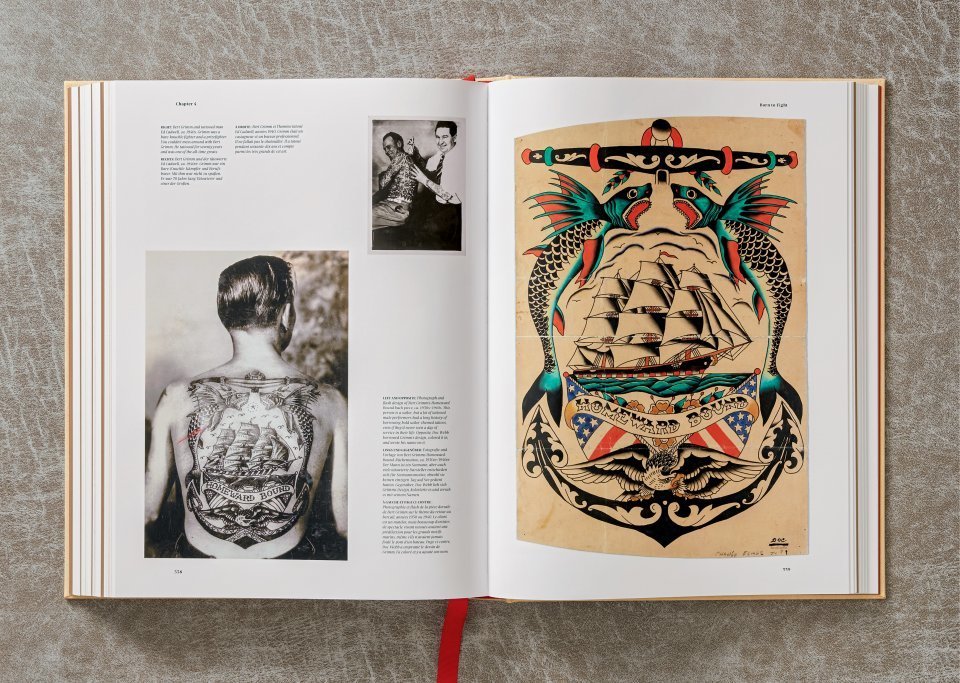

The kind of tattoos you used to see in those days, you do not see anymore, that stuff made in jail, in the German jails, like, you’d like see a guy who’d tattooed himself as far as his right hand could reach and the whole right (side) would be empty…I always loved that stuff which was never meant to be art which is straight from the heart.

When tattoo artists would write to him, requesting prints of his photos, he would save the letters, telling Hero’s Eric Goodfellow:

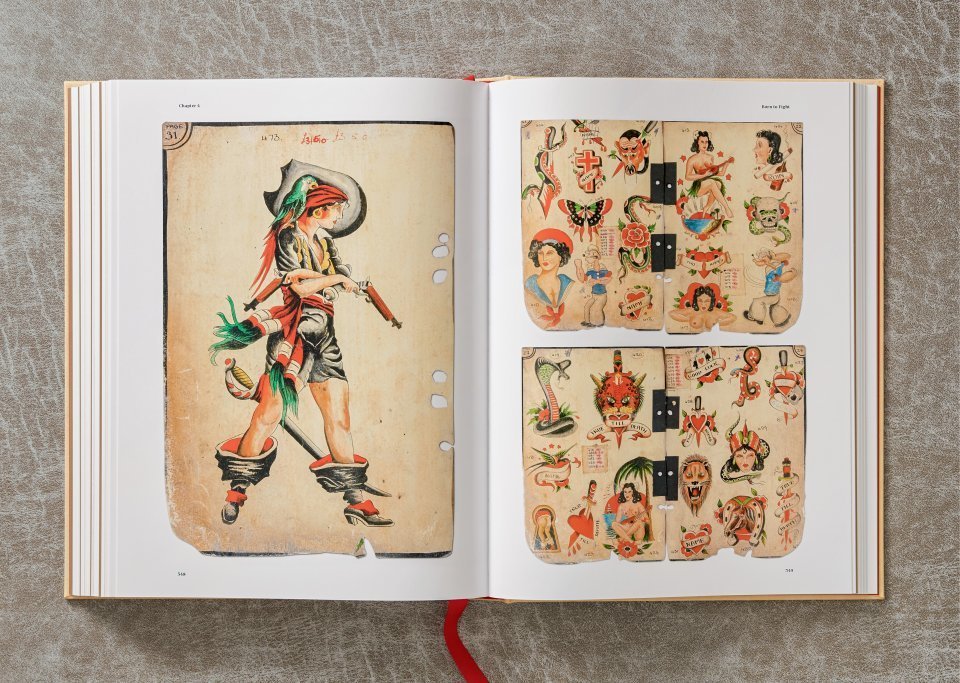

I would get stuff from all over the world. The whole envelope would be decorated, and the letter as well. I have letters from the Leu Family and they’re complete pieces of art, they’re hand painted with all kinds of illustrations. Also people from jail would write letters, and they would take time to write in between the lines in a different colour. So very, very unique letters.

Such correspondence formed the earliest holdings in what is now one of the world’s biggest collections of contemporary and historical tattoo ephemera.

Schiffmacher (now the author of the new Taschen book, TATTOO. 1730s-1970s) realized that tattoos must be documented and preserved by someone with an open mind and vested interest, before they accompanied their recipients to the grave. Many families were ashamed of their loved ones’ interest in skin art, and apt to destroy any evidence of it.

On the other end of the spectrum is a portion of a 19th-century whaler’s arm, permanently emblazoned with Jesus and sweetheart, preserved in formaldehyde-filled jar. Schiffmacher acquired that, too, along with vintage tools, business cards, pages and pages of flash art, and some truly hair raising DIY ink recipes for those jailhouse stick and pokes. (He discusses the whaler’s tattoos in a 2014 TED Talk, below).

His collection also expanded to his own skin, his first canvas as a tattoo artist and proof of his dedication to a community that sees its share of tourists.

Schiffmacher’s command of global tattoo significance and history informs his preference for communicative tattoos, as opposed to obscure ice breakers requiring explanation.

When he first started conceiving of himself as an illustrated man, he imagined the delight any potential grandchildren would take in this graphic representation of his life’s adventures—“like Pippi Longstocking’s father.”

While his Tattoo Museum in Amsterdam is no more, his collection is far from mothballed. Earlier this year, Taschen published TATTOO. 1730s-1970s. Henk Schiffmacher’s Private Collection, a whopping 440-pager the irrepressible 69-year-old artist hefts with pride. You can purchase the book directly via Amazon.

Related Content:

Why Tattoos Are Permanent? New TED Ed Video Explains with Animation

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker, the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and the human alter ego of L’Ourse. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Hear J.S. Bach’s Music Performed on the Lautenwerck, Bach’s Favorite Lost Baroque Instrument

If you want to hear the music of Johann Sebastian Bach played on the instruments that actually existed during the stretch of the 17th and 18th centuries in which he lived, there are ensembles specializing in just that. But a full musical revival isn’t quite as simple as that: while there are baroque cellos, oboes, and violas around, not every instrument that Bach knew, played, and composed for has survived. Take the lautenwerck, a category of “gut-stringed instruments that resemble the harpsichord and imitate the delicate soft timbre of the lute,” according to Baroquemusic.org. Of the “lute-harpsichord” craftsmen in 18th-century Germany remembered by history, one name stands out: Johann Nicolaus Bach.

A second cousin of Johann Sebastian, he “built several types of lute-harpsichord. The basic type closely resembled a small wing-shaped, one-manual harpsichord of the usual kind. It only had a single (gut-stringed) stop, but this sounded a pair of strings tuned an octave apart in the lower third of the compass and in unison in the middle third, to approximate as far as possible the impression given by a lute. The instrument had no metal strings at all.”

This gave the lautenwerck a distinctive sound, quite unlike the harpsichord as we know it today. You can hear it — or rather, a reconstructed example — played in the video above, a short performance of Bach’s Prelude, Fugue, and Allegro in E‑flat, BWV 998 by early-music specialist Dongsok Shin.

