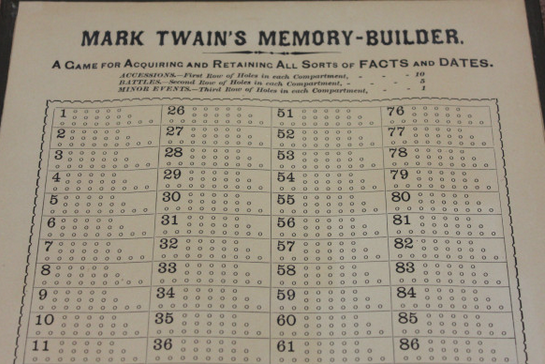

Mark Twain wrote The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, of course, but like any good luminary of 19th-century America, he also put together a few inventions on the side. These non-literary achievements of Twain’s included an “Improvement in Adjustable and Detachable Straps for Garments” (as the patent calls it) meant to replace suspenders, a “self-pasting” scrapbook”, and the “Memory-Builder, a game for acquiring and retaining all sorts of facts and dates.”

“Twain believed that memorization — a common strategy of 19th-century schooling — was a worthy, if tiresome, pursuit, and looked for ways to make it more interesting for annoyed students,” writes Slate’s Rebecca Onion. This line of thinking led him to create the Memory-Builder, which he described as a “game which shall fill the children’s heads with dates without study” in an 1883 letter to a friend. He explained the background of his educational philosophy in much fuller detail in a 1914 piece from Harper’s magazine:

Sixteen years ago when my children were little creatures the governess was trying to hammer some primer histories into their heads. Part of this fun — if you like to call it that — consisted in the memorizing of the accession dates of the thirty-seven personages who had ruled England from the Conqueror down. These little people found it a bitter, hard contract. It was all dates, they all looked alike, and they wouldn’t stick. Day after day of the summer vacation dribbled by, and still the kings held the fort; the children couldn’t conquer any six of them.

This experience gave rise to a couple of different learning methods, of which the Memory-Builder (patented in 1885) would prove the best-known. Though Twain worked out a way to play it on a cribbage board converted into a historical timeline, you can play a technologically much-updated but materially identical version of the game online (with the same cribbage pins and the same strangely intense focus on those royals) at the web site of the University of Oregon’s library. Alternatively, you can play an adaptation that deals with the life and times of Twain himself at the University of Virginia’s web site.

Whether or not the Memory-Builder can help you learn your history, you’ll have to find out for yourself. Not having caught on at the time, Twain’s game didn’t get far out of the prototype stage, but the idea behind it has survived in the form of one of Twain’s many so-very-quotable quotes: “I have never let my schooling interfere with my education.” Something tells me he’d approve of seeing his game on the internet, surely the tool that has done more to get education into the learner’s own hands than anything else in human history so far. (Um, have you seen our list of 1100 Free Online Courses?)

via Slate

Related Content:

Mark Twain Wrote the First Book Ever Written With a Typewriter

Mark Twain Shirtless in 1883 Photo

Mark Twain Captured on Film by Thomas Edison in 1909. It’s the Only Known Footage of the Author.

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture as well as the video series The City in Cinema and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.