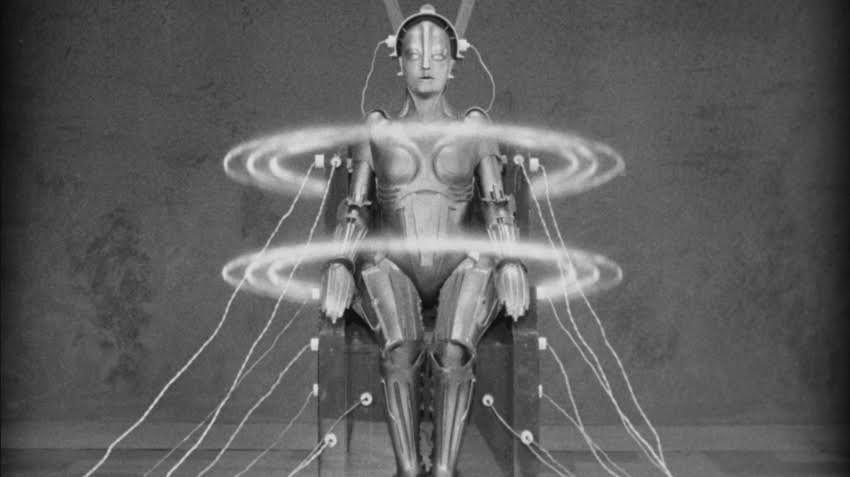

The Russian Revolution not only radically reshaped social and political institutions in the soon-to-be Soviet Union, but it also radicalized the arts. “The Romanovs, who ruled Russia for 300 years,” comments Glenn Altschuler at The Boston Globe, used “culture as an instrument of political control.” As the Bolsheviks swept away lumbering czarist elitism, they brought with them an avant-gardism that also sought to be populist and proletarian—spearheaded by such experimental artists as filmmaker Dziga Vertov, poet, futurist actor, and artist Vladimir Mayakovsky, and “suprematist” painter Kazimir Malevich. While many of these artists were denounced as bourgeois obscurantists when the dogmas of socialist realism became their own instruments of political control, for several years, the nascent Communist state produced some of the most forward-thinking art, music, dance, and film the world had yet seen.

That includes some of the first fully synthetic music ever made, created by innovative methods that predated synthesizers by several decades. We’ve likely all heard of the Theremin, for example, invented in 1919 by Soviet engineer Leon Theremin. By the 1930s, other inventive technologists and composers had begun to experiment with oscilloscopes and magnetic tape, cutting or drawing waveforms by hand to create synthetic sounds.

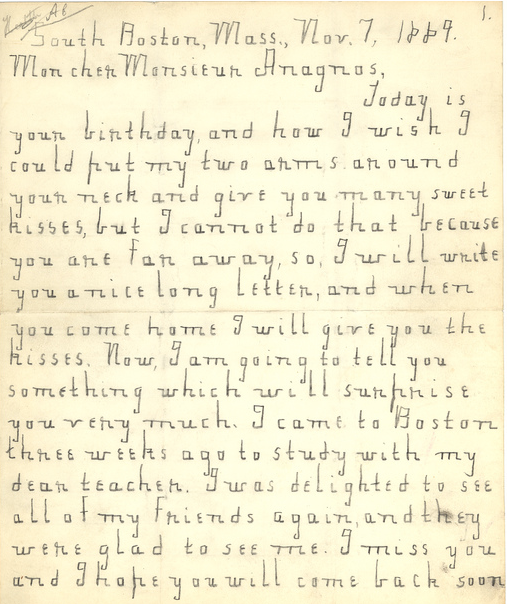

One avant-garde Soviet composer, Arseny Avraamov became inspired by the advent of sound recording technology in film. The process of optical sound uses an audio track recorded on a separate negative that runs parallel with the film (see it explained above). After the development of this technology, writes Paul Gallagher at Dangerous Minds, Bauhaus artist László Moholy-Nagy suggested that “a whole new world of abstract sound could be created from experimentation with the optical film sound track.”

Taking up the challenge after the first Russian sound film—1929’s The Five Year Plan—Avraamov “produced (possibly) the first short film with a hand-drawn synthetic soundtrack.” One very short example of his technique, at the top of the post, may not sound like much to us, but it preserves a fascinating technique and a look at what might have been had this technique, and others like it, borne more fruit. Monoskop describes Avraamov as “a composer, music theorist, performance instigator, expert in Caucusian folk music, [and] outspoken critic of the classical twelve-tone system.” He was also the commissar of a ministry set up to encourage “the development of a distinctly proletarian art and literature.” It’s not entirely clear how what he called “ornamental sound” techniques fit that purpose. But along with innovators like Evgeny Sholpo and Nikolai Voinov—whose fascinating experiments you can hear above and below—Avraamov showed that technologies generally used to deliver entertainment and propaganda to passive mass audiences could be manipulated by hand to create something entirely unique.

The experiments of these sound pioneers perhaps held little appeal for the average Russian, but they were enthusiastically written up in a 1936 issue of American magazine Modern Mechanix. “Voinov and Avraamov,” notes Gallagher, “briefly formed a research institute in Moscow, where they hoped to create synthetic voices and understand the musical language of geometric shapes. It didn’t last and, alas, closed within a year.”

Related Content:

Eight Free Films by Dziga Vertov, Creator of Soviet Avant-Garde Documentaries

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness