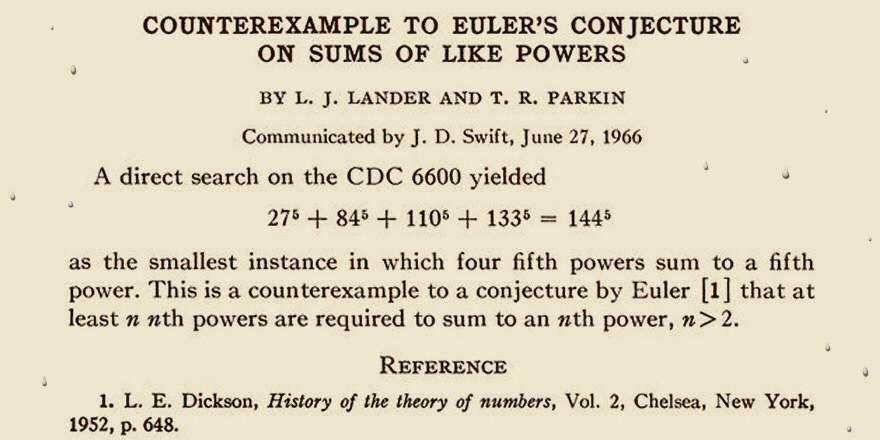

Just a few miles from where I live on Los Angeles’ Olympic Boulevard stands the Helios House, which, the name notwithstanding, is a gas station — and quite a striking one. Made of stainless steel triangles, it looks like a piece of very early computer-generated imagery brought into the modern physical world. The Helios House introduced me to the concept of the architecturally forward gas station, but, built in 2007, it actually came late to the game: witness, for instance, Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1956 R.W. Lindholm Service Station in Cloquet, Minnesota (above and below).

“In the early 1930s, Wright began developing concepts for Broadacre City, a city spread out to the point where it would be ‘everywhere and nowhere,’” we wrote when we first posted about the building in 2011.

“The design for the Lindholm gas station came directly from this conceptual project.” Alas, writes The Atlantic’s Daniel Fromson, Wright’s ambitious design didn’t catch on: “Certain elements, such as gas pumps hanging from an overhead canopy—intended to boost efficiency and save space—were prohibited by Cloquet fire bylaws (although, coincidentally, hanging pumps eventually became popular in Japan). The unorthodox station was also estimated by one trade publication to have cost two to three times as much as a standard design.”

But Wright doesn’t stand alone among the modernist masters in having done gas-station work. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, another architect with a penchant for reimagining the elements of the city, put his hand (or at least those of someone in his office ) to the task in 1969, coming up with the characteristically stripped-down Nuns’ Island gas station in the middle of Montreal’s Saint Lawrence River. Unlike the Lindholm Service Station, it no longer performs its intended function, but it does have a repurposed future as a community center. His other gas station, put up at the campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology where he headed the department of architecture, hasn’t survived at all.

But Oobject includes it in their list of the top fifteen modernist gas stations, which features buildings by Norman Foster and Arne Jacobsen and should make fine further reading if you’ve enjoyed this post. See also Flavorwire’s list of the world’s most beautiful gas stations, which names not only Wright and Mies van der Rohe’s work, but the Helios House, a few pieces of swooping midcentury glory in Los Angeles and Scandinavia, and a “Teapot Dome Service Station” shaped like exactly that. If you’re going to pay today’s gas prices, after all, you might as well fill up under an aesthetically notable structure.

Related Content:

Frank Lloyd Wright Reflects on Creativity, Nature and Religion in Rare 1957 Audio

The History of Western Architecture: From Ancient Greece to Rococo (A Free Online Course)

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater Animated

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.