How Did the Egyptians Make Mummies? An Animated Introduction to the Ancient Art of Mummification

Not every child looks forward to a trip to the museum, but how many have failed to thrill at the sight of an ancient Egyptian mummy? How many adults, for that matter, can resist the fascination of this well over 5000-year-old process of preserving dead bodies in a state if not perfectly lifelike then at least eerily intact? If you’ve ever wondered exactly how mummification worked — or if you’ve simply forgotten the descriptions accompanying the displays you saw on those museum trips — this short video from the Getty Museum’s Youtube channel provides an insight into how the ancient Egyptians did it.

The video uses a real mummy as a case study, the preserved body of a twenty-year-old man named Herakleides (as we know because his mummifiers, though themselves unidentified, wrote it on his feet), who died in the first century A.D. He had most of his internal organs removed — even his heart, which common practice usually dictated leaving in, but for some reason not his lungs — and spent forty days buried in salt that drew every last bit of moisture out of him.

He then received rubbings of perfumed oils, followed by a poured-on layer of resin to which strips of linen (the mummy’s characteristically copious “bandages” of popular culture) could adhere. Wrapped onto a board, equipped with a “mysterious pouch” as well as a mummified ibis, and covered with an unusual red shroud emblazoned with symbols and a portrait of himself, Herakleides was ready for his journey into the afterlife.

“Such elaborate burial practices might suggest that the Egyptians were preoccupied with thoughts of death,” says the Smithsonian’s page on Egyptian mummies. “On the contrary, they began early to make plans for their death because of their great love of life. They could think of no life better than the present, and they wanted to be sure it would continue after death.” The ancient Egyptians believed “that the mummified body was the home for this soul or spirit. If the body was destroyed, the spirit might be lost.”

If you find yourself sharing these beliefs, do have a look at National Geographic’s guide on how to make a mummy in 70 days or less. And just as you’d need to arrange the right ingredients to prepare a satisfying meal, something else the Egyptians enjoyed, don’t attempt any mummification at home without making sure you’re fully stocked with resin, ointments, lichen, strawdust, beeswax, palm wine, incense, and myrrh. And it goes without saying that however many feet of wrappings you’ve got, it couldn’t hurt to have more.

Related Content:

The Opening of King Tut’s Tomb, Shown in Stunning Colorized Photos (1923–5)

How the Egyptian Pyramids Were Built: A New Theory in 3D Animation

Try the Oldest Known Recipe For Toothpaste: From Ancient Egypt, Circa the 4th Century BC

The Turin Erotic Papyrus: The Oldest Known Depiction of Human Sexuality (Circa 1150 B.C.E.)

A Drone’s Eye View of the Ancient Pyramids of Egypt, Sudan & Mexico

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Judy Blume Now Teaching an Online Course on Writing

FYI: If you sign up for a MasterClass course by clicking on the affiliate links in this post, Open Culture will receive a small fee that helps support our operation.

After announcing that Martin Scorsese will be teaching an online course on filmmaking, MasterClass made it known today that Judy Blume has created an online course on Writing. In 24 lessons, the beloved author of Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret and Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing will show you “how to develop vibrant characters and hook your readers.” The individual course costs $90 and is now ready go. You can also buy an All-Access Annual Pass for $180 and explore every course in the MasterClass catalogue. Some courses worth exploring include:

- Herbie Hancock on Jazz

- Garry Kasparov on Chess

- Dr. Jane Goodall on the Environment

- David Mamet on Dramatic Writing

- Steve Martin on Comedy

- Aaron Sorkin on Screenwriting

- Gordon Ramsay on Cooking

You can take this class by signing up for a MasterClass’ All Access Pass. The All Access Pass will give you instant access to this course and 85 others for a 12-month period.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Enter an Archive of 6,000 Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized and Free to Read Online

Hayao Miyazaki Picks His 50 Favorite Children’s Books

Read More...When John Cage & Marcel Duchamp Played Chess on a Chessboard That Turned Chess Moves Into Electronic Music (1968)

Photograph by Lynn Rosenthal

When is a chess game not a chess game?

When it’s played between Marcel Duchamp and John Cage.

Both the man who turned a urinal into a piece of modern art and the man who reduced musical composition all the way down to silence were fans of taking things to absurd conclusions. And they were both fans of chess; Duchamp the grand master and Cage the dutiful student. Asked in 1974 whether Duchamp was a good teacher, Cage replied, “I was using chess as a pretext to be with him. I didn’t learn, unfortunately, while he was alive to play well.”

But Cage seemed to have little interest in competition. “Duchamp once watched me playing and became indignant when I didn’t win,” he said. “He accused me of not wanting to win.” Instead, he approached chess as he approached the piano—as a decoy, a feint, that leads into another kind of game entirely. In a 1944 tribute to Duchamp, he painted a chessboard that was actually a musical score, and, in 1968, he arranged a public game as a pretext for a musical performance called Reunion, performed in Toronto with Duchamp and his wife Teeny (we have no film of the game-slash-concert; you can see Cage play Teeny in the video above).

Cage was an admirer of the elder artist for over 20 years, playing chess with him frequently. But he “didn’t want to bother Duchamp with his friendship,” writes Sylvere Lotringer, “until he realized that Duchamp’s health was failing. Then he decided to actively seek his company.” Playing on an electronic chess board designed by Lowell Cross, known as the inventor of the laser light show, the two created an extemporaneous composition that lasted as long as the audience, and Duchamp, could tolerate. “The concert,” Cross remembered on the fortieth anniversary of the piece, “began shortly after 8:30 on the evening of March 5, 1968, and concluded at approximately 1:00 a.m. the next morning.”

Debunking a number of misconceptions about the chessboard, Cross explains that its operation “depended upon the covering or uncovering of its 64 photoresistors.” It also contained contact microphones so that “the audience could hear the physical moves of the pieces of the board.” When either player made a move, it triggered one of several electronic “sound-generating systems” created by composers David Behrman, Gordan Mumma, David Tudor, and Cross himself. Additionally, “oscilloscopic images emanated from… modified monochrome and color television screens, which provided visual monitoring of some of the sound events passing through the chessboard.”

As Lotringer describes the scene, the two modernist giants “played until the room emptied. Without a word said, Cage had managed to turn the chess game (Duchamp’s ostensive refusal to work) into a working performance…. Playing chess that night extended life into art—or vice versa. All it took was plugging in their brains to a set of instruments, converting nerve signals into sounds. Eyes became ears, moves music.” Duchamp had given the impression he was done making art. “Cage found a way to lure him into one final public appearance as an artist,” notes the Toronto Dreams Project blog.

Indeed, Cage may have been formulating the idea for over twenty years, each time he sat down to play a game with Duchamp, and lost. When Duchamp arrived in Canada for the performance at what was called the Sightsoundsystems Festival, he had no idea that he would be participating in the headlining event.

What he found when he arrived was a surreal scene. Two of the greatest artists of the twentieth century took their seats in the middle of the stage at the Ryerson Theatre, bathed in bright light and the gaze of the audience. Photographers circled around them, shutters snapping; a movie camera whirred. The stage was a mess of gadgets. There were wires everywhere; a tangle of them plugged right into side of the chessboard. A pair of TV screens was set up on either side of the stage. The Toronto Star called it “a cross between an electronic factory and a movie set.”

Cage lost, as usual, though he was more evenly matched when he played Duchamp’s wife. The three of them, wrote the Globe, were “like figures in a Beckett play, locked in some meaningless game. The audience, staring silently and sullenly at what was placed before it, was itself a character; and its role was as meaningless as the others. It was total non-communication, all around.” The wires running from the chessboard connected to “tuners, amplifiers and all manner of electronic gadgetry,” the Star wrote, filling the room with “screeches, buzzes, twitters and rasps.”

The Star pronounced the event “infinitely boring,” a widely shared critical assessment of the night. (Cage explains the Zen of boredom in his voice-over at the top.) But we can hardly expect most reviewers of either artist’s most experimental work to respond with less than bewilderment, if not outright hostility. It was to be Duchamp’s last public appearance. He passed away a few months later. For Cage, the evening had been a success. As Cross put it, Reunion was “a public celebration of Cage’s delight in living everyday life as an art form.”

Everyday life with Duchamp meant playing chess, and there were few greater influences than Duchamp on Cage’s conceptual approach to what music could be—and what could be music. “Like Duchamp,” writes PBS, “Cage found music around him and did not necessarily rely on expressing something from within.” Further up, see Cage’s 1944, Duchamp-inspired “Chess Pieces” performed on harp and accordion, and above hear a piece he wrote for Duchamp for a sequence in Hans Richter’s 1947 surrealist film Dreams that Money Can Buy.

