The history of the printed book stretches back well over a millennium, the title of the oldest known book currently being held by a Tang Dynasty work of the Diamond Sutra. But what about the most beautiful book? As a contender for that spot, Michael Goodman (previously featured here on Open Culture for his projects on the illustrations of Shakespeare and Dickens) has put forth the Kelmscott Chaucer, including the testimony of no less a literary figure than W.B. Yeats, who called it “the most beautiful of all printed books.” Goodman has also made the book freely available for our perusal on his new web site, The Kelmscott Chaucer Online.

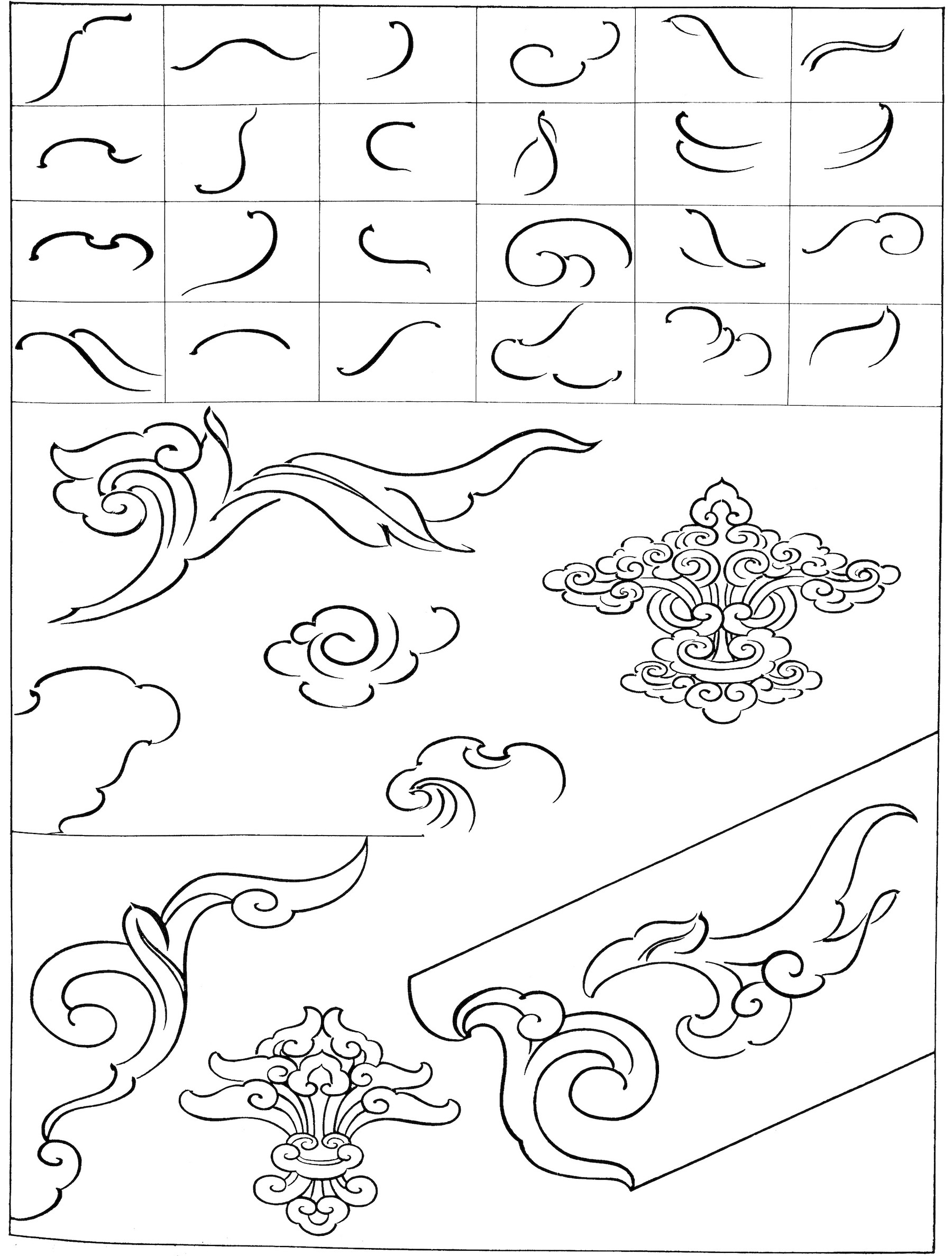

“William Morris, the nineteenth-century designer, social reformer and writer, founded the Kelmscott Press towards the end of his life,” says the web site of the British Library. “He wanted to revive the skills of hand printing, which mechanization had destroyed, and restore the quality achieved by the pioneers of printing in the 15th century.”

