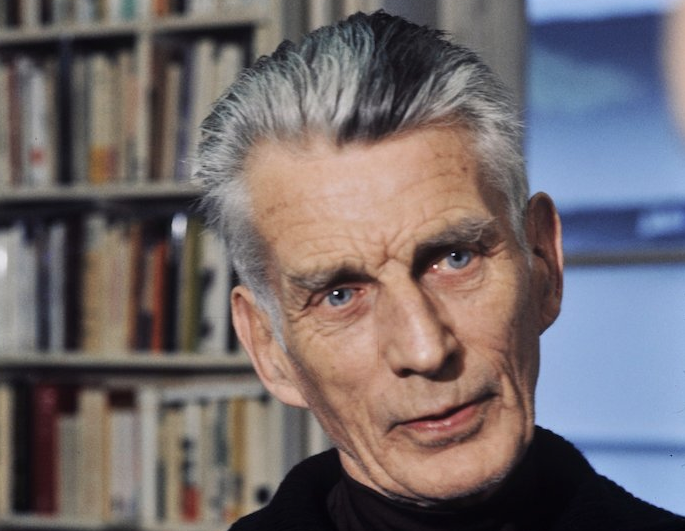

“Try Again. Fail Again. Fail Better”: How Samuel Beckett Created the Unlikely Mantra That Inspires Entrepreneurs Today

Image by the Bibliothèque nationale de France, via Wikimedia Commons

To what writer, besides Ayn Rand, do the business-minded techies and tech-minded businessmen of 21st-century Silicon Valley look for their inspiration? The name of Samuel Beckett may not, at first, strike you as an obvious answer — unless, of course, you know the origin of the phrase “Fail better.” It appears five times in Beckett’s 1983 story “Worstward Ho,” the first of which goes like this: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” The sentiment seems to resonate naturally with the mentality demanded by the world of tech startups, where nearly every venture ends in failure, but failure which may well contain the seeds of future success.

Or rather, the apparent sentiment resonates. “By itself, you can probably understand why this phrase has become a mantra of sorts, especially in the glamorized world of overworked start-up founders hoping against pretty high odds to make it,” writes Books on the Wall’s Andrea Schlottman.

“We think so, too. That is, until you read the rest of it.” The paragraph immediately following those much-quoted lines runs as follows:

First the body. No. First the place. No. First both. Now either. Now the other. Sick of the either try the other. Sick of it back sick of the either. So on. Somehow on. Till sick of both. Throw up and go. Where neither. Till sick of there. Throw up and back. The body again. Where none. The place again. Where none. Try again. Fail again. Better again. Or better worse. Fail worse again. Still worse again. Till sick for good. Throw up for good. Go for good. Where neither for good. Good and all.

“Throw up for good” — a rich image, certainly, but perhaps not as likely to get you out there disrupting complacent industries as “Fail better,” which The New Inquiry’s Ned Beauman describes as “experimental literature’s equivalent of that famous Che Guevara photo, flayed completely of meaning and turned into a successful brand with no particular owner. ‘Worstward Ho’ may be a difficult work that resists any stable interpretation, but we can at least be pretty sure that Beckett’s message was a bit darker than ‘Just do your best and everything is sure to work out ok in the end.’

But if Beckett’s words don’t provide quite the cause for optimism we thought they did, the story of his life actually might. “Beckett had already experienced plenty of artistic failure by the time he developed it into a poetics,” writes Chris Power in The Guardian. “No one was willing to publish his first novel, Dream of Fair to Middling Women, and the book of short stories he salvaged from it, More Pricks Than Kicks (1934), sold disastrously.” And yet today, even those who’ve never read a page of his work — indeed, those who’ve never even read the “Fail better” quote in full — acknowledge him as one of the 20th century’s greatest literary masters. Still, we have good cause to believe that Beckett himself probably regarded his own work as, to one degree or another, a failure. Those of us who revere it would do well to remember that, and maybe even to draw some inspiration from it.

