Watch the Illustrated Version of “Alice’s Restaurant,” Arlo Guthrie’s Thanksgiving Counterculture Classic

Alice’s Restaurant. It’s now a Thanksgiving classic, and something of a tradition around here. Recorded in 1967, the 18+ minute counterculture song recounts Arlo Guthrie’s real encounter with the law, starting on Thanksgiving Day 1965. As the long song unfolds, we hear all about how a hippie-bating police officer, by the name of William “Obie” Obanhein, arrested Arlo for littering. (Cultural footnote: Obie previously posed for several Norman Rockwell paintings, including the well-known painting, “The Runaway,” that graced a 1958 cover of The Saturday Evening Post.) In fairly short order, Arlo pleads guilty to a misdemeanor charge, pays a $25 fine, and cleans up the thrash. But the story isn’t over. Not by a long shot. Later, when Arlo (son of Woody Guthrie) gets called up for the draft, the petty crime ironically becomes a basis for disqualifying him from military service in the Vietnam War. Guthrie recounts this with some bitterness as the song builds into a satirical protest against the war: “I’m sittin’ here on the Group W bench ’cause you want to know if I’m moral enough to join the Army, burn women, kids, houses and villages after bein’ a litterbug.” And then we’re back to the cheery chorus again: “You can get anything you want, at Alice’s Restaurant.”

We have featured Guthrie’s classic during past years. But, for this Thanksgiving, we give you the illustrated version. Happy Thanksgiving to everyone who plans to celebrate the holiday today.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Bob Dylan’s Thanksgiving Radio Show: A Playlist of 18 Delectable Songs

William S. Burroughs Reads His Sarcastic “Thanksgiving Prayer” in a 1988 Film By Gus Van Sant

Marilyn Monroe’s Handwritten Turkey-and-Stuffing Recipe

William Shatner Raps About How to Not Kill Yourself Deep Frying a Turkey

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 13 Tips for What to Do with Your Leftover Thanksgiving Turkey

Read More...The 1991 Tokyo Museum Exhibition That Was Only Accessible by Telephone, Fax & Modem: Features Works by Laurie Anderson, John Cage, William S. Burroughs, J.G. Ballard & Merce Cunningham

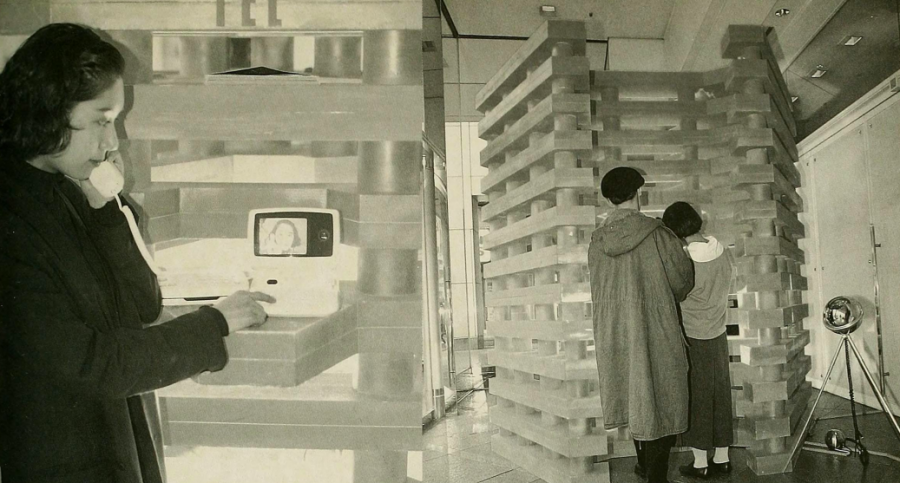

The deeper we get into the 21st century, the more energy and resources museums put into digitizing their offerings and making them available, free and worldwide, as virtual experiences on the internet. But what form would a virtual museum have taken before the internet as we know it today? Japanese telecommunications giant NTT (best known today in the form of the cellphone service provider NTT DoCoMo) developed one answer to that question in 1991: The Museum Inside the Telephone Network, an elaborate art exhibit accessible nowhere in the physical world but everywhere in Japan by telephone, fax, and even — in a highly limited, pre-World-Wide-Web fashion — computer modem.

