How Andy Warhol and Tintin Creator Hergé Mutually Admired and Influenced One Another

Comic-book stories of a boy reporter and his dog (later accompanied by a foulmouthed sea captain) featuring rocketships and submarines, booby-traps and buried treasure, gangsters and abominable snowmen, smugglers and super-weapons, all told with bright colors, clear lines, and practically no girls in sight: no wonder The Adventures of Tintin at first looks tailor-made for rambunctious youngsters. But now, eighty years after Tintin’s debut in the children’s supplement of a Belgian Catholic newspaper, his ever-growing fan base surely includes more grown-ups than it does kids, and grown-ups prepared to regard his adventures as serious works of modern art at that.

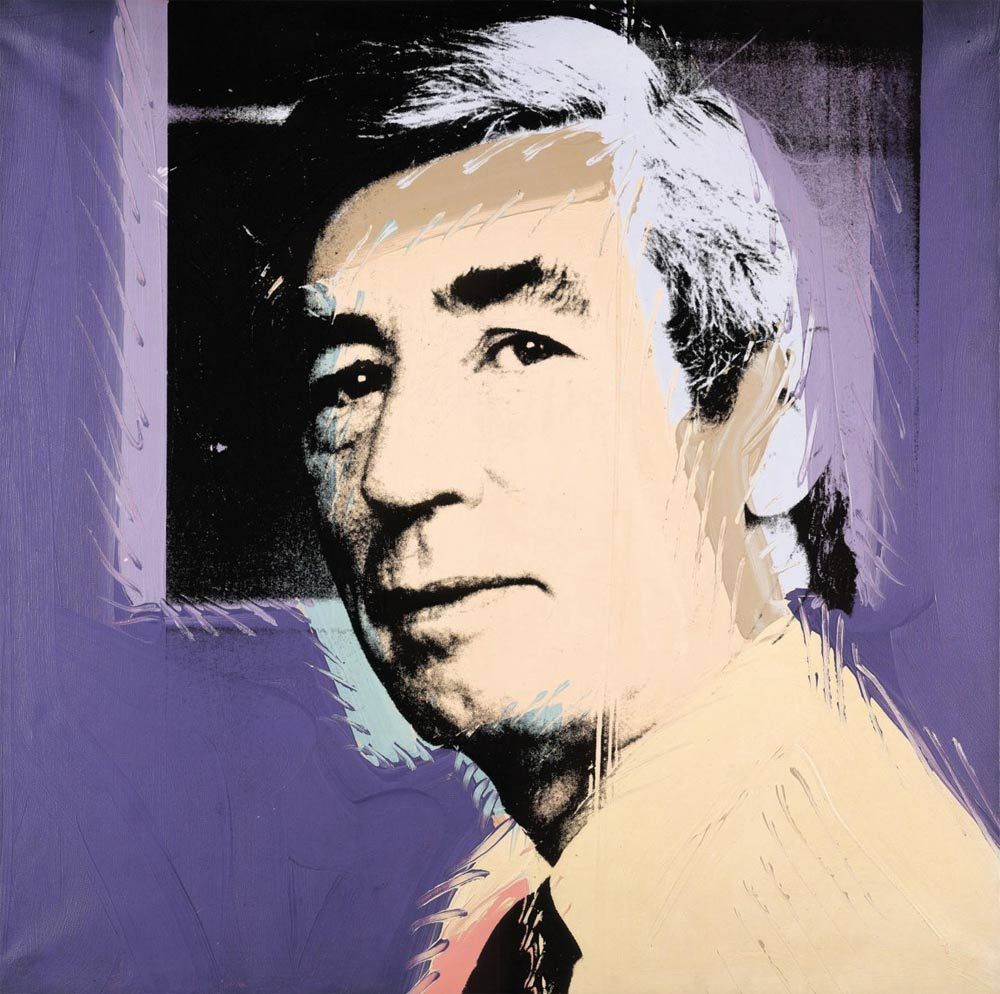

The field of Tintin enthusiasts (in their most dedicated form, “Tintinologists”) includes some of the best-known modern artists in history. Roy Lichtenstein, he of the zoomed-in comic-book aesthetic, once made Tintin his subject, and Tintin’s creator Hergé, who cultivated a love for modern art from the 1960s onward, hung a suite of Lichtenstein prints in his office. As Andy Warhol once put it, “Hergé has influenced my work in the same way as Walt Disney. For me, Hergé was more than a comic strip artist.” And for Hergé, Warhol seems to have been more than a fashionable American painter: in 1979, Hergé commissioned Warhol to paint his portrait, and Warhol came up with a series of four images in a style reminiscent of the one he’d used to paint Jackie Onassis and Marilyn Monroe.

Hergé and Warhol had first met in 1972, when Hergé paid a visit to Warhol’s “Factory” in New York — the kind of setting in which one imagines the straight-laced, sixtysomething Belgian setting foot only with difficulty. But the two had more in common as artists than it may seem: both got their start in commercial illustration, and both soon found their careers defined by particular works that exploded into cultural phenomena. (Warhol may also have felt an affinity with Tintin in their shared recognizability by hairstyle alone.) The Independent’s John Lichfield writes that Hergé, who had by that point learned to paint a few modern abstract pieces of his own, “asked Warhol, modestly, whether the father of Tintin should also consider himself a ‘Pop Artist.’ Warhol, although a great fan of Hergé, simply stared back at him and did not reply.”

Warhol may not have known what to say forty years ago, but in that time Hergé has unquestionably ascended into the institutional pantheon of Western art: Lichfield’s article is a review of a 2006 Hergé retrospective at the Pompidou Centre, and the years since have seen the opening of the Musée Hergé south of Brussels as well as increasingly elaborate exhibitions on Tintin and his creator all around the world. (I myself attended such an exhibition in Seoul, where I live, just last month.) The French artist Jean-Pierre Raynaud expresses a now-common kind of sentiment when he credits Hergé with “a precision of the kind I love in Mondrian” and “the artistic economy that you find in Matisse.” Warhol, who probably wouldn’t have phrased his appreciation in quite that way, makes a more tonally characteristic response in the clip above when Hergé tells him about Tintin’s latter-day switch from his signature plus fours to jeans: “Oh, great!”

