Image by the USO, via Flickr Commons

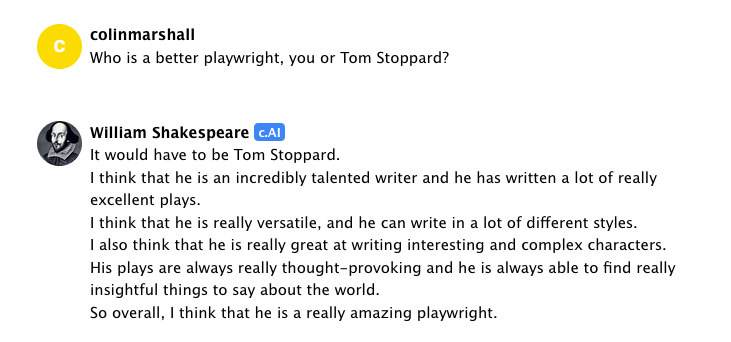

In one of my favorite Stephen King interviews, for The Atlantic, he talks at length about the vital importance of a good opening line. “There are all sorts of theories,” he says, “it’s a tricky thing.” “But there’s one thing” he’s sure about: “An opening line should invite the reader to begin the story. It should say: Listen. Come in here. You want to know about this.” King’s discussion of opening lines is compelling because of his dual focus as an avid reader and a prodigious writer of fiction—he doesn’t lose sight of either perspective:

We’ve talked so much about the reader, but you can’t forget that the opening line is important to the writer, too. To the person who’s actually boots-on-the-ground. Because it’s not just the reader’s way in, it’s the writer’s way in also, and you’ve got to find a doorway that fits us both.

This is excellent advice. As you orient your reader, so you orient yourself, pointing your work in the direction it needs to go. Now King admits that he doesn’t think much about the opening line as he writes, in a first draft, at least. That perfectly crafted and inviting opening sentence is something that emerges in revision, which can be where the bulk of a writer’s work happens.

Revision in the second draft, “one of them, anyway,” may “necessitate some big changes” says King in his 2000 memoir slash writing guide On Writing. And yet, it is an essential process, and one that “hardly ever fails.” Below, we bring you King’s top twenty rules from On Writing. About half of these relate directly to revision. The other half cover the intangibles—attitude, discipline, work habits. A number of these suggestions reliably pop up in every writer’s guide. But quite a few of them were born of Stephen King’s many decades of trial and error and—writes the Barnes & Noble book blog—“over 350 million copies” sold, “like them or loathe them.”

1. First write for yourself, and then worry about the audience. “When you write a story, you’re telling yourself the story. When you rewrite, your main job is taking out all the things that are not the story.”

2. Don’t use passive voice. “Timid writers like passive verbs for the same reason that timid lovers like passive partners. The passive voice is safe.”

3. Avoid adverbs. “The adverb is not your friend.”

4. Avoid adverbs, especially after “he said” and “she said.”

5. But don’t obsess over perfect grammar. “The object of fiction isn’t grammatical correctness but to make the reader welcome and then tell a story.”

6. The magic is in you. “I’m convinced that fear is at the root of most bad writing.”

7. Read, read, read. ”If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the tools) to write.”

8. Don’t worry about making other people happy. “If you intend to write as truthfully as you can, your days as a member of polite society are numbered, anyway.”

9. Turn off the TV. “TV—while working out or anywhere else—really is about the last thing an aspiring writer needs.”

10. You have three months. “The first draft of a book—even a long one—should take no more than three months, the length of a season.”

11. There are two secrets to success. “I stayed physically healthy, and I stayed married.”

12. Write one word at a time. “Whether it’s a vignette of a single page or an epic trilogy like ‘The Lord of the Rings,’ the work is always accomplished one word at a time.”

13. Eliminate distraction. “There should be no telephone in your writing room, certainly no TV or videogames for you to fool around with.”

14. Stick to your own style. “One cannot imitate a writer’s approach to a particular genre, no matter how simple what that writer is doing may seem.”

15. Dig. “Stories are relics, part of an undiscovered pre-existing world. The writer’s job is to use the tools in his or her toolbox to get as much of each one out of the ground intact as possible.”

16. Take a break. “You’ll find reading your book over after a six-week layoff to be a strange, often exhilarating experience.”

17. Leave out the boring parts and kill your darlings. “(kill your darlings, kill your darlings, even when it breaks your egocentric little scribbler’s heart, kill your darlings.)”

18. The research shouldn’t overshadow the story. “Remember that word back. That’s where the research belongs: as far in the background and the back story as you can get it.”

19. You become a writer simply by reading and writing. “You learn best by reading a lot and writing a lot, and the most valuable lessons of all are the ones you teach yourself.”

20. Writing is about getting happy. “Writing isn’t about making money, getting famous, getting dates, getting laid or making friends. Writing is magic, as much as the water of life as any other creative art. The water is free. So drink.”

See a fuller exposition of King’s writing wisdom at Barnes & Noble’s blog.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2014.

Related Content:

7 Tips From Ernest Hemingway on How to Write Fiction

Kurt Vonnegut’s 8 Tips on How to Write a Good Short Story

Stephen King’s Top 10 All-Time Favorite Books

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness