The skating scene that opens A Charlie Brown Christmas is such an evocative, archetypical winter vision, it’s likely to stir nostalgia even in those whose childhoods didn’t involve gliding across frozen ponds.

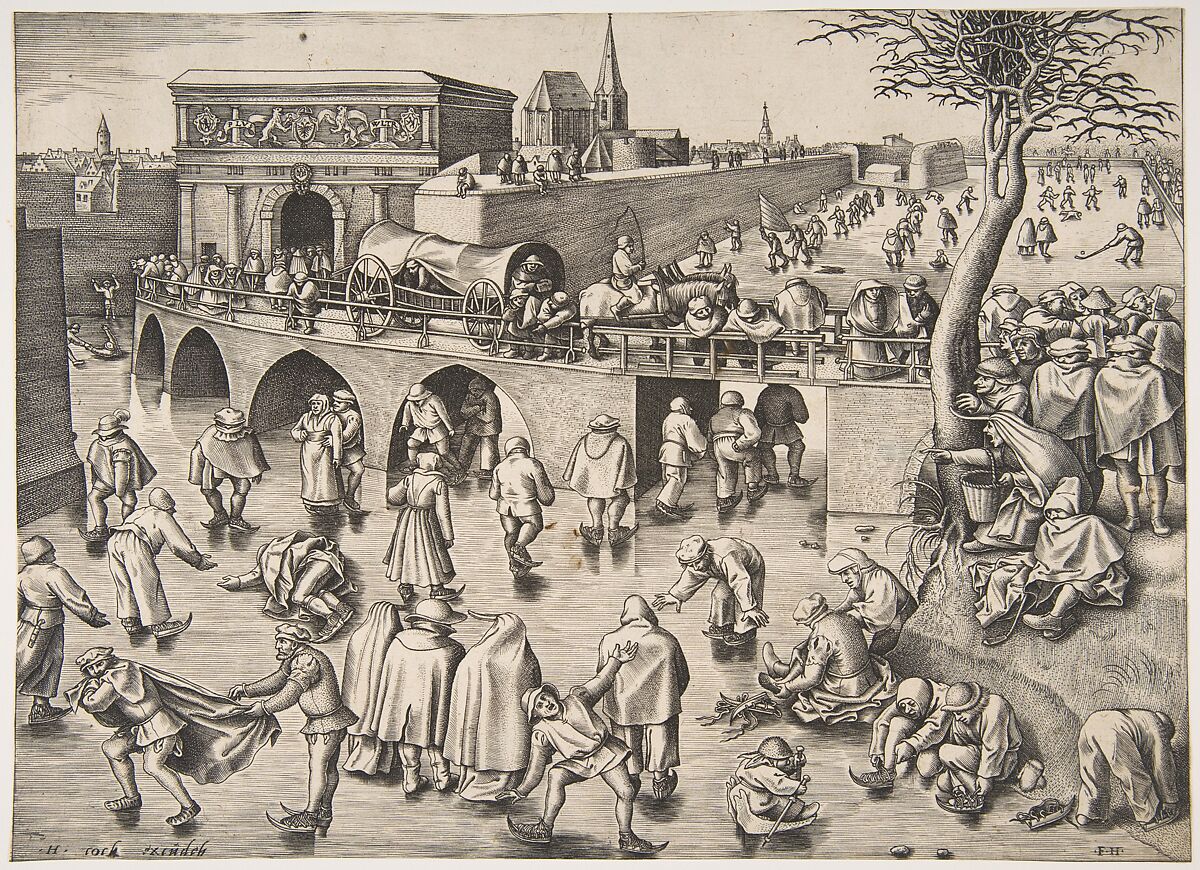

Pieter Bruegel the Elder created a similar scene in the 16th-century. His changed the course of Western art.

Prior to his 1558 Ice Skating before the Gate of Saint George, Antwerp, Western artists mostly stuck to VIP portraits, and religious and mythological subjects.

As the Nerdwriter, Evan Puschak, explains above, the rare exceptions to these themes were intended to reinforce some moral instruction, often via buffoonish depictions of regular people behaving badly.

The couple in Quentin Matsys’ The Money Changer and His Wife are far less grotesque than the central figure of his satirical portrait, The Ugly Duchess, but the symbolism and the wife’s keen focus on the coins her husband is counting point to a sort of spiritual ugliness, namely a preoccupation with material wealth.

Jan Sanders van Hemessen’s Loose Company and Pieter Aertsen’s The Egg Dance are both set in brothels, where debauchery is in ample evidence.

Bruegel painted some works in this vein too. The Fight Between Carnival and Lent pits pious churchgoers against a plump butcher riding a barrel, a guy with a pot on his head, and many more revelers acting the fool.

