Equipped with smartphones that grow more powerful by the year, gamers on the go now have a seemingly unlimited variety of playing options. A decade ago they relied on handheld game consoles with their thousands of available game cartridges and later discs, whose reign began with Nintendo’s introduction of the original Game Boy (a device whose unwrapping on Christmas 1990 remains one of my most vivid childhood memories). But even before the Game Boy and its successors, there were standalone handheld proto-video-games, “LCD, VFD and LED-based machines that sold, often cheaply, at toy stores and booths over the decades.”

Those words come from Jason Scott at the Internet Archive, where you can now play a range of those handheld games again, emulated right here in your browser. “They range from notably simplistic efforts to truly complicated, many-buttoned affairs that are truly difficult to learn, much less master,” Scott writes.

“They are, of course, entertaining in themselves – these are attempts to put together inexpensive versions of video games of the time, or bringing new properties wholecloth into existence.” They also “represent the difficulty ahead for many aspects of digital entertainment, and as such are worth experiencing and understanding for that reason alone.”

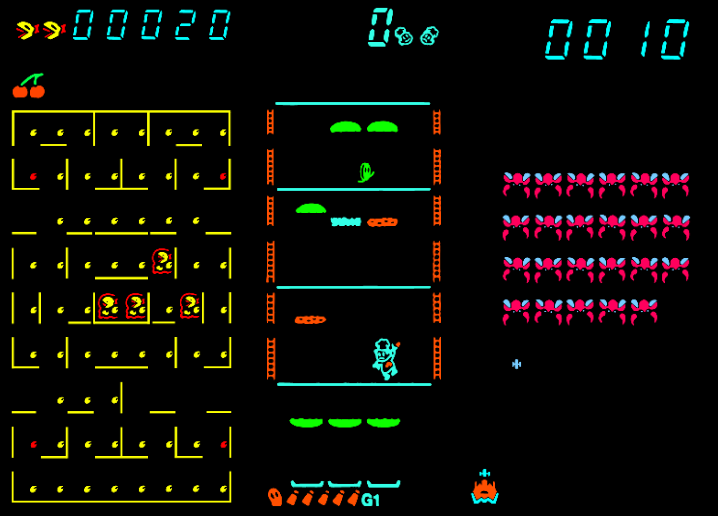

What kind of games came in this form? The Internet Archive’s current offerings include vague approximations of 70s and 80s arcade hits like Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, and Q*Bert; even vaguer approximations of such major motion pictures of the day as Tron, Robocop 2 (as well as Robocop 3), and Apollo 13; and sports titles like World Championship Baseball, NFL Football, and Blades of Steel. You’ll even find popular oddities like Bandai’s Tamagotchi, the original virtual pet, along with less popular oddities like MC Hammer, a dual-directional-padded simulation of a dance battle with the auteur of “U Can’t Touch This.”

So as you play, spare a thought for the developers of these handheld games, not just because of the dire intellectual property they often had to work with, but the severe technological restrictions they invariably had to work under. “This sort of Herculean effort to squeeze a major arcade machine into a handful of circuits and a beeping, booping shell of what it once was is an ongoing situation,” writes Scott. “Where once it was trying to make arcade machines work both on home consoles like the 2600 and Colecovision, so it was also the case of these plastic toy games. Work of this sort continues, as mobile games take charge and developers often work to bring huge immersive experiences to where a phone hits all the same notes.” And the day will certainly come when even the most impressive games we play now, handheld or otherwise, will seem just as hilariously simplistic.

Enter the handheld video collection here. And find more classic video games in the Relateds below.

Related Content:

Play “Space War!,” One of the Earliest Video Games, on Your Computer (1962)

Pong, 1969: A Milestone in Video Game History

The Internet Arcade Lets You Play 900 Vintage Video Games in Your Web Browser (Free)

Free: Play 2,400 Vintage Computer Games in Your Web Browser

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.