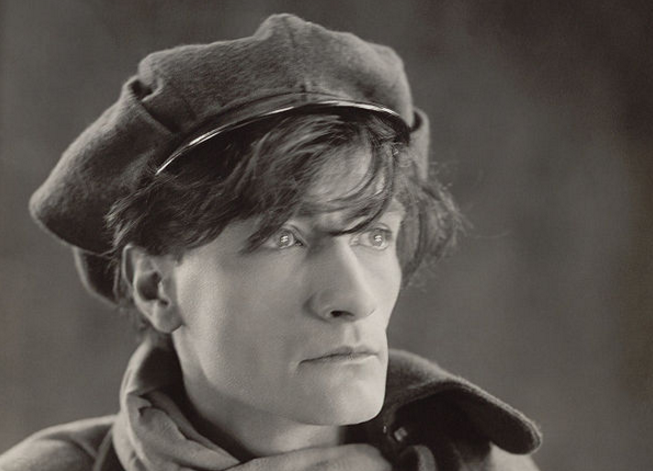

George Bernard Shaw once called Mark Twain “the American Voltaire,” and like the inspired French satirist, Twain seems to have something to say to every age, from his own to ours. But if Twain is Voltaire, to whom do we compare Bill Murray? Only posterity can properly assess Murray’s considerable impact on our culture, but his current role as everyone’s favorite pleasant surprise will surely figure largely in his historical portrait. Of Murray’s many random acts of kindness—which include “popping in on random karaoke nights, or doing dishes at other people’s house parties, or crashing wedding photo shoots”—he has also taken to surprising us with readings from American literary greats: from Cole Porter, to Wallace Stevens, to Emily Dickinson.

Just above see Murray read an excerpt from American great Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Murray’s appearance at the 1996 Barnes & Noble event apparently came as a surprise to the audience—and to himself. The excerpt he reads might also surprise many readers of Twain’s classic, who probably won’t find it in their copies of the novel. These passages were originally published in Life on the Mississippi but reinserted—“correctly, I guess,” Murray shrugs—into Huck Finn in Random House’s 1996 republication of the novel, marketed as “the only comprehensive edition.” (Read a publication history and summary of the changes in this brief, unsympathetic review of the re-edited text.)

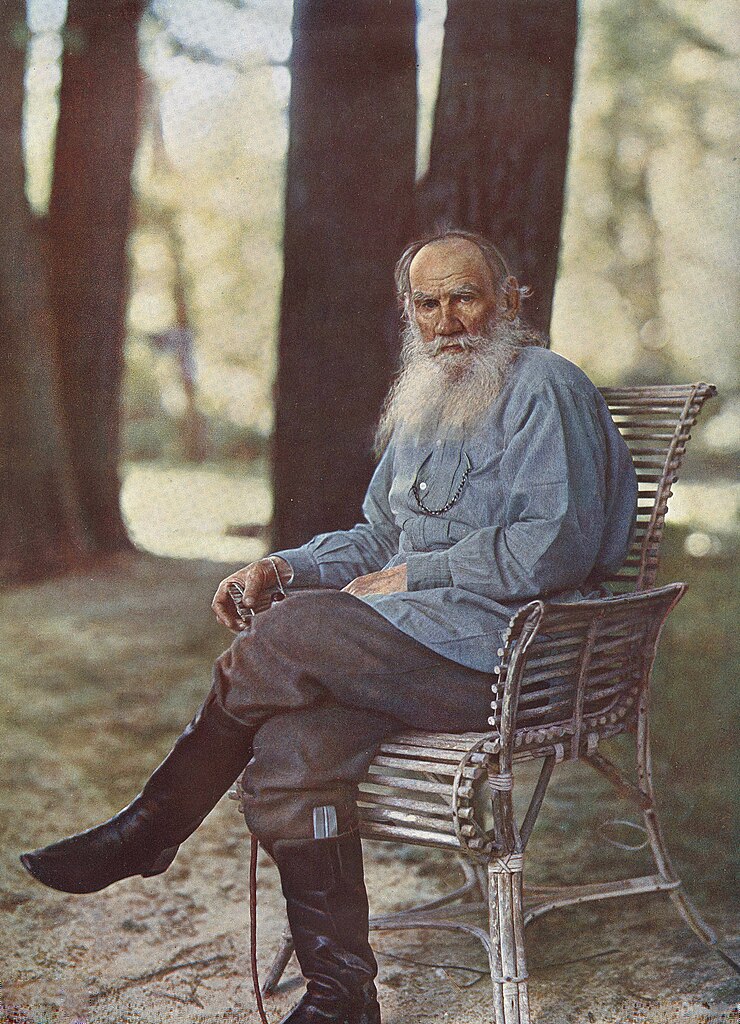

1996 was an interesting year for Twain’s novel. Long at the center of debates over racial sensitivity in public education, and banned many times over, the book figured prominently that year in a tense but fruitful meeting between parents and teachers in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. These discussions produced a new curricular approach that PBS outlines in its teaching guide “Huck Finn in Context,” which offers a variety of responses to the thorny pedagogy of “the ‘n’ word,” racial stereotyping, and reading satire. Beyond the issue of derogatory language, there also arose that year a pugnacious challenge to the book’s place in the American literary canon from novelist Jane Smiley. Smiley’s polemic prompted a lengthy rebuttal in The New York Times from Twain scholar Justin Kaplan.

Revisiting these debates reminds us of just how much we can take for granted a literary work’s social and cultural value. Smiley reminds us of the breadth of American literature by women writers that was pushed aside by critics to give male writers like Twain, Melville, and Poe pride of place. The various controversies surrounding the novel’s place in the classroom should remind us—as Toni Morrison has explained in depth—that racialized language does not strike all readers equally, and that this is a problem to be discussed openly, not ignored or banned out of sight. And Murray’s excellent dramatic reading of these re-inserted passages should remind us, over all, of the first reason we care about Huck Finn—not because of its political correctness or incorrectness, but because of its richness of character and dialogue.

After Murray’s reading above, New York Times writer Brent Staples introduces a distinguished panel of Shelby Foote, William Styron, Roy Blount, Jr., and Justin Kaplan. The five go on to discuss the “literary and historical significance” of the novel, confronting the controversies head-on. I think it’s a shame Jane Smiley wasn’t invited, or chose not to appear. In any case, you might be tempted to bolt after Bill Murray, but stick around for the writers. You won’t be disappointed.

You can find copies of Huck Finn in our Free eBooks and Free Audio Books collections.

Related Content:

Bill Murray Reads Great Poetry by Billy Collins, Cole Porter, and Sarah Manguso

Mark Twain Drafts the Ultimate Letter of Complaint (1905)

Mark Twain Wrote the First Book Ever Written With a Typewriter

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness