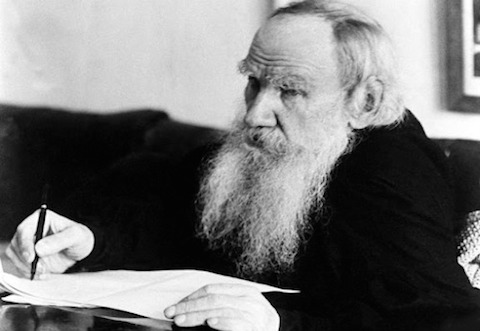

The U.S. government’s so-called “War on Drugs” predates Richard Nixon’s coinage of the term in 1971 by many decades, though it is under his administration that it assumed its current scope and character. Before Woodstock and Vietnam, before the creation of the DEA in 1973, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics—headed by “America’s first drug czar,” Commissioner Harry J. Anslinger, from 1930 to 1962—waged its own war, at first primarily on marijuana, and, to a great degree, on jazz musicians and jazz culture. Anslinger came to power in the era of Reefer Madness, the title of a rather ridiculous 1938 anti-drug film that has come to stand in for hyperbolic anti-pot paranoia of the ’30s and ’40s more generally. Much of that madness was the Commissioner’s special creation.

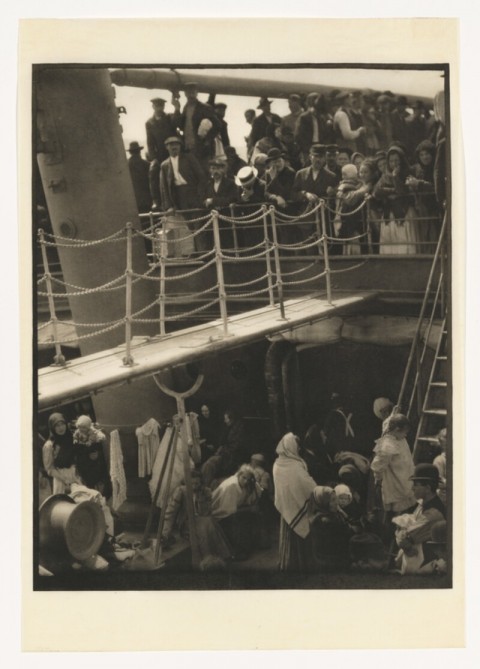

Like so much of the post-Nixon drug war, Anslinger staged his campaign as a moral crusade against certain kinds of users: dissidents, the counterculture, and especially immigrants and blacks. According to Alexander Cockburn’s Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs, and the Press, Anslinger’s “first major campaign was to criminalize the drug commonly known as hemp. But Anslinger renamed it ‘marijuana’ to associate it with Mexican laborers,” and claimed that the drug “can arouse in blacks and Hispanics a state of menacing fury or homicidal attack.” Anslinger “became the prime shaper of American attitudes to drug addiction.” And like later despisers of rock ‘n’ roll and hip-hop, Anslinger’s hatred of jazz motivated many of his targeted attacks.

Ansligner linked marijuana with jazz and persecuted many black musicians, including Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie and Duke Ellington. Louis Armstrong was also arrested on drug charges, and Anslinger made sure his name was smeared in the press. In Congress he testified that “[c]oloreds with big lips lure white women with jazz and marijuana.”

“Marijuana is taken by… musicians,” he told Congress in 1937, “And I’m not speaking about good musicians, but the jazz type.” Although the La Guardia Committee would refute almost everything Anslinger testified to about the effects of smoking pot, the damage was already done. (Anslinger’s prosecution of jazz musicians, particularly Louis Armstrong—paralleled that of another power-mad, paranoid bureaucrat, J. Edgar Hoover.)

Anslinger did not simply dislike jazz. He feared it. “It sounded,” he wrote, “like the jungles in the dead of night.” In jazz, “unbelievably ancient indecent rites of the East Indies are resurrected.” And the lives of jazz musicians “reek of filth.” And yet, writes Johann Hari in his book Chasing the Scream (excerpted in Politico), his campaign largely failed because of the jazz world’s “absolute solidarity” in opposition to it. “In the end,” writes Hari, “the Treasury Department told Anslinger he was wasting his time.” And so, “he scaled down his focus until it settled like a laser on one single target—perhaps the greatest female jazz vocalist there ever was,” Billie Holiday.

Anyone with even the most cursory knowledge about Holiday knows she had a drug problem in desperate need of treatment. And, of course, Holiday wasn’t addicted to a relatively harmless substance like marijuana, but to heroin, which—along with alcohol abuse—eventually lead to her death. Yet, as Cockburn writes, Anslinger had “hammer[ed] home his view that [drug addiction] was not… treatable,” but “could only be suppressed by harsh criminal sanctions.” Accordingly, he “hunted” Holiday—in Hari’s apt description—sending agents after her when he heard “whispers that she was using heroin, and—after she flatly refused to be silent about racism.”

Recruiting a black agent, Jimmy Fletcher, for the job, Anslinger began his attacks on Holiday in 1939. Fletcher shadowed Holiday for years, and became protective, eventually, “it seems,” writes Hari, “fall[ing] in love with her.” But Anslinger broke the case through Holliday’s viciously abusive husband, Louis McKay, who agreed to inform on her—something no fellow musician would do. In May of 1947, Holiday was arrested and put on trial for possession of narcotics. “Sick and alone,” writes Hettie Jones in Big Star Fallin’ Mama: Five Women in Black Music, “she signed away her right to a lawyer and no one advised her to do otherwise.” Promised a “hospital cure in return for a plea of guilty,” she was instead “convicted as a ‘criminal defendant,’ and a ‘wrongdoer,’ and sentenced to a year and a day in the Federal Women’s Reformatory at Alderson, West Virginia.”

After her release, Holiday was stripped of her cabaret license, restricted from singing in “all the jazz clubs in the United States… on the grounds,” writes Hari, “that listening to her might harm the morals of the public.” Two years after her first conviction, Anslinger recruited another agent, a sadist named George White, who was all too happy take Holiday down. He did so in 1949 at the Mark Twain Hotel in San Francisco—“one of the few places she could still perform”—arresting her without a warrant and with what were very likely planted drugs. White apparently “had a long history of planting drugs on women” and “may well have been high when he busted Billie for getting high.” (See the declassified case against her here. Her manager John Levy is erroneously referred to as her “husband” and called “Joseph Levy.”)

A jury refused to convict, but Anslinger gloried in the toll his campaign had taken. “She had slipped from the peak of her fame,” he wrote, “her voice was cracking.” After her death in 1959, he wrote callously, “for her, there would be no more ‘Good Morning Heartache.’” For her part, though Holiday “didn’t blame Anslinger’s agents as individuals; she blamed the drug war,” writing in her autobiography, “Imagine if the government chased sick people with diabetes, put a tax on insulin and drove it into the black market… then sent them to jail…. We do practically the same thing every day in the week to sick people hooked on drugs.”

Many jazz musicians, but especially Holiday, paid dearly for Anslinger and the Federal Bureau of Narcotics’ “war on drugs.” Hari documents the “race panic” that underlay most of Anslinger’s actions and the egregious double standard he applied, including a “friendly chat” he had with Judy Garland over her heroin addiction and kid gloves treatment of a “Washington society hostess,” in contrast to his relentless prosecution of Holiday. His persecution of Holliday and others was accompanied by a propaganda campaign that demonized “the Negro population” as dangerous addicts. As Hari points out, Anslinger “did not create these underlying trends,” but he promoted racist fictions and manipulated them to his advantage. And his singling out of cultures and groups he personally disliked and feared as special targets for vigorous, prejudicial prosecution helped set the agenda for anti-drug legislation and cultural attitudes in every decade since he decided to go after jazz and Billie Holiday.

Hari’s book, Chasing the Scream, is now available on Amazon.

Related Content:

Billie Holiday — The Life and Artistry of Lady Day: The Complete Film

Duke Ellington’s Symphony in Black, Starring a 19-Year-old Billie Holiday

Curious Alice — The 1971 Anti-Drug Movie Based on Alice in Wonderland That Made Drugs Look Like Fun

Louis Armstrong Plays Historic Cold War Concerts in East Berlin & Budapest (1965)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness