Google Data Analytics Certificate: 8 Courses Will Help Prepare Students for an Entry-Level Job in 6 Months

During the pandemic, Google launched a series of Career Certificates that will “prepare learners for an entry-level role in under six months.” The new career initiative includes certificates concentrating on Project Management and UX Design. And now also Data Analytics, a burgeoning field that focuses on “the collection, transformation, and organization of data in order to draw conclusions, make predictions, and drive informed decision making.”

Offered on the Coursera platform, the Data Analytics Professional Certificate consists of eight courses, including “Foundations: Data, Data, Everywhere,” “Prepare Data for Exploration,” “Data Analysis with R Programming,” and “Share Data Through the Art of Visualization.” Overall this program “includes over 180 hours of instruction and hundreds of practice-based assessments, which will help you simulate real-world data analytics scenarios that are critical for success in the workplace. The content is highly interactive and exclusively developed by Google employees with decades of experience in data analytics.”

Upon completion, students–even those who haven’t pursued a college degree–can directly apply for jobs (e.g., junior or associate data analyst, database administrator, etc.) with Google and over 130 U.S. employers, including Walmart, Best Buy, and Astreya. You can start a 7‑day free trial and explore the courses here. If you continue beyond the free trial, Google/Coursera will charge $39 USD per month. That translates to about $235 after 6 months, the time estimated to complete the certificate.

Explore the Data Analytics Certificate by watching the video above. Learn more about the overall Google career certificate initiative here. And find other Google professional certificates here.

Note: Open Culture has a partnership with Coursera. If readers enroll in certain Coursera courses and programs, it helps support Open Culture.

Related Content:

Read More...ABBA Set to Release Their First Album in 40 Years: Hear Two New Tracks, and Get a Glimpse of Their Digital Live Show

45 years ago, ABBA’s music was inescapable. 25 years ago, it had become a seemingly unwelcome reminder of the inanities of the 1970s in general and the days of disco in particular. But now, it’s revered: rare is the 21st-century music critic who absolutely refuses to acknowledge the Swedish foursome’s mastery of pure pop songwriting and studio production. With current musicians, too, naming ABBA among their inspirations without embarrassment, the time has surely come for ABBA themselves to return to the spotlight — a spotlight that first illuminated them for the world in 1974, when their performance of “Waterloo” won the Eurovision Song Contest.

ABBA’s streak lasted until the early 1980s, ending in a hiatus that ultimately stretched out to some 40 years. Pop culture has changed quite a bit in that time, but technology much more so. The band have thus put together a thoroughly modern comeback involving not just a new album, but also a live show starring computer-generated versions of members Björn Ulvaeus, Benny Andersson, Agnetha Fältskog, and Anni-Frid Lyngstad — “Abbatars,” as Ulvaeus calls them.

Beginning next year, they’ll play ABBA’s hits in a custom-built 3,000-seat arena in London’s Olympic park, engineered to accompany each song with their own elaborate light show. Animated with motion-captured performances by the real ABBA, their appearance has been modeled after the way the band looked in the 1970s (if not quite the way they dressed).

Titled Voyage, this digital ABBA experience will open in 2022, thus solving the problem of touring that had long discouraged a reunion. “We would like people to remember us as we were,” Ulvaeus said in the late 2000s. “Young, exuberant, full of energy and ambition.” But with all four now-septuagenarian members still alive and able to make music, remaining wholly inactive seems to have started feeling like a shame. They made their return to the studio in 2018, recording the new songs “I Still Have Faith in You” and “Don’t Shut Me Down,” both of which will appear on the new album, also called Voyage, coming out in November. All this will bring back memories for longtime fans, as well as provide a thrilling experience for their many listeners too young to have experienced an ABBA show or album release before. But I can’t be the only member of my generation wondering if, twenty years from now, we’ll be buying tickets for a digitally re-created Ace of Base.

Related Content:

How ABBA Won Eurovision and Became International Pop Stars (1974)

Listen to ABBA’s “Dancing Queen” Played on a 1914 Fairground Organ

This Man Flew to Japan to Sing ABBA’s “Mamma Mia” in a Big Cold River

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Watch Lost Studio Footage of Brian Wilson Conducting “Good Vibrations,” The Beach Boys’ Brilliant “Pocket Symphony”

After Brian Wilson created what Hendrix called the “psychedelic barbershop quartet” sound of the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, he moved on to what he promised would be another quantum leap beyond. “Our new album,” Smile, he claimed, “will be as much an improvement over Sounds as that was over Summer Days.” But in his pursuit to almost single-handedly surpass the Beatles in the art of studio perfectionism, Wilson overreached. He famously scrapped the Smile sessions, and instead released the hastily-recorded Smiley Smile to fulfill contract obligations in 1967.

Smiley Smile’s peculiar genius went unrecognized at the time, particularly because its centerpiece, “Good Vibrations,” had set expectations so high. Recorded and released as a single in 1966, the song would be referred to as a “pocket symphony” (a phrase invented either by Wilson himself or publicist Derek Taylor). Even the jaded session players who sat in for the hours of recording — veterans from the famed “Wrecking Crew” — knew they were making something that transcended the usual rut of pop simplicity.

“We were doing two, three record dates a day,” says organ player Mike Melvoin, “and the level of sophistication was, like, not really sophisticated at all.” The “Good Vibrations” sessions were another experience entirely. “All of a sudden, you walk in, and here’s run-on songs. It’s like this section followed by that section followed by this section, and each of them with a completely different character. And you’re going, ‘Whoa.’” Wrecking Crew bassist Carol Kay, who sat in for the sessions but didn’t make the final mix, remembers thinking, “that wasn’t your normal rock ‘n’ roll…. You were part of a symphony.”

Wilson’s pop symphonies were created and arranged not on paper but during the recording sessions themselves, which accounted for the 90 hours of tape and tens of thousands of dollars in expenses, the most money ever spent on a pop single. He made creative decisions according to what he called “feels,” fragments of melody and sound that formed his avant-garde pastiches. “Each feel represented a mood or an emotion I’d felt,” he recalled, “and I planned to fit them together like a mosaic.” Not everyone could see the plan at first.

But when Wilson finally emerged from months of isolation after cutting and mixing hours and hours of tape, the rest of the band was “very blown out,” he says. “They were most blown out. They said, ‘Goddamn, how can you possibly do this, Brian?’ I said, ‘Something got inside of me.’… They go, ‘Well, it’s fantastic.’ And so they sang really good just to show me how much they liked it.” In the edited footage at the top, taken over the six months of recording in four different studios, you can see drummer Hal Blaine, organ player Mick Melvoin, double bass player Lyle Ritz, and the Beach Boys themselves all recording their parts.

To the press, Wilson told one story — “Good Vibrations” was “still sticking pretty close to that same boy-girl thing, you know, but with a difference. And it’s a start, it’s definitely a start.” But the song — which he first wanted to call “Good Vibes” — is very much meant to suggest “the healthy emanations that should result from psychic tranquility and inner peace,” wrote Bruce Golden in The Beach Boys: Southern California Pastoral. In that sense, “Good Vibrations” was aspirational, almost tragically so, for Wilson, who could not fulfill its promises. Yet, in another sense, “Good Vibrations” is itself the fulfillment of Wilson’s creative promise, an eternally brilliant “pocket symphony” — and as Wilson told engineer Chuck Britz during the sessions, his “whole life performance in one track.”

Related Content:

How the Beach Boys Created Their Pop Masterpieces: “Good Vibrations,” Pet Sounds, and More

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Two Haruki Murakami Stories Adapted into Short Films: Watch Attack on a Bakery (1982) and A Girl, She Is 100% (1983)

At this year’s Cannes Film Festival, the Award for Best Screenplay went to Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car, an adaptation of a story by Haruki Murakami. So did FIPRESCI Prize, the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury, and no small amount of critical acclaim, suggesting that the code for translating Murakami onto the screen might finally have been cracked. Every now and again over the past forty years, a bold filmmaker has taken on the challenge of turning a work of that most world-famous Japanese novelist into a feature. But until recently, the results have for the most part not been received as especially consequential in and of themselves.

In general, short fiction tends to produce more satisfying adaptations than full-fledged novels, and Murakami’s work seems not to be an exception (as underscored a few years ago by Korean auteur Lee Chang-dong’s Burning). Hamaguchi’s film spins some 40 pages into a running time of nearly three hours, doing the opposite of what other Japanese filmmakers have done with Murakami’s short stories. In 1982, Naoto Yamakawa made one of them into Attack on a Bakery, a short film running less than twenty minutes; the following year, he made another into the even shorter A Girl, She is 100%, running less than fifteen. Today Murakami fans everywhere can watch them both on Youtube, complete with English subtitles.

The material will feel familiar to English-language Murakami readers. A main character of the story “The Second Bakery Attack” reminisces about a robbery he attempted as a hungry young man that went comically off the rails, in a manner similar to the one in Yamakawa’s first short. (In 2010 “The Second Bakery Attack,” wherein the now-married narrator robs a fast-food joint with his new bride, itself became a short film directed by Carlos Cuarón, brother of Alfonso.) Though “The Bakery Attack” has never been officially published in English, “On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning” has, and it now stands as one of Murakami’s representative short works in that language; it also, in the original, provides the basis for A Girl, She Is 100%.

“She doesn’t stand out in any way,” Murakami’s narrator says of the titular figure. “Her clothes are nothing special. The back of her hair is still bent out of shape from sleep. She isn’t young, either — must be near thirty, not even close to a ‘girl,’ properly speaking. But still, I know from fifty yards away: She’s the 100% perfect girl for me.” Yamakawa dramatizes a similar fleeting encounter and the romantic speculations that resonate in the man’s mind. Like the half-baked philosophical and political convictions of the would-be robbers, these inspire the director to the kind of visual and formal inventiveness one would expect given his background in Godard and Scorsese scholarship. But the only filmmaker name-checked is Woody Allen, which fans will recognize as a characteristic Murakami reference. So as are the inclusions of Wagner, D.H. Lawrence, jazz music — and of course, an unexpected cat.

Related Content:

Read 12 Stories By Haruki Murakami Free Online

Haruki Murakami’s Passion for Jazz: Discover the Novelist’s Jazz Playlist, Jazz Essay & Jazz Bar