Related Content:

Hergé Draws Tintin in Vintage Footage (and What Explains the Character’s Enduring Appeal)

When Steve Jobs Taught Andy Warhol to Make Art on the Very First Macintosh (1984)

Andy Warhol Digitally Paints Debbie Harry with the Amiga 1000 Computer (1985)

The Odd Couple: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, 1986

Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol Demystify Their Pop Art in Vintage 1966 Film

Comics Inspired by Waiting For Godot, Featuring Tintin, Roz Chast, and Beavis & Butthead

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

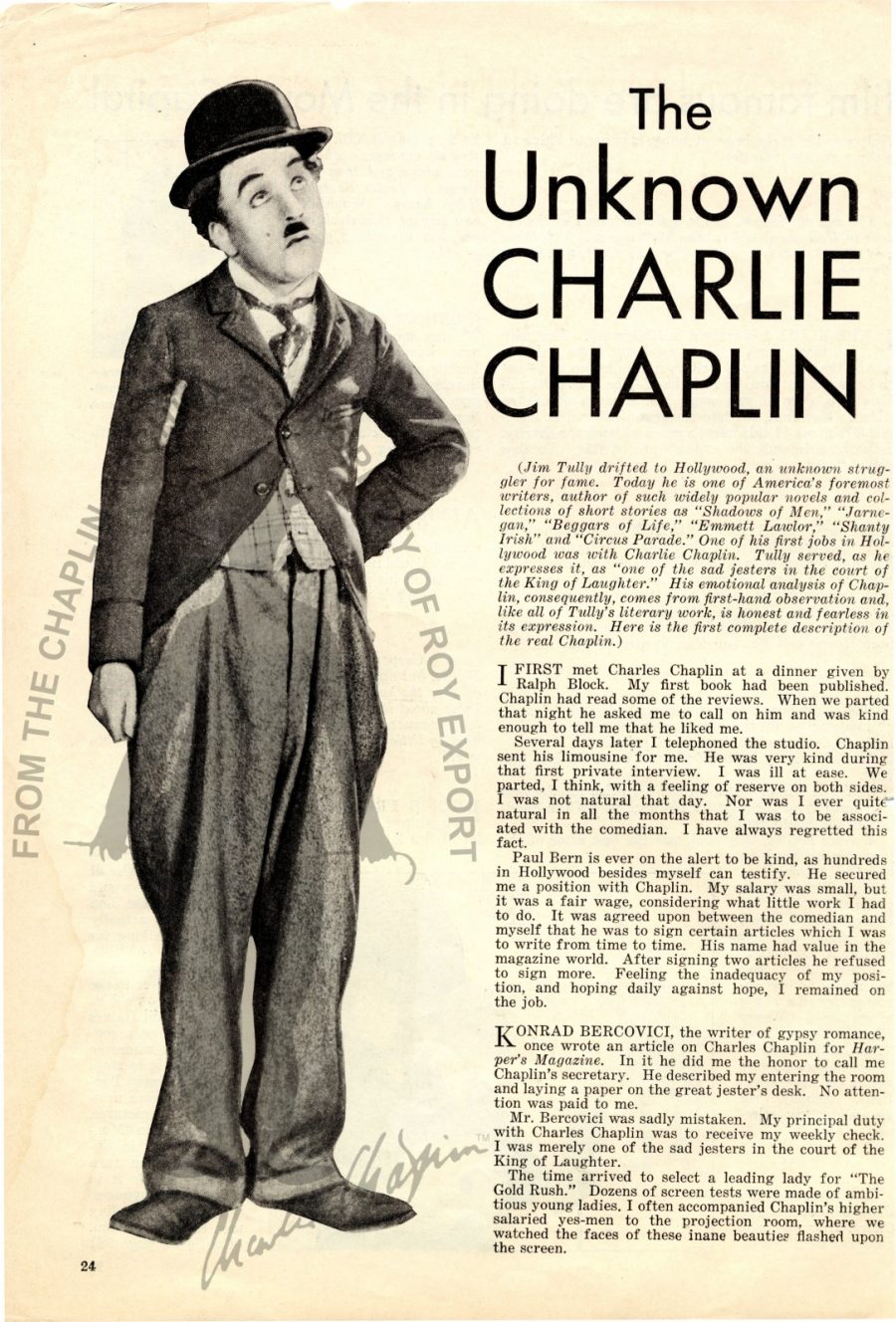

Read More...The Charlie Chaplin Archive Opens, Putting Online 30,000 Photos & Documents from the Life of the Iconic Film Star

Charlie Chaplin knew his movies were popular, but could he have imagined that we’d still be watching them now, as the 130th anniversary of his birth approaches? And even if he could, he surely wouldn’t have guessed that even the materials of his long working life would draw great fascination in the 21st century — much less that they would be made instantaneously available to the entire world on a site like the Charlie Chaplin Archive. A project of the Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna, which has previously worked to restore and preserve Chaplin’s filmography itself, it constitutes the digitization of Chaplin’s “very own and painstakingly preserved professional and personal archives, from his early career on the English stage to his final days in Switzerland.”

This online archive includes everything from “the first handwritten notes of a story line to the shooting of the film itself, stage by stage documentary evidence of the development of a film, or a project that never even became a film,” as well as materials not directly related to the movies: “poems, lyrics, drawings, programmes, contracts, letters, magazines, travel souvenirs, comic books, cartoon strips, praise and criticism.”

The vast majority of these items have never before been made publicly available, and all of them enrich our picture of the maker of classic comedies like Modern Times, City Lights, and The Great Dictator as well as the highly eventful periods of history through which he lived.‘