Related Content:

Start Your Day with Werner Herzog Inspirational Posters

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Why Incompetent People Think They’re Amazing: An Animated Lesson from David Dunning (of the Famous “Dunning-Kruger Effect”)

The business world has long had special jargon for the Kafkaesque incompetence bedeviling the ranks of upper management. There is “the Peter principle,” first described in a satirical book of the same name in 1968. More recently, we have the positive notion of “failing upward.” The concept has inspired a mantra, “fail harder, fail faster,” as well as popular books like The Gift of Failure. Famed research professor, author, and TED talker Brené Brown has called TED “the failure conference,” and indeed, a “FailCon” does exist, “in over a dozen cities on 6 continents around the globe.”

The candor about this most unavoidable of human phenomena may prove a boon to public health, lowering levels of hypertension by a significant margin. But is there a danger in praising failure too fervently? (Samuel Beckett’s quote on the matter, beloved by many a 21st century thought leader, proves decidedly more ambiguous in context.) Might it present an even greater opportunity for people to “rise to their level of incompetence”? Given the prevalence of the “Dunning-Kruger Effect,” a cognitive bias explained by John Cleese in a previous post, we may not be well-placed to know whether our efforts constitute success or failure, or whether we actually have the skills we think we do.

First described by social psychologists David Dunning (University of Michigan) and Justin Kruger (N.Y.U.) in 1999, the effect “suggests that we’re not very good at evaluating ourselves accurately.” So says the narrator of the TED-Ed lesson above, scripted by Dunning and offering a sober reminder of the human propensity for self-delusion. “We frequently overestimate our own abilities,” resulting in widespread “illusory superiority” that makes “incompetent people think they’re amazing.” The effect greatly intensifies at the lower end of the scale; it is often “those with the least ability who are most likely to overrate their skills to the greatest extent.” Or as Cleese plainly puts it, some people “are so stupid, they have no idea how stupid they are.”

Combine this with the converse effect—the tendency of skilled individuals to underrate themselves—and we have the preconditions for an epidemic of mismatched skill sets and positions. But while imposter syndrome can produce tragic personal results and deprive the world of talent, the Dunning-Kruger effect’s worst casualties affect us all adversely. People “measurably poor at logical reasoning, grammar, financial knowledge, math, emotional intelligence, running medical lab tests, and chess all tend to rate their expertise almost as favorably as actual experts do.” When such people get promoted up the chain, they can unwittingly do a great deal of harm.

While arrogant self-importance plays its role in fostering delusions of expertise, Dunning and Kruger found that most of us are subject to the effect in some area of our lives simply because we lack the skills to understand how bad we are at certain things. We don’t know the rules well enough to successfully, creatively break them. Until we have some basic understanding of what constitutes competence in a particular endeavor, we cannot even understand that we’ve failed.

Real experts, on the other hand, tend to assume their skills are ordinary and unremarkable. “The result is that people, whether they’re inept or highly skilled, are often caught in a bubble of inaccurate self-perception.” How can we get out? The answers won’t surprise you. Listen to constructive feedback and never stop learning, behavior that can require a good deal of vulnerability and humility.

Related Content:

The Power of Empathy: A Quick Animated Lesson That Can Make You a Better Person

Free Online Psychology & Neuroscience Courses

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...The Van Gogh of Microsoft Excel: How a Japanese Retiree Makes Intricate Landscape Paintings with Spreadsheet Software

Just when you thought you’ve mastered Microsoft Excel–creating pivot tables, VLOOKUPs and the rest–you discover the feature you never knew was there. The one that lets you create Japanese landscape paintings. When Tatsuo Horiuchi retired, he found that feature and leaned on it, hard. Now 77 years old, he has enough landscape paintings to stage an exhibition–all made with the point and click of a mouse.

So what’s the moral of this story? Maybe it’s you’re never too old to make art. Or maybe it’s never too late to master those hidden features and push technology to the bleeding edge. In Tatsuo’s case, he’s doing both.

Related Content:

The Art of Hand-Drawn Japanese Anime: A Deep Study of How Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira Uses Light

A Hypnotic Look at How Japanese Samurai Swords Are Made

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

Read More...How Scientology Works: A Primer Based on a Reading of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Film, The Master

Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master focuses, with almost unbearable intensity, on two characters: Joaquin Phoenix’s impulsive ex-sailor Freddie Quell, and Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Lancaster Dodd, “the founder and magnetic core of the Cause — a cluster of folk who believe, among other things, that our souls, which predate the foundation of the Earth, are no more than temporary residents of our frail bodily housing,” writes The New Yorker’s Anthony Lane in his review of the film. “Any relation to persons living, dead, or Scientological is, of course, entirely coincidental.”

Before The Master came out, rumor built up that the film mounted a scathing critique of the Church of Scientology; now, we know that it accomplishes something, par for the course for Anderson, much more fascinating and artistically idiosyncratic.

Few of its gloriously 65-millimeter-shot scenes seem to have much to say, at least directly, about Scientology or any other system of thought. But perhaps the most memorable, in which Dodd, having discovered Freddie stown away aboard his chartered yacht, offers him a session of “informal processing,” does indeed have much to do with the faith founded by L. Ron Hubbard — at least if you believe the analysis of Evan Puschak, better known as the Nerdwriter, who argues that the scene “bears an unmistakable reference to a vital activity within Scientology called auditing.”

Just as Dodd does to Freddie, “the auditor in Scientology asks questions of the ‘preclear’ with the goal of ridding him of ‘engrams,’ the term for traumatic memory stored in what’s called the ‘reactive mind.’ ” By thus “helping the preclear relive the experience that caused the trauma,” the auditor accomplishes a goal that, in a clip Puschak includes in the essay, Hubbard lays out himself: to “show a fellow that he’s mocking up his own mind, therefore his own difficulties; that he is not completely adrift in, and swamped by, a body.” Scientological or not, such notions do intrigue the desperate, drifting Freddie, and although the story of his and Dodd’s entwinement, as told by Anderson, still divides critical opinion, we can say this for sure: it beats Battlefield Earth.

Related Content:

When William S. Burroughs Joined Scientology (and His 1971 Book Denouncing It)

Space Jazz, a Sonic Sci-Fi Opera by L. Ron Hubbard, Featuring Chick Corea (1983)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...A Salute to Every Frame a Painting: Watch All 28 Episodes of the Finely-Crafted (and Now Concluded) Video Essay Series on Cinema

Documentaries about film itself have existed for decades, but only with the advent of short-form internet video — preceded by the advents of powerful desktop editing software and high-quality home-video formats — did the form of the cinema video essay that we know today emerge. Over the past few years, the Youtube channel Every Frame a Painting has become one of the modern cinema video essay’s most respected purveyors, examining everything from how editors think to the bland music of superhero films to why Vancouver never plays itself to the signature technique of auteurs like Martin Scorsese, Jackie Chan, and, yes, Michael Bay.

Alas, Every Frame a Painting has come to an end. “When we started this YouTube project, we gave ourselves one simple rule: if we ever stopped enjoying the videos, we’d also stop making them,” says series co-creator Taylor Ramos. “And one day, we woke up and felt it was time.”

She says it in the never-produced script for a concluding episode, a text that takes us on a journey from Every Frame a Painting’s inception — born, as co-creator Tony Zhou puts it, out of frustration at having to “discuss visual ideas with non-visual people” — through its evolution into a series about film form rather than content (“most YouTube videos seemed to focus on story and character, so we went in the opposite direction”) to its conclusion.

Just as Every Frame a Painting’s episodes reveal to us how movies work, this final script reveals to us how Every Frame a Painting works — or more specifically, what factors led to its video essays looking and feeling like they do. “Nearly every stylistic decision you see about the channel ‚” Zhou says by way of giving one example, “was reverse-engineered from YouTube’s Copyright ID,” trying to find ways around the platform’s automatic copyright-violation detection system that would occasionally reject even the kind of fair use they were doing. Other choices they made more deliberately, such as to do old-fashioned library research whenever possible. “It’s very tempting to use Google because it’s so quick and it’s right there,” says Zhou in a much-highlighted passage, “but that’s exactly why you shouldn’t go straight to it.”

Whatever the origins of Zhou and Ramos’ rigorous process, it has ended up producing a series greatly appreciated by filmgoers and filmmakers alike. Binge-watch all 28 of Every Frame a Painting’s episodes (up top)— which will explain to you dramatic struggle as seen in The Silence of the Lambs, how the movies have depicted texting, the cinematic possibilities of the chair, and much more besides — and you’ll end up with, at the very least, an equivalent of a few semesters of film-school education. And maybe, just maybe, you’ll come away with the idea for a cinema video essay series of your own.

Related Content:

Buster Keaton: The Wonderful Gags of the Founding Father of Visual Comedy

How Orson Welles’ F for Fake Teaches Us How to Make the Perfect Video Essay

Vancouver Never Plays Itself

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

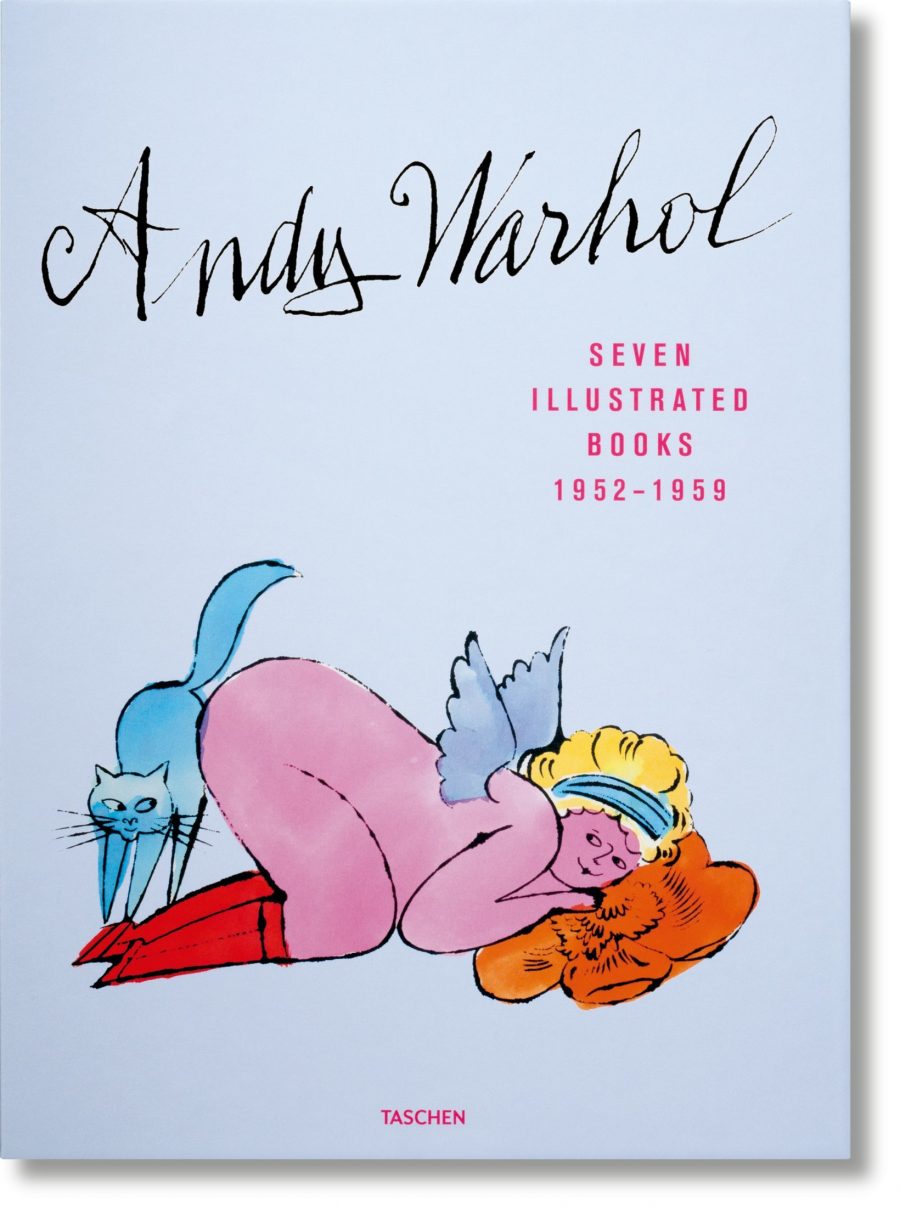

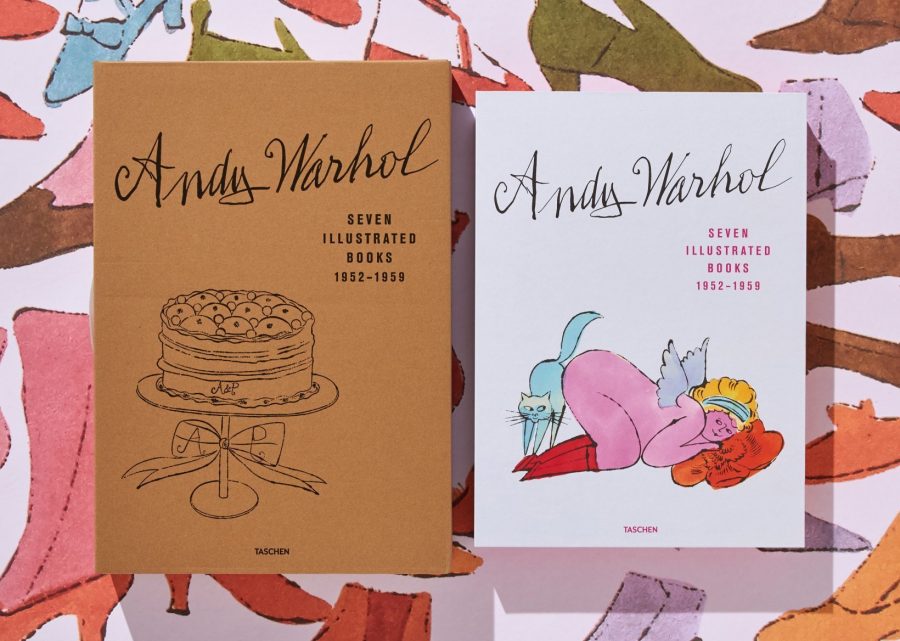

Read More...Andy Warhol’s Seven Hand-Illustrated Books: Charming, Little-Known, and Now Available to the World (1952–1959)

Got a knack for drawing, painting, sculpting, creating handmade objects of any kind? You’re maybe more likely to monetize your skill—with an Etsy or Pinterest account, for example—than move to New York and try to make a go of it. Were such convenient means of setting up shop available in the late 40’s, when Andy Warhol studied art education and commercial art at the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University, respectively, one wonders whether the often bedridden, introverted artist might have found it more appealing to work from home in Pittsburgh, and stay there.

Instead, he moved to New York and became a successful commercial artist by using his illustration skills to market himself. Before he was a “bellwether of post-war and contemporary art” with those famous silkscreen paintings in the 60s; before he made those famous films, discovered (and invented the concept of) art stars, and managed the Velvet Underground, Warhol created seven handmade books “as part of his strategy to woo clients and forge friendships.” So writes Taschen books, who have collected and reprinted Warhol’s art books in a single edition. (Five of the seven have never before been republished.)