A 3,350-Song Playlist of Music from Haruki Murakami’s Personal Record Collection

Memoranda: Haruki Murakami’s World Recreated as a Classic Adventure Video Game

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

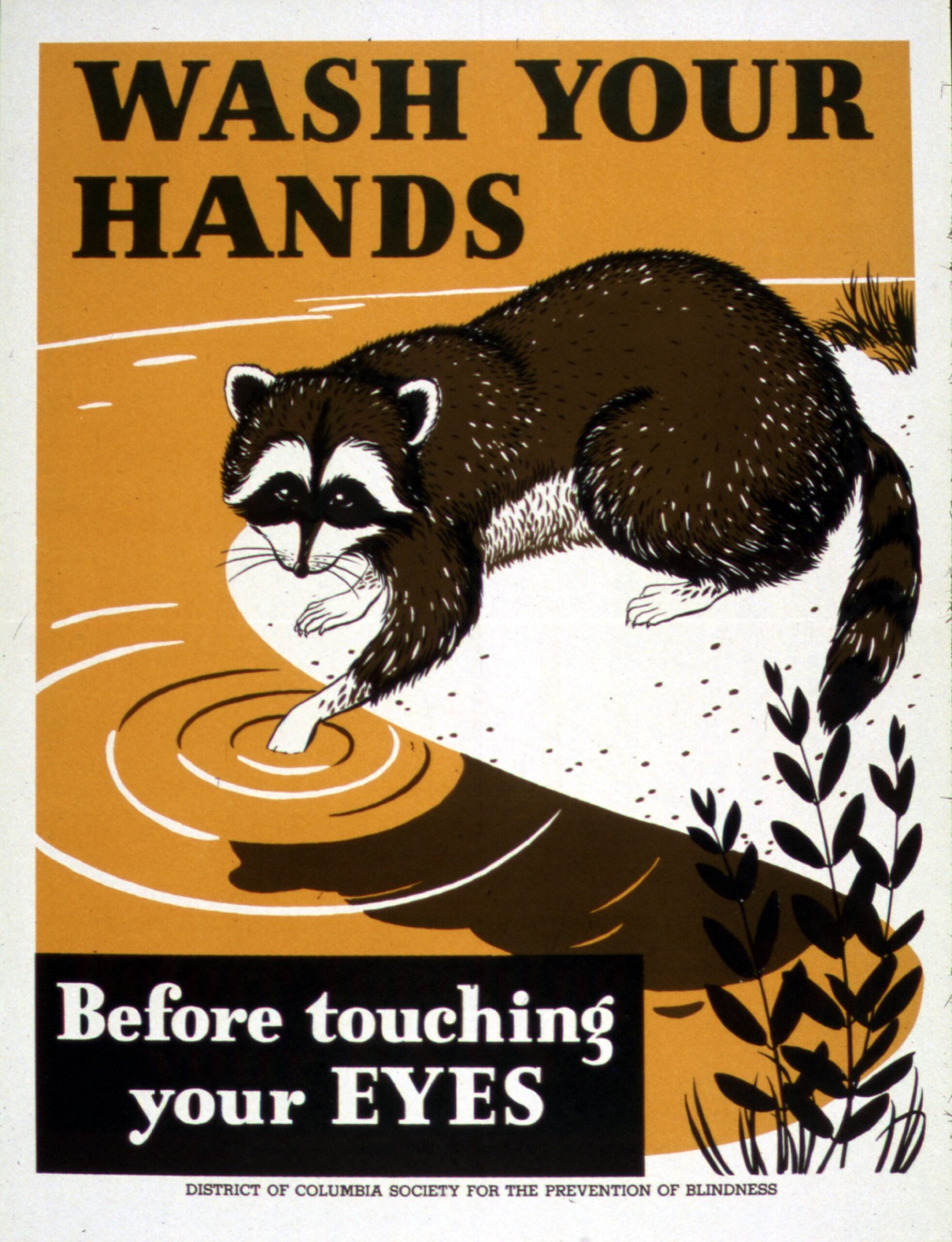

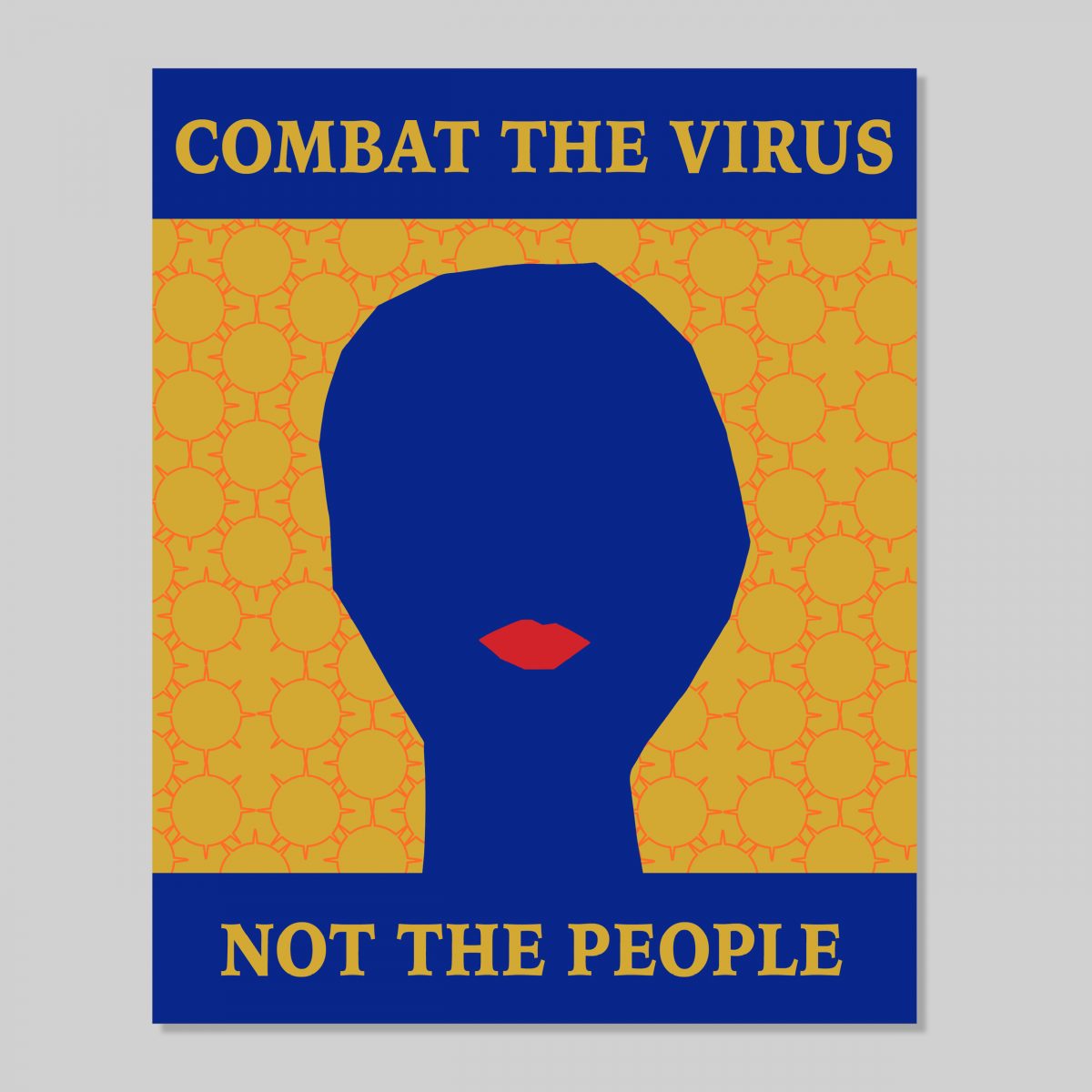

Read More...Vintage Public Health Posters That Helped People Take Smart Precautions During Past Crises

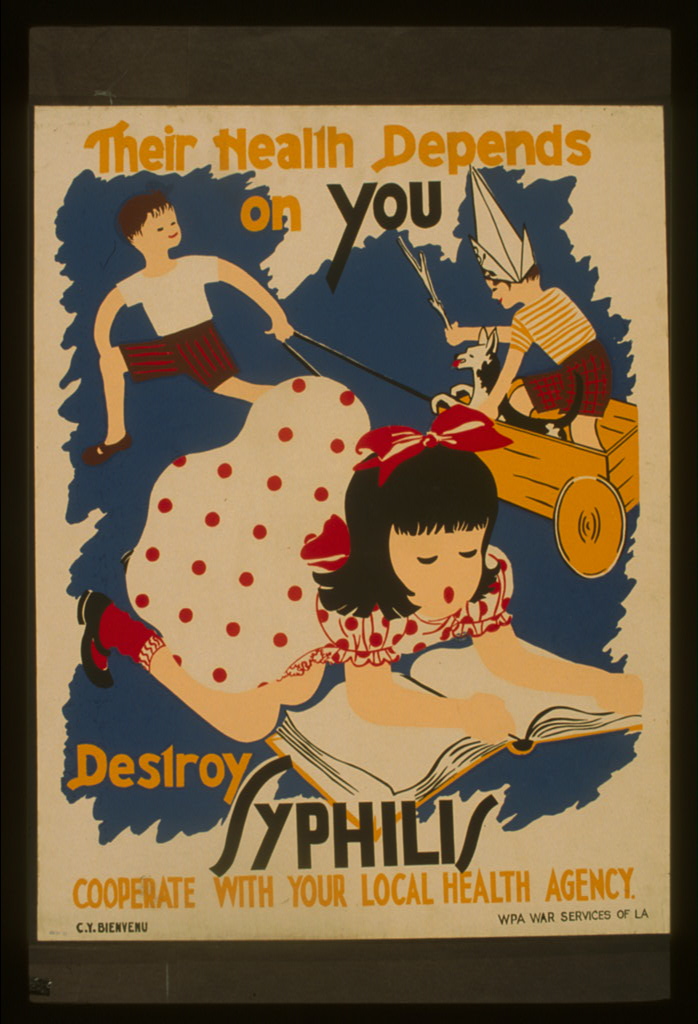

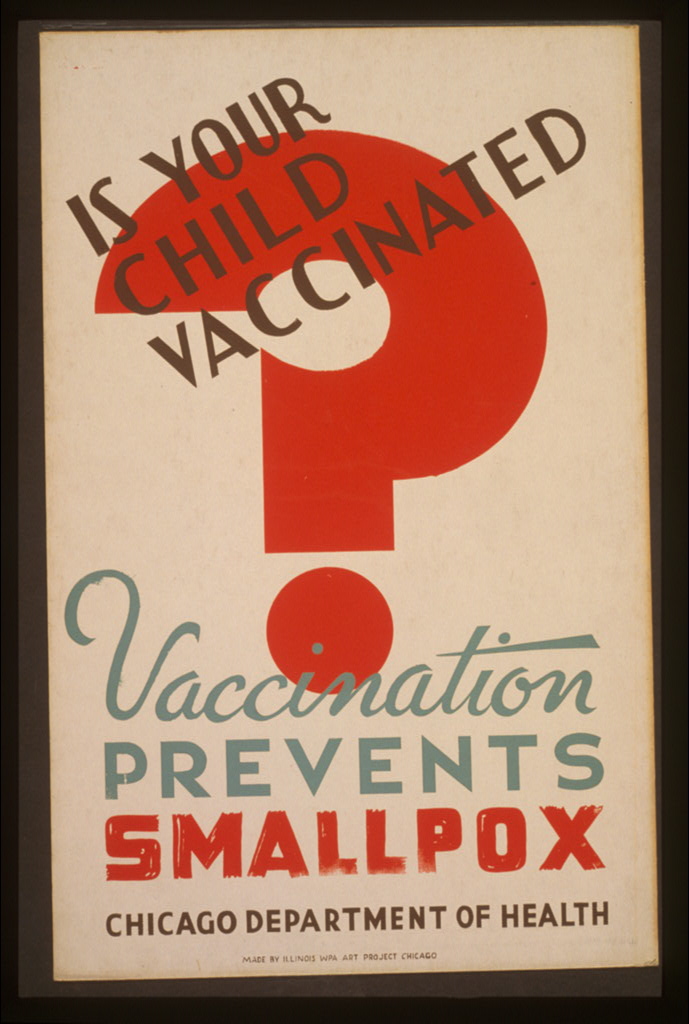

We subscribe to the theory that art saves lives even in the best of times.

In the midst of a major public health crisis, art takes a front line position, communicating best practices to citizens with eye catching, easy to understand graphics and a few well chosen words.

In March of 2020, less than 2 weeks after COVID-19 brought New York to its knees, Angelina Lippert, the Chief Curator of Poster House, one of the city’s newer museums shared a blog post, considering the ways in which the CDC’s basic hygiene recommendations for helping stop the spread had been touted to previous generations.

As she noted in a lecture on the history of the poster as Public Service Announcement the following month, “mass public health action… is how we stopped tuberculosis, polio, and other major diseases that we don’t even think of today:”

And a major part of eradicating them was educating the public. That’s really what PSAs are—a means of informing and teaching the public en masse. It goes back to that idea … of not having to seek out information, but just being presented with it. Keeping the barrier for entry low means more people will see and absorb the information.

The Office of War Information and the District of Columbia Society for the Prevention of Blindness used an approachable looking raccoon to convince the public to wash hands in WWII.

Artist Seymour Nydorf swapped the raccoon for a blonde waitress with glamorous red nails in a series of six posters for the U.S. Public Health Service of the Federal Security Agency

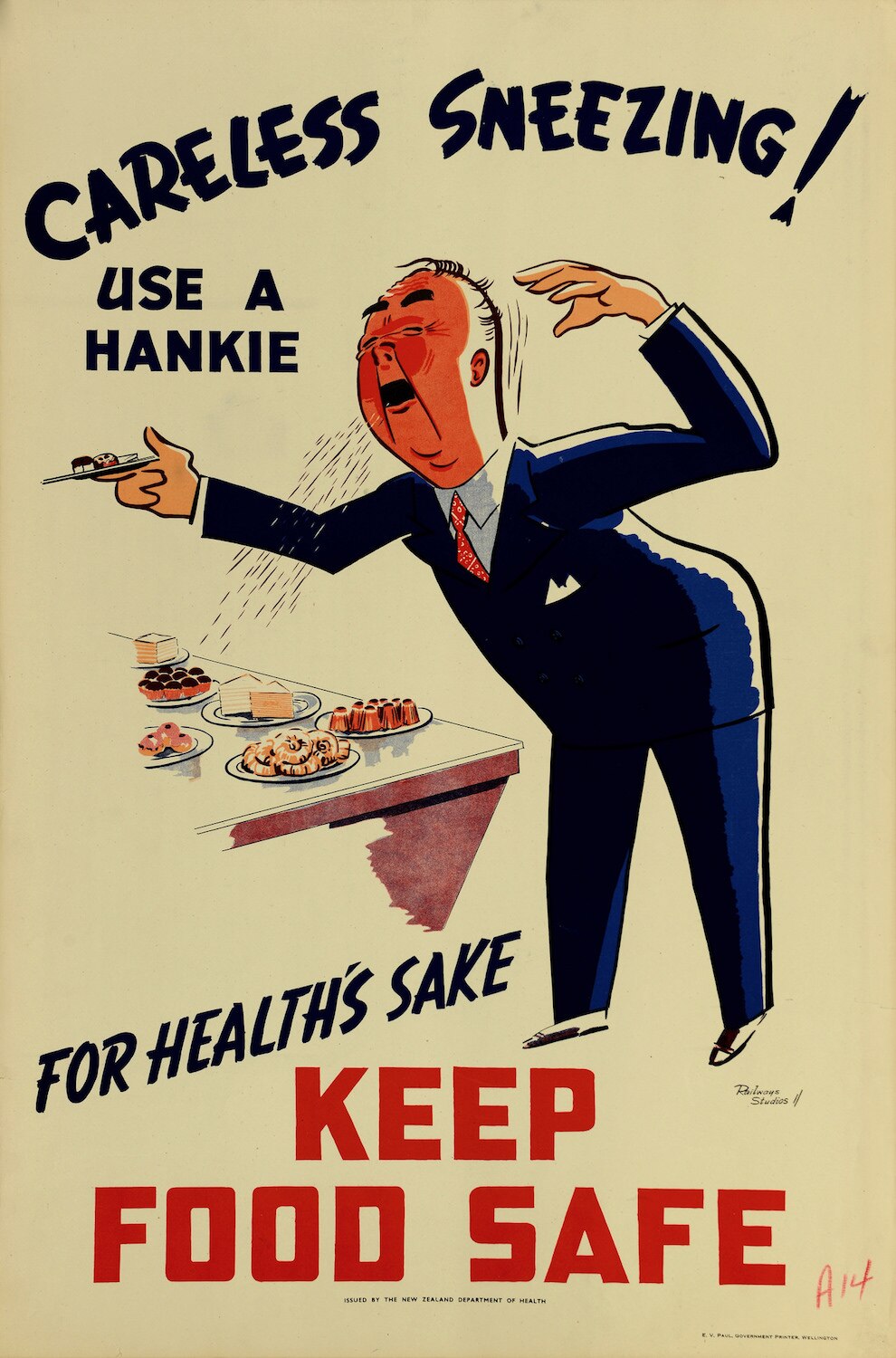

Coughing and sneezing took posters into somewhat grosser terrain.

The New Zealand Department of Health’s 50s era poster shamed careless sneezers into using a hankie, and might well have given those in their vicinity a persuasive reason to bypass the buffet table.

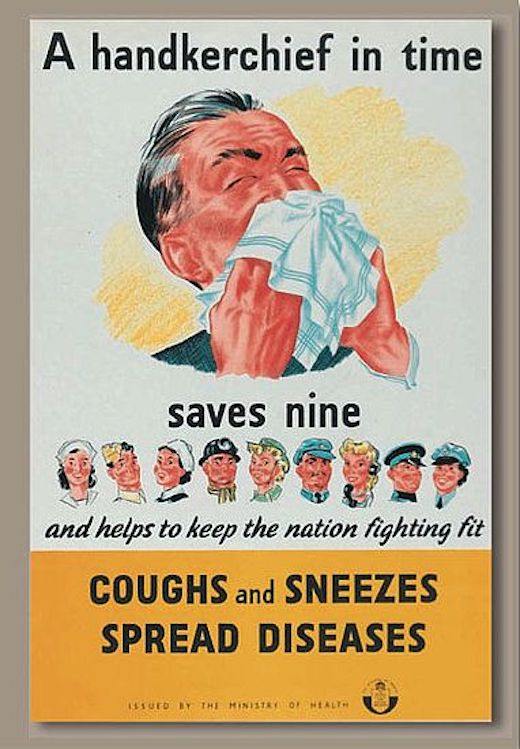

Great Britain’s Central Council for Health Education and Ministry of Health collaborated with

Her Majesty’s Stationery Office to teach the public some basic infection math in WWII.

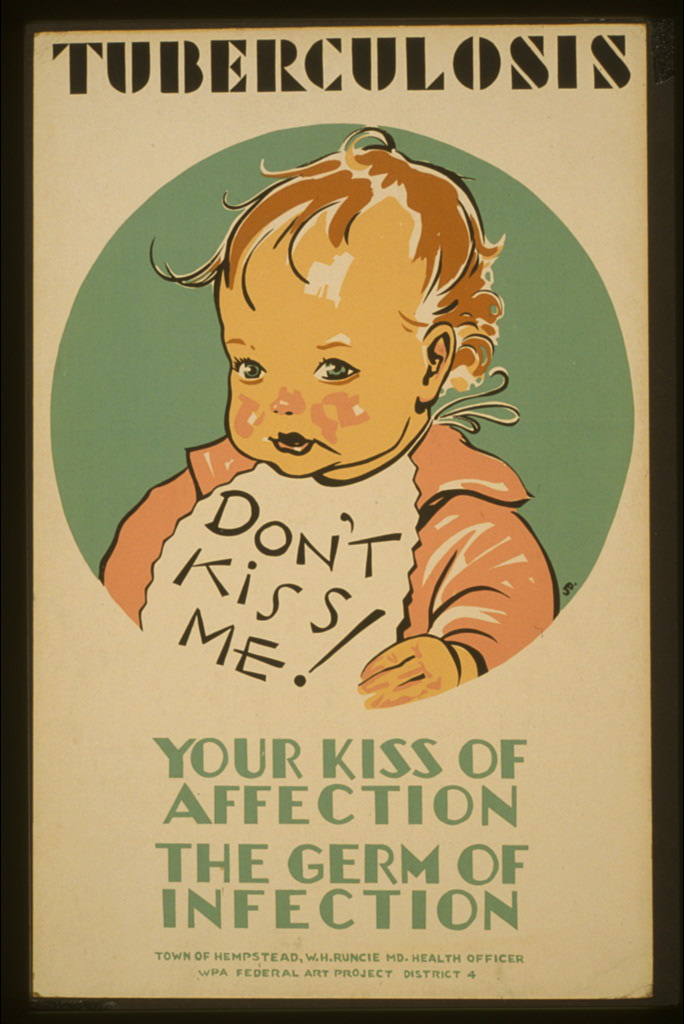

Children’s wellbeing can be a very persuasive tool. The WPA Federal Art Project was not playing in 1941 when it paired an image of a cherubic tot with stern warnings to parents and other family members to curb their affectionate impulses, as well as the transmission of tuberculosis.

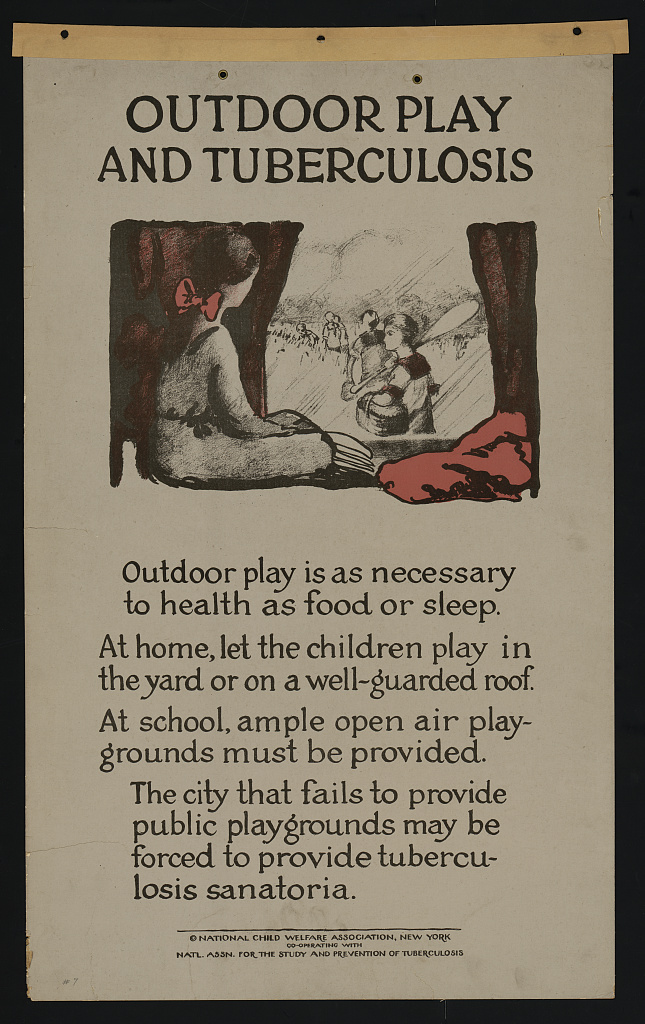

The arresting image packs more of a wallop than this earnest and far wordier, early 20s poster by the National Child Welfare Association and the National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis.

Read Poster House Chief Curator Angelina Lippert’s Brief History of PSA Posters here.

Download the free anti-xenophobia PSAs Poster House commissioned from designer Rachel Gingrich early in the pandemic here.

Related Content:

Download Beautiful Free Posters Celebrating the Achievements of Living Female STEM Leaders

Salvador Dalí Creates a Chilling Anti-Venereal Disease Poster During World War II

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...MoMA’s Online Courses Let You Study Modern & Contemporary Art and Earn a Certificate

The labels “modern art” and “contemporary art” don’t easily pull apart from one another. In a strictly historical sense, the former refers to art produced in the era we call modernity, beginning in the mid-19th century. And according to its etymology, the latter refers to art produced at the same time as something else: there is art “contemporary” with, say, the Italian Renaissance, but also art “contemporary” with our own lives. You’ll have a much clearer idea of this distinction — and of what people mean when they use the relevant terms today — if you take the Modern and Contemporary Art and Design Specialization, a set of courses from the Museum of Modern Art (aka MoMA) in New York.

Offered on the online education platform Coursera, the Modern and Contemporary Art and Design Specialization promises to “introduce you to the art of our time.” In its first course, Modern Art & Ideas, you’ll learn “how artists have taken inspiration from their environment and responded to social issues over the past 150 years.”

In the second, Seeing through Photographs (whose trailer appears above), you’ll explore photography “from its origins in the mid-1800s through the present.” The third, What Is Contemporary Art?, introduces works of the past four decades “ranging from 3‑D-printed glass and fiber sculptures to performances in a factory.” The final course, Fashion as Design, affords the opportunity to “learn from makers working with clothing every day — and, in some cases, reinventing it for the future.”

You can view the entire Contemporary Art and Design Specialization for free, by “auditing” its courses. Alternatively, you can join the paid track, which costs $39 USD per month, which at Coursera’s suggested pace of seven months to complete (including a “hands-on project” for each course) comes out to $273 overall. Then, when you finish the specialization, you’ll “earn a Certificate that you can share with prospective employers and your professional network.” Whether you go the audit or certificate route, you’ll earn an understanding of “modern art” and “contemporary art” as they’re created and regarded here in the 21st century: the era deep into modernity in which we live, and one in which the boundaries of art itself — not just the adjectives preceding it — show no sign of ceasing to expand.

Note: Open Culture has a partnership with Coursera. If readers enroll in certain Coursera courses and programs, it helps support Open Culture.

Related Content:

Take Seven Free Courses From the Museum of Modern Art (aka MoMA)

What Is Contemporary Art?: A Free Online Course from The Museum of Modern Art

How to Make a Savile Row Suit: A Short Documentary from the Museum of Modern Art

Art Historian Provides Hilarious & Surprisingly Efficient Art History Lessons on TikTok

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The Life & Music of the Godmother of Rock and Roll, Sister Rosetta Tharpe

When I was a wee lad I was interested in the history of rock and roll. Where did it come from? Who started it? But also when I was wee, there didn’t seem to be a lot of information around, certainly not in my library downtown. But when Muddy Waters died in 1983, I started to understand that rock and roll was sped-up blues, and pieces started to slot together. However, women weren’t part of the equation. (Blame Rolling Stone Magazine).

That’s a long way of saying the Sister Rosetta Tharpe should be better known than she is, especially as one dubbed the Godmother of Rock and Roll. Playing scratchy, distorted electric guitar and singing as if on a direct line to heaven, Tharpe would go on to influence everybody from Elvis Presley to Chuck Berry, and everybody who came after her. So why is she not more of a household name?

The 2011 BBC documentary above (split into four 15-minute chunks) resuscitates a legend who not only played a mean guitar but set the standard for the gospel-crossover artist, making a name on the gospel circuit, but making her fame in the secular nightclubs of America. Tharpe’s distinction is that she returned to gospel without losing any of her edge.

A precocious youngster in Arkansas during the early 1920s, she became the star of her Pentecostal church starting at four years old. Raised by her mother, then forced into an arranged marriage at 19-years-old to an older preacher, Thomas Tharpe, she kept his name when she left their abusive marriage. She and her mother relocated to Chicago, where blues and jazz were intermingling in a hothouse culture. Decca signed her, and although she told her churchgoing friends that she had to sing these secular songs because of that darned seven-year contract, Tharpe rose to fame quickly. The footage of her singing in front of the Cotton Club band led by Lucky Millinder is one of a cheeky, charming 23 year old.

As the doc makes clear, Tharpe had a rebellious streak, didn’t do what she was told, and pushed boundaries in a very segregated America. She invited the all-white Jordanaires to tour with her, surprising house managers and booking agents alike. And she carried on a love affair and creative partnership with fellow gospel singer Marie Knight for decades, very much on the down low.

So perhaps this is the reason Tharpe has not been on our collective radar—we’ve been slow to admit that rock guitar was created by a queer black woman devoted to the Lord. Nobody in the audience knew this, though, at the abandoned railway station at Wilbraham Road, Manchester, in May 1964. On one side of the station’s tracks, British teenagers were gathered to hear raw, rock and roll from America. On the other side, Tharpe stands with her guitar, wearing a thick coat to protect her from the spring rain. Backed by her band, she channels a holy force and sings about the rain of the Great Flood, the lyrics abstract and repetitive, as if in a trance. The footage opens the documentary and makes as good a case as any of why Tharpe should be part of the pantheon of rock royalty. (You can see the whole clip here.) Back in the States, Tharpe had been eclipsed by Mahalia Jackson, but the Brits didn’t know any of that. They just sense they’ve tapped into one of the sources for the music exploding around them.

It took until 2018 for Tharpe to be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, years after all those white boy copycats. Now is the time to re-discover her and hear what you’ve been missing.

Related Content:

New Web Project Immortalizes the Overlooked Women Who Helped Create Rock and Roll in the 1950s

An Introduction to Sister Rosetta Tharpe

Muddy Waters and Friends on the Blues and Gospel Train, 1964

Watch the Hot Guitar Solos of Sister Rosetta Tharpe

Revisit The Life & Music of Sister Rosetta Tharpe: ‘The Godmother of Rock and Roll’

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

Read More...How the COVID-19 Vaccines Could Be Created So Quickly: Two Animated Videos Explain the How mRNA Vaccines Were Developed, and How They Work

The world now has COVID-19 vaccines, of which more and more people are receiving their doses every day. A year and a half ago the world did not have COVID-19 vaccines, though it was fast becoming clear how soon it would need them. The subsequent development of the ones now being deployed around the world took not just less than a year and a half but less than a year, an impressive speed even to many of us who never dug deep into medical science. The achievement owes in part to the use of mRNA, a term most of us may recall only dimly from biology classes; through the pandemic, messenger ribonucleic acid, to use its full name, has proven if not the savior of humanity, then at least the very molecule we needed.

One shouldn’t get “the idea that these vaccines came out of nowhere.” On Twitter, Dan Rather — these days a more outspoken figure than ever — calls the prevalence such a notion “a failure of science communication with tragic results,” describing the vaccines as “the result of DECADES of basic research in MULTIPLE fields building on the BREADTH and DEPTH of human knowledge.”

You can get a clearer sense of what that research has involved through videos like the animated TED-Ed explainer above. “In the twentieth century, most vaccines took well over a decade to research, test, and produce,” says its narrator. “But the vaccines for COVID-19 cleared the threshold for use in less than eleven months.” The “secret”? mRNA.

A “naturally occurring molecule that encodes the instructions for occurring proteins,” mRNA can be used in vaccines to “safely introduce our body to a virus.” Researchers first “encode trillions of mRNA molecules with instructions for a specific viral protein.” Then they inject those molecules into a specially designed “nanoparticle” also containing lipids, sugars, and salts. When it reaches our cells, this nanoparticle triggers our immune response: the body produces “antibodies to fight that viral protein, that will then stick around to defend against future COVID-19 infections.” And all of this happens without the vaccine altering out DNA,

While mRNA vaccines will “have a big impact on how we fight COVID-19,” says the narrator of the Vox video above, “their real impact is just beginning.” Their development marked “a turning point for the pandemic,” but given their potential applications in the battles against a host of other, even deadlier diseases (e.g., HIV), “the pandemic might also be a turning point for vaccines.”

Related Content:

How Fast Can a Vaccine Be Made?: An Animated Introduction

How Do Vaccines (Including the COVID-19 Vaccines) Work?: Watch Animated Introductions

How Vaccines Improved Our World In One Graphic

19th Century Maps Visualize Measles in America Before the Miracle of Vaccines

Yo-Yo Ma Plays an Impromptu Performance in Vaccine Clinic After Receiving 2nd Dose

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The Wicked Scene in Amadeus When Mozart Mocked the Talents of His Rival Antonio Salieri: How Much Does the Film Square with Reality?

Pity the ghost of Antonio Salieri, “one of history’s all-time losers — a bystander run over by a Mack truck of malicious gossip,” writes Alex Ross at The New Yorker. The rumors began even before his death. “In 1825, a story that he had poisoned Mozart went around Vienna. In 1830, Alexander Pushkin used that rumor as the basis for his play ‘Mozart and Salieri,’ casting the former as the doltish genius and the latter as a jealous schemer.” The stories became further embellished in an opera by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, then again in 1979 by British playwright Peter Shaffer, whose Amadeus, “a sophisticated variation on Pushkin’s concept, …became a mainstay of the modern stage.”

In 1984, these fictions became the basis of Miloš Forman’s Amadeus, written by Shaffer for the screen. The film further solidifies Salieri’s villainy in F. Murray Abraham’s Oscar-winning performance of his envy and despair. Like all great cinematic villains, Salieri is shown to have good reason for his hatred of the hero, played as a manic toddler by Thomas Hulce, who was nominated for the same best-actor award Abraham won. In their first meeting (above), Mozart humiliates Salieri in the presence of the Emperor, insulting him several times and showing that Salieri’s years of toil and devotion are worth little more than what the German prodigy mastered as a small child, and could improve upon immeasurably with hardly any effort at all.

Is there truth to this scene? In general, the history of Amadeus is “laughably wrong,” Alex von Tunzelmann writes at The Guardian, though maybe the joke’s on us if we believe it. As Forman’s film takes pains to show, what we see on screen is not an objective point of view, but that of an aged, embittered, insane man remembering his past with regret. Salieri is a most unreliable narrator, and Forman an unreliable storyteller. The supposed “Welcome March” composed for Mozart in the scene above is not a Salieri composition at all, but a simplification of the aria from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, which Hulce-as-Mozart then transforms into the actual tune of the aria.