“If he owned two of them, they couldn’t have been that off the wall,” Shin says of the composer and his relationship to this now little-known instrument in a recent NPR segment. “The gut has a different kind of ring. It’s not as bright. The lautenwerck can pull certain heartstrings.” Just as the sound of each lautenwerck must have had its own distinctive characteristics in Bach’s day, so does each attempt to recreate it today. “The small handful of artisans currently making lautenwerks are basically forensic musicologists,” notes NPR correspondent Neda Ulaby, “reconstructing instruments based on research and what they think lautenwercks probably sounded like.” As for the one man we can be sure knew them intimately enough to tell the difference, he’d be turning 336 years old right about now.

via NPR

Related Content:

Hear 10 of Bach’s Pieces Played on Original Baroque Instruments

Watch J.S. Bach’s “Air on the G String” Played on the Actual Instruments from His Time

Musicians Play Bach on the Octobass, the Gargantuan String Instrument Invented in 1850

What Guitars Were Like 400 Years Ago: An Introduction to the 9 String Baroque Guitar

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...How Bob Marley Came to Make Exodus, His Transcendent Album, After Surviving an Assassination Attempt in 1976

“The people who are trying to make this world worse aren’t taking a day off. How can I?,” said Bob Marley after a 1976 assassination attempt at his home in Jamaica in which Marley, his wife Rita, manager Don Taylor, and employee Louis Griffiths were all shot and, incredibly, all survived. Which people, exactly, did he mean? Was it Edward Seaga’s Jamaican Labour Party, whose hired gunmen supposedly carried out the attack? Was it, as some even conspiratorially alleged, Michael Manley’s People’s National Party, attempting to turn Marley into a martyr?

Marley had, despite his efforts to the contrary, been closely identified with the PNP, and his performance at the Smile Jamaica Concert, scheduled for two days later, was widely seen as an endorsement of Manley’s politics. When he made his now-famously defiant statement from Island Records’ chief Chris Blackwell’s heavily guarded home, he had just decided to play the concert–this despite the continued risk of being gunned down in front of 80,000 people by the still-at-large killers, or someone else paid by the CIA, whom Taylor and Marley biographer Timothy White claim were ultimately behind the attack.

Marley doesn’t just show up at the concert, he “gives the performance of his lifetime,” notes a brief history of the event, and “closes the show by lifting his shirt, exposing his bandaged bullet wounds to the crowd.” Erroneously reported dead in the press after the shooting, Marley emerged Lazarus-like, a Rastafarian folk-hero. Then he left Jamaica to make his career statement, Exodus, in London — as much a fusion of his righteous political fury, religious devotion, erotic celebration, and peace, love & unity vibes as it is a fusion of blues, rock, soul, funk, and even punk.

It’s a very different album than what had come before in 1976’s Rastaman Vibrations, which was an album of “hard, direct politics” and righteous, “macho” anger, wrote Vivien Goldman, “with surprising specifics like ‘Rasta don’t work for no C.I.A.’” The apotheosis that was 1977’s Exodus begins, however, not with Marley’s previous album but with the Smile Jamaica concert. What was meant to be a brief, one-song, non-aligned appearance became after the shooting “a transcendental 90-minute set for a country being torn apart by internal strife and external meddling,” says Noah Lefevre in the Polyphonic video history at the top. “It was the last show Bob Marley would play in Jamaica for more than a year.”

See the full Smile Jamaica concert above and learn in the Polyphonic video how “six months to the day” later, on June 3, 1977, Marley left on his own exodus and came to record and release what Time magazine named the “album of the century” — the record that would “transform him from a national icon to a global prophet.” On Exodus, he achieves a synthesis of global sounds in a defining creative statement of his major themes. Marley was “really trying to give the African Diaspora a sense of its strength and… unity,” Goldman told NPR on the album’s 30th anniversary, while at the same time, “really embracing, you know, white people, to an extent; doing his best to make a multicultural world work.”

Related Content:

30 Fans Joyously Sing the Entirety of Bob Marley’s Legend Album in Unison

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

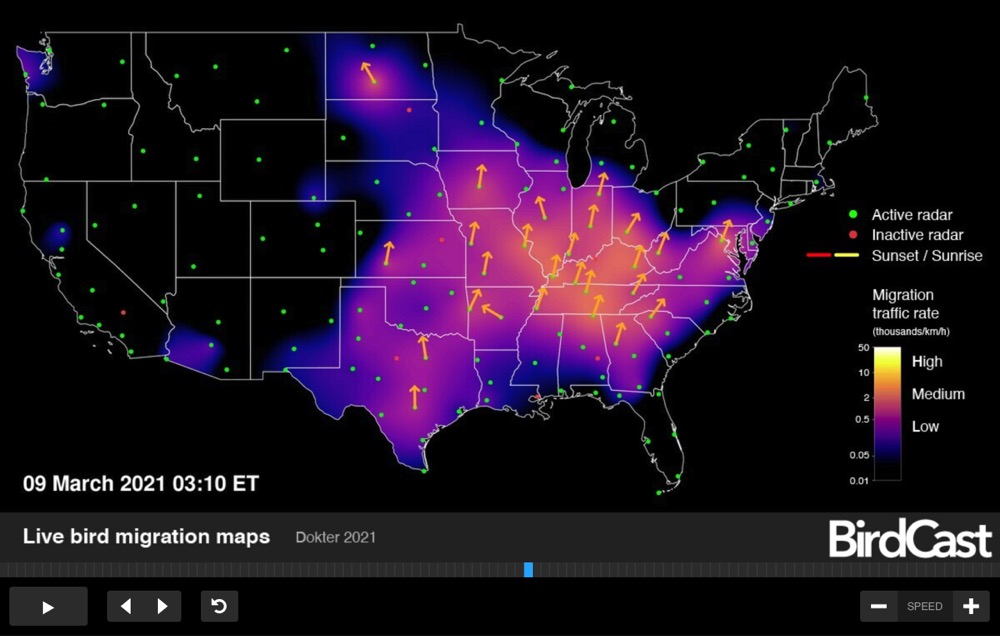

Read More...BirdCast: You Can Now Forecast the Migration of Birds Across the U.S. Just Like the Weather

We talk about the weather more often than we talk about most things, other natural phenomena included. We certainly talk about the weather more often than we talk about birds, much to the disappointment of ornithological enthusiasts. This could be down to the comparative robustness of weather prediction, both as a tradition and as a daily technological presence in our lives. We can hardly avoid seeing the weather forecast, but when was the last time you checked the bird forecast? Such a thing does, in fact, exist, though it’s only come into existence recently, in the form of Birdcast, which provides “real-time predictions of bird migrations: when they migrate, where they migrate, and how far they will be flying.”

Developed by Colorado State University and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, BirdCast offers both live bird migration maps and bird forecast migration maps for the United States. “These forecasts come from models trained on the last 23 years of bird movements in the atmosphere as detected by the US NEXRAD weather surveillance radar network,” says BirdCast’s web site.

Unprecedented in both the kind of information they provide and the detail in which they provide it, “these bird migration maps represented the culmination of a 20-year long vision, so too the beginnings of new inspiration for the next generation of bird migration research, outreach and education, and application.”

You can learn more about the development and workings of BirdCast in the recorded webinar below, featuring research associate Adriaan Dokter and Julia Wang, leader of the Lights Out project, which aims to get Americans spending more time in just such a state. “Every spring and fall, billions of birds migrate through the US, mostly under the cover of darkness,” says its section of BirdCast’s site. “This mass movement of birds must contend with a dramatically increasing but still largely unrecognized threat: light pollution.” The goal is “turning off unnecessary lighting during critical migration periods,” and with spring having begun last weekend, we now find ourselves in just such a period. Luckily, our fine feathered friends shouldn’t be disturbed by the glow of the BirdCast map on your screen. View live BirdCast maps here.

via Kottke

Related Content:

What Kind of Bird Is That?: A Free App From Cornell Will Give You the Answer

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Hear Marianne Faithfull’s Three Versions of “As Tears Go By,” Each Recorded at a Different Stage of Life (1965, 1987 & 2018)

When a 17-year-old Marianne Faithfull finished the final take of her 1965 hit “As Tears Go By” — penned by a young duo of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards as one of their first original songs — Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham “came and gave me a big hug,” she recalled “‘Congratulations darling. You’ve got yourself a number six,’ he said.”

Richards remembered the song in his autobiography as “a terrible piece of tripe” and “money for old rope,” but it actually peaked at number 22 on the Billboard Hot 100, where it stayed for nine weeks, no small thing. So popular was “As Tears Go By” that the Stones themselves recorded a version the following year. Their take also entered the Hot 100, where it peaked at number six.

The story of the song represents in brief the evolution of its original singer. Fated in her early years to be known as little more than Jagger’s muse, an image she grew to hate, Faithfull went from hanger-on in the sixties, “an essential component of the Swinging London scene,” writes reviewer alrockchick; to a homeless heroin addict; to a legend revived, her “whiskey-soaked” croak of a voice the perfect vehicle for delivering smoke-filled tales of weariness and betrayal.

Along the way, there was “As Tears Go By,” a song Faithfull came to embody, though she didn’t think much of it as a teenager. (See Brian Epstein introduce her on Hulabaloo, above, in 1965.)

She was “never that crazy” about it, she said. “God knows how Mick and Keith wrote it or where it came from…. In any case, it’s an absolutely astonishing thing for a boy of 20 to have written a song about a woman looking back nostalgically on her life.”

The “boys” had help — at first they cribbed the title “As Time Goes By” from the famous tearjerker in Casablanca. According to Loog Oldham, he locked the two Stones in a room together and said, “I want a song with brick walls all around it, high windows and no sex.” How that became a Marianne Faithfull signature is something of a mystery. At times she claimed Jagger wrote the song for her; at others, she emphatically denied it. But as the contrast between her voice and the song’s saccharine, maudlin nature changed, so too did the power of her delivery, which is not to say her first recording didn’t warrant the attention.

“The voice on ‘As Tears Go By’ and ‘Summer Nights,’” altrockchick writes, “has an airy, surreal quality; the voice on Broken English,” her 1979 comeback (which does not include “As Tears Go By”), “is as real as it gets” and only got more real with time. In a Nico-esque monotone drone, she revisited the song she made famous in the mid-sixties in the 1987 take above for the album Strange Weather. She had just recently gotten clean and lost a lover to suicide.

The weathered vulnerability she projects is worlds away from the dreamy melancholy of the past, her voice “a far cry from the 60s sweetness,” The Music Aficionado blog notes. “Years of substance abuse and constant smoking dropped her pitch and made it raspy.” These qualities are even more pronounced in a 2018 version of the song from the album Negative Capability. It functions almost as a coda for a career as an interpreter of the songs of others, though she’s written no few of her own (and may yet release another version of “As Time Goes By.”)

She is remembered for much more than her first hit, but Faithfull’s revisitation of “As Tears Go By” over the years seems to speak to an ambivalent acceptance of Mick Jagger’s constant presence in her story — and a graceful, if not exactly uplifting, acceptance of the inevitable ravages of age and fame.

You can hear her very recent interview on the Broken Record podcast below:

Related Content:

Jean-Luc Godard Shoots Marianne Faithfull Singing “As Tears Go By” (1966)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Four Cellists Play Ravel’s “Bolero” on One Cello

And now for something completely different…

Above, the Wiener Celloensemble 5 + 1–“an untraditional cello ensemble” founded by the Vienna Philharmonic’s Gerhard Kaufmann–presents an unconventional performance of Ravel’s “Bolero.” It’s minimalist, in a certain way. Four musicians. One instrument. And nothing more…

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

via ClassicFM/MyModernMet

Related Content:

Hear a 1930 Recording of Boléro, Conducted by Ravel Himself

Copenhagen Philharmonic Plays Ravel’s Bolero at Train Station

Read More...Women Street Photographers: The Web Site, Instragram Account & Book That Amplify the Work of Women Artists Worldwide

It’s almost impossible not to wonder how reclusive artists of the past — like anonymous street photographer and Chicago nanny Vivian Maier — would fare in the age of Tumblr and Instagram. Would Maier have become internet famous? Would she have posted any of her photographs? The little we know about her makes it hard to answer the question. Maier lived a life of abstemious self-negation. “She never exhibited her work,” Alex Kotlowitz writes at Mother Jones, “she didn’t share her photos with anyone, except some of the children in her care.”

