When people talk about “independent cinema” today, they seem, as often as not, to talk about a sensibility — we all know, on some level, what someone means when they tell us they “like indie films.” But the term has its roots, of course, not necessarily in independence of spirit, but in independence from systems. Now that technology has granted all of us the ability, at least in theory, to make any movie we want, this distinction has lost some of its meaning, but between about twenty and eighty years ago, the commercial establishments controlling production, distribution, and screening enjoyed their greatest solidity (and indeed, impenetrability). During that time, making a film independently meant making a fairly specific, often anti-Hollywood statement. But what about before then, when the medium of cinema itself had yet to take its full shape?

Not only does 1913’s The Student of Prague offer an entertaining example of independent film from an era before even Hollywood had become Hollywood, it has a place in history as the first independent film ever released. German writer Hanns Heinz Ewers and Danish director Stellan Rye (not to mention star Paul Wegener, he of the Golem trilogy) collaborated to bring to early cinematic life this 19th-century horror story of the titular student, a down-at-the-heels bon vivant who, besotted with a countess and determined to win her by any means necessary, makes a deal with a devilish sorcerer that will fulfill his every desire. The catch? He summons the student’s reflection out of the mirror and into reality. So empowered, this doppelgänger goes around wreaking havoc. Hardly the ostensibly high-minded material of “indie film” — let alone “foreign film” — from the past half-century or so, but The Student of Prague treats it with respect, arriving at the kind of uncompromising ending that might surprise even modern audiences. If you don’t watch it today, keep it bookmarked for Halloween viewing.

You can find The Student of Prague added to our big film collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Watch the German Expressionist Film, The Golem, with a Soundtrack by The Pixies’ Black Francis

Watch the Quintessential Vampire Film Nosferatu Free Online as Halloween Approaches

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis: Uncut & Restored

The Power of Silent Movies, with The Artist Director Michel Hazanavicius

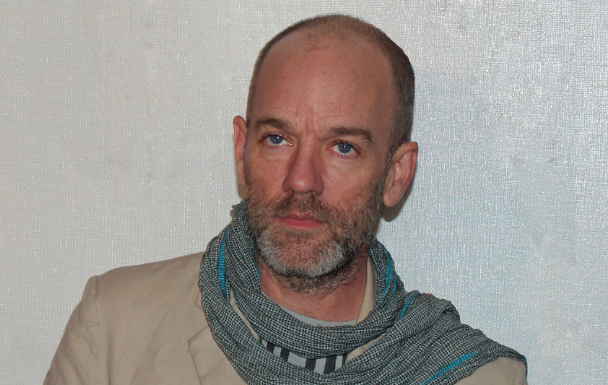

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.