News of the new, long-awaited but hardly expected Harper Lee novel, Go Set a Watchman—a sequel to the 1960’s To Kill a Mockingbird—has been met with varying degrees of skepticism, surely warranted given her late sister Alice and others’ characterization of Lee’s physical and mental decline. On the other hand, the novelist, it’s been reported, is “extremely hurt” by allegations that she has been pressured to publish. It would be a shame if the controversy over the publication of the novel eclipsed the novel itself. While it had become something of a truism that Harper Lee would only publish the one, great novel and never another, I for one greet this latest news with joy.

For one thing, circumstances aside, the new Harper Lee novel has the mass media doing something it rarely does anymore—talking about literary fiction. And for the thousands of school kids required to read To Kill a Mockingbird and wondering why they should bother, the conversation hopefully communicates that books still matter, and not just dystopian YA sci-fi and mass-market trade books about BDSM fantasies, but books about ordinary people in ordinary times and places. It’s a lesson Lee learned early. In a 2006 letter to Oprah Winfrey, published in O magazine, Lee wrote about her childhood experiences with reading, and being read to. She recalls arriving “in the first grade, literate,” because of her upbringing. She also acknowledges that “books were scarce”; her and her siblings early literacy meant they were “privileged” compared to other children, “mostly from rural areas,” and the “children of our African-American servants.”

While we may dismiss Lee’s contention that in “an abundant society where people have laptops, cell phones” and “iPods” they also have “minds like empty rooms” as the kvetching of a senior citizen, I doubt most people who respect Lee’s wisdom and good humor would do so lightly. Her poetic evocation of the tactile differences between books and gadgets alone should give us pause: “some things should only happen on soft pages, not cold metal.”

Read the full letter below.

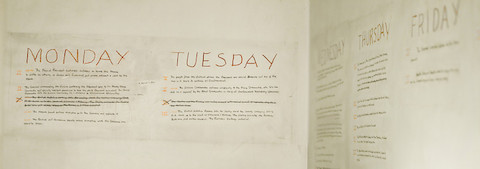

May 7, 2006

Dear Oprah,

Do you remember when you learned to read, or like me, can you not even remember a time when you didn’t know how? I must have learned from having been read to by my family. My sisters and brother, much older, read aloud to keep me from pestering them; my mother read me a story every day, usually a children’s classic, and my father read from the four newspapers he got through every evening. Then, of course, it was Uncle Wiggily at bedtime.

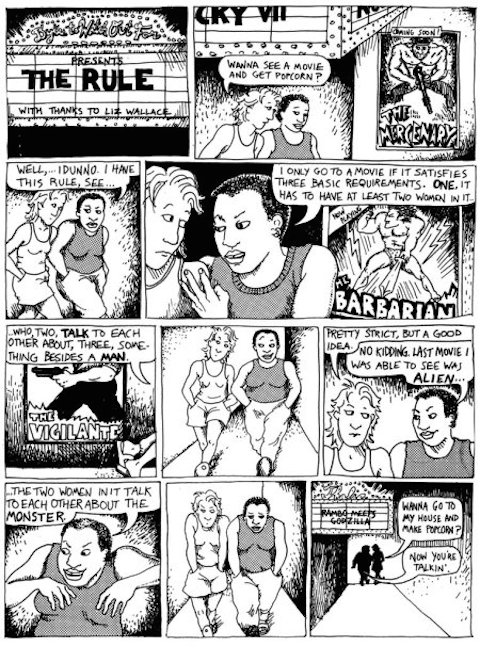

So I arrived in the first grade, literate, with a curious cultural assimilation of American history, romance, the Rover Boys, Rapunzel, and The Mobile Press. Early signs of genius? Far from it. Reading was an accomplishment I shared with several local contemporaries. Why this endemic precocity? Because in my hometown, a remote village in the early 1930s, youngsters had little to do but read. A movie? Not often — movies weren’t for small children. A park for games? Not a hope. We’re talking unpaved streets here, and the Depression.

Books were scarce. There was nothing you could call a public library, we were a hundred miles away from a department store’s books section, so we children began to circulate reading material among ourselves until each child had read another’s entire stock. There were long dry spells broken by the new Christmas books, which started the rounds again.

As we grew older, we began to realize what our books were worth: Anne of Green Gables was worth two Bobbsey Twins; two Rover Boys were an even swap for two Tom Swifts. Aesthetic frissons ran a poor second to the thrills of acquisition. The goal, a full set of a series, was attained only once by an individual of exceptional greed — he swapped his sister’s doll buggy.

We were privileged. There were children, mostly from rural areas, who had never looked into a book until they went to school. They had to be taught to read in the first grade, and we were impatient with them for having to catch up. We ignored them.

And it wasn’t until we were grown, some of us, that we discovered what had befallen the children of our African-American servants. In some of their schools, pupils learned to read three-to-one — three children to one book, which was more than likely a cast-off primer from a white grammar school. We seldom saw them until, older, they came to work for us.

Now, 75 years later in an abundant society where people have laptops, cell phones, iPods, and minds like empty rooms, I still plod along with books. Instant information is not for me. I prefer to search library stacks because when I work to learn something, I remember it.

And, Oprah, can you imagine curling up in bed to read a computer? Weeping for Anna Karenina and being terrified by Hannibal Lecter, entering the heart of darkness with Mistah Kurtz, having Holden Caulfield ring you up — some things should happen on soft pages, not cold metal.

The village of my childhood is gone, with it most of the book collectors, including the dodgy one who swapped his complete set of Seckatary Hawkinses for a shotgun and kept it until it was retrieved by an irate parent.

Now we are three in number and live hundreds of miles away from each other. We still keep in touch by telephone conversations of recurrent theme: “What is your name again?” followed by “What are you reading?” We don’t always remember.

Much love,

Harper

via Letters of Note

Related Content:

William Faulkner Reads His Nobel Prize Speech

Download 20 Popular High School Books Available as Free eBooks & Audio Books

The Books You Think Every Intelligent Person Should Read: Crime and Punishment, Moby-Dick & Beyond (Many Free Online)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness