Yesterday a friend and I were standing on a New York City sidewalk, waiting for the light, when Stayin’ Alive began issuing at top volume from a nearby car.

Pavlovian conditioning kicked in immediately. We’d been singing along with the Bee Gees for nearly a minute before realizing that neither of us knew the lyrics. Like, at all.

Italian actor and musician Adriano Celentano’s cult classic, Prisencolinensinainciusol, inspires a similar response.

The difference being that should I ever need to prep for karaoke, Stayin’ Alive’s lyrics are widely available online, whereas Prisencolinensinainciusol’s lyrics are kind of anyone’s guess…nonsense in any language.

Celentano improvised this gibberish in 1972 in an attempt to recreate how American rock and roll lyrics sound like to non-English-speaking Italian fans like himself.

As he told NPR’s All Things Considered through a translator during a 2012 interview:

Ever since I started singing, I was very influenced by American music and everything Americans did. So at a certain point, because I like American slang — which, for a singer, is much easier to sing than Italian — I thought that I would write a song which would only have as its theme the inability to communicate…I sang it with an angry tone because the theme was important. It was an anger born out of resignation. I brought to light the fact that people don’t communicate.

And yet, his 1974 appearance in the above sketch on the Italian variety series Formula Due spurs strangers to make stabs at communication by sharing their best guess transcriptions of Prisencolinensinainciusol’s lyrics in YouTube comments, 51 years after the song’s original release.

A sampling, anchored by the chorus’ iconic and unmistakeable “all right:”

@glassjester:

My eyes lie, senseless.

I guess I’m throwing pizza.

Eyes.

And the cold wind sailor,

freezing cold and icy in Tucson

Alright.

@emanueletardino8545:

My eyes are way so sensitive

And it gets so cold, it’s freezing

Ice

You’re the cold, main, the same one

Please let’s call ’em ‘n’ dance with my shoes off

All right

@sexydudeuk2172

My eyes smile senseless but it doesn’t go with diesel all right.

@leviathan3187:

I don’t know why but I want a maid to say I want pair of ice blue shoes with eyes…awight.

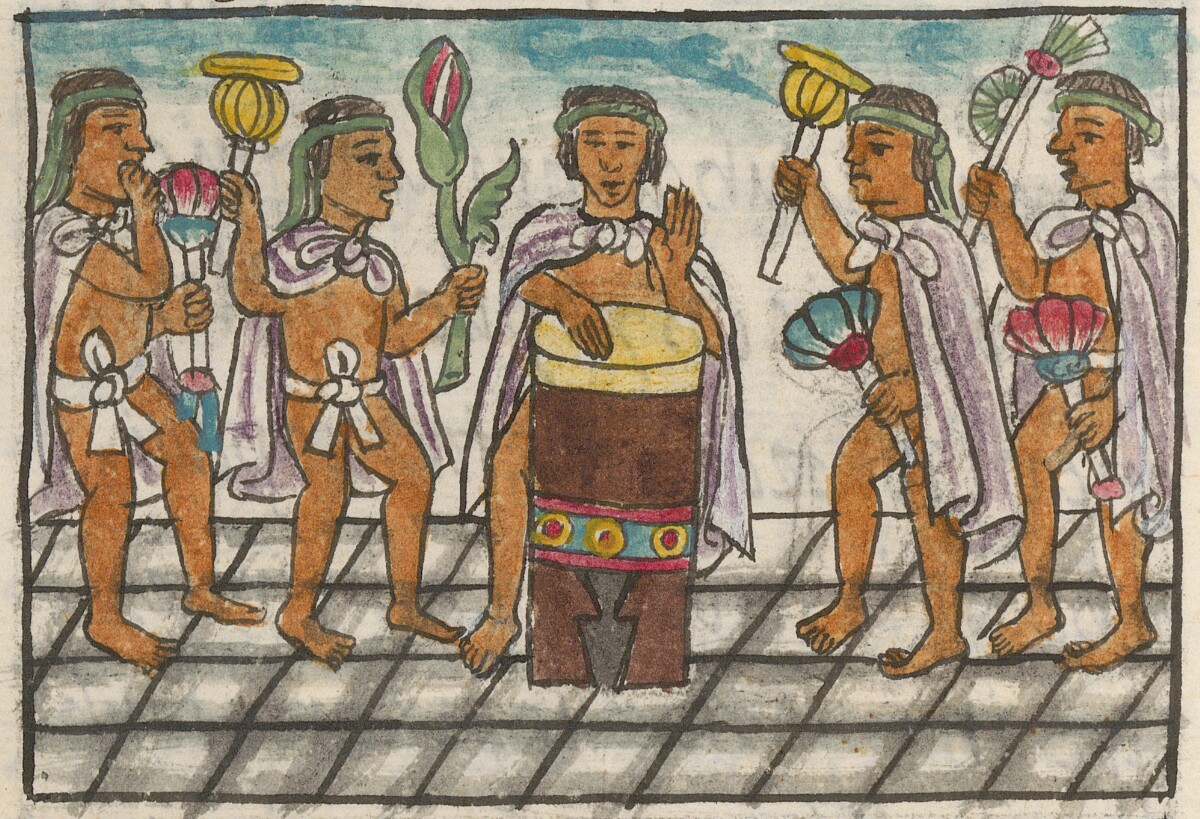

Prisencolinensinainciusol’s looping, throbbing beat is wildly catchy and imminently danceable, as evidenced by Celentano’s performance on Formula Due and that of the black clad dancers backing him up during an appearance on Milleluci, another mid-70s Italian variety show, below.

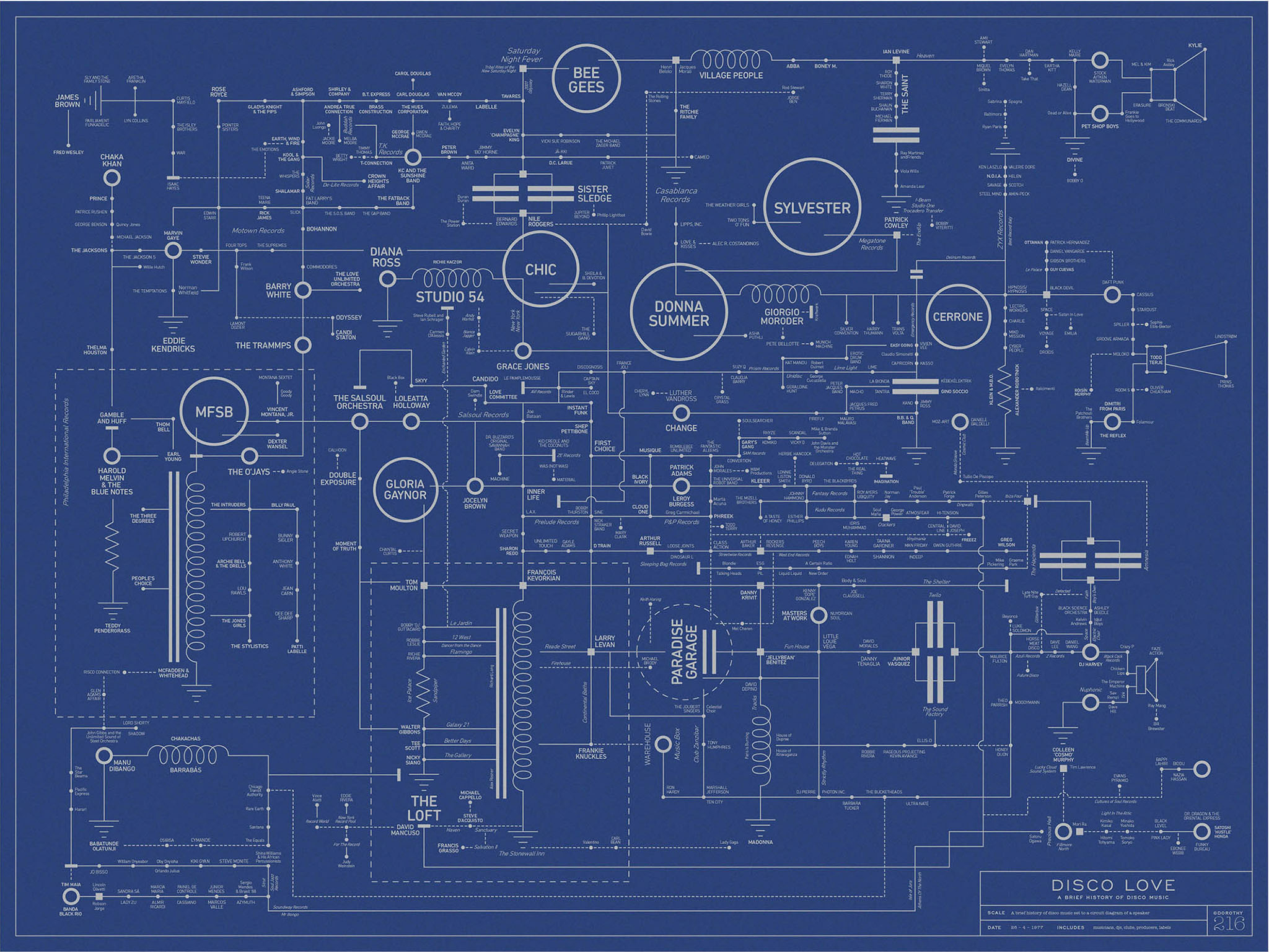

The attention generated by these variety show segments — both lip synched — sent Prisencolinensinainciusol up the charts in Italy, Belgium, Germany, France, the Netherlands, the UK, and even the United States.

Its mix of disco, hip hop and funk has proved surprisingly durable, inspiring remixes and covers, including the one that served as philosopher Slavoj Žižek’s Eurovision Song Contest entry.

Prisencolinensinainciusol has netted a whole new generation of fans by cropping up on Ted Lasso, Fargo, a commercial for spiced rum, and seemingly innumerable TikToks.

We’ll probably never get a firm grasp on the lyrics, despite Italian television host Paolo Bonolis’ puckish 2005 attempt to goad befuddled native English speaker Will Smith into deciphering them.

No matter.

Celentano’s supremely confident delivery of those indelible nonsense syllables is what counts, according to a YouTube viewer from Slovenia with fond memories of playing in a rock band as a teen in the 1960’s:

This is exactly how we non-English-speakers sung the then hit songs. You learned some beginning parts of lyrics so that the audience recognized the song. They heard it at Radio Luxembourg. From here on it was exactly the same style — outside the chorus of course. Adriano Celentano was always been a legend for us back in Slovenia.

h/t Erik B.

Related Content

Hear All of Finnegans Wake Read Aloud: A 35 Hour Reading

Watch La Linea, the Popular 1970s Italian Animations Drawn with a Single Line

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.