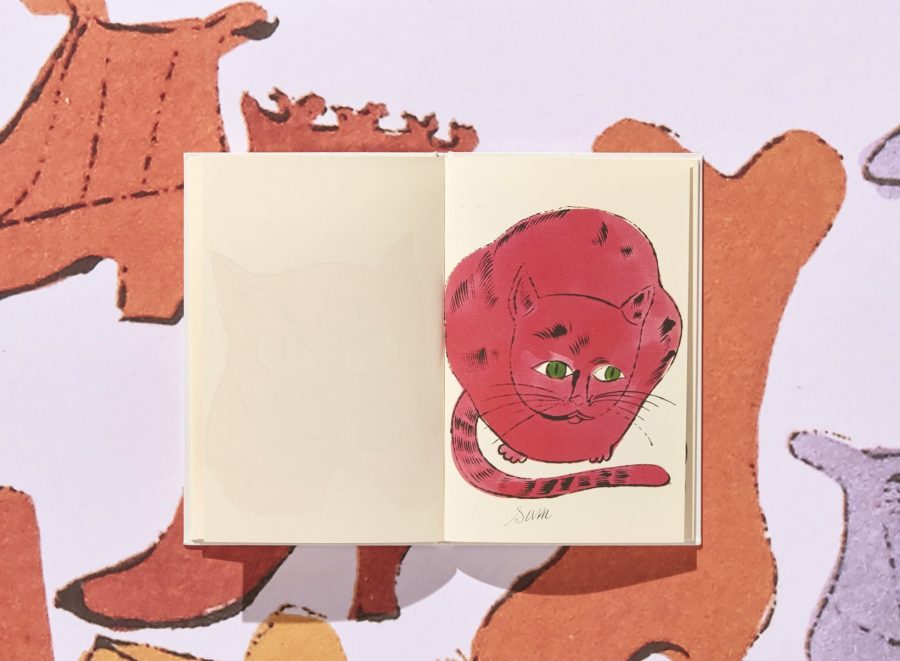

Warhol reserved the signature books for “his most valued contacts. These featured personal, unique drawings and quirky texts revealing his fondness for—among other subjects—cats, food, myths, shoes, beautiful boys, and gorgeous girls.”

They are intimate and charming, showing a side of the artist we don’t often see—but one we do see of so many contemporary illustrators. His hand-drawn illustrations have a very 21st century feel to them in their obsession with cats, cakes, fashion, and happy, nude zaftig beauties. Created between 1952 and 59, they could have come from any number of illustration or design sites. It’s easy to imagine a current-day Warhol making a living selling work like this online.

Had he been able to do so, might he have become a different kind of artist entirely? It’s impossible to say. I can imagine a number of people for whom I might buy copies of Love Is a Pink Cake, 25 Cats Named Sam, or À la Recherche du Shoe Perdu, as a holiday gift. But Warhol didn’t make copies of these books. He saved the mass production for his later gallery work. Instead the handmade calling cards remain “little-known, much-coveted jewels in the Warhol crown,” early examples of “the artists’ off-the-wall character as well as his accomplished draftsmanship, boundless creativity, and innuendo-laced humor.”

You might not know it from canvases like Eight Elvises, the Marilyn Monroe series, or Campbell’s Soup Cans, but Warhol had a particular talent for light, whimsical hand-drawn illustration. It’s a side of himself he showed few people once he became the Andy Warhol most of us know. Thanks to Taschen’s new book, a recent gallery showing of Warhol’s drawings, a 2012 Chronicle collection of his quirky illustrations from the 50s, and, well, Pinterest, it’s a side of him that can now belong to everyone.

You can now get your own copy of Andy Warhol: Seven Illustrated Books 1952–1959.

Related Content:

The Big Ideas Behind Andy Warhol’s Art, and How They Can Help Us Build a Better World

Short Film Takes You Inside the Recovery of Andy Warhol’s Lost Computer Art

Miyazaki Meets Warhol in Campbell’s Soup Cans Reimagined by Designer Hyo Taek Kim

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...The Robots of Your Dystopian Future Are Already Here: Two Chilling Videos Drive It All Home

A year ago, Boston Dynamics released a video showing its humanoid robot “Atlas” doing, well, rather human things–opening doors, walking through a snowy forest, hoisting cardboard boxes, and lifting itself off of the ground. Rarely has something so banal seemed so peculiar.

What is “Atlas” doing these days? As shown in this newly-released video above, it’s jumping to new heights, twisting in the air, and doing backflips with uncanny ease. Standing six feet tall and weighing 180 pounds, Atlas was designed to take care of mundane problems–like assisting emergency services in search and rescue operations and “operating powered equipment in environments where humans could not survive.” But that’s not where the applications of Atlas end. Seeing that the Pentagon has helped finance and design Atlas, you can easily see the humanoid fighting on the battlefield. Stay tuned for that clip in 2018.

Which brings us to our next video. The new short film, “Slaughterbots,” comes from the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots and it follows this plot:

A military firm unveils a tiny drone that hunts and kills with ruthless efficiency. But when the technology falls into the wrong hands, no one is safe. Politicians are cut down in broad daylight. The machines descend on a lecture hall and spot activists, who are swiftly dispatched with an explosive to the head.

According to UC Berkeley AI expert Stuart Russell, “Slaughterbots” looks like science fiction. But it’s not. “It shows the results of integrating and miniaturizing technologies that we already have.” It is “simply an integration of existing capabilities… In fact, it is easier to achieve than self-driving cars, which require far higher standards of performance.” Recently shown at the United Nations’ Convention on Conventional Weapons, “Slaughterbots” comes on the heels of an open letter signed by 116 robotics and AI scientists (including Tesla’s Elon Musk), urging the UN to ban the development and use of killer robots. It reads:

Lethal autonomous weapons threaten to become the third revolution in warfare. Once developed, they will permit armed conflict to be fought at a scale greater than ever, and at timescales faster than humans can comprehend. These can be weapons of terror, weapons that despots and terrorists use against innocent populations, and weapons hacked to behave in undesirable ways. We do not have long to act. Once this Pandora’s box is opened, it will be hard to close.

If we already have military drones taking out enemies across the world (in places like Yemen, Somalia, Iraq, Syria, Libya and Afghanistan), the mental leap to deploying Slaughterbots doesn’t seem too great. Do you trust our leaders to make finer distinctions and keep a lid on Pandora’s Box? Or could you see them tearing Pandora’s Box open like a gift on Christmas day? Yeah, me too. The robots of your dystopian future are now here.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Artificial Intelligence: A Free Online Course from MIT

Read More...How American Women “Kickstarted” a Campaign to Give Marie Curie a Gram of Radium, Raising $120,000 in 1921

Image by Bibliothèque nationale de France, via Wikimedia Commons

Marie Curie has a place in history because of her research on radioactivity, of course, but a look into her biography reveals another area she had a part in pioneering: crowdfunding. It happened in 1921, 23 years after she discovered radium and a decade after she won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry (her second Nobel, the first being the Physics prize, shared with her husband Pierre and physicist Henri Becquerel in 1903). The previous year, writes Ann M. Lewicki in the journal Radiology, an American reporter by the name of Marie Meloney had landed a rare interview with Curie, during which the famed physicist-chemist admitted her greatest desire: “some additional radium so that she could continue her laboratory research.”

It seems that “she who had discovered radium, who had freely shared all information about the extraction process, and who had given radium away so that cancer patients could be treated, found herself without the financial means to acquire the expensive substance.” Radium no longer exists in its pure form now, and even in 1921 it was, to quote Back to the Future’s Doc Brown on plutonium, a little hard to come by: it cost $100,000 per gram back then, which Smithsonian.com’s Kat Eschner estimates at “about $1.3 million today.”

The solution arrived in the form of the Marie Curie Radium Fund, launched by Meloney and contributed to by numerous female academics, who raised more than half the full sum in less than a year. And so in 1921, as the National Institute of Standards and Technology tells it, “Marie Curie made her first visit to the United States accompanied by her two daughters Irène and Eve.” They visited, among other places, the Radium Refining Plant in Pittsburgh and the White House, where she received her gram of radium from President Warren Harding. “The hazardous source itself was not brought to the ceremony,” the NIST hastens to add. “Instead, she was presented with a golden key to the coffer and a certificate.”

The real stuff went back on the ship to Paris with her. As for that extra $56,413.54 proto-crowdfunded by the Marie Curie Radium Fund, it eventually went on to support the Marie Curie Fellowship, first awarded in 1963 to support a French or American woman studying chemistry, physics, or radiology. Given the costs of innovative research in those fields today, Curie’s intellectual descendants might have a hard time funding their work on, say, Kickstarter, but they have only to remember what happened when she ran out of radium to remind themselves of the untapped support potentially all around them.