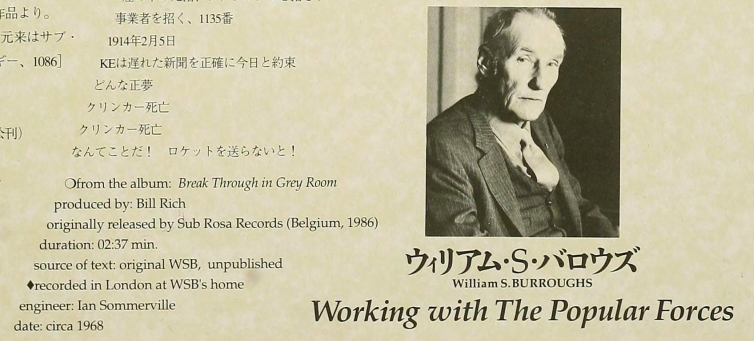

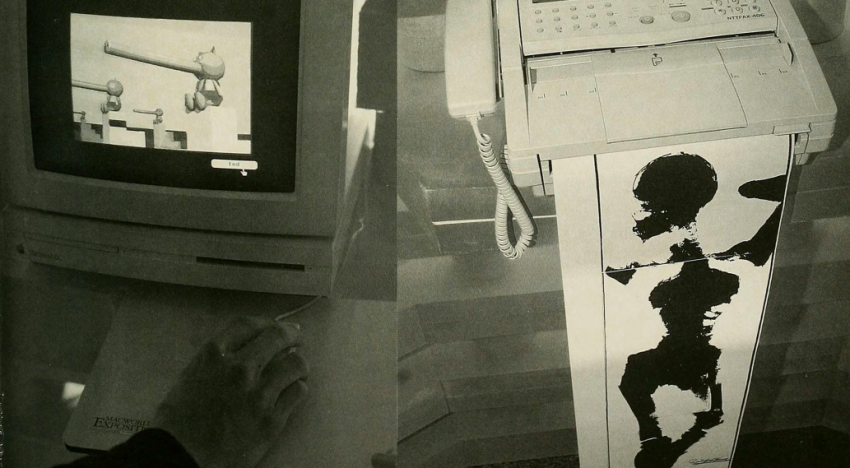

“The works and messages from almost 100 artists, writers, and cultural figures were available through five channels,” says Monoskop, where you can download The Museum Inside the Telephone Network’s catalog (also available in high resolution). “The works in ‘Voice & sound channel’ such as talks and readings on the theme of communication could be listened to by telephone. The ‘Interactive channel’ offered participants to create musical tunes by pushing buttons on a telephone. Works of art, novels, comics and essays could be received at home through ‘Fax channel.’ The ‘Live channel’ offered artists’ live performances and telephone dialogues between invited intellectuals to be heard by telephone. Additionally, computer graphics works could be accessed by modem and downloaded to one’s personal computer screen for viewing.”

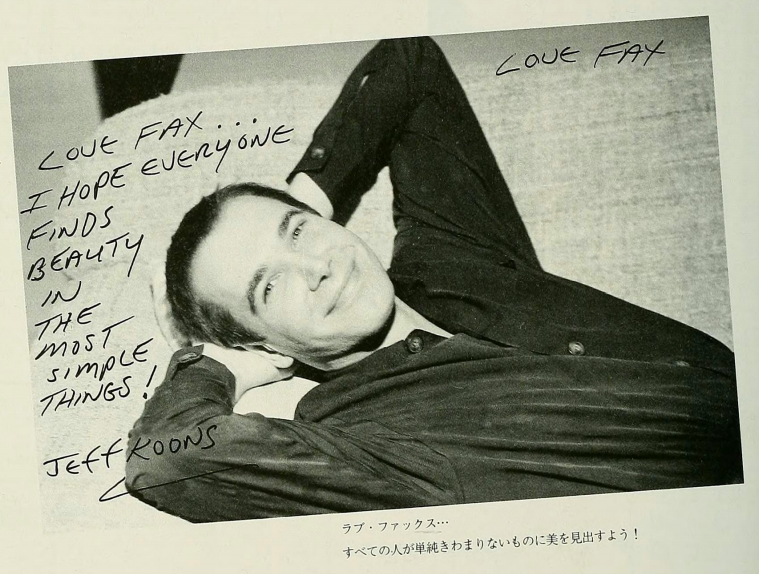

“We need to recognize honestly that there were numerous problems with The Museum Inside the Telephone Network,” writes curator and critic Asada Akira in the catalog’s introduction. “Neither the preparation time nor the means for carrying it out was sufficient. Thus there were not a few creative artists whose participation would have been a great asset to the project, but whom we were forced to do without.” Yet its list of contributors, which still reads like a Who’s-Who of the avant-garde and otherwise adventurous creators of the day, includes architects like Isozaki Arata and Renzo Piano, musicians like Laurie Anderson and Sakamoto Ryuichi, directors like Kurosawa Kiyoshi and Derek Jarman, writers like William S. Burroughs and J.G. Ballard, composers like John Cage and Philip Glass, choreographers like William Forsythe, Merce Cunningham, and visual artists like Yokoo Tadanori and Jeff Koons.

The Museum Inside the Telephone Network launched as the first venture of NTT’s InterCommunication Center (ICC), a “21st-century museum that will provide interface between science and technology and art and culture in the coming electronic age,” as Asada described it in 1991. Having recently celebrated its 20th year open in Tokyo’s Opera City Tower, the ICC continues to put on a variety of non-virtual exhibitions very much in the spirit of the original, and involving some of the very same artists as well (as of this writing, they’re readying a music installation co-created by Sakamoto). But offline or on, any union of art and technology is only as interesting as the spirit motivating it, and the creators of such projects would do well to keep in mind the words of The Museum Inside the Telephone Network contributor Kondou Kouji: “I hope that people will think of this as the experience of accidentally drifting into a telephone network, wherein awaits a vast world of pleasure and fun.”

Related Content:

Take a Virtual Tour of the 1913 Exhibition That Introduced Avant-Garde Art to America

Take a Virtual Reality Tour of the World’s Stolen Art

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

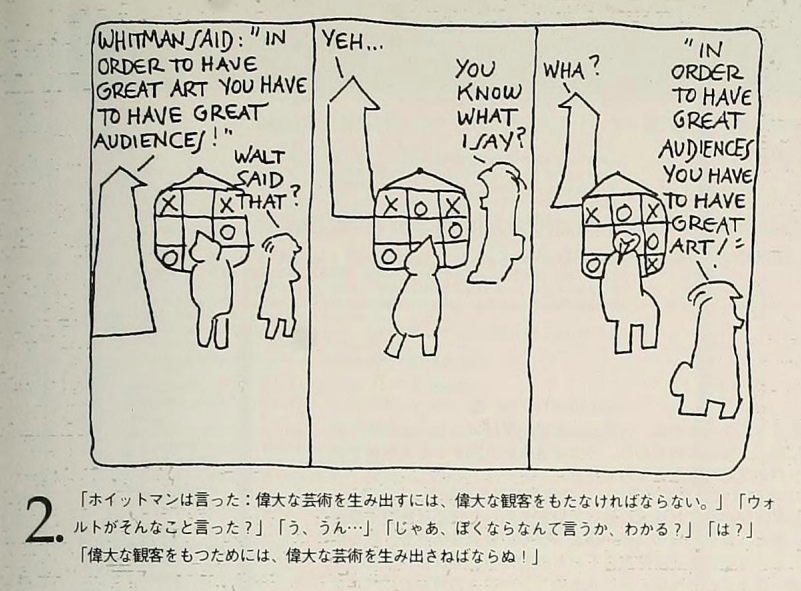

Read More...Watch “Alike,” a Poignant Short Animated Film About the Enduring Conflict Between Creativity and Conformity

From Barcelona comes “Alike,” a short animated film by Daniel Martínez Lara and Rafa Cano Méndez. Made with Blender, an open-source 3D rendering program, “Alike” has won a heap of awards and clocked an impressive 10 million views on Youtube and Vimeo. A labor of love made over four years, the film revolves around this question: “In a busy life, Copi is a father who tries to teach the right way to his son, Paste. But … What is the correct path?” To find the answer, they have to let a drama play out. Which will prevail? Creativity? Or conformity? It’s an internal conflict we’re all familiar with.

Watch the film when you’re not in a rush, when you have seven unburdened minutes to take it in. “Alike” will be added to our list of Free Animations, a subset of our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

The Employment: A Prize-Winning Animation About Why We’re So Disenchanted with Work Today

Bertrand Russell & Buckminster Fuller on Why We Should Work Less, and Live & Learn More

Charles Bukowski Rails Against 9‑to‑5 Jobs in a Brutally Honest Letter (1986)

William Faulkner Resigns From His Post Office Job With a Spectacular Letter (1924)

Read More...Beautiful & Outlandish Color Illustrations Let Europeans See Exotic Fish for the First Time (1754)

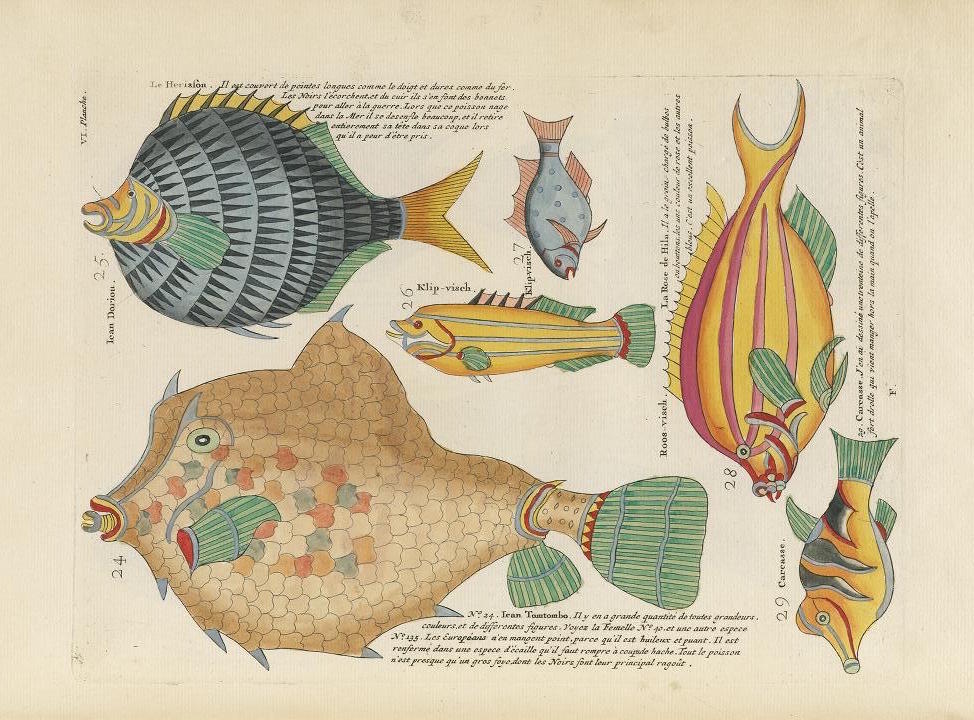

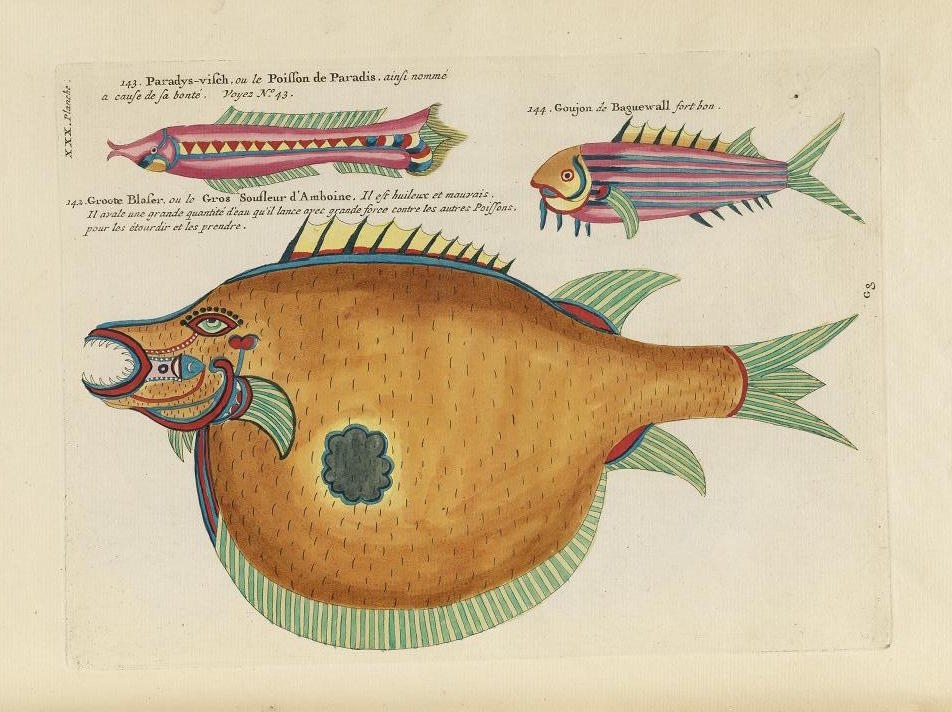

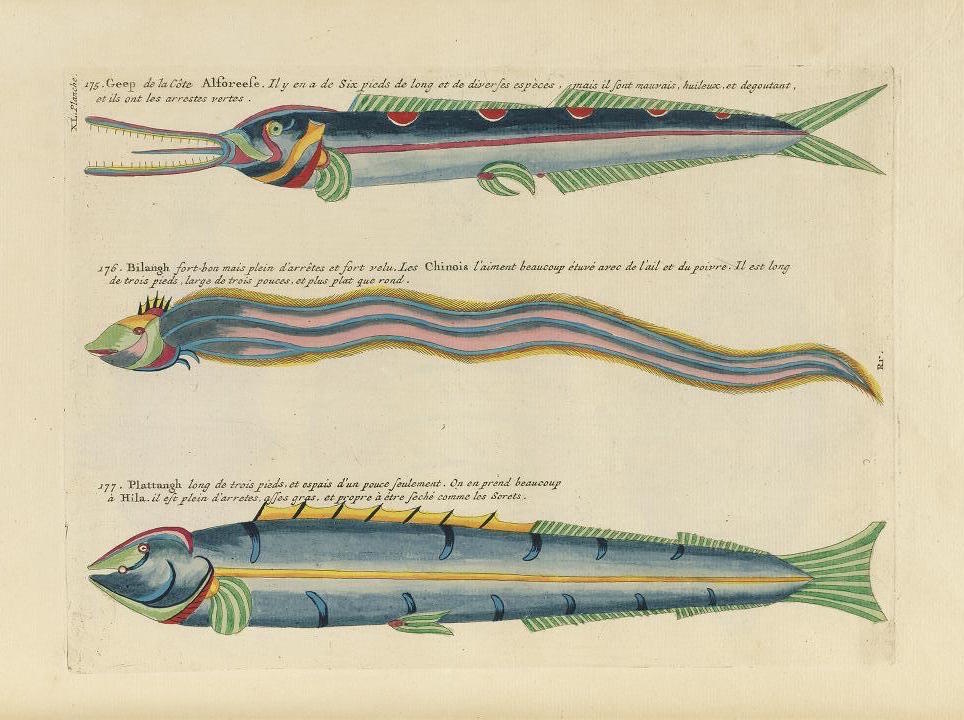

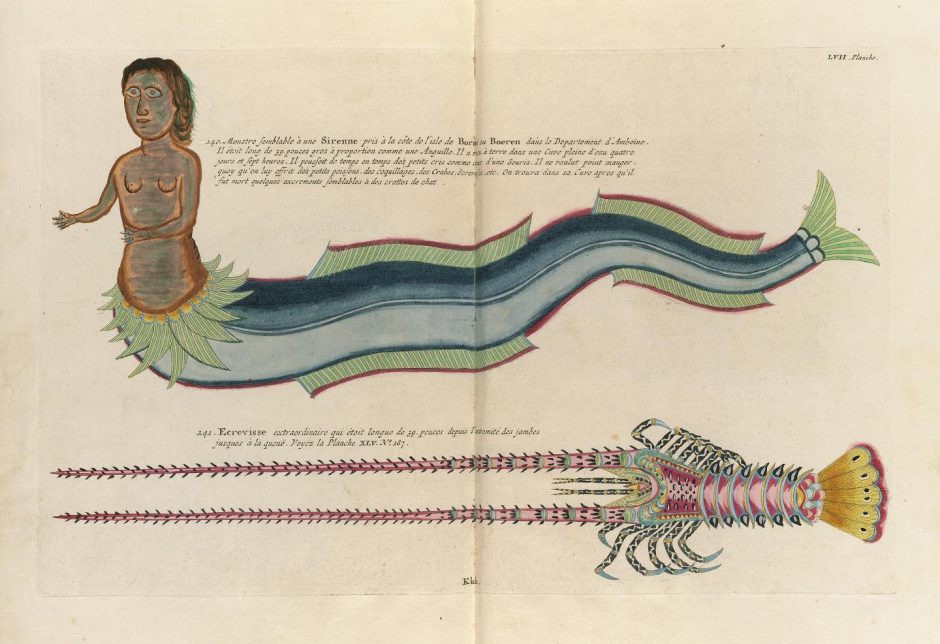

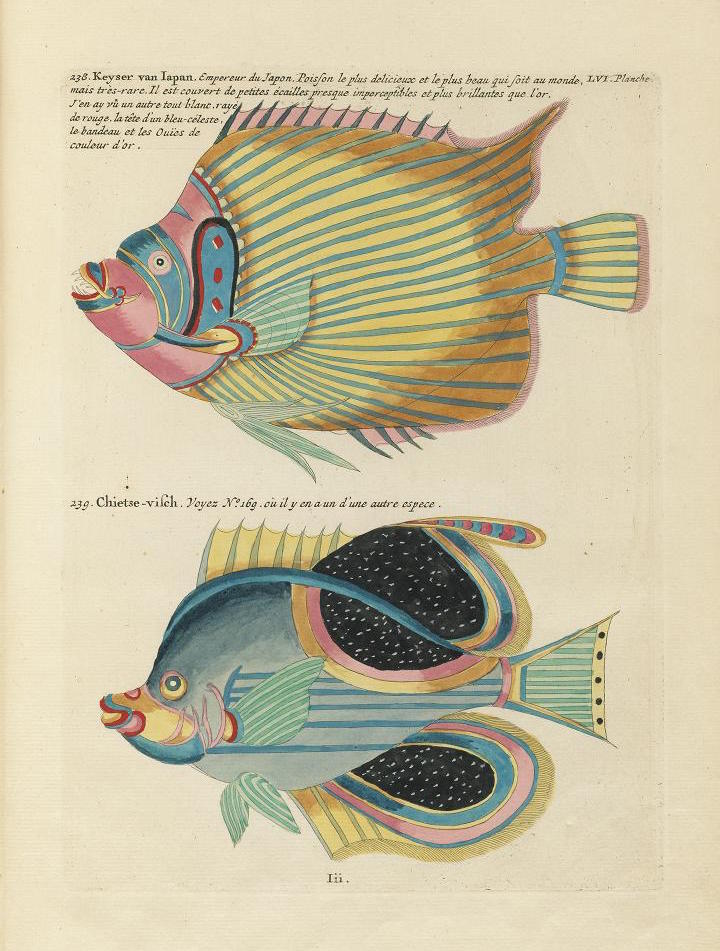

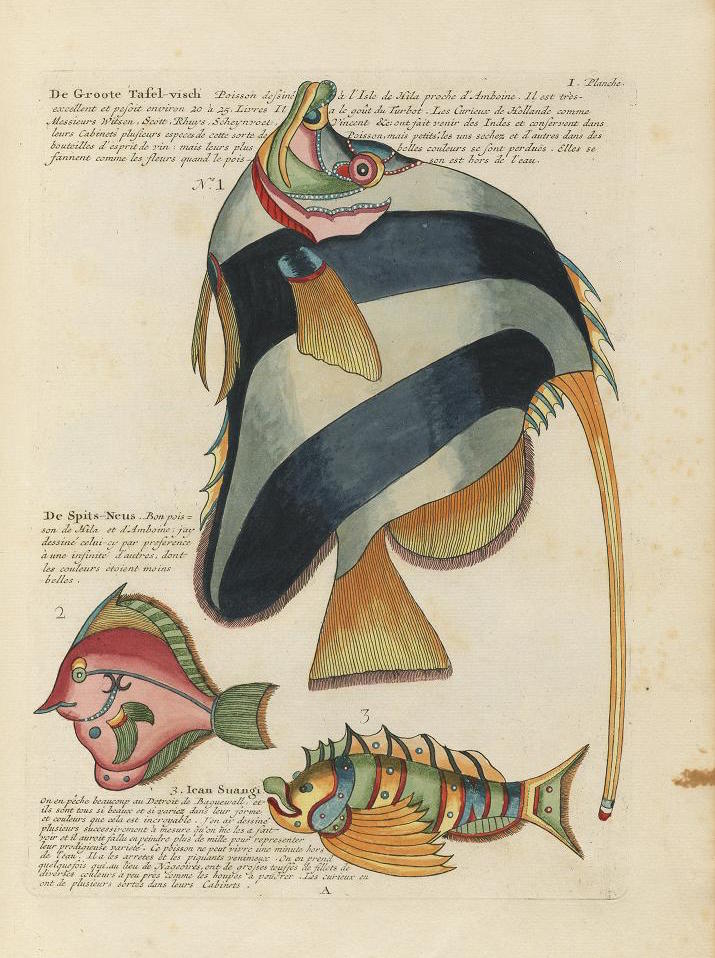

Whether in the tanks into which we gaze at the aquarium or the CGI-intensive wildlife-based gagfests at which we gaze in the theater, most of us in the 21st century have seen more than a few funny fish. Eighteenth-century Europeans couldn’t have said the same. The great majority passed their entire lives without so much as a glance at the form of even one live exotic creature of the deep, and most of those who have a sense of what such a sight looked like probably got it from an illustration. But even so, some of the illustrated fish of the day must have proven unforgettable, especially the ones in Louis Renard’s Poissons, Ecrevisses et Crabes.

First published in 1719 with a second edition, seen here, in 1754, Renard’s book, whose full title translates to Fishes, Crayfishes, and Crabs, of Diverse Colors and Extraordinary Form, that Are Found Around the Islands of the Moluccas and on the Coasts of the Southern Lands, showed its readers, in full color for the very first time, creatures the likes of which they’d never have had occasion even to imagine. The book’s 460 hand-colored copper engravings depict, according to the Glasgow University Library, “415 fishes, 41 crustaceans, two stick insects, a dugong and a mermaid.”

The specimens in the first part of the book tend toward the realistic, while those of the second “verge on the surreal,” many of which “bear no similarity to any living creatures,” some of which bear “small human faces, suns, moons and stars” on their flanks and carapaces, most possessed of colors “applied in a rather arbitrary fashion,” though brilliantly so. In the short accompanying texts, “several of the fish” — presumably not the mermaid — “are assessed in terms of their edibility and are accompanied by brief recipes.”

