In the fall of 1998, pop music changed forever — or at least it seems that way today, a quarter-century later. The epochal event in question was the release of Cher’s comeback hit “Believe,” of whose jaggedly fractured vocal glissando no listener had heard the likes of before. “The glow-and-flutter of Cher’s voice at key points in the song announced its own technological artifice,” writes critic Simon Reynolds at Pitchfork, “a blend of posthuman perfection and angelic transcendence ideal for the vague religiosity of the chorus.” As for how that effect had been achieved, only the tech-savviest studio professionals would have suspected a creative misuse of Auto-Tune, a popular digital audio processing tool brought to market the year before.

As its name suggests, Auto-Tune was designed to keep a musical performance in tune automatically. This capability owes to the efforts of one Andy Hildebrand, a classical flute virtuoso turned oil-extraction engineer turned music-technology entrepreneur. Employing the same mathematical acumen he’d used to assist the likes of Exxon in determining the location of prime drilling sites from processed sonar data, he figured out a vast simplification of the calculations theoretically required for an algorithm to put a real vocal recording into a particular key.

Rapidly adopted throughout the music industry, Hildebrand’s invention soon became a generic trademark, like Kleenex, Jell‑O, or Google. Even if a studio wasn’t using Auto-Tune, it was almost certainly auto-tuning, and with such subtlety that listeners never noticed.

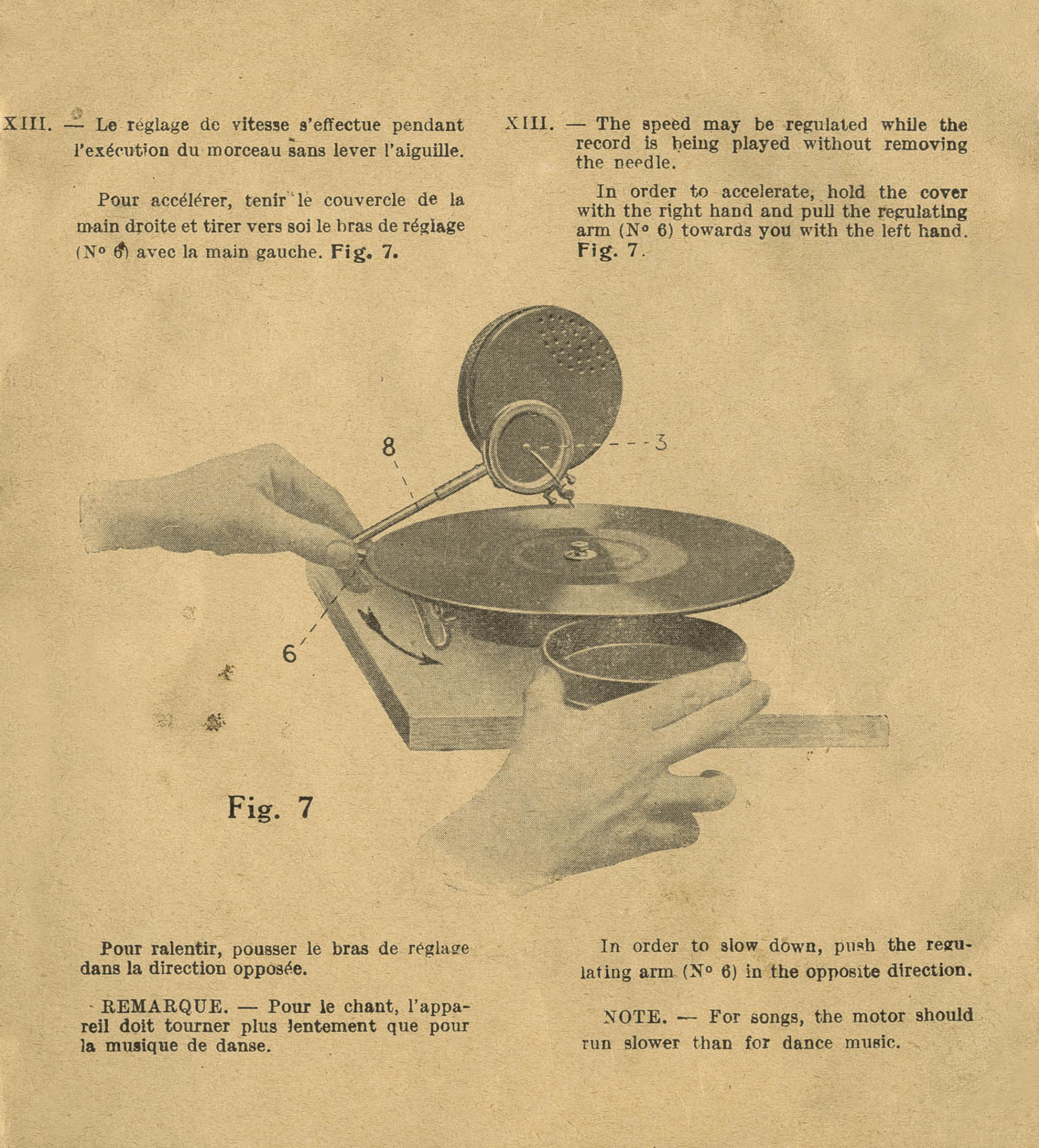

The producers of “Believe,” for their part, turned the subtlety (or, technically, the “smoothness”) down to zero. In an attempt to keep that discovery a secret, they claimed at first to have used a vocoder, a synthesizer that converts the human voice into manipulable analog or digital signals. Some would also have suspected the even more venerable talkbox, which had been made well-known in the seventies and eighties by Earth, Wind & Fire, Stevie Wonder, and Roger Troutman of Zapp. Though the “Cher effect,” as it was known for a time, could plausibly be regarded as an aesthetic descendant of those devices, it had an entirely different technological basis. A few years after that basis became widely understood, conspicuous Auto-Tune became ubiquitous, not just in dance music but also in hip-hop, whose artists (not least Rappa Ternt Sanga T‑Pain) used Auto-Tune to steer their genre straight into the currents of mainstream pop, if not always to high critical acclaim.

Used as intended, Auto-Tune constituted a godsend for music producers working with any singer less freakishly skilled than, say, Freddie Mercury. Producer-Youtuber Rick Beato admits as much in the video just above, though given his classic rock- and jazz-oriented tastes, it doesn’t come as a surprise also to hear him lament the technology’s overuse. But for those willing to take it to ever-further extremes, Auto-Tune has given rise to previously unimagined subgenres, bringing (as emphasized in a recent Arte documentary) the universal language of melody into the linguistically fragmented arena of global hip-hop. As a means of generating “digital soul, for digital beings, leading digital lives,” in Reynolds’ words, Auto-Tune does reflect our time, for better or for worse. Its detractors can at least take some consolation in the fact that recent releases have come with something called a “humanize knob.”

Related content:

The Evolution of Music: 40,000 Years of Music History Covered in 8 Minutes

How the Yamaha DX7 Digital Synthesizer Defined the Sound of 1980s Music

How Computers Ruined Rock Music

Brian Eno on the Loss of Humanity in Modern Music

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.