Related Content:

An Animated Introduction to the Life & Work of Marie Curie, the First Female Nobel Laureate

Marie Curie Invented Mobile X‑Ray Units to Help Save Wounded Soldiers in World War I

Marie Curie’s Research Papers Are Still Radioactive 100+ Years Later

New Archive Puts 1000s of Einstein’s Papers Online, Including This Great Letter to Marie Curie

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Google Street View Lets You Walk in Jane Goodall’s Footsteps and Visit the Chimpanzees of Tanzania

As mentioned here last month, Dr. Jane Goodall is now teaching her first online course through Masterclass. In 29 video lessons, her course will teach you about the three pillars of her lifelong work: environmental conservation, animal intelligence, and activism. But that’s not the only way you can digitally engage with Jane Goodall’s world. Over on Google Maps, you can take a visual journey through Gombe National Park in Tanzania, where Goodall conducted her historic chimpanzee research, starting back in July, 1960. As Google writes: this visual initiative lets you experience “what it’s like to be Jane for a day.” You can “peek into her house, take a dip in Lake Tanganyika, spot the chimp named Google and try to keep up with Glitter and Gossamer.” Completed in partnership with Tanzania’s National Parks and the Jane Goodall Institute, this project contributes to an effort to use satellite imagery and mapping to protect 85 percent of the remaining chimpanzees in Africa. To get the most out of Street View Gombe, visit the accompanying website Jane Goodall’s Roots and Shoots.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Animated: The Inspirational Story of Jane Goodall, and Why She Believes in Bigfoot

Google Lets You Take a 360-Degree Panoramic Tour of Street Art in Cities Across the World

Read More...Watch At the Museum, MoMA’s 8‑Part Documentary on What it Takes to Run a World-Class Museum

If you’ve ever visited the Museum of Modern Art — and probably even if you haven’t — you’ll have a sense that the place doesn’t exactly run itself. As much or even more so than other museums, MoMA keeps the behind-the-scenes operations behind the scenes, presenting visitors with coherent art experiences that seem to have materialized whole. But that very purity of presentation itself stokes our curiosity: No, really, how do they do it? Now, MoMA has offered us a chance to see for ourselves through a new series of short documentaries called At the Museum, a look at and a listen to the nuts and bolts of one of America’s mostly highly regarded art institutions.

The series, which will run to eight episodes total, has released four thus far. In “Shipping & Receiving,” some of the museum’s staff prepare 200 works of art in its collection to ship to Paris for a special exhibition at the Louis Vuitton Foundation while others get new shows installed at MoMA itself.

In “The Making of Max Ernst,” a couple of curators design a show of work by that surrealist painter-sculptor-poet. In “Pressing Matters,” the opening of both the Ernst exhibition, “Beyond Painting,” and “Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait” fast approach, but several important decisions remain to be made as well as works to be installed. In “Art Speaks,” MoMA staff and visitors take a step back and contemplate the purpose of modern art itself.

At the Museum could have assumed a highly traditional form, stopping methodically to witness the daily labors of everyone from MoMA’s directors to curators to installers to security guards as narration earnestly explains to us their place in the art ecosystem. From the very first episode, however, the series takes a different and much more compelling tack, providing an uncommented-upon series of fly-on-the-wall views of MoMA people at work, eavesdropping on their conversations, and occasionally weaving in their reflections spoken directly to the filmmakers. But just as the experience of MoMA changes with each new exhibition, so does the form of At the Museum with each new episode, one of which will continue appearing every Friday until December 15th. Watch them all (here), and you’ll never look at MoMA, or indeed any other museum, in quite the same way.

At the Museum will be added to our collection of Free Documentaries, a subset of our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More

Related Content:

Browse Every Art Exhibition Held at MoMA Since 1929 with the New “MoMA Exhibition Spelunker”

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Puts Online 75,000 Works of Modern Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Puts 400,000 High-Res Images Online & Makes Them Free to Use

Kids Record Audio Tours of NY’s Museum of Modern Art (with Some Silly Results)

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Launches Free Course on Looking at Photographs as Art

Free: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim Offer 474 Free Art Books Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...