And yet, Maier was known to enjoy conversations about film and theater with knowledgeable people. One suspects that if she had been able to stay in touch with like minds, she might have been encouraged by a supportive community she couldn’t find anywhere else. We might imagine her, for example, submitting a select few photographs to Women Street Photographers, a project that began in 2017 as an Instagram account and has since “burgeoned into a website, artist residency, series of exhibitions, film series, and now a book published this month by Prestel,” Grace Ebert writes at Colossal.

For women street photographers living and working today, the project offers what founder Gulnara Samoilova says she needed and couldn’t find: “I soon began to realize that with this platform, I could create everything I had always wanted to receive as a photographer: the kinds of support and opportunities that would have helped me grow during those formative and pivotal points on my journey.” The project is international in scope, bringing together the work of 100 women from 31 countries, “a tiny sampling of what’s out there.”

In her introduction to the 224-page book, Samoilova describes the importance of such a collection:

Street photography is both a record of the world and a statement of the artist themselves: it is how they see the world, who they are, what captures their attention, and fascinates them. There’s a wonderful mixture of art and artifact, poetry and testimony that makes street photography so appealing. It’s both documentary and fine art at the same time, yet highly accessible to people outside the photography world.

There are Vivian Maiers around the world driven to document their surroundings, whether anyone ever sees their work or not. Maier made her photographs “for all the right reasons,” says Chicago artist Tony Fitzpatrick. “She made them because to not make them was impossible. She had no choice.” But perhaps she might have chosen to show her work if she had access to platforms like Women Street Photographers. We can be grateful for such outlets now: they offer perspectives that we can find nowhere else. Women Street Photographers will announce the winners of its inaugural virtual exhibition “on or around April 1.”

via Colossal

Related Content:

Meet Gerda Taro, the First Female Photojournalist to Die on the Front Lines

Take a Visual Journey Through 181 Years of Street Photography (1838–2019)

Vivian Maier, Street Photographer, Discovered

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Online Degrees & Mini Degrees: Explore Masters, Mini Masters, Bachelors & Mini Bachelors from Top Universities

Explore a collection of online Degree and Mini Degree Programs from major universities, including MIT, Harvard, UC Berkeley & more.

The lists below include Online Mini Master’s Degrees, Online Master’s Degrees, Online Mini Bachelor’s Degrees, and finally Online Bachelor’s Degrees.

Many of these programs are offered at a significantly lower price than traditional degree programs.

Mini Master’s Programs

To learn more about the value of MicroMasters programs from edX, and MasterTrack Certificate programs from Coursera, read this article from Business Insider.

Business

- Accounting — Indiana University via edX

- Business Leadership — The University of Queensland via edX

- Business Management — Indian Institute of Management Bangalore via edX

- Business and Operations for a Circular Bio-Economy — Wageningen University & Research via edX

- Certified Lifestyle Medicine Executive — Doane University via edX

- Corporate Innovation — The University of Queensland via edX

- Design Thinking - Rochester Institute of Technology via edX

- Digital Leadership — Boston University via edX

- Digital Product Management — Boston University via edX

- Entrepreneurship — Indian Institute of Management Bangalore via edX

- Finance — MIT via edX

- Finance, Analysis and Modeling — Macquarie via Coursera

- Global Business Leadership and Management — Arizona State via edX

- Global Leadership and Human Resource Management - Macquarie Business School via Coursera

- Healthcare Administration — Doane University via edX

- Innovation & Entrepreneurship — Tecnológico de Monterrey via edX

- Innovation Management & Entrepreneurship — HEC via Coursera

- International Hospitality Management — The Hong Kong Polytechnic University via edX

- Leadership in Global Development — The University of Queensland via edX

- MBA Core Curriculum — University of Maryland via edX

- Managing Technology & Innovation: How to deal with disruptive change — RWTH Aachen University via edX