Renard himself, who lived from 1678 to 1746, seems to have had a career as colorful as the fish in his book. “As well as spending some seventeen years as a publisher and bookdealer,” he also “sold medicines, brokered English bonds and, more intriguingly, acted as a spy for the British Crown, being employed by Queen Anne, George I and George II.” Far from keeping that part of his life a secret, “Renard used his status as an ‘agent’ to help advertise his books. This particular work is actually dedicated to George I while the title-page describes the publisher as ‘Louis Renard, Agent de Sa Majesté Britannique.’ ”

You can behold more of Poissons, Ecrevisses et Crabes at the Public Domain Review. “If the illustrations are breathtaking to us now, with all the hours of David Attenborough documentaries under our belts,” they write, “one can only imagine the impact this would have had on a European audience of the eighteenth century, to which the exotic ocean life of the East would have been virtually unknown.”

Though received as a respectable scientific work in its day — and even, as the Glasgow University Library puts it, “a product of the Enlightenment” — the book now stands as an enchanting tribute to the combination of a little knowledge and a lot of human imagination.

Related Content:

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...How a Korean Potter Found a “Beautiful Life” Through His Art: A Short, Life-Affirming Documentary

I like to think I appreciate all aspects of the culture of South Korea, where I live, but different attractions bring different foreigners here. Some come for the food, some come for the music (pop, traditional, or somewhere in between), some come for the medical tourism. Others, like British ceramicist Roger Law, come for the pottery. The half-hour documentary above will give you an idea of what makes Korean pottery, and the Korean potters who craft it, so distinctive, taking viewers into the workshop of Lee Kang-hyo, who has become famous by there bringing together the distinct traditions of onggi glazed earthenware pottery and buncheong white slip decoration.

“As a high school student, I asked myself some fundamental questions,” says Lee in voiceover as we watch him beat the clay of what looks more and more like a large jar into shape. “What would be good to do for a living? What is my best talent? How can I enjoy a life of peace? It was then I decided to become an artist.” As he creates, he tells us about the long history of pottery in Korea and his experience practicing and mastering the traditions in which he works. Looked at onggi, he says, “I never thought they were simply big jars. I thought they were great sculpture.”

“My documentary tells the story of Lee Kang-hyo’s search for a beautiful life, through his work with clay and the love of his family,” says director Alex Wright, a story that “gives an insight into the spiritual journey that plays a vital part in his artistic practice.” For Lee, this had to do as much with the heart and mind as with the hand, loosening up and lightening up even as he grew more skilled, a realization that first occurred when he became friendly with Japanese master potter Koie Ryoji. “Kang-hyo, why don’t you try to change your thinking?’ ” Lee remembers Koie asking after he presented him with his latest piece. “And he lifted it up and crushed it. He said: ‘Form doesn’t always have to be straight. It can be beautiful.’ ”

That lesson holds in other cultural spheres as well. “Ceramic culture is very closely connected to dietary life and food culture,” Lee observes. “Korea has developed a fermented food culture. A lot of foods are fermented and stored, such as sauces and kimchi,” which might stay in their ceramic jars for years before consumption. And so “Korea has developed the skills to make big jars, more than any other country” with the “quickest and most perfect forms.” This might sound like the makings of a rustic, utilitarian pottery — and indeed cuisine — but in fact the work of Lee and other Korean masters increasingly aligns with the growing global taste for things outwardly simple but inwardly refined. In that particular sensibility, whether expressed as pottery or food or music or anything else, Korea might well lead the world.

Lee Kang-hyo ‘Onggi Master will be added to our collection of Free Documentaries, a subset of our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related content:

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...What Makes a David Lynch Film Lynchian: A Video Essay

As soon as it began airing on ABC in the early 1990s, Twin Peaks got us wondering where its distinctively resonant oddness, never before felt on the airwaves of prime-time television, could have come from. Some viewers had already seen co-creator David Lynch’s films Eraserhead and Blue Velvet and may thus have had a more developed feel for it, but for everyone else the nature and origin of the “Lynchian” — as critics soon began labeling it — remained utterly mysterious. Now, with the long-awaited Twin Peaks: The Return having completed its own run, we’ve started thinking about it once again.

What does the Lynchian look like from the vantage of the 21st century? David Foster Wallace, in an essay on Lynch’s Lost Highway twenty years ago, defined the term “Lynchian” as referring to “a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former’s perpetual containment within the latter.” Lewis Bond, the video essayist who runs the Youtube channel Channel Criswell, goes a bit deeper in “David Lynch — The Elusive Subconscious.” What is it, he asks, that denotes the style of Lynch? “The same way a hallway sinking into darkness is Lynchian, so is a white picket fence in a slice of Americana.”

These and the enormous variety of other things Lynchian must “exude elusiveness, and the enigma of what signifies Lynchian sensibilities lies in producing unfamiliarity in that which was once familiar.“At first glance, that statement may seem as obscure as some of Lynch’s creative choices do when you first witness them. But spend a few minutes with Bond’s wide-ranging video essay, taking in Lynch’s images at the same time as the analysis, and you’ll get a clearer sense of what both of them are going for. After examining Lynch’s use of the subconscious in his films from several different angles, Bond arrives at Pauline Kael’s description of the filmmaker as “the first populist surrealist.”

“Although his work is puzzling, and more often than not intended to be so,” says Bond, Lynch “still manages to strike a chord with the way we feel.” Lynch, in other words, puts dreams on the screen, but instead of simply relating the inventions of his own subconscious — hearing someone retell their dreams being, after all, a byword for an agonizingly boring experience — he somehow gets all of us to dream them ourselves. What haunts us when we wake up after a particularly harrowing night also haunts us when we come out of a Lynch movie, but the artistry of the latter has a way of making us want to plunge right back into the nightmare again.

Related Content:

Watch an Epic, 4‑Hour Video Essay on the Making & Mythology of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks

An Animated David Lynch Explains Where He Gets His Ideas

What Does “Kafkaesque” Really Mean? A Short Animated Video Explains

What “Orwellian” Really Means: An Animated Lesson About the Use & Abuse of the Term

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...

China’s New Luminous White Library: A Striking Visual Introduction

MVRDV, a Dutch architecture and urban design firm, teamed up with Chinese architects to create the Tianjin Binhai Library, a massive cultural center featuring “a luminous spherical auditorium around which floor-to-ceiling bookcases cascade.” Located not far from Beijing, the library was built quickly by any standards. It took only three years to move from “the first sketch to the [grand] opening” on October 1. Elaborating on the library, which can house 1.2 million books, MVRDV notes:

The building’s mass extrudes upwards from the site and is ‘punctured’ by a spherical auditorium in the centre. Bookshelves are arrayed on either side of the sphere and act as everything from stairs to seating, even continuing along the ceiling to create an illuminated topography. These contours also continue along the two full glass facades that connect the library to the park outside and the public corridor inside, serving as louvres to protect the interior against excessive sunlight whilst also creating a bright and evenly lit interior.

The video above gives you a visual introduction to the building. And, on the MRDV website, you can view a gallery of photos that let you see the library’s shapely design.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

A Virtual Tour of Japan’s Inflatable Concert Hall

Read More...What the Future Sounded Like: Documentary Tells the Forgotten 1960s History of Britain’s Avant-Garde Electronic Musicians

It really is impossible to overstate the fact that most of the music around us sounds the way it does today because of an electronic revolution that happened primarily in the 1960s and 70s (with roots stretching back to the turn of the century). While folk and rock and roll solidified the sound of the present on home hi-fis and coffee shop and festival stages, the sound of the future was crafted behind studio doors and in scientific laboratories. What the Future Sounded Like, the short documentary above, transports us back to that time, specifically in Britain, where some of the finest recording technology developed to meet the increasing demands of bands like the Beatles and Pink Floyd.

Much less well-known are entities like the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop, whose crew of engineers and audio scientists made what sounded like magic to the ears of radio and television audiences. “Think of a sound, now make it,” says Peter Zinovieff “any sound is now possible, any combination of sounds is now possible.” Zinovieff, London-born son of an émigré Russian princess and inventor of the hugely influential VCS3 synthesizer in 1969, opens the documentary—fittingly, since his technology helped power the futuristic sound of progressive rock, and since, together with the Radiophonic Workshop’s Delia Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson, he ran Unit Delta Plus, a studio group that created and promoted electronic music.

Also appearing in the documentary is Tristram Cary, who, with Zinovieff, founded Electronic Music Studios, one of four makers of commercial synthesizers in the late sixties, along with ARP, Buchla, and Moog. Zinovieff and Carey are not household names in part because they didn’t particularly strive to be, preferring to work behind the scenes on experimental forms and eschewing popular music even as their technology gave birth to so much of it. The aristocratic Zinovieff and pipe-smoking, professorial Carey hardly fit in with the crowd of rock and pop stars they inspired.

In hindsight, however, Zinovieff desires more recognition for their work. “One thing which is odd, is that there’s a missing chapter, which is EMS, in all the books about electronic music. People do not know what incredible mechanical adventures we were up to.” Those adventures included not only creating new technology, but composing never-before-heard music. Both Zinovieff and Carey continue to create electronic scores, and Carey happens to be one of the first adopters in Britain of musique concrète, the proto-electronic music pioneered in the 1940s using tape machines, microphones, filters, and other recording devices, along with found sounds, field recordings, and ad hoc instruments made from non-instrument objects. (See examples of these techniques in the clip above from the 1979 BBC documentary The New Sound of Music.)

Many of the sounds that emerged from Britain’s electronic music founders came out of the detritus of World War II. Carey’s first serious studio design, he says, “coincided with the post-war appearance of an enormous amount of junk from the army, navy, and air force. For someone who knew what to do, and could handle a soldering iron, and could design audio equipment, even if you only had 30 shillings in your pocket, you could get something.” With their knowledge of electronics and hodge-podge of technology, Carey and his compatriots were designing an avant-garde electronic “high modernity,” author Trevor Pinch declares. “I think you can think of people like Tristan Carey as dreaming of a future soundscape of London.” Nowadays, those sounds are as familiar to us as the music piped over the speakers in restaurants and shops. One wonders what the future after the future these pioneers designed will sound like?

What the Future Sounded Like will be added to our collection of Documentaries, a subset of our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Two Documentaries Introduce Delia Derbyshire, the Pioneer in Electronic Music

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Read More...Yale Presents a Free Online Course on Miguel de Cervantes’ Masterpiece Don Quixote

Among the literary works that emerged in the so-called Golden Age of Spanish culture in the 16th and 17th centuries, one shines so brightly that it seems to eclipse all others, and indeed is said to not only be the foundation of modern Spanish writing, but of the modern novel itself. Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote synthesized the Medieval and Renaissance literature that had come before it in a brilliantly satirical work, writes popular academic Harold Bloom, with “cosmological scope and reverberation.” But in such high praise of a great work, we can lose sight of the work itself. Don Quixote is hardly an exception.

“The notion of ‘literary classic,’” Simon Leys writes at the New York Review of Books, “has a solemn ring about it. But Don Quixote, which is the classic par excellence, was written for a flatly practical purpose: to amuse the largest possible number of readers, in order to make a lot of money for the author (who needed it badly).” To mention these intentions is not to diminish the work, but perhaps even to burnish it further. To have created, as Yale’s Roberto González Echevarría says in his introductory lecture above, “one of the unquestioned masterpieces of world literature, let alone the Western Canon,” while seeking primarily to entertain and make a buck says quite a lot about Cervantes’ considerable talents, and, perhaps, about his modernism.

Rather than write for a feudal patron, monarch, or deity, he wrote for what he hoped would be a profitable mass-market. In so doing, says Professor González, quoting Gabriel García Márquez, Cervantes wrote “a novel in which there is already everything that novelists would attempt to do in the future until today.” González’s course, “Cervantes’ Don Quixote,” is now available online in a series of 24 lectures, available on YouTube and iTunes. (Stream all 24 lectures below.) You can download all of the course materials, including the syllabus and overview of each class, here. There is a good deal of reading involved, and you’ll need to get your hands on a few extra books. In addition to the weighty Quixote, “students are also expected to read four of Cervantes’ Exemplary Stories, Cervantes’ Don Quixote: A Casebook, and J.H. Elliott’s Imperial Spain.” It would seem well worth the effort.

Professor González goes on in his introduction to discuss the novel’s importance to such figures as Sigmund Freud, Jorge Luis Borges, and British scholar Ian Watt, who called Don Quixote “one of four myths of modern individualism, the others being Faust, Don Juan, and Robinson Crusoe.” The novel’s historical resume is tremendously impressive, but the most important thing about it, says González, is that it has been read and enjoyed by millions of people around the world for hundreds of years. Just why is that?

The professor quotes from his own introduction to the Penguin Classics edition he asks students to read in providing his answer: “Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra’s masterpiece has endured because it focuses on literature’s foremost appeal: to become another, to leave a typically embattled self for another closer to one’s desires and aspirations. This is why Don Quixote has often been read as a children’s book, and continues to be read by and to children.” Critics might be prone to dismiss such enjoyable wish fulfilment as trivial, but the centuries-long success of Don Quixote shows it may be the foundation of all modern literary writing.

Don Quixote will be added to our collection of Free Online Literature courses, a subset of our larger collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

Related Content:

Gustave Doré’s Exquisite Engravings of Cervantes’ Don Quixote

Free Online Literature Courses

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

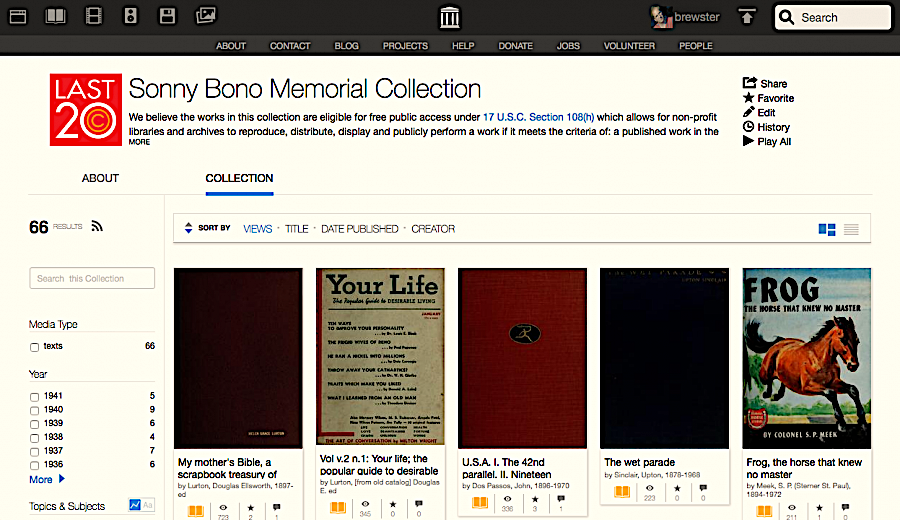

Read More...The Internet Archive “Liberates” Books Published Between 1923 and 1941, and Will Put 10,000 Digitized Books Online

Here at Open Culture, we can never resist the chance to feature books free to read and download online. Books can become free in a number of different ways, one of the most reliable being reversion to the public domain after a certain amount of time has passed since its publication — usually a long time, with the result that the average age of the books freely available online skews quite old. Nothing wrong with old or even ancient reading material, of course, but sometimes one wishes copyright law didn’t put quite such a delay on the process. The Internet Archive and its collaborators have recently made progress in that department, finding a legal means of “liberating” books of a less distant vintage than usual.

“The Internet Archive is now leveraging a little known, and perhaps never used, provision of US copyright law, Section 108h, which allows libraries to scan and make available materials published [from] 1923 to 1941 if they are not being actively sold,” writes the site’s founder Brewster Kahle.

Tulane University copyright scholar Elizabeth Townsend Gard and her students “helped bring the first scanned books of this era available online in a collection named for the author of the bill making this necessary: The Sonny Bono Memorial Collection.” Yes, that Sonny Sono, who after his music career (most memorably as half of Sonny and Cher) served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1994 until his death in 1998.

At the moment, the Sonny Bono Memorial Collection offers such 94-to- 76-year-old pieces of reading material as varied as André Malraux’s The Royal Way, Arnold Dresden’s An Invitation to Mathematics, René Kraus’ Winston Churchill: A Biography, Colonel S.P. Meek’s Frog, the Horse that Knew No Master, and Donald Henderson Clarke’s Impatient Virgin. Kahle assures us that “We will add another 10,000 books and other works in the near future,” and reminds us that “if the Founding Fathers had their way, almost all works from the 20th century would be public domain by now.” The intentions of the Founding Fathers may matter to you or they may not, but if you’re an Open Culture reader, you can hardly quibble with the new availability of dozens of free books online — and the prospect of thousands more soon to come. Stay tuned and watch the collection grow.

Related Content:

800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices

2,000+ Architecture & Art Books You Can Read Free at the Internet Archive

Download 200+ Free Modern Art Books from the Guggenheim Museum

Free: You Can Now Read Classic Books by MIT Press on Archive.org

British Library to Offer 65,000 Free eBooks

74 Free Banned Books (for Banned Books Week)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...