To delve deeper, you can explore the book, Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess by Francis M. Naumann.

Related Content:

Play Chess Against the Ghost of Marcel Duchamp: A Free Online Chess Game

The Music of Avant-Garde Composer John Cage Now Available in a Free Online Archive

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Watch the New Anime Prequel to Blade Runner 2049, by Famed Japanese Animator Shinichiro Watanabe

The run-up to Blade Runner 2049, befitting what now looks like the cinematic event of the decade, has consisted of not just marketing hype (though it does include plenty of that) but genuine artistic material as well. Last month we featured Nexus: 2036, the first of three short “prequels” to Denis Villeneuve’s upcoming Blade Runner sequel. That one and its follow up 2048: Nowhere to Run, both directed by Luke Scott (son of Blade Runner director Ridley Scott), use live action to fill in some of the story between the 2019 of the first movie and the 2049 of the second. The just-released third short, Black Out 2022, from Cowboy Bebop director Shinichirō Watanabe, brings the Blade Runner universe into the realm of Japanese animation.

“Blade Runner was definitely the movie that influenced me the most as an anime director,” says Watanabe in the preview of his prequel down below. He and other Japanese viewers understood the film’s power long before most anyone in the West (with the notable exception of Philip K. Dick, author of its source material), and Japanese artists began paying tribute to it almost immediately.

In a sense, Blade Runner took anime form thirty years ago: Katsuhito Akiyama’s animated series Bubblegum Crisis, the story of artificial humans (called “booomers” instead of replicants) run amok and the advanced police team (called “Knight Sabers” instead of “Blade Runners”) who hunt them down in a Tokyo of the future rebuilt after a disastrous earthquake, could hardly wear its influence more openly.

Filled with visual, sonic, and thematic references to the original Blade Runner while taking the story in new directions — and also introducing two new replicant characters — Watanabe’s Black Out 2022–viewable up top–depicts the events leading up to the detonation of an electromagnetic pulse that destroys the electronics and machinery on which humanity has become so reliant. Humanity blames the replicants, and so begins a period of prohibition on replicant production, only brought to an end by the efforts of Niander Wallace, the character so eerily played by Jared Leto in Nexus: 2036. Blade Runner 2049 will pick things up 26 years after the EMP attack. What shape will Los Angeles be in then? What shape will the cat-and-mouse game between replicants and Blade Runners take there? We’ll find out, and surely in no small amount of detail, next month.

Related Content:

Jared Leto Stars in a New Prequel to Blade Runner 2049: Watch It Free Online

The Official Trailer for Ridley Scott’s Long-Awaited Blade Runner Sequel Is Finally Out

Watch an Animated Version of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner Made of 12,597 Watercolor Paintings

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Watch the New Trailer for Wes Anderson’s Stop Motion Film, Isle of Dogs, Inspired by Akira Kurosawa

It surprised everyone, even die-hard fans, when Wes Anderson announced that he would not just adapt Roald Dahl’s children’s book Fantastic Mr. Fox for the screen, but do it with stop-motion animation. But after we’d all given it a bit of thought, it made sense: Anderson’s films and Dahl’s stories do share a certain sense of inventive humor, and stepping away from live action would finally allow the director of such detail-oriented pictures as Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou fuller control over the visuals. Eight years later, we find Anderson overseeing another team of animators to tell another, even more fantastical-looking story, this one set not in an England of the past but a Japan of the future.

There, according to the project’s newly released trailer, “canine saturation has reached epic proportions. An outbreak of dog flu rips through the city of Megasaki. Mayor Kobayashi issues emergency orders calling for a hasty quarantine. Trash Island becomes an exile colony: the Isle of Dogs.” Equals in furriness, if not attire, to Fantastic Mr. Fox’s woodland friends and voiced by the likes of Jeff Goldblum, Scarlet Johansson, Tilda Swinton, and of course Bill Murray (in a cast also including Japanese performers like Ken Watanabe, Mari Natsuki, and Yoko Ono — yes, that Yoko Ono), the canines of various colors and sizes forcibly relocated to the bleak titular setting must band together into a kind of ragtag family.

