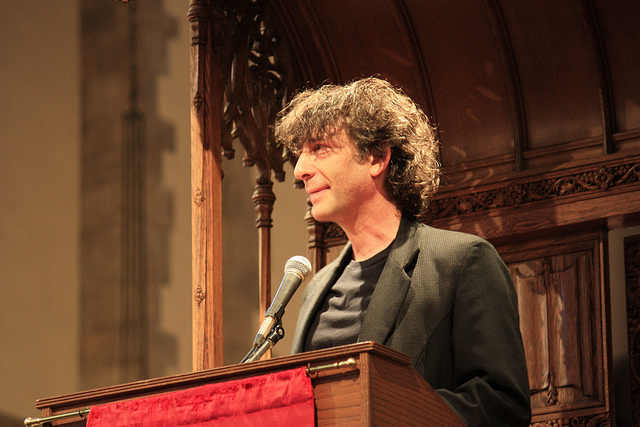

Image by Thierry Ehrmann, via Flickr Commons

Everybody knows Neil Gaiman, but they all know him best for different work: writing comic books like Sandman, novels like American Gods, television series like Neverwhere, movies like MirrorMask, an early biography of Duran Duran. What does all that — and everything else in the man’s prolific career — have in common? Stories. Every piece of work Gaiman does involves him telling a story of one kind or another, and so his profile in the culture has risen to great heights as, simply, a storyteller. That made him just the right man for the job when the Long Now Foundation, with its mission of thinking far back into the past and far forward into the future, needed someone to talk about how certain stories survive through both those time frames and beyond.

“Do stories grow?” Gaiman asks his years-in-the-making Long Now lecture, listenable on Soundcloud right below or viewable as a video here. “Pretty obviously — anybody who has ever heard a joke being passed on from one person to another knows that they can grow, they can change. Can stories reproduce? Well, yes. Not spontaneously, obviously — they tend to need people as vectors. We are the media in which they reproduce; we are their petri dishes.” He goes on to bring out examples from cave paintings, to secret retellings of Gone with the Wind in a Nazi concentration camp, to a warning to future generations not to dig into nuclear waste sites — designed for passage into the minds of posterity as a robustly crafted story.

Stories, writes the Long Now Foundation founder Stewart Brand, “outcompete other stories by hanging over time. They make it from medium to medium — from oral to written to film and beyond. They lose uninteresting elements but hold on to the most compelling bits or even add some.” He knows that, Gaiman knows that, and I think that all of us who have told stories sense its truth on an instinctive level: “The most popular version of the Cinderella story (which may have originated long ago in China) has kept the gloriously unlikely glass slipper introduced by a careless French telling.”

Another beloved British teller of tales, Douglas Adams, also had thoughts on the almost biological nature of literature. “We were talking about The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” Gaiman recalled elsewhere, “which was something which resembled an iPad, long before it appeared. And I said when something like that happens, it’s going to be the death of the book. Douglas said no. Books are sharks.” And what did he mean by that? “Sharks have been around for a very long time. There were sharks before there were dinosaurs, and the reason sharks are still in the ocean is that nothing is better at being a shark than a shark.” So not only do the best stories evolve to last the longest, so do the forms they take.

You can find 18 stories by Neil Gaiman (all free) in this collection.

Related Content:

George Saunders Demystifies the Art of Storytelling in a Short Animated Documentary

48 Hours of Joseph Campbell Lectures Free Online: The Power of Myth & Storytelling

Neil Gaiman Reads “The Man Who Forgot Ray Bradbury”

Where Do Great Ideas Come From? Neil Gaiman Explains

Amanda Palmer Animates & Narrates Husband Neil Gaiman’s Unconscious Musings

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.