It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child. — Pablo Picasso

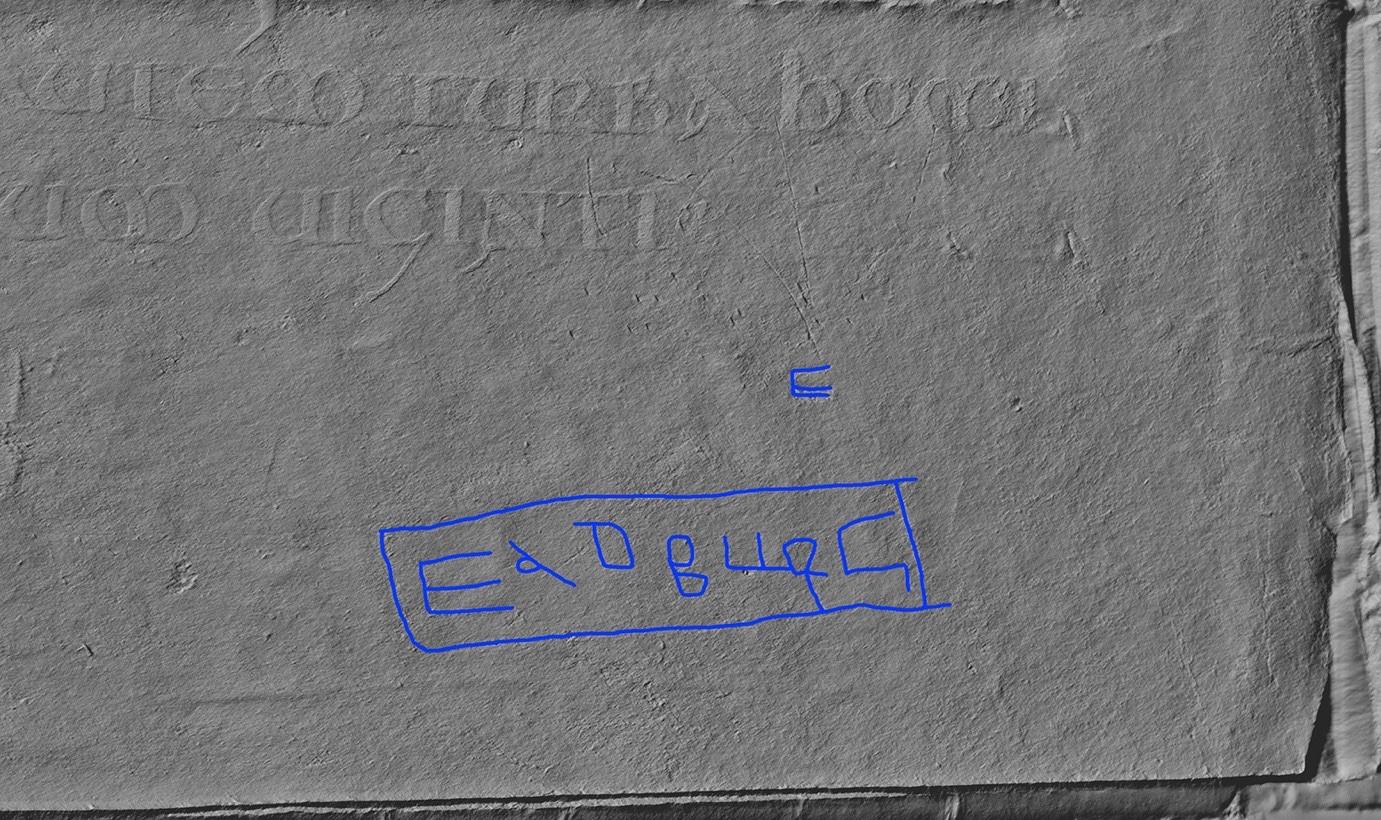

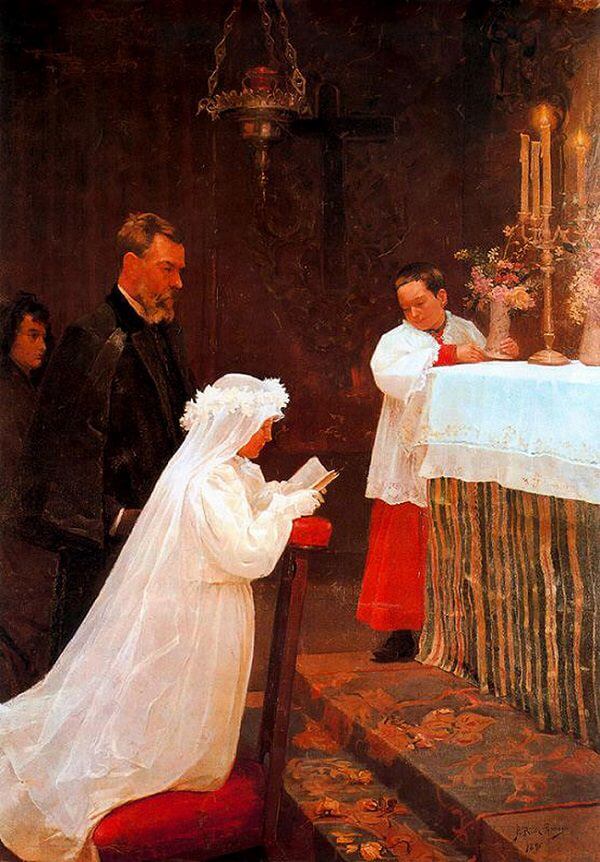

We think it’s safe to say that most of us have a preconceived notion of Picasso’s style, and The First Communion, above, isn’t it.

Picasso was just 15 when he completed this large-scale oil, having lost his 7‑year-old sister, Conchita, to diphtheria one year before.

The stricken young artist had attempted to bargain with God, vowing to give up painting if she was spared. As Arianna Huffington writes in the biography Picasso: Creator and Destroyer:

…he was torn between wanting her saved and wanting her dead so that his gift would be saved. When she died, he decided that God was evil and destiny an enemy. At the same time, he was convinced that it was his ambivalence that had made it possible for God to kill Conchita. His guilt was enormous—the other side of his belief in his powers to affect the world around him. And it was compounded by his almost magical conviction that his little sister’s death had released him to be a painter and follow the call of the powers he had been given, whatever the consequences.

If there’s evil at work in the “First Communion,” he keeps it under wraps. All eyes are on the rapt young communicant, embodied in his surviving sister, Lola, in a snowy veil and gown.

Their father, painter and drawing professor José Ruiz y Blasco, assumes the part of the girl’s father or godfather, a solemn witness to this rite of passage.

Ruiz y Blasco provided instruction and championed his son’s gift. He encouraged him to enter the “First Communion,” and later, “Science and Charity” (in which he appears as the doctor) in the Exposicion de Bellas Artes, a competition and exhibition opportunity for emerging artists.

Picasso later remarked that “every time I draw a man, I think of my father. To me, man is Don José, and will be all my life…”

Ruiz y Blasco, convinced that Picasso’s talent would bring success as a naturalistic painter of classical scenes and portraits, was deeply disappointed when his teenaged son began blowing off class at Madrid’s prestigious Academia Real de San Fernando.

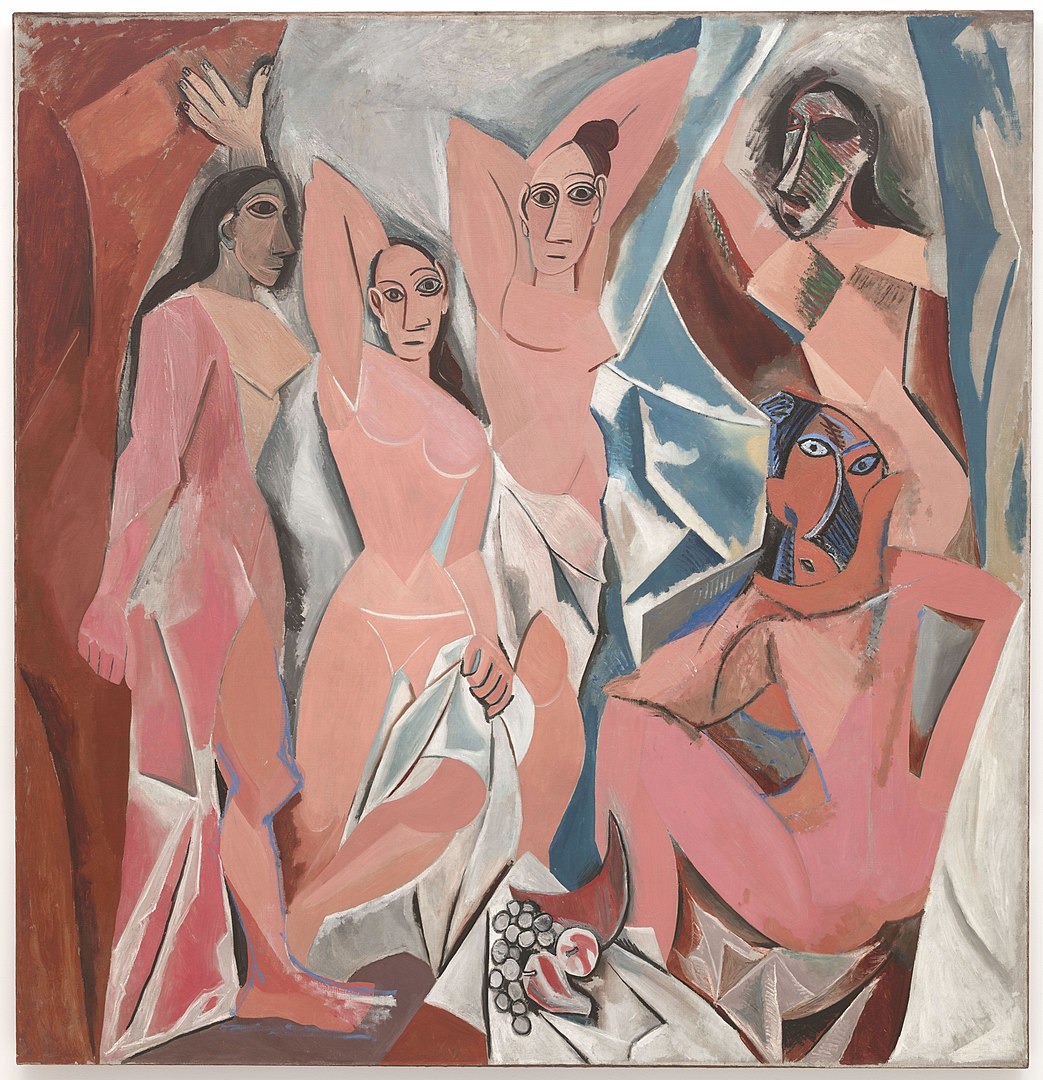

Just imagine how he reacted to the scandalous Cubist vision of “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” unveiled a mere eleven years after the “First Communion.”

The rest is history.

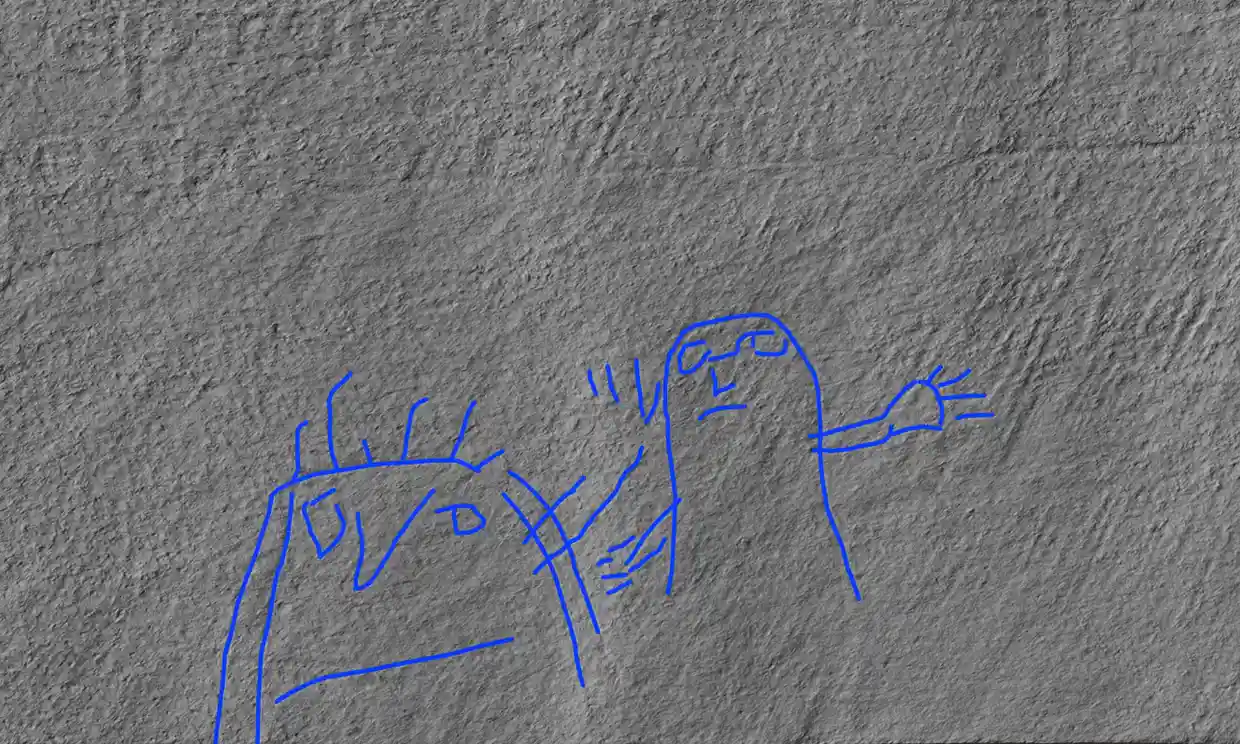

Just for fun, we invited the free online AI image generator Craiyon (formerly known as DALL‑E Mini) to have a go using the prompt “Picasso First Communion”.

The results should surprise no one.

Related Content

How To Understand a Picasso Painting: A Video Primer

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.