Anderson must find himself very much at home in this thematic territory by now. It would also have suited the towering figure in Japanese film to whom Isle of Dogs pays tribute. Although Anderson has cited the 1960s and 70s stop-animation holiday specials of Rankin/Bass like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and The Little Drummer Boy — all produced, incidentally, in Japan — as one inspiration, he also said on an ArteTV Q&A earlier this year that “the new film is really less influenced by stop-motion movies than it is by Akira Kurosawa.” Perhaps he envisioned Atari Kobayashi, the boy who journeys to Trash Island to retrieve his lost companion, as a twelve-year-old version of one of Kurosawa’s lone heroes.

And perhaps it owes to Kurosawa that the setting — at least from what the trailer reveals — combines elements of an imagined future with the look and feel of Japan’s rapidly developing mid-20th century, a period that has long fascinated Anderson in its European incarnations but one captured crisply in Kurosawa’s homeland in crime movies like High and Low and The Bad Sleep Well. Anderson has made little to no reference to the Land of the Rising Sun before, but his interest makes sense: no land better understands what Anderson has expressed more vividly with every project, the richness of the aesthetic mixture of the past and future that always surrounds us. And from what I could tell on my last visit there, its dog situation remains blessedly under control — for now.

via Uncrate

Related Content:

A Complete Collection of Wes Anderson Video Essays

The Geometric Beauty of Akira Kurosawa and Wes Anderson’s Films

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Circus Artist Roxana Küwen Will Captivate You with Her Foot Juggling Routine

Roxana Küwen is a German-born circus artist who “likes to take her audience into her world and make them be astonished, confused or amazed by playing with categories and presence.” Witness the video above, where Küwen does something quite simple. She puts her feet next to her hands and moves her 20 digits in unison. Familiar body parts are put into strange motion, leaving you feeling charmed. But also a bit disconcerted.

Then Roxana starts her foot juggling routine. It’s not the most high velocity, risk-filled juggling act. The balls move slowly and never get more than a few feet off of the ground. There’s a strange simplicity to it, though captivating nonetheless.

Related Content

How Marcel Marceau Started Miming to Save Children from the Holocaust

Read More...How a Recording Studio Mishap Created the Famous Drum Sound That Defined 80s Music & Beyond

It’s not a subtle effect, by any means, which is precisely what makes it so effective. Gated reverb, the sound of an airbag deploying or weather balloon suddenly blowing out, an airy thud that pervades eighties pop, and the work of every musician thereafter who has referenced eighties pop, including CHVRCHES, Tegan and Sara, M83, Beyoncé, and Lorde, to name but a very few.

Before them came the pummeling gated drums of Kate Bush, Bruce Springsteen, Prince, Depeche Mode, New Order, Cocteau Twins, David Bowie, and Grace Jones, who turned Roxy Music’s “Love is the Drug” into a strict machine with the gated reverb of her 1980 cover.

Roxy Music caught up quickly with songs like the lovely “More Than This” on 1982’s Avalon, but Jones was an early adopter of the effect, which—like many a legendary piece of studio wizardry—came about entirely by accident, during a 1979 recording session for Peter Gabriel’s eerie solo track “Intruder.”

On the drums—Vox’s Estelle Caswell tells us in the explainer video at the top—was Gabriel’s former Genesis bandmate Phil Collins, and in the control room, recording engineer Hugh Padgham, who had inadvertently left a talkback mic on in the studio.

The mic happened to be running through a heavy compressor, which squashed the sound, and a noise gate that clamped down on the reverberating drums, cutting off the natural decay and creating a short, sharp echo that cut right through any mix. After hearing the sound, Gabriel arranged “Intruder” around it, and the following year, Collins and Padgham created the most iconic use of gated reverb in pop music history on “In the Air Tonight.” “Thanks to a happy accident,” says Caswell, “the sound of the 80s was born.” Also the sound of the oughties and beyond, as you’ll hear in the 38-s0ng playlist above, featuring many of the pioneers of gated reverb and the many earnest revivalists who made it hip, and ubiquitous, again.

Related Content:

All Hail the Beat: How the 1980 Roland TR-808 Drum Machine Changed Pop Music

The “Amen Break”: The Most Famous 6‑Second Drum Loop & How It Spawned a Sampling Revolution

Two Guitar Effects That Revolutionized Rock: The Invention of the Wah-Wah & Fuzz Pedals

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Watch Author Chuck Palahniuk Read Fight Club 4 Kids

The first rule of Horsing Around Club is: You do not talk about Horsing Around Club. ― Chuck Palahniuk, Fight Club for Kids

Retooling a popular show, film, or comic to feature younger versions of the characters, their personalities and relationships virtually unchanged, can be a serious, if cynical source of income for the original creators.

The Muppets, Archie, Sherlock Holmes, and James Bond have all given birth to spin-off babies.

So why not author Chuck Palahniuk?

Perhaps because spin-off babies are designed to gently ensnare a new and younger audience, and Palahniuk, whose 2002 novel Lullaby hinged on a nursery rhyme that kills children in their cribs, is unlikely to file down the dark, twisted edges that have won him a cult following.

That said, his most recent title is formatted as a coloring book, with another due to drop later this fall.

The same spirit of mischief drives Fight Club for Kids, which mercifully will not be hitting the children’s section of your local bookstore in time for the upcoming holiday season (or ever).

Much like Tyler Durden, Palahniuk’s most infamous creation, this title is but a figment, existing only in the above video, where it is read by its putative author.

If you think Samuel L. Jackson’s narration of Go the F**k to Sleep—which can actually be purchased in book form—represents the height of adult readers running off the rails, you ain’t heard nothing yet:

The horseplay would go on until it was done

And everyone who did it would always have fun

Especially the Boy Who Had No Name

Who once just, like, beat this dude, who was actually Jared Leto in the movie, which was so fuckin’ cool and intense, and he’s just pummeling this guy and of course, being Jared Leto, he was essentially a model, but when our guy is done with him, he’s just this purple, bloated, chewed up bubblegum-looking motherfucker covered in blood, head to toe!

(The second rule of Horsing Around Club is: You DO NOT TALK ABOUT HORSING AROUND CLUB!)

Find more printable Chuck Palahniuk coloring pages here.

via Mashable

Related Content:

David Foster Wallace’s Famous Commencement Speech “This is Water” Visualized in a Short Film

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

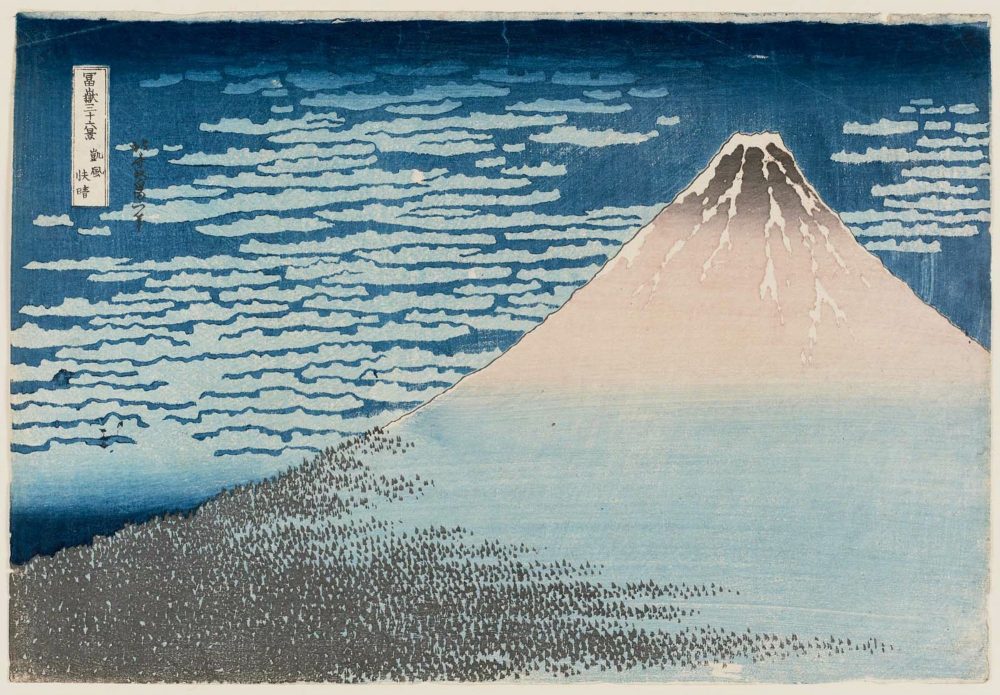

Most of us have now and again seen and appreciated Japanese woodblock prints, especially those in the tradition of ukiyo‑e, those “captivating images of seductive courtesans, exciting kabuki actors, and famous romantic vistas.” Those words come from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, whose essay on the art form describes how, “in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, woodblock prints depicting courtesans and actors were much sought after by tourists to Edo and came to be known as ‘Edo pictures.’ In 1765, new technology made possible the production of single-sheet prints in a range of colors,” which brought about “the golden age of printmaking.”

At that time, “the popularity of women and actors as subjects began to decline. During the early nineteenth century, Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) brought the art of ukiyo‑e full circle, back to landscape views, often with a seasonal theme, that are among the masterpieces of world printmaking.”

Even if you’ve only seen a few Japanese woodblock prints, you’ve seen the work of Hiroshige and Hokusai, thousands of examples of which you can find in the vast Japanese woodblock database of Ukiyo‑e.org.

This English-Japanese bilingual site, a project of programmer and Khan Academy engineer John Resig, launched in 2012 and now boasts 213,000 prints from 24 museums, universities, libraries, auction houses, and dealers worldwide. You can search it by text or image (if you happen to have one of a print you’d like to identify), or you can browse by period and artist: not just the “golden age” of Hiroshige and Hokusai (1804 to 1868), but ukiyo-e’s early years (early-mid 1700s), the birth of full-color printing (1740s to 1780s), the popularization of woodblock printing (1804 to 1868), the Meiji period (1868 to 1912), the artist-centric Shin Hanga and Sosaku Hanga movements (1915 to 1940s), and even the modern and contemporary era (1950s to now).

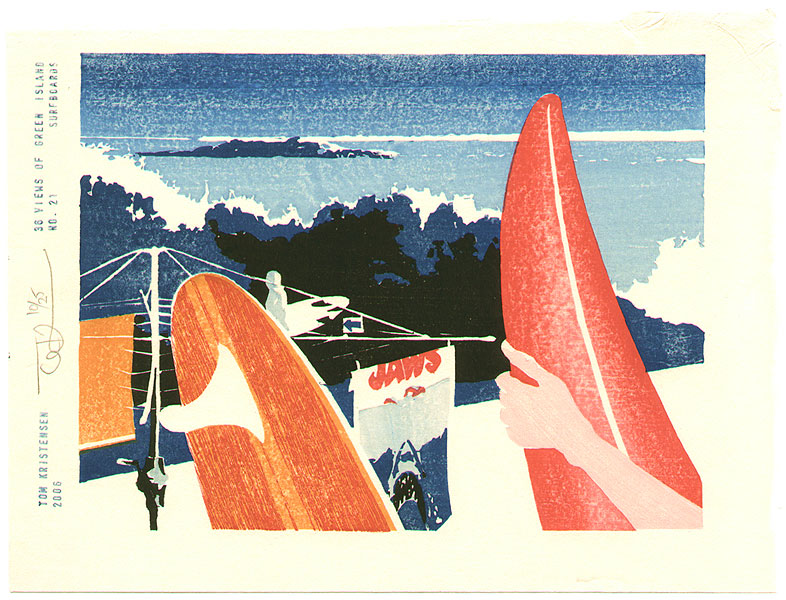

That last group includes woodblock prints of styles and subject matter one certainly wouldn’t expect from classic ukiyo‑e, though the works never go completely without connection to the tradition of previous masters. Some of these more recent practitioners, like Danish-German-Australian printmaker Tom Kristensen, have even gone so far as to not be Japanese. Kristensen, who “works in typically Japanese ‘sosaku hanga’ style: self-carved and self-printed with natural Japanese pigments on hand-made washi paper,” has produced works like the 36 Views of Green Island series, of which number 21 appears below. The surfboards may at first seem incongruous, but one imagines that Hiroshige and Hokusai, those two great appreciators of waves, might approve. Enter the digital archive here, and note that if you click on an image, and then click on it again, you can view it in a larger format.

Related Content:

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Harry Dean Stanton (RIP) Reads Poems by Charles Bukowski

Variety is reporting tonight that Harry Dean Stanton has died in Los Angeles, at the age of 91. He’s best remembered, of course, for his roles in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, HBO’s Big Love, Alex Cox’s Repo Man, and Wim Wender’s Paris, Texas. Over a 60 year career, Stanton made appearances in 116 films, 77 TV shows, and several music videos. He also lent his voice to an Alien video game and recorded poems by Charles Bukowski. Above and below, hear him read “Bluebird” and “Torched Out.” Both recordings come from the 2003 documentary, Bukowski: Born Into This. Back in 2012, Stanton headlined an L.A. tribute to the Los Angeles poet.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free

Tom Waits Reads Two Charles Bukowski Poems, “The Laughing Heart” and “Nirvana”

Read More...