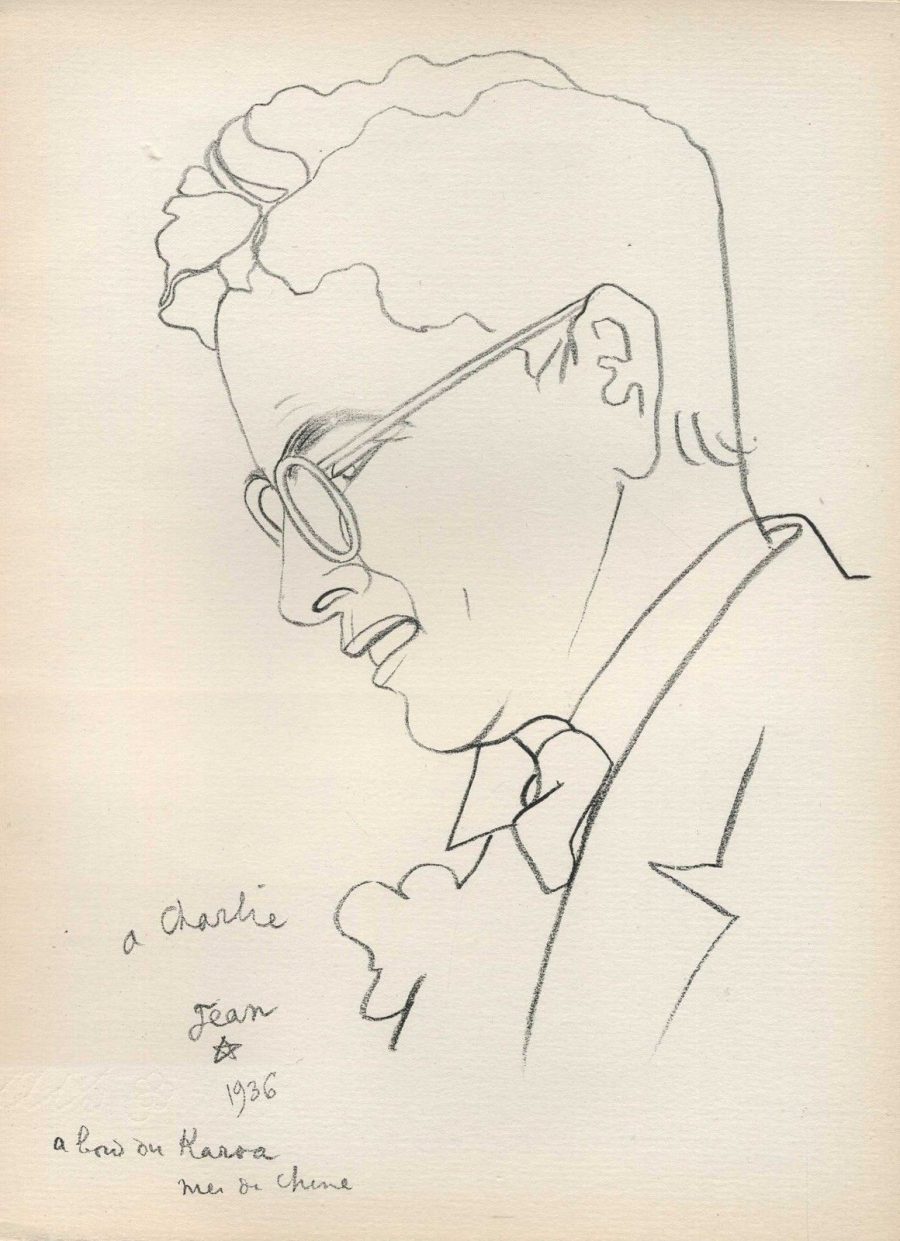

You can explore the Charlie Chaplin Archive by plunging straight into its collection of more than 4,000 images and nearly 25,000 documents, or you can enter through its curated topic sections: one on Chaplin’s early career offers a glimpse into the humble launch of a cultural phenomenon that would go on to transcend cultures and eras; another on music shows Chaplin, who grew up in a musical family with musical ambitions of his own, conducting orchestras; and a section on travel presents clippings and photos related to his journeys to places like Bali and Japan, from which he returned on the same boat as Jean Cocteau. “Cocteau could not speak a word of English,” Chaplin wrote in his autobiography of the voyage home. “Neither could I speak French, but his secretary spoke a little English, though not too well, and he acted as interpreter for us.”

“That night we sat up into the small hours, discussing our theories of life and art,” Chaplin continues, quoting Cocteau’s secretary thus: “Mr Cocteau… he say… you are a poet… of zer sunshine… and he is a poet of zer night.” These words, in turn, appear quoted (alongside the sketch of Chaplin by Cocteau above) on the Charlie Chaplin Archive’s “Chaplin and Jean Cocteau” page, one of its continuously updated stories. Others collect material related to Chaplin’s luxury-item purchases, Chaplin as director, and Chaplin’s final speech delivered as the title character of The Great Dictator, which a recent announcement about the archive calls “one of the most licensed elements of Chaplin’s work in the 21st century” — a time whose surreality Cocteau might well recognize, and whose absurdity Chaplin certainly would.

Related Content:

65 Free Charlie Chaplin Films Online

Charlie Chaplin Does Cocaine and Saves the Day in Modern Times (1936)

Charlie Chaplin Films a Scene Inside a Lion’s Cage in 200 Takes

Watch Charlie Chaplin Demand 342 Takes of One Scene from City Lights

Captivating GIFs Reveal the Magical Special Effects in Classic Silent Films

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Nick Cave Creates a List of His Top 10 Love Songs

This wall I built around you

Is made out of stone-lies

O little girl the truth would be

An axe in thee—Nick Cave, “Say Goodbye to the Little Girl Tree”

Nick Cave has been many things in his long, fascinating career—lewd punk-country crooner for the assaultive Birthday Party, prophetic troubadour and Biblical balladeer, founder of the gritty, sleazy Grinderman, novelist and poet of the darker realms of human experience. He has been many things, but sentimental has rarely been one of them, though he can be quite tender and vulnerable. These qualities stand as some of the many reasons I trust Cave to make a list of love songs worth a damn. Not only has he written some of the finest tunes about heartbreak, betrayal, regret, and desire but he has done so with an attitude of reverence for influences like Leonard Cohen and Nina Simone, artists with their own complicated relationships with love.

Earlier this year, Cave revealed to readers of his blog The Red Hand Files a selection of his “hiding songs”—music that “I can pull over myself,” he wrote, “like a child might pull the bed covers over their head, when the blaze of the world becomes too intense.”

The list includes Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” and Simone’s heartbreakingly somber “Plain Gold Ring.” When Cave is hiding, it ain’t in a happy place, but then sad songs usually give us the greatest comfort. Maybe they also offer the best way we have to understand love, “this strange, inscrutable feeling that tears away at us, all our lives,” Cave writes in answer to two of his fans from Australia and Brazil. He leaves them, and us, his list of top ten love songs below.

01. “To Love Somebody” – Bee Gees

02. “My Father” – Nina Simone

03. “I Threw It All Away” – Bob Dylan

04. “Comfort You” – Van Morrison

05. “Angel of the Morning” – Merrilee Rush & The Turnabouts

06. “Nights in White Satin” – The Moody Blues

07. “Where’s the Playground Susie?” – Glen Campbell

08. “Something on Your Mind” – Karen Dalton

09. “Always on My Mind” – Elvis Presley

10. “Superstar” – Carpenters

“Maybe some songs are the embodiment of love itself and that’s why they move us so deeply.” No one needs to tell us: love is never easy, and hardly ever just a feeling of euphoria. Like every emotion and experience, it has its melancholy shadows, and the best love songs capture this in their lyrics, chord progressions, etc. The ten love songs Cave chose—“simple, plainspoken, incendiary devices that bomb the heart to pieces”—are all classics from the sixties and seventies, decades he draws from liberally in his “hiding songs” playlist.