- Marketing Analytics — UC Berkeley via edX

- Marketing in a Digital World — Curtin University via edX

- Principles of Manufacturing — MIT via edX

- Project Management — Rochester Institute of Technology via edX

Computer Science

- AI and Machine Learning — Arizona State University via Coursera

- Blockchain Applications — Duke University via Coursera

- Cloud Computing — University of Maryland via edX

- Cybersecurity — Rochester Institute of Technology via edX

- Cybersecurity- Arizona State University via Coursera

- Industrial Internet of Things — UC Boulder via Coursera

- Information Systems — Indiana University via edX

- Internet of Things (IoT) — Curtin University via edX

- Machine Learning for Analytics- U Chicago via edX

- Nanoscience and Technology — Purdue University via edX

- Predictive Analytics using Python — The University of Edinburgh via edX

- Quantum Technology: Computing — Purdue University via edX

- Quantum Technology: Detectors and Networking — Purdue University via edX

- Software Development — The University of British Columbia via edX

- Software Engineering - Arizona State University via Coursera

- Supply Chain Management — MIT via edX

- Supply Chain Excellence — Rutgers University via Coursera

Data Science

- Algorithms and Data Structures — UC San Diego via edX

- Analytics: Essential Tools and Methods — Georgia Tech via edX

- Big Data — University of Adelaide via edX

- Big Data — Arizona State University via Coursera

- Data Analytics for Managers — Tufts University via Coursera

- Data Science — UC San Diego via edX

- Statistics and Data Science — MIT via edX

Education

- Instructional Design- University of Illinois via Coursera

- Instructional Design and Technology — University of Maryland via edX

- Leading Educational Innovation and Improvement — University of Michigan via edX

Engineering

- Construction Engineering and Management — University of Michigan via Coursera

- Reliability and Decision Making in Engineering Design — Purdue University via edX

- Solar Energy Engineering - Delft University of Technology via edX

- Structural Design — Purdue University via edX

Health

- Health Informatics - Yale University via Coursera

- Water and Global Human Health — Queen’s University via edX

Humanities/Arts & Culture

- Humanities & Soft Skills — Tecnológico de Monterrey via edX

- Integrated Digital Media — NYU via edX

- English Proficiency for Graduate Studies Certificate — Arizona State University via Coursera

- Writing for Performance and the Entertainment Industries - Cambridge University via edX

Sustainability

- Economics and Policies for a Circular Bio-Economy — Wageningen University & Research via edX

- Emerging Automotive Technologies — Chalmers University via edX

- Sustainable Agribusiness — Doane University via edX

- Sustainable Energy — The University of Queensland via edX

- Sustainability and Development — University of Michigan via Coursera

UX Design

- UX Design — University of Minnesota via Coursera

- UX Design and Evaluation — HEC Montréal via edX

Sundry

- Chemistry and Technology for Sustainability — Wageningen University & Research via edX

- International Law - Université catholique de Louvain via edX

- Social Work: Practice, Policy and Research — University of Michigan via Coursera

Online Master’s Degrees

Business

- Online Master’s of Accounting (iMSA) — University of Illinois via Coursera

- Master’s Degree in Accounting — Indiana University via edX

- Master of Business Administration (iMBA) — University of Illinois via Coursera

- Online MBA Degree: Master of Business Administration — Boston University via edX

- Global Master of Business Administration (GMBA) — Macquarie University via Coursera

- MSc in Innovation and Entrepreneurship — HEC via Coursera

- Master’s Degree in Leadership: Service Innovation — The University of Queensland via edX

- Master of Science in Management — University of Illinois via Coursera

- Master’s Degree in Supply Chain Management — Arizona State via edX

Computer Science & Electrical Engineering

- Master’s Degree in Analytics — Georgia Tech via edX

- Master’s Degree in Computer Science - UT Austin via edX

- Master of Computer and Information Technology — University of Pennsylvania

- Master of Computer Science — Arizona State via Coursera

- Master of Computer Science (Featuring Data Science Track) — University of Illinois via Coursera