Other inaccuracies abound. The Salieri of history was not “a sexually frustrated, dried-up old bachelor,” von Tunzelmann notes. “He had eight children by his wife, and is reputed have had at least one mistress.” He was also more colleague and friendly competitor than enemy of the newly-arrived Mozart in Vienna. The two even composed a piece together for singer Nancy Storace, who played the first Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro. While Mozart wrote to his father of a shadowy cabal arrayed against him at court, there is no evidence of a plot, and Mozart could be, by all accounts, just as puerile and obnoxious as his portrayal in the film.

Mozart did die a pauper from a mysterious illness at 34. (He did not dictate the final passages of his Requiem to Salieri). And Salieri did later confess to poisoning Mozart while he was aged and in a temporary state of mental illness, then retracted the claim when he later recovered. (“Let’s be honest,” writes von Tunzelmann, “nobody seriously thinks Salieri murdered Mozart.”) These are the barest historical facts upon which Amadeus’s infamous rivalry rests. The Salieri of the film is a fictional construction, created, as actor Simon Callow said of Shaffer’s play, to serve “a vast meditation on the relationship between genius and talent.”

In Forman’s film, the theme becomes the relationship between genius and mediocrity. But to call Salieri a mediocrity — or the “patron saint of mediocrities,” as Shaffer does in his play — “sets the bar for mediocrity too high,” Ross argues. “His music is worth hearing. Mozart was a greater composer, but not immeasurably greater.” Furthermore, “amid the procession of megalomaniacs, misanthropes, and basket cases who make up the classical pantheon, [Salieri] seems to have been one of the more likable fellows.”

Learn more about Salieri’s life and work in Ross’s New Yorker profile, and hear “4 Operas by Antonio Salieri You Should Listen To” at Opera Wire.

Related Content:

Mozart’s Diary Where He Composed His Final Masterpieces Is Now Digitized and Available Online

The Letters of Mozart’s Sister Maria Anna Get Transformed into Music

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

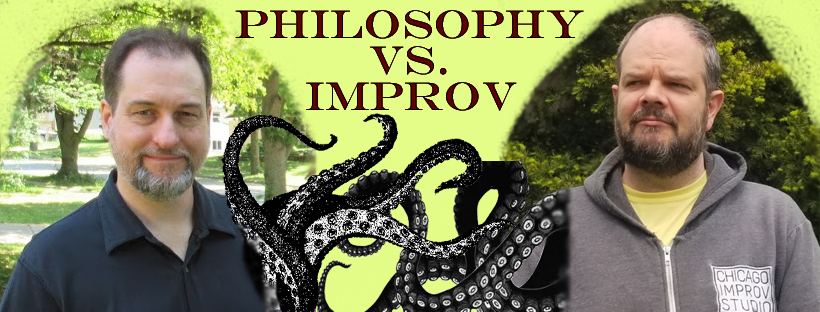

Read More...Philosophy vs. Improv: A New Podcast from The Partially Examined Life and Chicago Improv Studio

The Partially Examined Life Philosophy Podcast has been sharing reading-group discussions on classic philosophy texts for well over a decade, with over 40 million downloads to date.

However, interactive conversations about texts you probably haven’t read can be difficult to follow no matter how much we try to make them accessible, and a decade of history means that many names that might be dropped that those newly checking in may or may not be familiar with.

I’m one of the hosts of that podcast, and while I’m very happy with the format and thrilled to have reached so many people with it, I also appreciate the dynamic of a one-on-one tutoring interchange, and I stand firmly behind one of the original rules of The Partially Examined Life: No name-dropping.

As we read more complicated texts, our interest becomes figuring out what the philosopher meant, and only secondarily whether that meaning actually relates to something in people’s actual lives. Yes, we are critical (some say too critical) of the subject-matter, but we’re also big fans; we could bask in the literary glow of Hegel or Plato or Simone de Beauvoir or Hannah Arendt all day, and have often done so.

My newest podcast, Philosophy vs. Improv, is reciprocal tutoring realized as comedy (or at least performance art?). As someone who studied philosophy for many years in school and has then been hosting The Partially Examined Life for so long, I’m in a good position to come up with particular philosophical points worth teaching to a new learner.

My Philosophy vs. Improv co-host is Bill Arnett, founder of the Chicago Improv Studio, author of The Complete Improviser, and the former training director at Chicago’s famed iO Theater. He has appeared repeatedly on the Hello From the Magic Tavern improv comedy podcast as a character named Metamore who leads the show’s hosts (who are all fantasy characters a la Tolkein or Narnia) in a table-top role-playing game called Offices and Bosses. This and other shows ignited in me an urge to learn the fundamentals of improv comedy, and so each Philosophy vs. Improv episode, Bill comes up with some trick of the trade to try to teach me.

There are two rules of engagement: First, we can’t just state up front what the lesson is. We can ask each other questions, go through exercises, and otherwise discuss the material, but the lesson should emerge naturally. Second, we don’t take turns in trying to teach each other. As he’s making me act out scenes, I’m trying to set up those scenes or have my character react in such a way to exemplify my philosophical point. As we’re discussing philosophy, Bill is relating it to comparable points about improv. Of course, we’re both interested in learning as well as teaching, so the “vs.” in the show’s title is not so much competition between us as between which lesson ends up more nearly producing its intended effect in the other person.

It is surprising how smoothly these dueling lessons often fit together, as lessens about ethics in particular, about the art of living, are very much relevant to the improvisational skills of being present, presenting yourself, discovering the reality of a situation, and exploring truths of character. Fiction is often a very effective vehicle for addressing philosophy, whether the characters themselves are talking philosophically (even if they’re animals, cave men, or otherwise in a non-typical situation for discussion), or perhaps we’re embodying some political situation or thought experiment that we’re subjecting to philosophical analysis.

Likewise, back to the days of Plato, a dose of irony in discussing philosophy can be useful, and this format allows us to not just be ourselves on a podcast discussing philosophy, but at any point to launch into some comedy bit, and in this way show the absurdity of views we’re arguing against or just play with the ideas in a manner that I think enhances mental flexibility, which is essential both for improvisation and for philosophical creativity.

Listen to the latest episode (#7), entitled “Meritocracy Now!”

Start listening with Philosophy vs. Improv episode 1.

For more information, see philosophyimprov.com.

Mark Linsenmayer is the host of four podcasts: Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast, Nakedly Examined Music, The Partially Examined Life, and Philosophy vs. Improv.

Read More...