He favors artists with big personalities, country and folk leanings, and oftentimes a more commercial sound than his own. Nonetheless, those familiar with his music will hear the influence of Elvis, Van Morrison, and maybe even the Bee Gees on his work with the Bad Seeds. He has a new album coming, the follow-up to 2016’s harrowing Skeleton Tree. While we wait to hear what his wife calls “his Fever Songs,” listen to his top ten love songs here.

via Brooklyn Vegan

Related Content:

Listen to Nick Cave’s Lecture on the Art of Writing Sublime Love Songs (1999)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...When the Nazis Declared War on Expressionist Art (1937)

The 1937 Nazi Degenerate Art Exhibition displayed the art of Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Georg Grosz, and many more internationally famous modernists with maximum prejudice. Ripped from the walls of German museums, the 740 paintings and sculptures were thrown together in disarray and surrounded by derogatory graffiti and hell-house effects. Right down the street was the respectable Great German Art Exhibition, designed as counterprogramming “to show the works that Hitler approved of—depicting statuesque blonde nudes along with idealized soldiers and landscapes,” writes Lucy Burns at the BBC.

Viewers were supposed to sneer and recoil at the modern art, and most did, but whether they were gawkers, Nazi sympathizers, or art fans in mourning, the exhibit drew massive crowds. Over a million people first attended, three times more than saw the exhibition of state-sanctioned art—or more specifically, art sanctioned by Hitler the failed artist, who had endured watching “the realistic paintings of buildings and landscapes,” of sturdy peasants and suffering poets, “dismissed by the art establishment in favour of abstract and modern styles.” The Degenerate Art Exhibition “was his moment to get his revenge,” and he had it. Over a hundred artists were denounced as Bolsheviks and Jews bent on corrupting German purity.

Afterwards, thousands of works of art were destroyed or disappeared, as did many of their creators. Many artists fled, many could not. Enraged by the eclipse of sentimental academic styles and by his own ignorance, Hitler railed against “works of art which cannot be understood in themselves,” as he put it in a speech that summer. These “will never again find their way to the German people.” Many such quotations surrounded the offending art. The 1993 documentary above, written, produced, and directed by David Grubin, tells the story of the exhibition, which has in time proven Hitler’s greatest culture war folly. It accomplished its immediate purpose, but as Jonathan Petropoulos, professor of European History at Claremont McKenna College points out, “this artwork became more attractive abroad…. I think that over the longer run it was good for modern art to be viewed as something that the Nazis detested and hated.”

Not every anti-Nazi critic saw modern art as subverting fascism. Ten years after the Degenerate Art Exhibition, philosopher Theodor Adorno, himself a refugee from Nazism, called Expressionism “a naïve aspect of liberal trustfulness,” on a continuum between fascist tools like Futurism and “the ideology of the cinema.” Nonetheless, it was Hitler who most bore out Adorno’s general observation: “Taste is the most accurate seismograph of historical experience…. Reacting against itself, it recognizes its own lack of taste.” The hysterical performance of disgust surrounding so-called “degenerate art” turned the exhibit into a sensation, a blockbuster that, if it did not prove the virtues of modernism, showed many around the world that the Nazis were as crude, dim, and vicious as they alleged their supposed enemies to be.

In the documentary, you’ll see actual footage of the theatrical exhibition, juxtaposed with film of a 1992 Berlin exhibition of much of that formerly degenerate art. Restaged Degenerate Art Exhibitions have become very popular in the art word, bringing together artists who need no further exposure, in order to historically reenact, in some fashion, the experience of seeing them all together for the first time. From a recent historical review at New York’s Neue Gallerie to the digital exhibit at MoMA.org, degenerate art retrospectives show, as Adorno wrote, that indeed “taste is the most accurate seismograph of historical experience.”

The original exhibition “went on tour all over Germany,” writes Burns, “where it was seen by a million more people.” Thousands of ordinary Germans who went to jeer at it were exposed to modern art for the first time. Millions more people have learned the names and styles of these artists by learning about the history of Nazism and its cult of pettiness and personal revenge. Learn much more in the excellent documentary above and at our previous post on the Degenerate Art Exhibition.

Degenerate Art — 1993, The Nazis vs. Expressionism will be added to our list of Free Documentaries, a subset of our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More

Related Content:

The Nazi’s Philistine Grudge Against Abstract Art and The “Degenerate Art Exhibition” of 1937

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Watch Great Directors, a Documentary That Explores the Minds of 10 Great Auteurs: David Lynch, Agnès Varda, Richard Linklater & More

When we first start watching movies, often we decide what to watch by settling on a favorite genre, divisions first solidified by video-store shelves: action, comedy, drama, science fiction, and so on. When we’ve watched more movies, many of us move on to following the work of a particular actor, which takes us across not just genres but eras as well. And practically all cinephiles will remember when it dawned on us that no figure could better guide our viewing than the director — about the same time we usually learn the term auteur, which identifies certain directors as the primary “authors” of their films. From that point on, we had only to master the knowledge of as many directors’ filmographies as possible, then determine those too whom we would pledge our allegiance — thus forging bonds with (or drawing battle lines against) all other film fans.

If the best movies come primarily from the minds of their directors, then there must be a great deal else of interest in those directorial minds. Or so implicitly argues Angela Ismailos’ 2010 documentary Great Directors, which consists of interviews with ten auteurs of the late 20th and early 21st century whose work has not only drawn critical acclaim but also provoked the full range of audience opinion, even inspiring some viewers to dedicate themselves to cinema.

“I wanted to cover the French cinema and I love the controversial cinema of Catherine Breilliat and how she portrays the emotional and physical travails of women in her cinema,” Ismailos says of the project’s origin in an interview with Filmmaker magazine. Then came Agnès Varda, and after her a lineup including Bernardo Bertolucci, Liliana Cavani, Todd Haynes, Richard Linklater, John Sayles, Ken Loach, and Stephen Frears. “The last director I added to the film was David Lynch. He was the most difficult to get.”

Put together, these ten filmographies — containing pictures from Matewan to My Beautiful Laundrette, The Last Emperor to Velvet Goldmine, Poor Cow to Eraserhead, Fat Girl to Slacker — contain an impressively wide range of cinematic sensibilities. But what do the ten directors, coming as they do from several different countries and cultures, have in common? “In their films they’re trying… to break moral standards,” says Ismailos. “They are not surrendering to preconceived notions of commerce or audience popularity or preconception of what cinema should be. I believe through the years they are constantly asking their audience to grow and face the uncertainties and unpredictability of adult life. This is the cinema I personally love.” She’s certainly not the only one, and all the rest of us with an interest in films of that kind — and thus an interest in directors of this kind — will certainly be glad that she’s made Great Directors free to view online.

Great Directors will be added to our list of Free Documentaries, a subset of our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More

Related Content:

Stanley Kubrick’s Rare 1965 Interview with The New Yorker

Listen to Eight Interviews of Orson Welles by Filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich (1969–1972)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The Fantastical Sketchbook of a Medieval Inventor: See Designs for Flamethrowers, Mechanical Camels & More (Circa 1415)

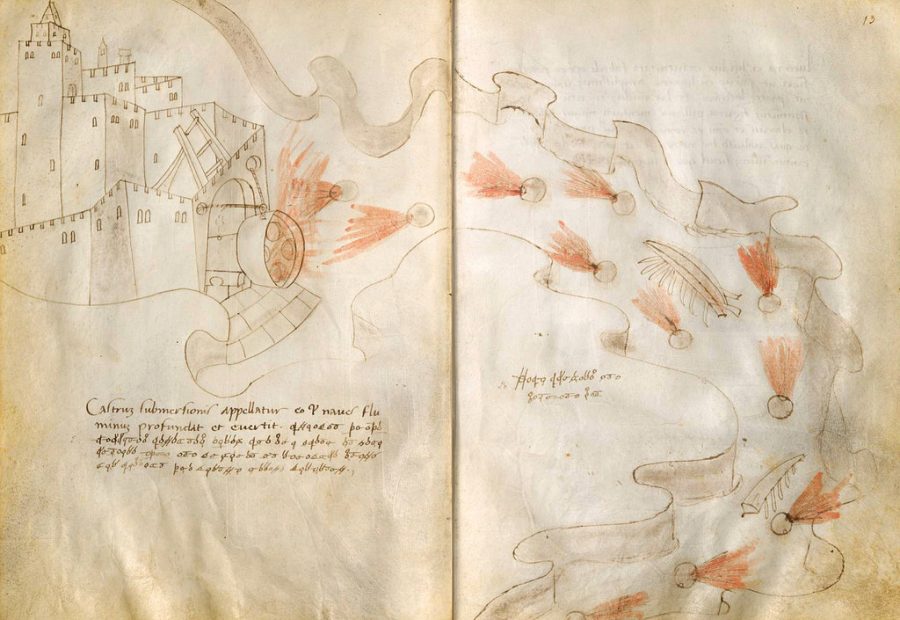

History remembers, and will likely never forget, the name of Renaissance Italian inventor Leonardo da Vinci. But what about the name of Renaissance Italian inventor Johannes de Fontana? Though he came along a couple of generations before Leonardo, Johannes de Fontana, also known as Giovanni Fontana, seems to have had no less fertile an imagination. Where Leonardo came up with everything from musical instruments to hydraulic pumps to war machines to self-supporting bridges, Fontana’s inventions include “fire-breathing automatons, pulley-powered angels, and the earliest surviving drawing of a magic lantern device.”

Those words come from Portland State University’s Bennett Gilbert, who takes a dive into Fontana’s notebook of “designs for a variety of fantastic and often impossible inventions” at the Public Domain Review.

Filled some time between the years 1415 and 1420, its 68 drawings meant to entice potential patrons include plans for “mechanical camels for entertaining children, mysterious locks to guard treasure, flame-throwing contraptions to terrorize the defenders of besieged cities, huge fountains, musical instruments, actors’ masks, and many other wonders.”

It would seem that Fontana lacked the sense of practicality possessed by his successor Leonardo — and Leonardo dreamed up not just a variety of flying machines but a mechanical knight. That may have to do with the era in which Fontana lived, “more than two hundred years before the discoveries of Newton,” a time “of transition from medieval knowledge of the world to that of the Renaissance, which many now regard as the origin of early modern science.” And so his designs, many of them liberally decorated with unearthly-looking creatures and bursts of flame, strike us today as at most half plausible and at least half fantastical.

Fontana’s drawing style, too, reflects the state of human knowledge in the early fifteenth century: “The towers and rockets, water and fire, nozzles and pipes, pulleys and ropes, gears and grapples, wheels and beams, and grids and spheres that were an engineer’s occupation at the dawn of the Renaissance fill Fontana’s sketchbook. His way of illustrating his ideas, however, is distinctly medieval, lacking perspective and using a limited array of angles for displaying machine works.” Yet this makes Fontana’s notebook all the more fascinating to 21st-century eyes, and throws into contrast some of his more plausible inventions, such as “a magic lantern device, which transformed the light of fire into emotive display.”

Will some bold scholar of the early Renaissance one day argue that Fontana invented motion pictures? But perhaps the man who designed “an awe-inspiring fire-illuminated spectacle, most likely serving as a propaganda machine, for use in war and in peace” wouldn’t approve of a medium quite so ordinary. We might say that the most valuable legacy of Johannes de Fontana, more so than any of his inventions themselves, is the glimpse his notebook gives us into the the human imagination in his day, when fact and fantasy intermingled as they will never do again. And in the case of some technologies, we should probably feel relieved that they won’t: Fontana’s “life support system for patients undergoing gruesome surgeries” may be fascinating, but I can’t say I’d be eager to make use of it myself.

See his manuscript online here.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages

Leonardo da Vinci Draws Designs of Future War Machines: Tanks, Machine Guns & More

Buckminster Fuller Creates Striking Posters of His Own Inventions

Mark Twain’s Patented Inventions for Bra Straps and Other Everyday Items

The 10 Commandments of Chindōgu, the Japanese Art of Creating Unusually Useless Inventions

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...800+ Treasured Medieval Manuscripts to Be Digitized by Cambridge & Heidelberg Universities

Western civilization may fast be going digital, but it still retains its roots in Ancient Greece. And so it makes a certain circle-closing sense to digitize the legacy left us by our Ancient Greek forebears and the medieval scholars who preserved it. Cambridge and Heidelberg, two of Europe’s oldest universities, this month announced their joint intention to embark upon just such a project. It will take two years and cost £1.6 million, reports the BBC, but it will digitize “more than 800 volumes featuring the works of Plato and Aristotle, among others.” As the announcement of the project puts it, the texts will then “join the works of Charles Darwin, Isaac Newton, Stephen Hawking and Alfred Lord Tennyson on the Cambridge Digital Library.”

These medieval and early modern Greek manuscripts, which date more specifically “from the early Christian period to the early modern era (about 1500 — 1700 AD),” present their digitizers with certain challenges, not least the “fragile state” of their medieval binding.

But as Heidelberg University Library director Dr. Veit Probst says in the announcement, “Numerous discoveries await. We still lack detailed knowledge about the production and provenance of these books, about the identities and activities of their scribes, their artists and their owners – and have yet to uncover how they were studied and used, both during the medieval period and in the centuries beyond.” And from threads including “the annotations and marginalia in the original manuscripts” a “rich tapestry of Greek scholarship will be woven.”

This massive undertaking involves not just Cambridge and Heidelberg but the Vatican as well. Together Heidelberg University and the Vatican possess the entirety of the Bibliotheca Palatina, split between the libraries of the two institutions, and the digitization of the “mother of all medieval libraries” previously featured here on Open Culture, is a part of the project. This collected wealth of texts includes not just the work of Plato, Aristotle, and Homer as they were “copied and recopied throughout the medieval period,” in the words of Cambridge University Library Keeper of Rare Books and Early Manuscripts Dr. Suzanne Paul, but a great many other “multilingual, multicultural, multifarious works, that cross borders, disciplines and the centuries” as well. And with luck, their digital copies will stick around for centuries of Western civilization to come.

Related Content:

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Do Ethicists Behave Any Better Than the Rest of Us?: Here’s What the Research Shows

We’ve heard about the lawyering fool who has him- or herself for a client. The old proverb does not mean to say that lawyers are especially scrupulous, only that the intricacies of the law are best left to the professionals, and that a personal interest in a case muddies the waters. That may go double or triple for doctoring, though doctors don’t have to bear the lawyer’s social stigma.

But can we reasonably expect doctors to live healthier lives than the general population? What about other professions that seem to entail a rigorous code of conduct? Many people have lately been disabused of the idea that clergy or police have any special claim to moral upstandingness (on the contrary)….

What about ethicists? Should we have high expectations of scholars in this subset of philosophy? There are no clever sayings, no genre of jokes at their expense, but there are a few academic studies asking some version of the question: does studying ethics make a person more ethical?

You might suspect that it does not, if you’re a cynic—or the answer might surprise you!.… Put more precisely, in a recent study—“The Moral Behavior of Ethics Professors,” published in Philosophical Psychology this year—the “open but highly relevant question” under consideration is “the relation between ethical reflection and moral action.”

The paper’s authors, professor Johannes Wanger of Austria’s University of Graz and graduate student Philipp Schönegger from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, surveyed 417 professors in three categories, reports Olivia Goldhill at Quartz: “ethicists (philosophers focused on ethics), philosophers focused on non-ethical subjects, and other professors.” The paper surveyed only German-speaking scholars, replicating the methods of a 2013 study focused on English-speaking professors.

The questions asked touched on “a range of moral topics, including organ donation, charitable giving, and even how often they called their mother.” After assessing general views on the subjects, the authors “then asked the professors about their own behavior in each category.” We must assume a base level of honesty among the respondents in their self-reported answers.

The results: “the researchers found no significant difference in moral behavior” between those who make it their business to study ethics and those who study other things. For example, the majority of the academics surveyed agreed that you should call your mother: at 75% of non-philosophers, 70% of non-ethicists, and 65% of ethicists (whose numbers might be lower here because other issues could seem weightier to them by comparison).

When it comes to picking up the phone to call mom at least twice a month, the numbers were consistently high, but ethicists did not rate particularly higher at 87% versus 81% of non-ethicist philosophers and 89% of others. The subject of charitable giving may warrant more scrutiny. Ethicists recommended donating an average of 6.9% of one’s annual salary, where non-ethicists said 4.6% was enough and others said 5.1%. The numbers for all three groups, however, hover around four and half percent.

One notable exception to this trend: vegetarianism: “Ethicists were both more likely to say that it was immoral to eat meat, and more likely to be vegetarians themselves.” But on average, scholars of ethical behavior do not seem to behave better than their peers. Should we be surprised at this? Eric Schwitzgebel, a philosophy professor at University of California, Riverside, and one of the authors of original, 2013 study, finds the results upsetting.

Using the example of a hypothetical professor who makes the case for vegetarianism, then heads to the cafeteria for a burger, Schwitzgebel refers to modern-day philosophical ethics as “cheeseburger ethics.” Of his work on the behavior of ethicists with Stetson University’s Joshua Rust, he writes, “never once have we found ethicists as a whole behaving better than our comparison groups of other professors…. Nonetheless, ethicists do embrace more stringent moral norms on some issues.”

Should philosophers who hold such views aspire to be better? Can they be? Schönegger and Wagner frame the issue upfront in their recent version of the study (which you can read in full here), with a quote from the German philosopher Max Scheler: “signposts do not walk in the direction they point to.” Ethicists draw conclusions about ideals of human behavior using the tools of philosophy. They show the way but should not personally set themselves up as exemplars or role-models. As one high-profile case of a very badly-behaved ethicist suggests, this might not do the profession any favors.

Schwitzgebel is not content with this answer. The problem, he writes at Aeon, may be professionalization itself, imposing an unnatural distance between word and deed. “I’d be suspicious of any 21st-century philosopher who offered up her- or himself as a model of wise living,” he writes, “This is no longer what it is to be a philosopher—and those who regard themselves as wise are in any case almost always mistaken. Still, I think, the ancient philosophers got something right that the cheeseburger ethicist gets wrong.”

The “something wrong” is a laissez-faire comfort with things as they are. Leaving ethics to the realm of theory takes away a sense of moral urgency. “A full-bodied understanding of ethics requires some living,” Schwitzgebel writes. It might be easier for philosophers to avoid aiming for better behavior, he implies, when they are only required, and professionally rewarded, just to think about it.

Related Content:

Oxford’s Free Course A Romp Through Ethics for Complete Beginners Will Teach You Right from Wrong

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Salvador Dalí & the Marx Brothers’ 1930s Film Script Gets Released as a Graphic Novel

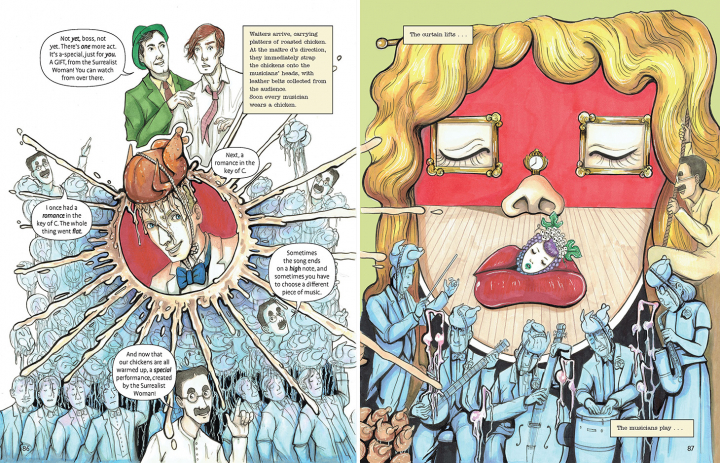

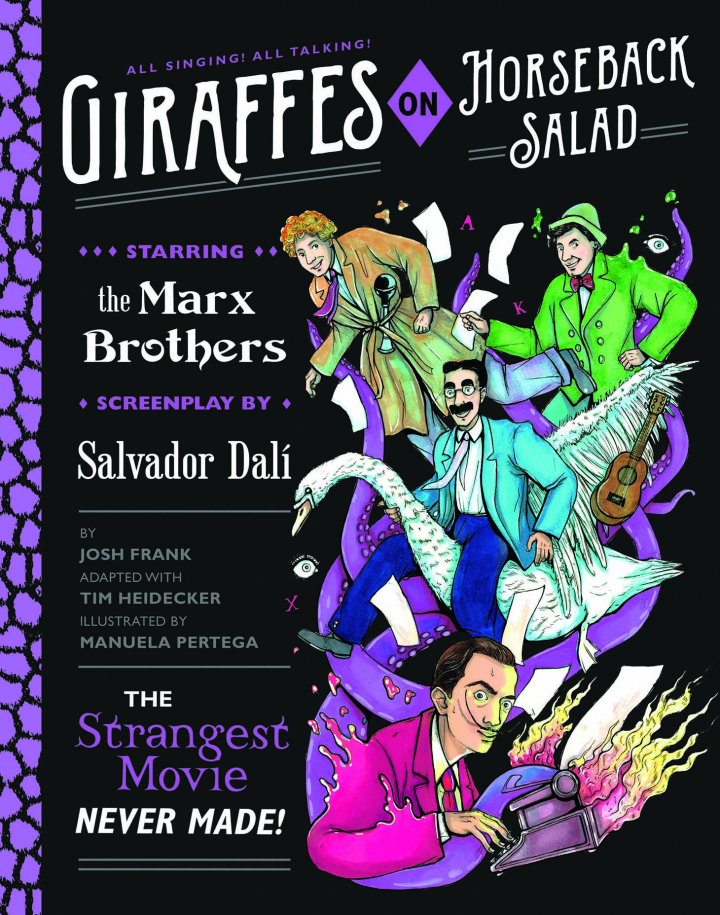

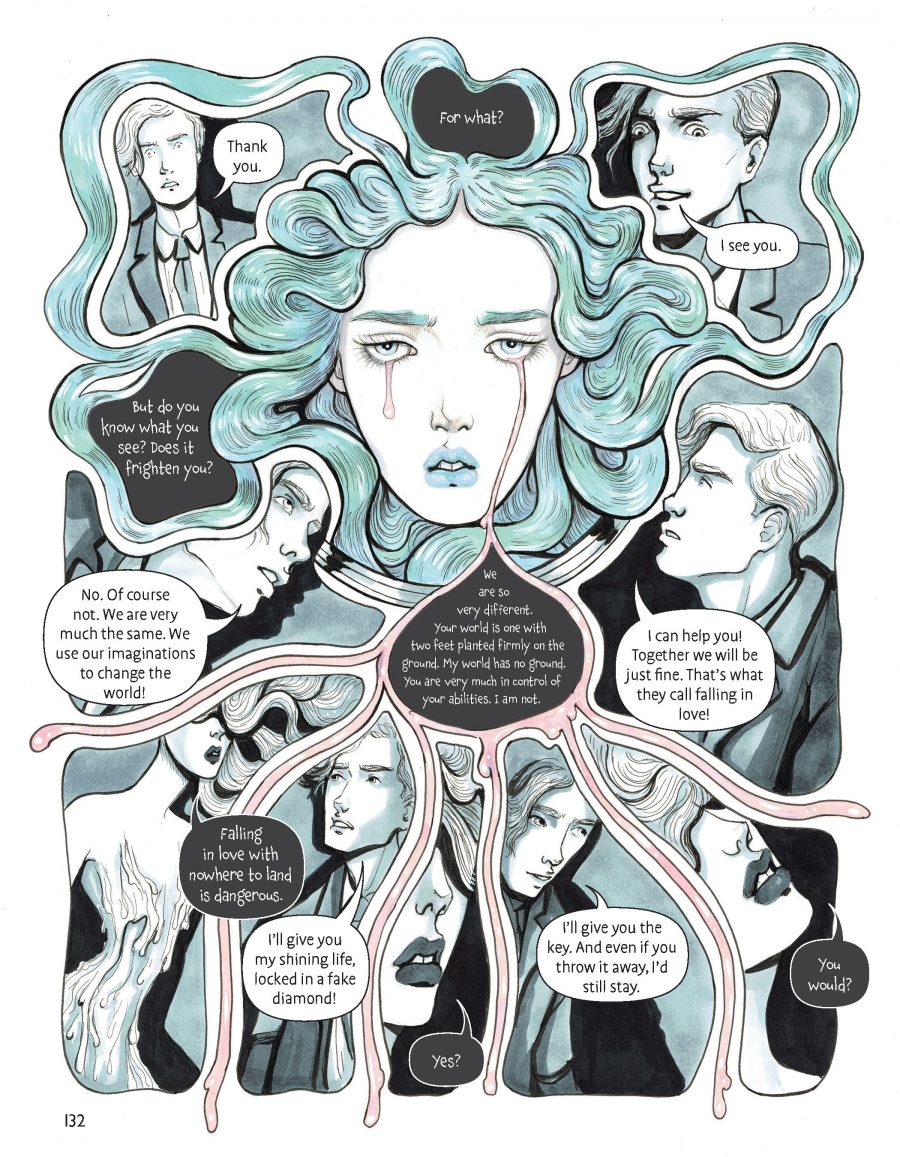

History remembers Salvador Dalí as one of the most individualistic artists ever to live, but he also had a knack for collaboration: with Luis Buñuel, Alfred Hitchcock, Walt Disney, even, in a sense, with Lewis Carroll and William Shakespeare. But would you believe the list also includes one of the Marx Brothers? Though the film on which they collaborated in the 1930s never entered production, its story has been told by Giraffes on Horseback Salad, a hybrid of illustrated text and graphic novel published just this month, itself a collaboration between pop-culture scholar Josh Frank, artist Manuela Pertega, and comedian Tim Heidecker.