- Master’s Degree in Cybersecurity — Georgia Tech via edX

- Master’s Degree in IT Management — Indiana University via edX

- Master of Science in Electrical Engineering — UC Boulder via Coursera

- Master’s Degree in Electrical and Computer Engineering — Purdue University via edX

- Master of Machine Learning and Data Science - Imperial College London via Coursera

Data Science

- Master of Applied Data Science — University of Michigan via Coursera

- Master’s Degree in Data Science — UT-Austin via edX

- Master of Science in Data Science — UC Boulder via Coursera

Public Health

- Master of Public Health — University of Michigan via Coursera

- Global Master of Public Health (GMPH) — Imperial College London via Coursera

- Master of Science in Population and Health Sciences — University of Michigan via Coursera

Sundry

- Master’s Degree in Civil Engineering — Purdue University via edX

- Master’s Degree in Nutritional Sciences — UT-Austin via edX

- Master’s Degree in Mechanical Engineering — Purdue University via edX

Micro Bachelor’s Degrees

- Business Analytics Foundations - Southern New Hampshire University via edX

- Business and Professional Communication for Success — Doane University via edX

- Computer Science Fundamentals — NYU via edX

- Cybersecurity Fundamentals — NYU via edX

- Data Management with Python and SQL - Southern New Hampshire University via edX

- Elements of Data Science — Rice University via edX

- Introduction to Databases — NYU via edX

- Introduction to Information Technology — Western Governors University via edX

- Marketing Essentials — Doane University via edX

- Professional Writing — Arizona State via edX

- Programming & Data Structures — NYU via edX

Bachelor’s Degrees

- Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences — University of North Texas via Coursera

To explore a list of free courses, see our collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

Read More...Michael Winslow, the “Man of 10,000 Sound Effects”, Impersonates the Sounds of Jimi Hendrix’s and Led Zeppelin’s Electric Guitars with His Voice

Even if you weren’t a huge fan of the Police Academy movies, there was one character that made them watchable: Larvell Jones, played by Michael Winslow, “The Man of a 10,000 Sound Effects.” His character is a sort of oddball presence throughout the series, whose ability to sound like a siren, a machine gun, a guard dog, or any number of things, invariably helps his team save the day. He’s been the only consistent character through all eight entries of the movie series, a brief television spin-off, and an animated cartoon series. And I dare say he’s the franchise’s reason to exist, as a Police Academy without Larvell Jones would be…what? A bunch of crappy cops?

And while you might think of him as a master of machine noises, Winslow is actually a very musical performer, as his above impression of Jimi Hendrix, both vocals and guitar, proves. Winslow was an army brat, moved all over the place, and his imitation skills developed at an early age, a coping mechanism for a lonely childhood. He kept at it, and made it onto The Gong Show in 1978. The prize money allowed him to stay in Los Angeles and start making the club rounds. He got scouted for Police Academy while opening for the Count Basie Orchestra, performing “some fusion jazz sounds,” as he described it in an interview. Fortunately, the filmmakers let him improvise through his scenes and his career took off from there.

As the clips here show, Winslow can jam hard. His Hendrix impression is a little bit stoned, and he gets the voice right. With a backing band on tape, he goes on to provide the vocals and the distorted, flanged guitar. You can see that little has changed from the version from the ‘80s at the Just for Laughs Comedy Festival in Montreal, Canada, and a 2011 performance from the Dubomedy International Performing Arts Festival in Dubai. The latter has better sound quality and separation so you can hear Winslow’s work.

His Led Zeppelin impression combines both Robert Plant and Jimmy Page, and I won’t spoil the joke, but Winslow explains how Plant came up with “Immigrant Song.”

And there’s no sound effects involved in his Tina Turner impression, but a good wig, and an impressive set of pipes that only get wobbly a few times. But then again, so do his legs.

Side note: Before Winslow there was a comedian called Wes Harrison, who had a similar talent and a similar rise to stardom: from talent show winner to a regular guest on late night shows in the 1960s to a steady stream of nightclub appearances.

In 1988, the two men, separated by 35 years, performed together on a Dick Clark variety show. It is perhaps the only time the two shared a stage.

Related Content:

How the Sound Effects on 1930s Radio Shows Were Made: An Inside Look

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

Read More...