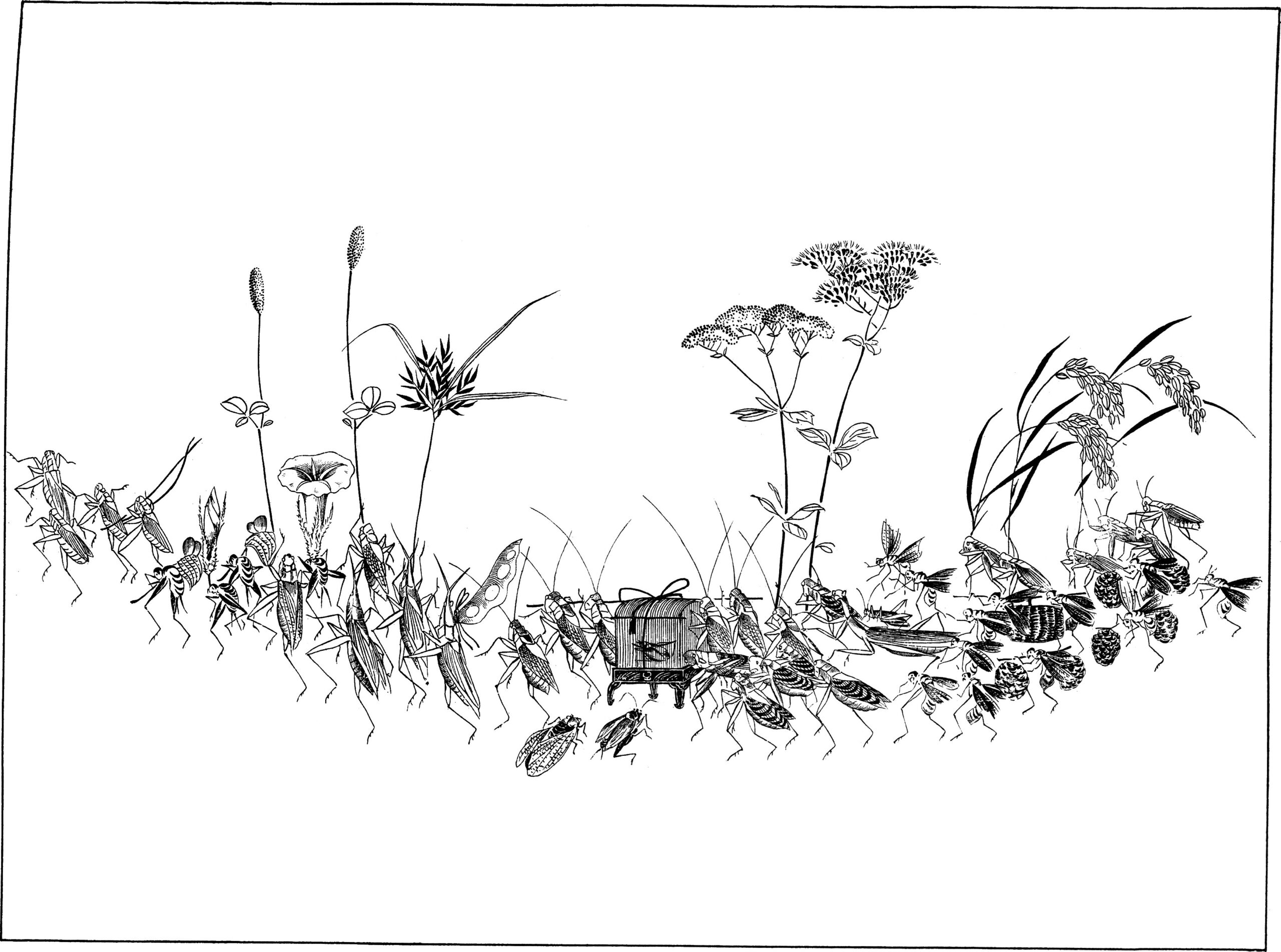

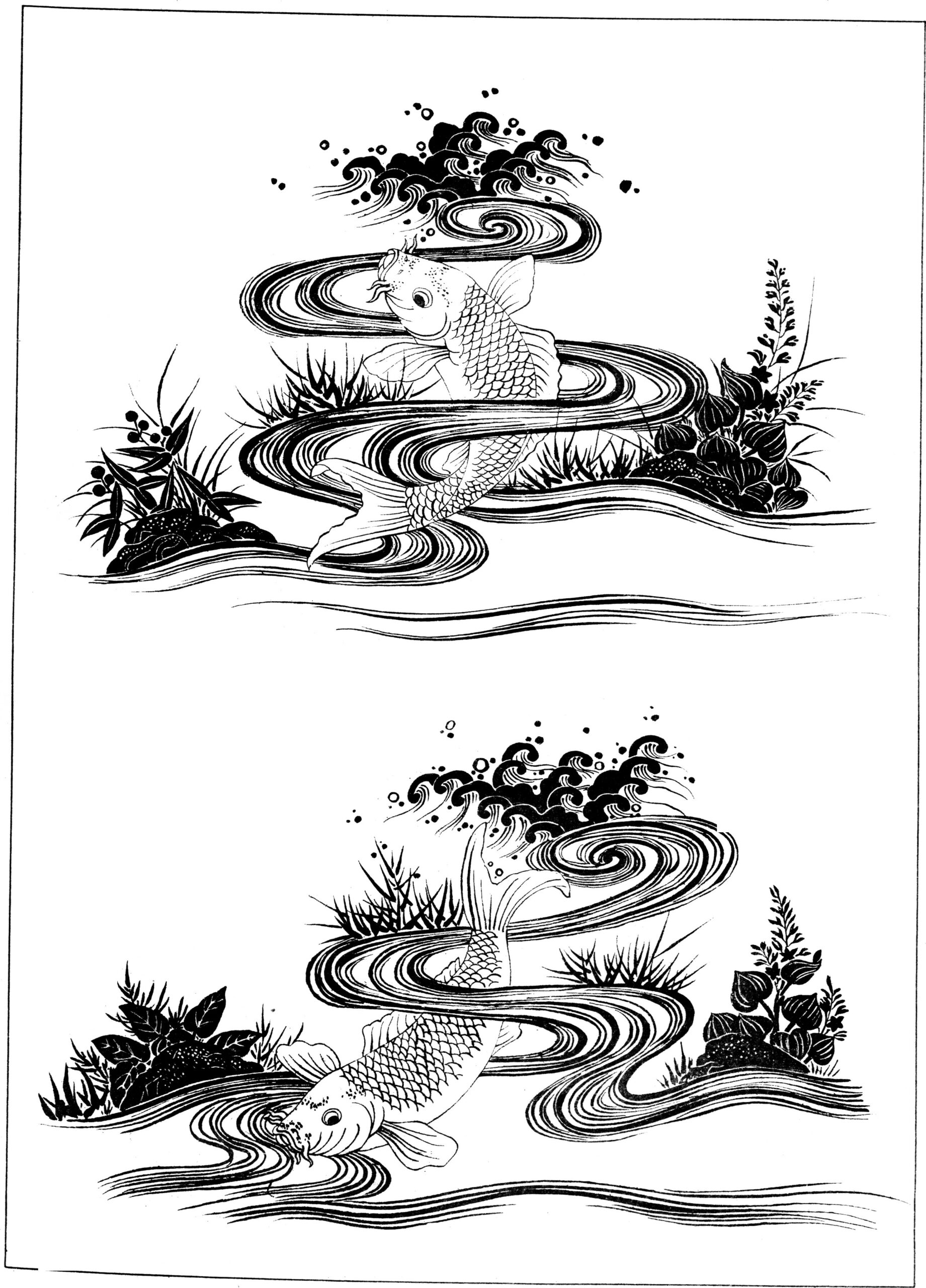

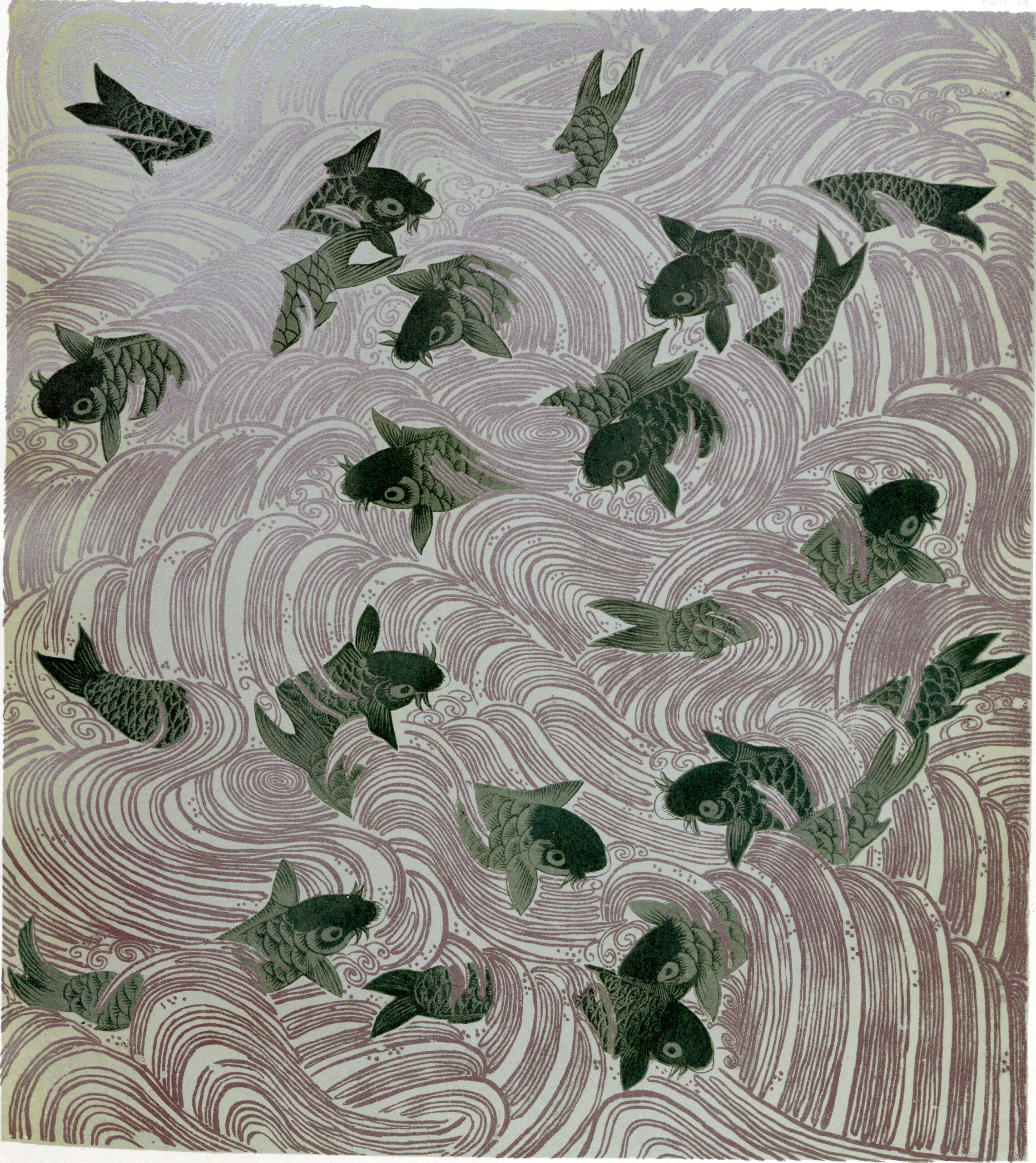

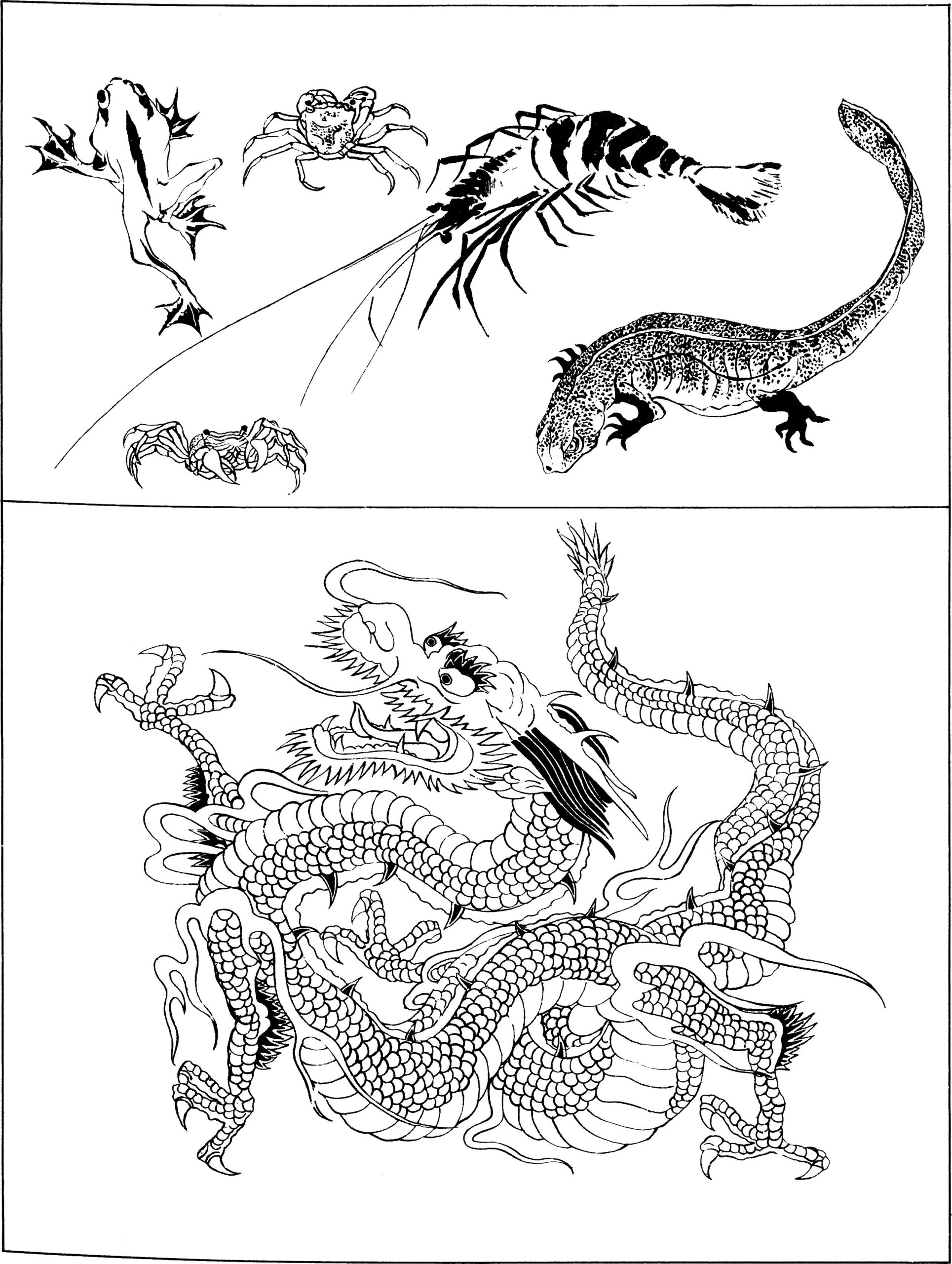

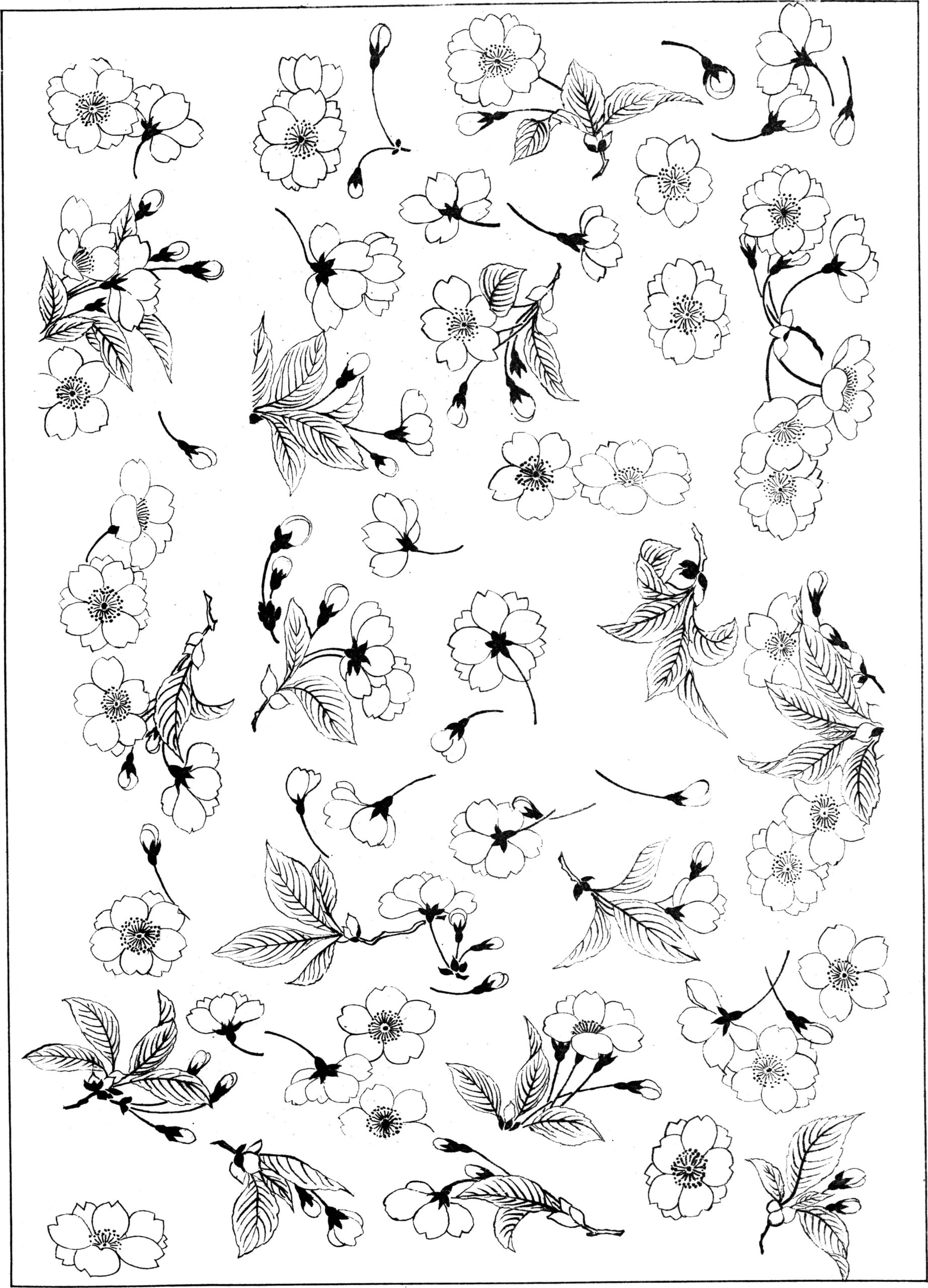

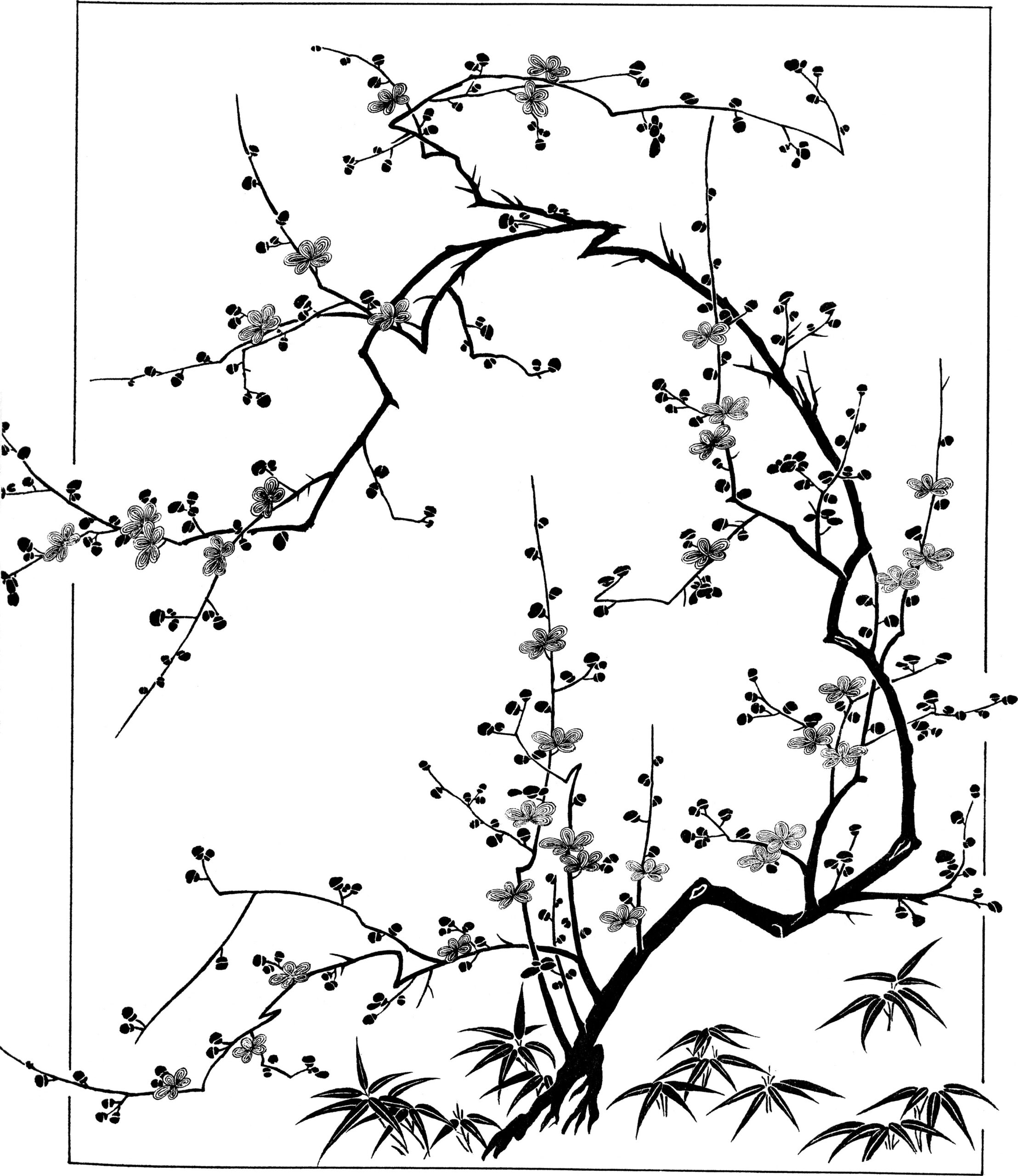

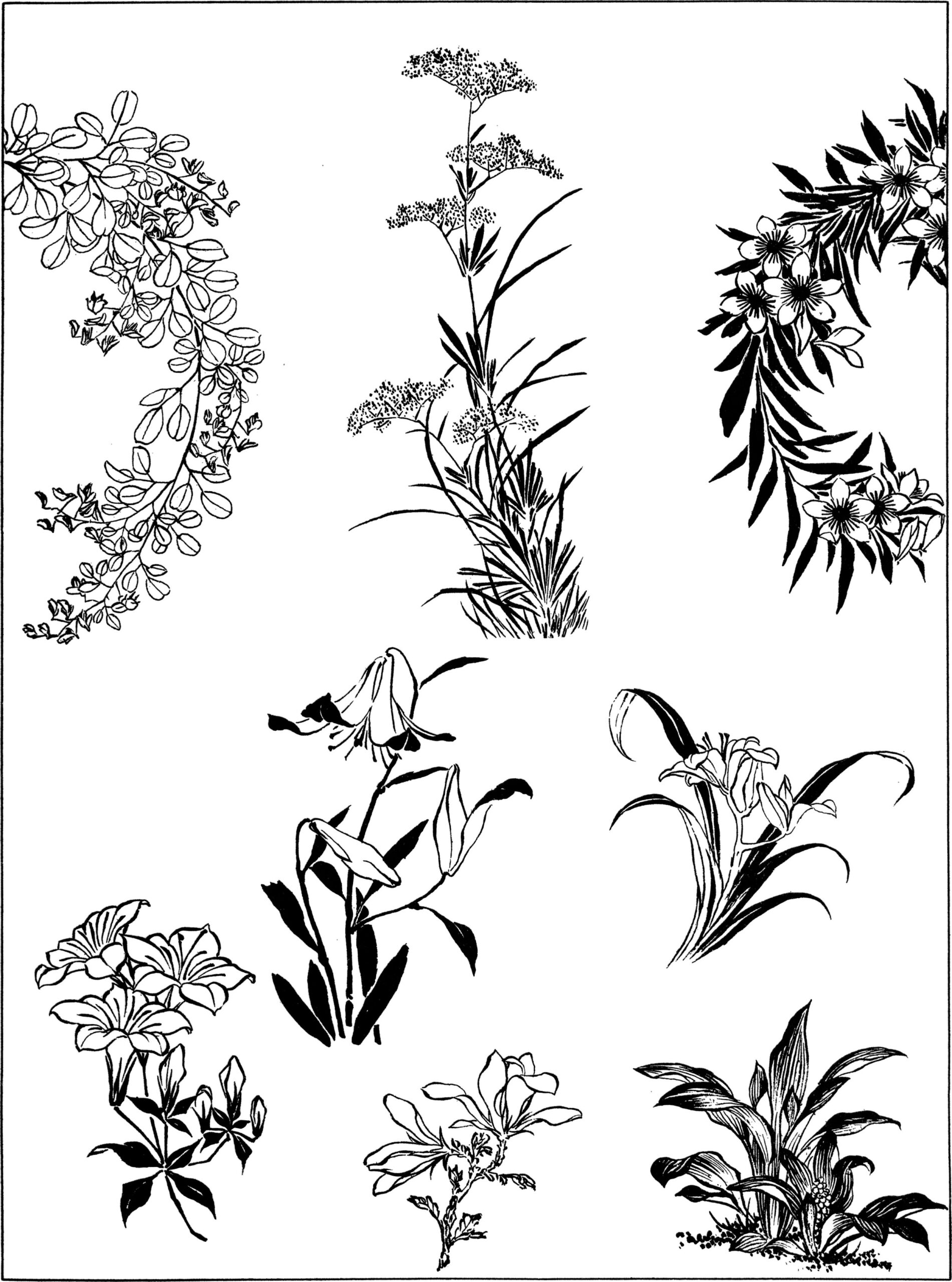

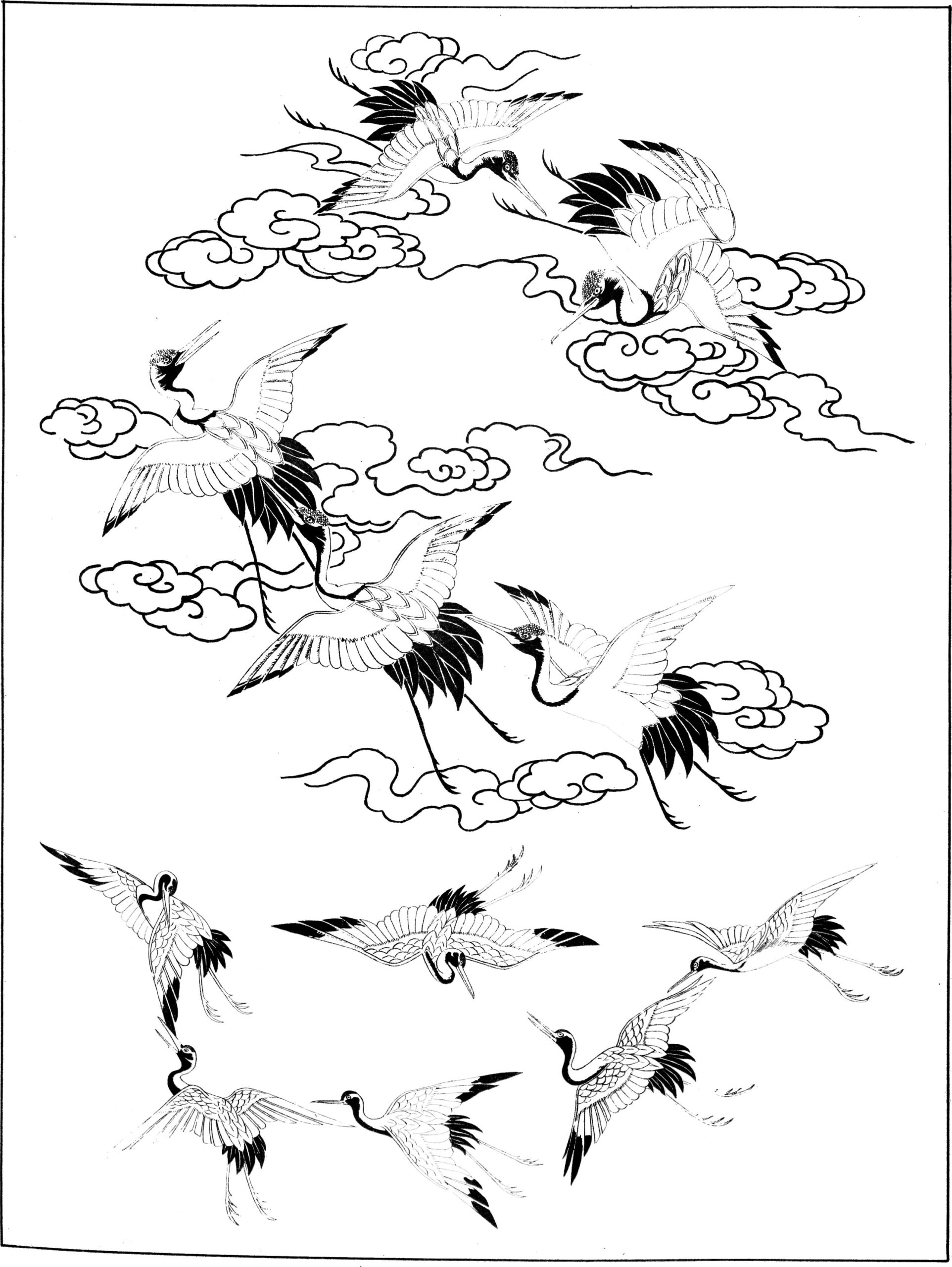

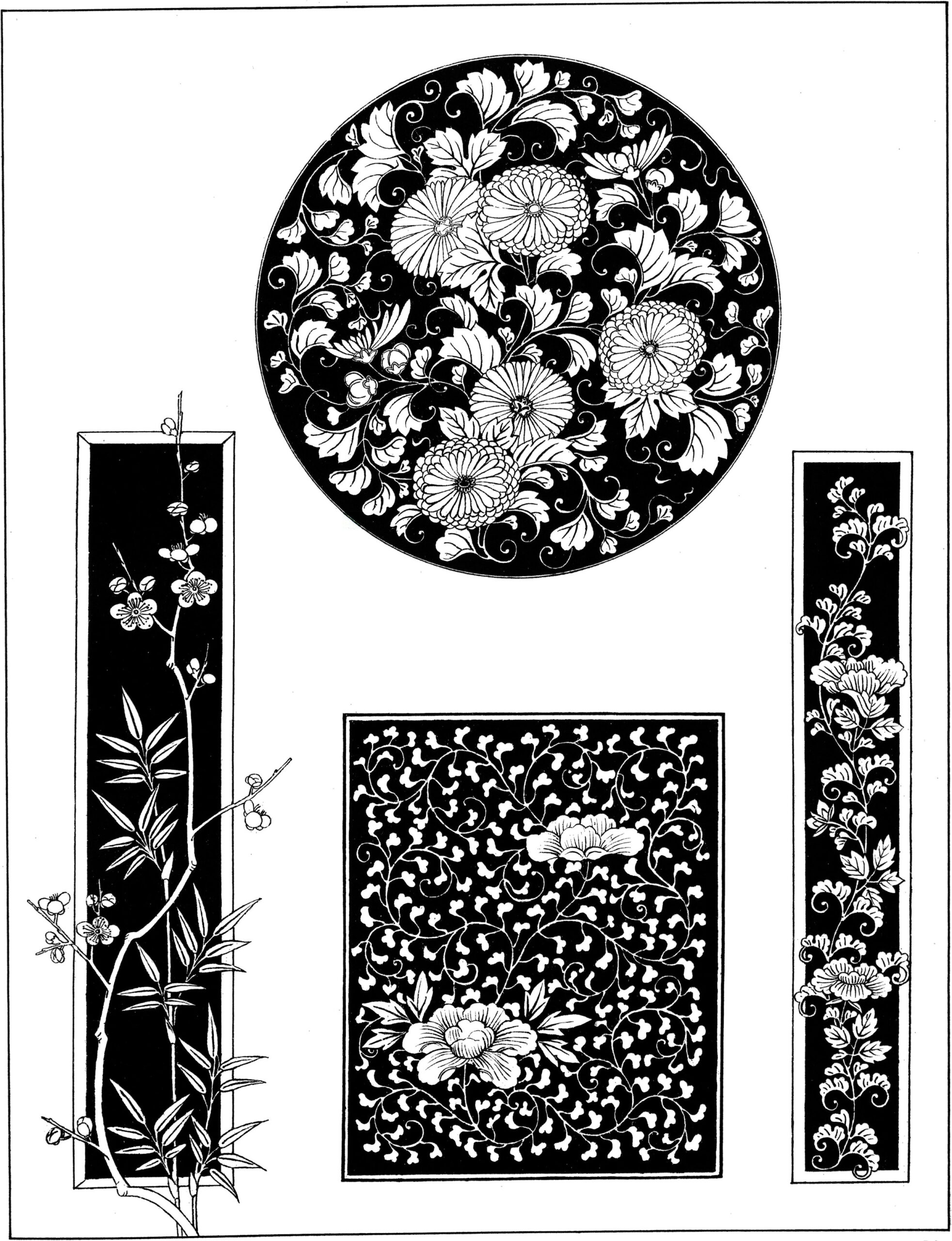

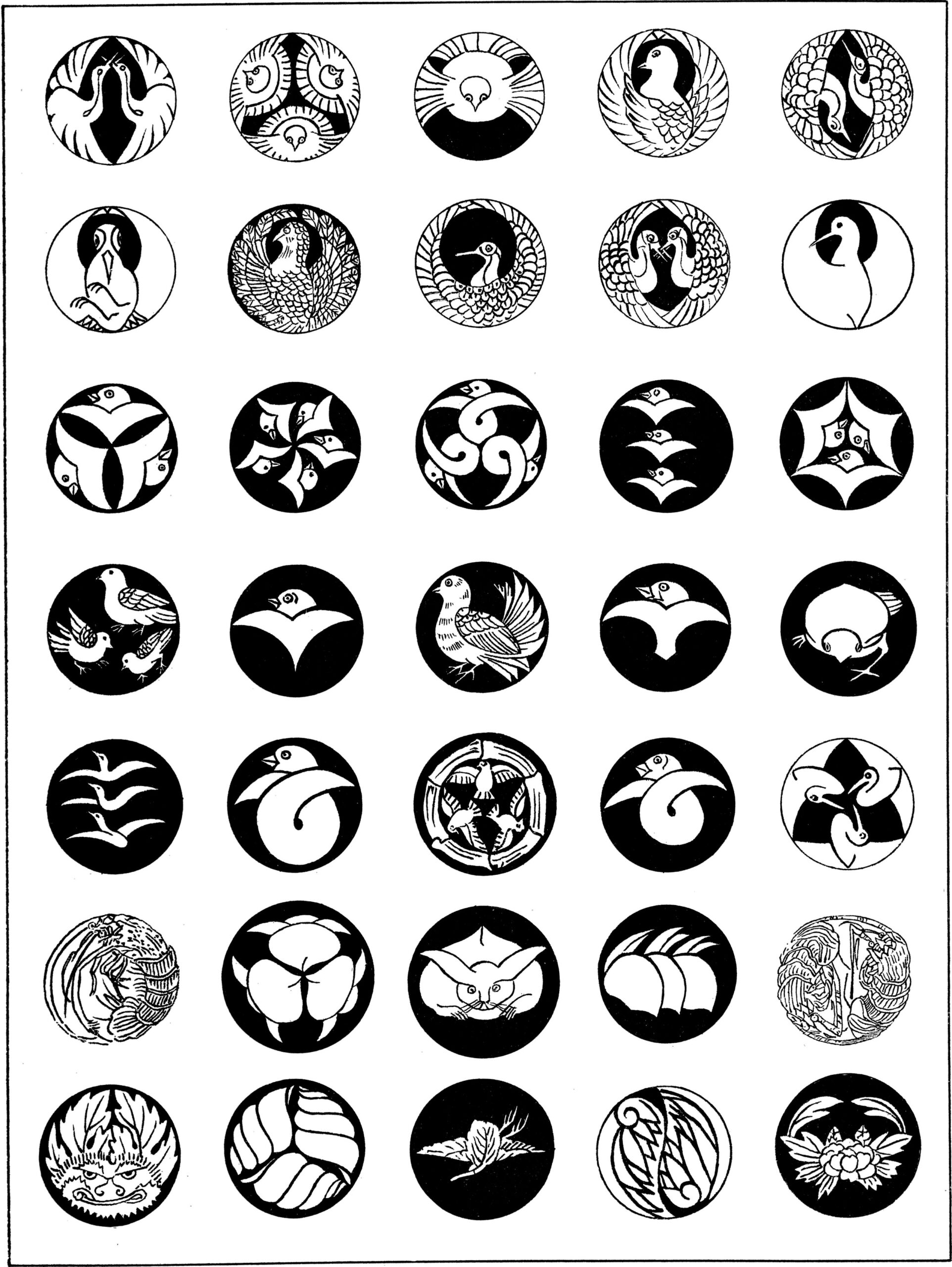

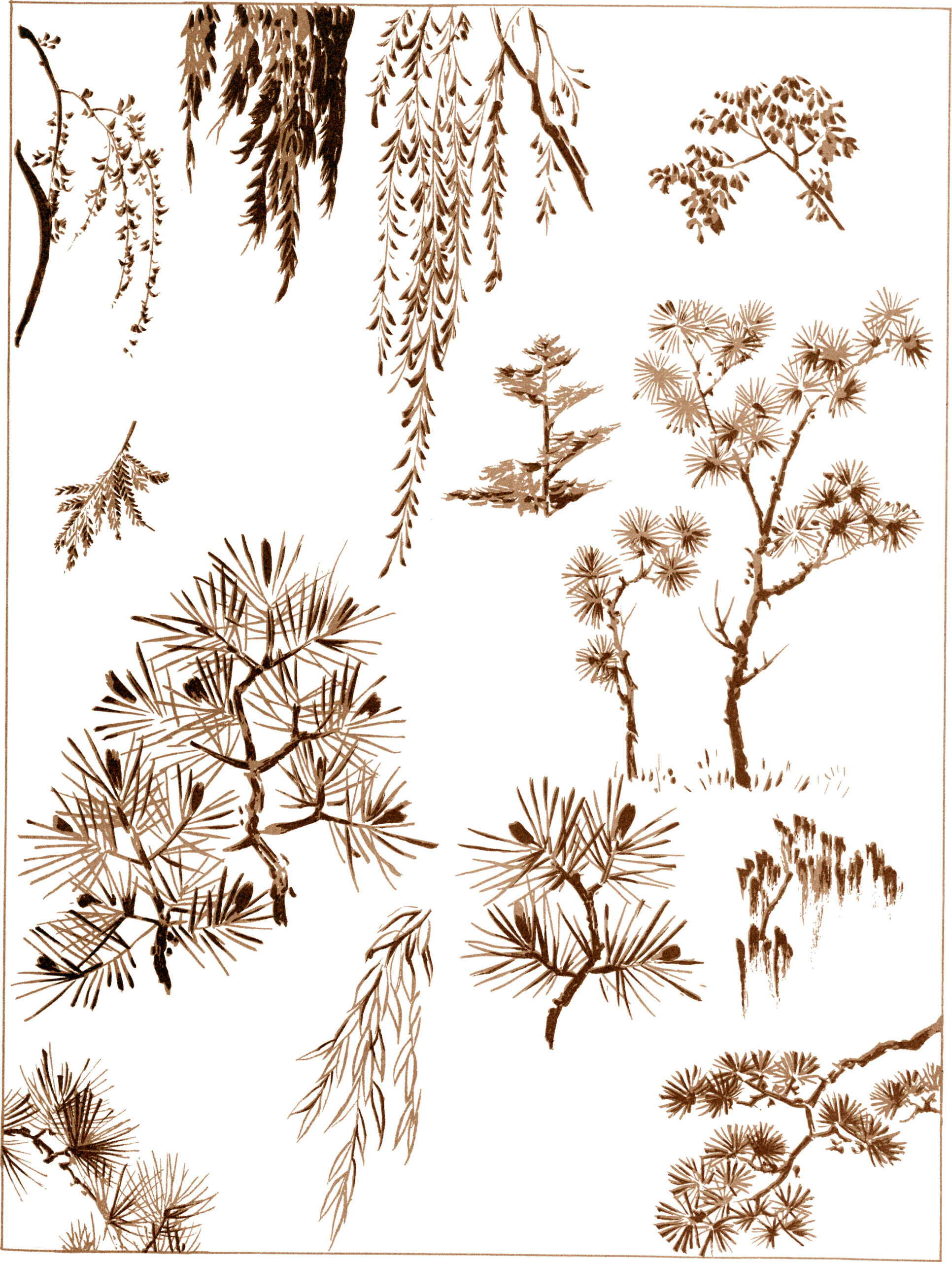

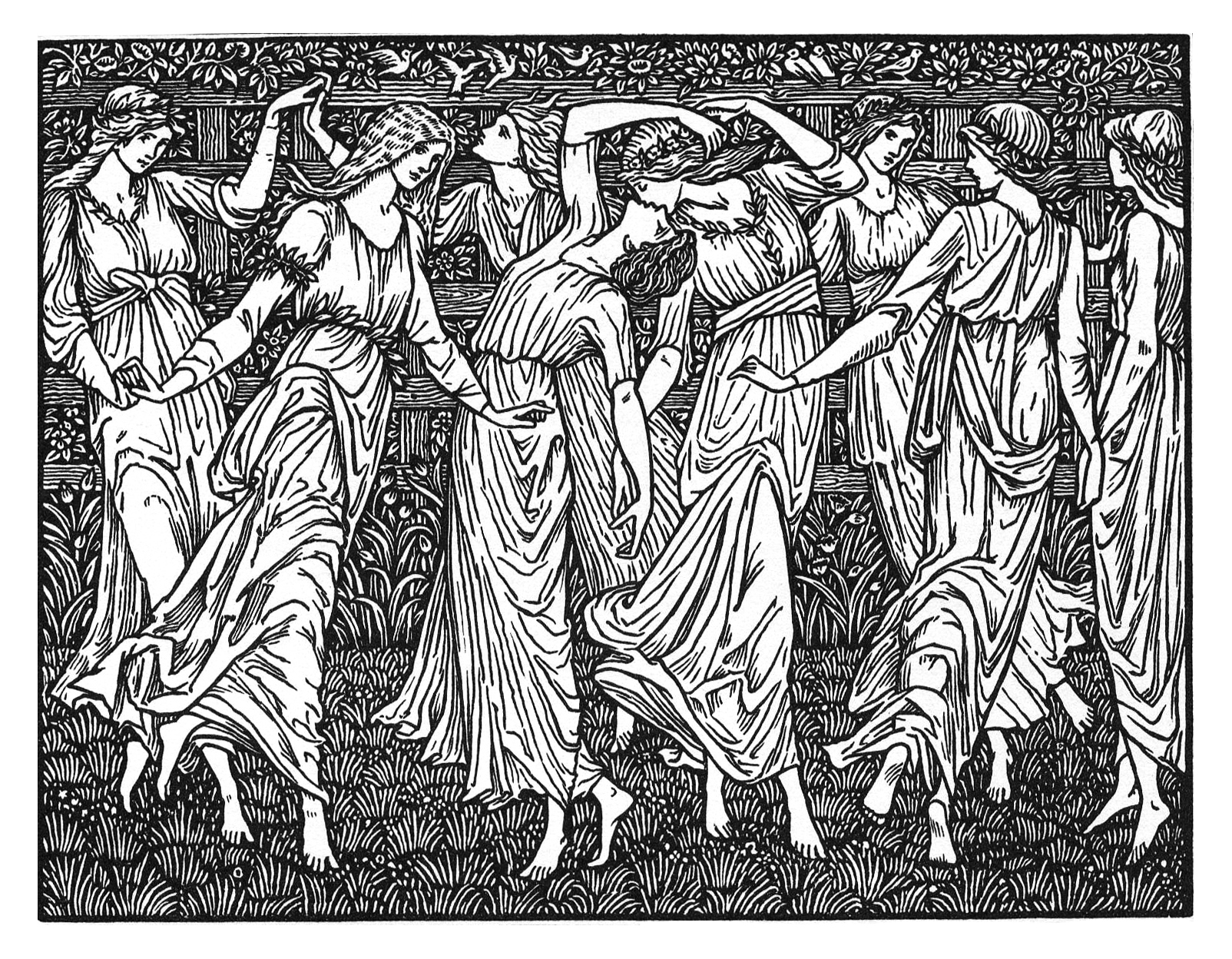

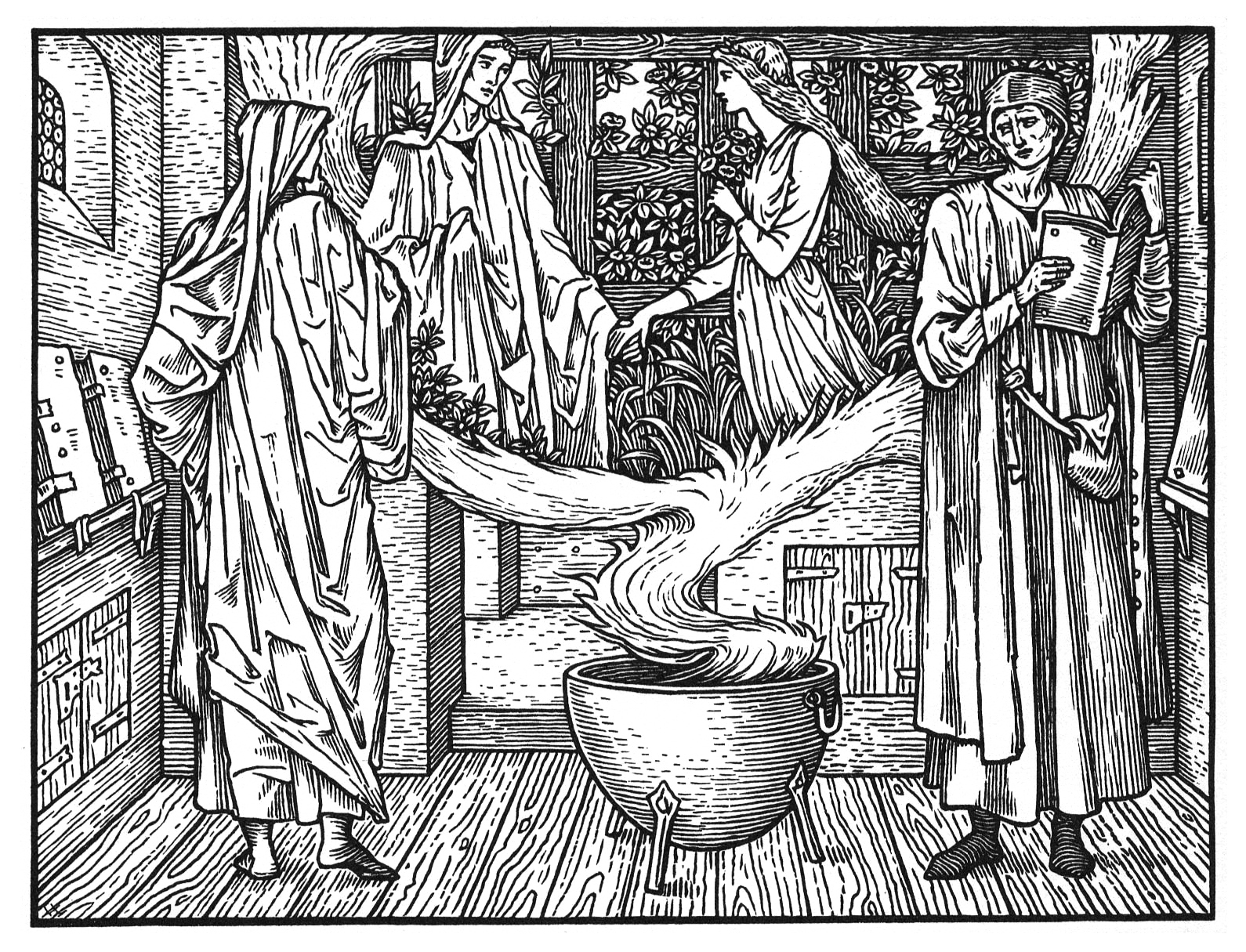

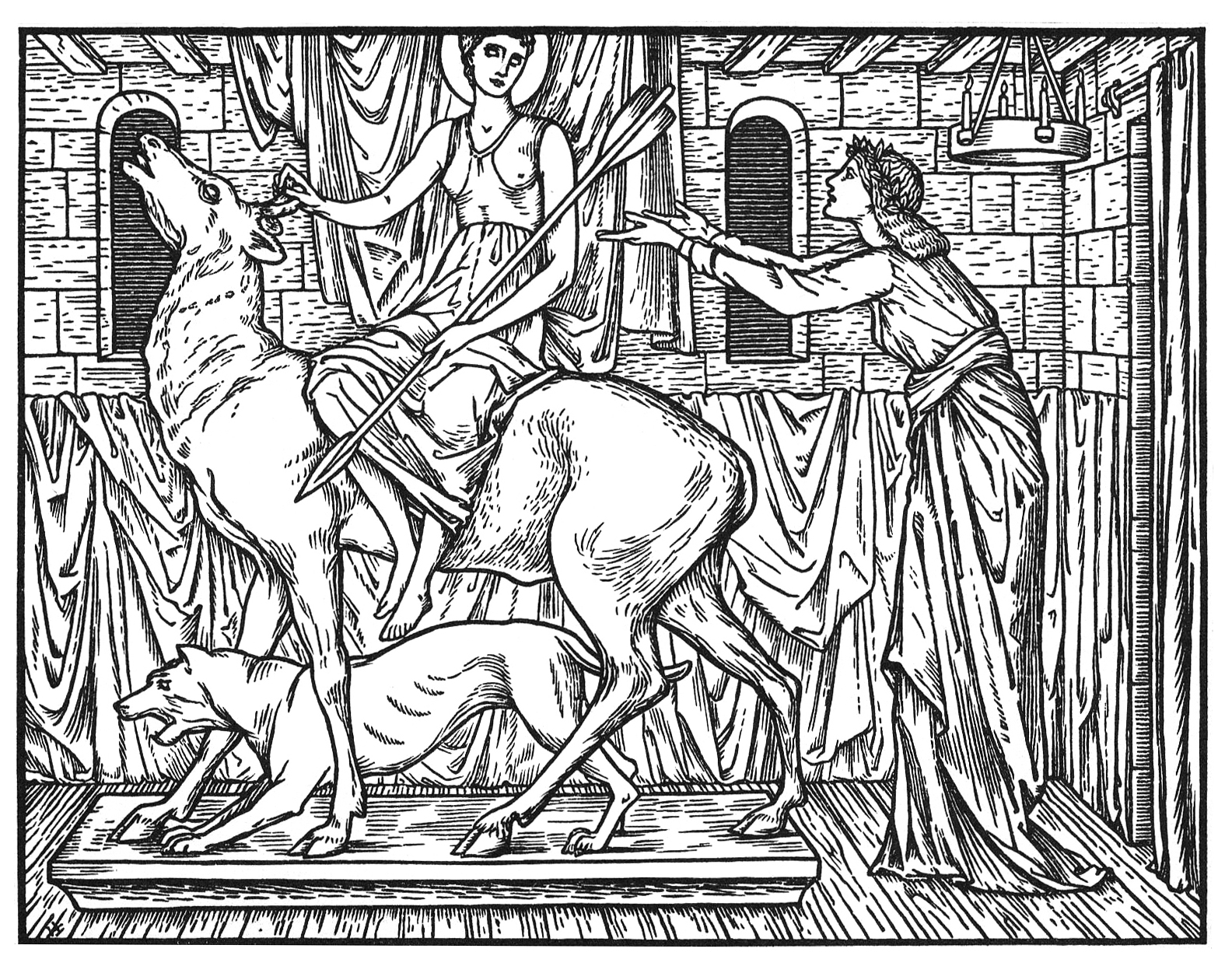

Published in 1896, the Kelmscott Chaucer, fully titled The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer now newly imprinted, “is the triumph of the press. Its 87 wood-cut illustrations are by Edward Burne-Jones, the celebrated Victorian painter, who was a life-long friend of Morris. The illustrations were engraved by William Harcourt Hooper and printed in black, with shoulder and side titles.”

You can view all these elements and more, digitized in detail and entirely downloadable, on Goodman’s site, organized into separate sections dedicated to its illustrations, full pages, borders, frames, and even its decorated words — the likes of which we seldom, if ever, see in the printed books of our own, infinitely higher-tech century. “The edition I have used for this project is a facsimile from the 1950s that has sat on my shelf for many years,” Goodman notes. Given how few copies of the Kelmscott Chaucer were originally produced, thirteen copies on vellum, and another 58 on pig’s skin, “any special collection’s library who are lucky enough to own an original copy are likely to be very reluctant to embark upon any form of digitization due to the significant risk of damage that the process could inflict upon the book.”

If you’d like a closer look at the genuine article, which is much larger than the digitization may let on, you can get one in the video just above, hosted by London rare book dealer Adam Douglas. “It’s obvious as soon as we open to the beginning how much care and attention has been lavished on this book,” he says, highlighting the “beautiful designs in the pre-Raphaelite manner,” the woodcut initials throughout (no two of which are alike), and the “wonderful proportions” that match the Golden Ratio. It takes a certain sophistication, or at least knowledge of the history of printing and book design, to fully appreciate the Kelmscott Chaucer. But thanks to Goodman, younger readers — even much younger readers — can enjoy it in coloring-book form.

Related content:

Download Free Coloring Books from Nearly 100 Museums & Libraries

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.