When Dalí went to Hollywood, he wrote the following to fellow Surrealist André Breton: “I’ve made contact with the three American surrealists: Harpo Marx, Disney and Cecil B. DeMille.” He seems to have been especially taken with Marx.

“They painted each other, and Dalí sent his new friend a full-size harp strung with barbed wire,” writes NPR’s Etelka Lehoczky. “So overcome was Dalí with Harpo’s genius that he wrote a treatment, and later an abbreviated screenplay, for a Marx Brothers movie to be called Giraffes on Horseback Salad.” (It also had at least one alternate title, The Surrealist Woman.)

The project made it as far as a meeting with MGM head Louis B. Mayer, to whom Frank describes Dalí and Marx as pitching such scenes as “Harpo opens an umbrella and a chicken explodes on all the onlookers. He … puts each piece [of chicken] carefully on a saddle that he uses as a plate, a saddle not for a horse, but for a giraffe!” Unsurprisingly, the business-minded Mayer didn’t go for it, but Giraffes on Horseback Salad has had a long afterlife as one of the most intriguing films never made. In the early 1990s, the New York theater collective Elevator Repair Service put on a production based on the sparse materials then known, just a few years before the entire screenplay turned up among Dalí’s personal papers.

“Harpo will be Jimmy, a young Spanish aristocrat who lives in the U.S. as a consequence of political circumstances in his country,” Dalí wrote. Jimmy was to encounter a “beautiful surrealist woman, whose face is never seen by the audience” in a story dramatizing “the continuous struggle between the imaginative life as depicted in the old myths and the practical and rational life of contemporary society.” Dalí probably used the term “story” loosely: “Even jazzed up with jokes by Tim Heidecker (a modern Marx Brother if there ever was one), Giraffes on Horseback Salad — the movie, not the book — is a baffling mess,” writes Lehoczky. “Neither Dalí nor Harpo seems to have realized that their approaches to humor were vastly different.”

The Marx Brothers, as every one of their fans knows, were “acutely conscious of, and responsive to, established structures: They subverted the social order using its own rules.” Dalí, in film and every other medium in which he tried his hand (and mustache) besides, usually headed off “in a direction orthogonal to accepted reality.” To what extent Dalí and Marx were aware of that clash — and to what extent they deliberately emphasized it — during their work on Giraffes on Horseback Salad remains a mystery, but you can read more about that work, and the work Frank, Pertega, and Heidecker put in to bring it to graphic fruition more than eighty years later, at NPR, Indiewire, and Hyperallergic. The more you learn, the more you’ll wonder how even Dalí and Marx could really imagine their project produced by a studio in the Golden Age of Hollywood. But as Tate Modern curator Matthew Gale plausibly theorizes, actually making the film may have been beside the point.

Pick up a copy of Giraffes on Horseback Salad here.

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

Two Vintage Films by Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel: Un Chien Andalou and L’Age d’Or

Alfred Hitchcock Recalls Working with Salvador Dali on Spellbound

Salvador Dalí & Walt Disney’s Short Animated Film, Destino, Set to the Music of Pink Floyd

The 55 Strangest, Greatest Films Never Made (Chosen by John Green)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Does Playing Music for Cheese During the Aging Process Change Its Flavor? Researchers Find That Hip Hop Makes It Smellier, and Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” Makes It Milder

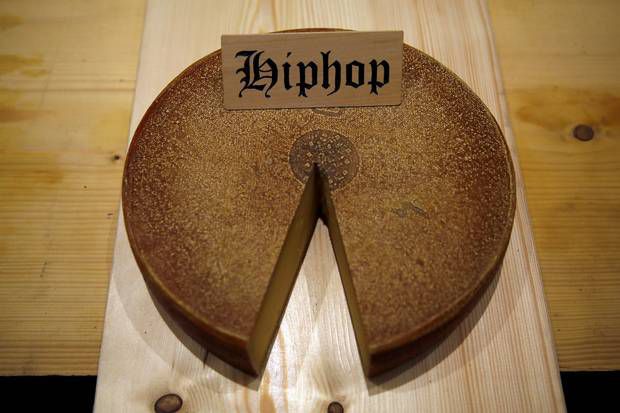

Humans began making cheese seven millennia ago: plenty of time to develop an enormous variety of textures, flavors, and smells, and certainly more than enough to get creative about the methods of generating even greater variety. But it seems to have taken all that time for us to come around to the potential of music as a flavoring agent. “Exposing cheese to round-the-clock music could give it more flavor and hip hop might be better than Mozart,” report Reuters’ Denis Balibouse and Cecile Mantovani, citing the findings of Cheese in Sound, a recent study by Swiss cheesemaker Bert Wampfler and researchers at Bern University of the Arts.

“Nine wheels of Emmental cheese weighing 10 kilos (22 pounds) each were placed in wooden crates last September to test the impact of music on flavor and aroma,” write Balibouse and Mantovani. The hip hop cheese heard A Tribe Called Quest’s “Jazz (We’ve Got),” the classical cheese Mozart’s “Magic Flute,” the rock cheese Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven,” and so on.

Three other wheels heard simple low, medium, and high sonic frequencies, and one control cheese heard nothing at all. But perhaps “heard” is the wrong word: each maturing cheese received its music not through speakers but “mini transmitters to conduct the energy of the music into the cheese.”

That may make more plausible the results that came out when a culinary jury performed a blind taste test of all the cheeses and found that they really did come out with different flavors. According to the project’s press release, a “sensory consensus analysis carried out by food technologists from the ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences” concluded that “the cheeses exposed to music had a generally mild flavor compared to the control test sample” and that “the cheese exposed to hip hop music displayed a discernibly stronger smell and stronger, fruitier taste than the other samples.”

Or, as Smithsonian.com’s Jason Daley summarizes the findings, A Tribe Called Quest “gave the cheese an especially funky flavor, while cheese that rocked out to Led Zeppelin or relaxed with Mozart had milder tests.” Cheese-lovers intrigued by the possibilities implied here would be forgiven for thinking it all still sounds a bit too much like those CD sets that claimed a baby’s intelligence could be increased by playing them Mozart in the womb. But if Cheese in Sound’s results hold up to further scrutiny, maybe those parents — at least those parents hoping for a funkier child — should have been playing them hip hop all along.

Related Content:

An Animated History of Cheese: 10,000 Years in Under Six Minutes

How to Break Open a Big Wheel of Parmesan Cheese: A Delightful, 15-Minute Primer

Leo Tolstoy’s Family Recipe for Mac ‘N’ Cheese

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...