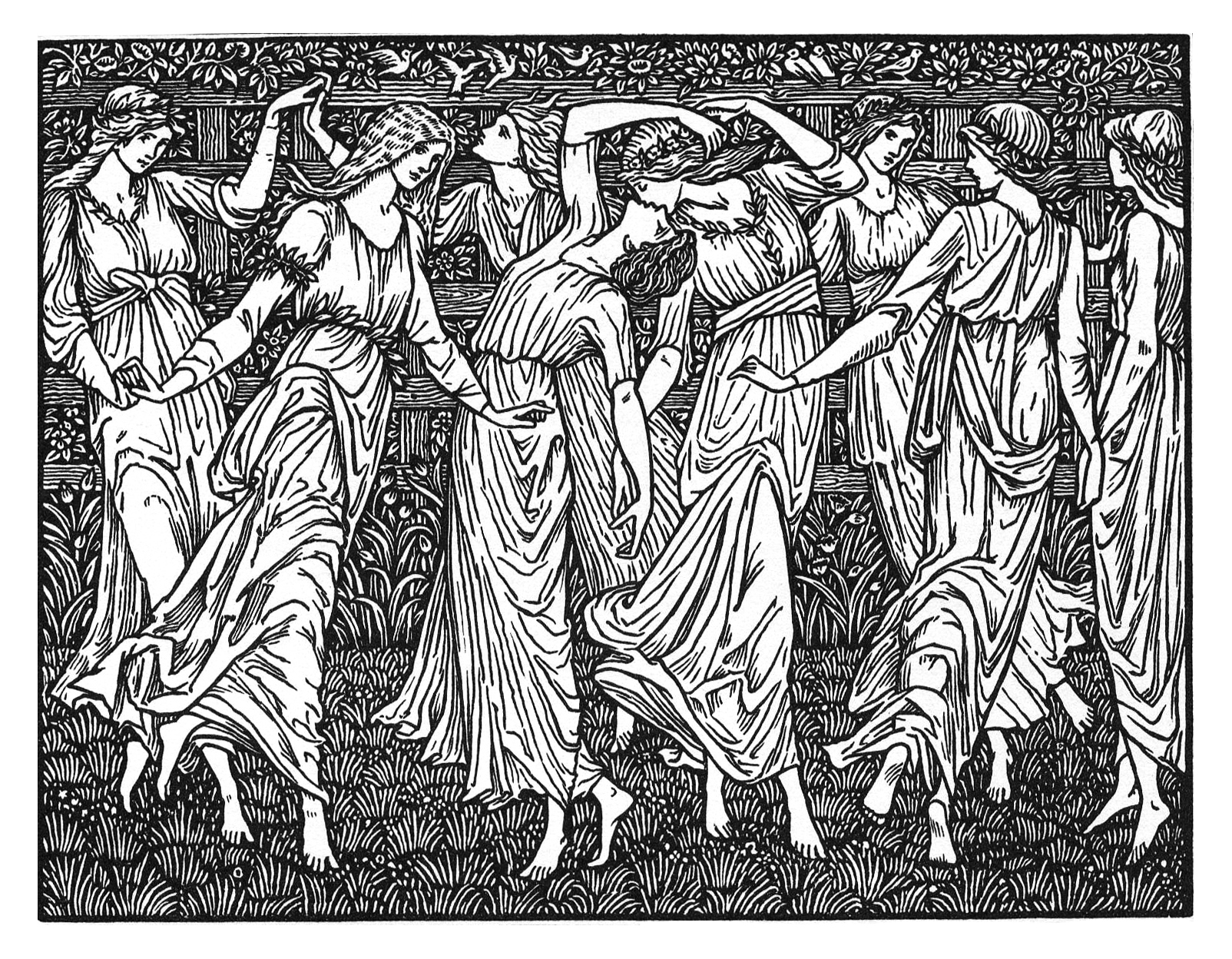

His skating scene, by contrast, passes no judgements. It’s just an observation of ordinary citizens amusing themselves outdoors during the ‘Little Ice Age’ that gripped Western Europe in the mid 16th century.

Adults bind runner-like blades to their feet with laces…

A small child uses poles to propel himself on a sled made from the mandible of a cow or horse…

A background figure plays with a hockey stick…

Less gifted skaters cut ungainly figures as they attempt to remain upright. (Pity the poor woman sprawled in the middle, whose skirts have flipped up to expose her bare heinie…)

Bruegel’s humanist portrayal of a crowd engaged in a recognizable, populist activity proved wildly popular with the growing merchant class. They might not have been able to afford an original painting, but prints of the engraving, published by the wonderfully named Hieronymus Cock, were well within their reach.

The everyday subject matter that so captivated them was made possible in part by the Protestant Reformation, which came to a head with the Iconoclastic Fury, eight years after “Peasant” Bruegel’s densely populated image appeared.

The image wins the approval of modern skating buffs too.

American field hockey pioneer Constance M.K. Applebee included it in her 20s era magazine, The Sportswoman. So did sportswriter Arthur R. Goodfellow in 1972’s Wonderful world of skates: Seventeen centuries of skating which prompted figure skating historian Ryan Stevens to quote a translated Old Flemish inscription on his blog:

Skating on ice outside the walls of Antwerp,

Some slide hither, others hence, all have onlookers everywhere;

One trips, another falls, some stand upright and chat.

This picture also tells one how we skate through our lives,

And glide along our paths; one like a fool, another like a wise;

On this perishable earth, brittler than ice.

Explore another of Pieter Bruegel’s teeming depictions of ordinary life with the Khan Academy/Smart History’s breakdown of 1567’s Peasant Wedding, below.

Related Content

The Stay At Home Museum: Your Private, Guided Tours of Rubens, Bruegel & Other Flemish Masters

What Makes Vermeer’s The Milkmaid a Masterpiece?: A Video Introduction

A Short Introduction to Caravaggio, the Master Of Light

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.