If you made it big in seventeenth-century Bavaria, you showed it by creating a garden with all the plants in the known world. That’s what Johann Konrad von Gemmingen, Prince-Bishop of Eichstätt did, anyway, and he wasn’t about to let his botanical wonderland die with him. To that end, he engaged a specialist by the name of Basilius Besler to document the whole thing, and with a lavishness never before seen in books in its category.

The medieval and Renaissance world had its “herbals” (as previously featured here on Open Culture), many of which tended toward the utilitarian, focusing on the culinary or medical properties of plants; Hortus Eystettensis would take the form at once to new artistic and scientific heights.

When the book came out in 1613, after sixteen years of research and production, von Gemmingen was already dead. But it proved successful enough as a product that Besler made sufficient money to set himself up with a house in a fashionable part of Nuremberg for the price of just five copies — five copies of the extravagant (and extravagantly expensive) hand-colored edition, at least.

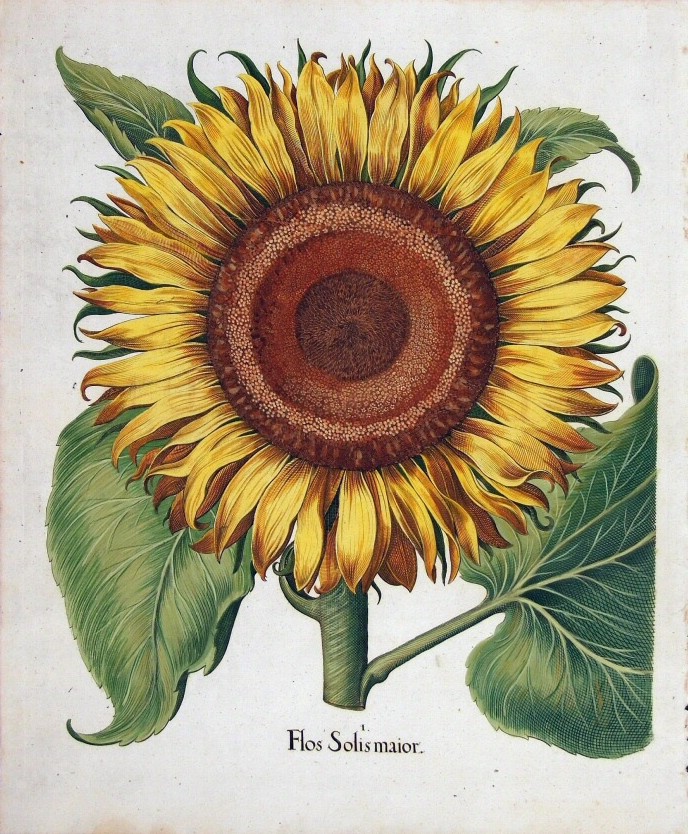

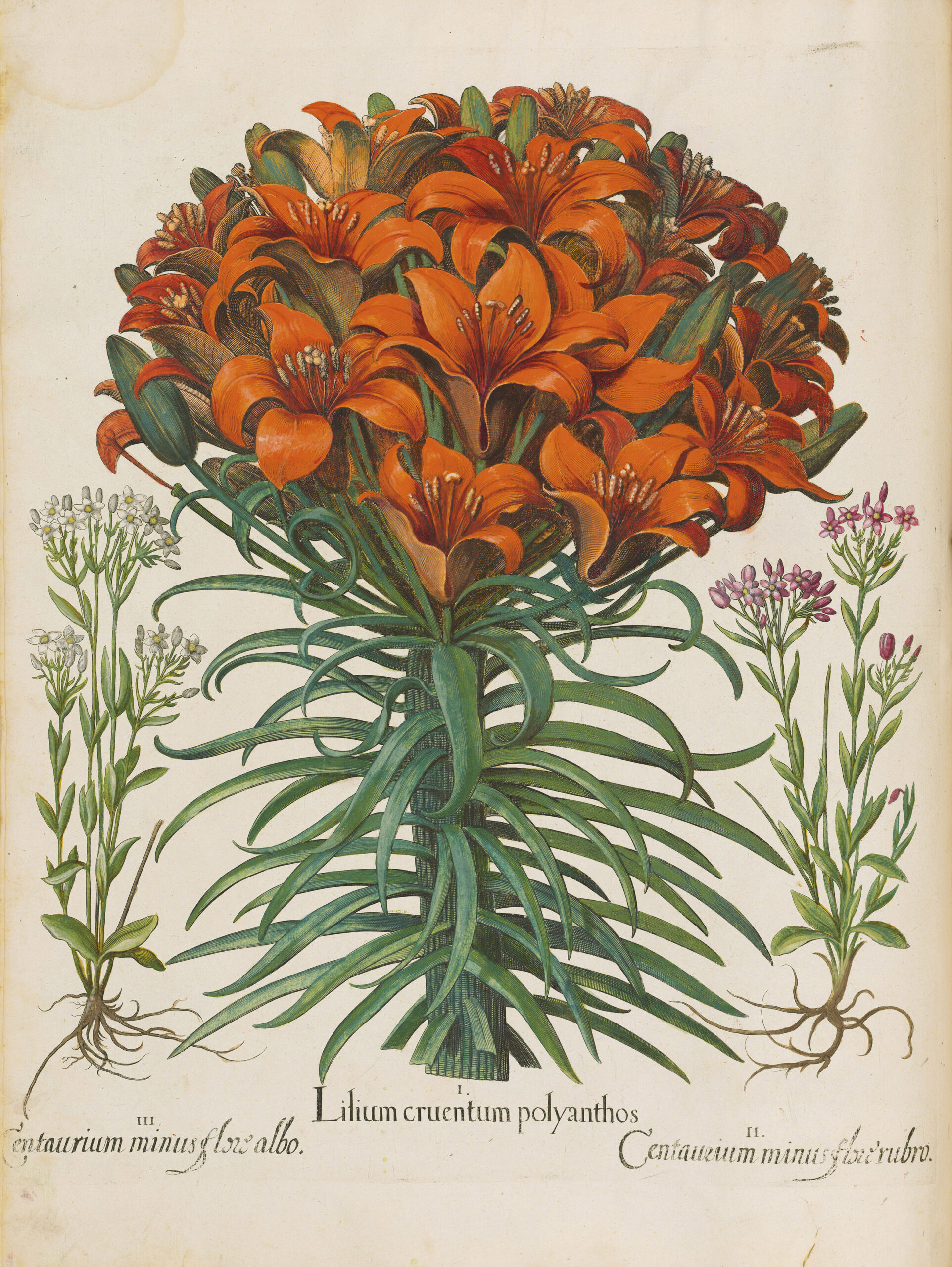

Hortus Eystettensis “changed botanical art almost overnight,” writes David Marsh in a detailed blog post on the book’s creation and legacy at The Gardens Trust. “Now, suddenly plants were being portrayed as beautiful objects in their own right,” with depictions that could attain life size, all categorized in a systematic manner anticipating classification systems to come. Marsh sees the project as exemplifying a couple major cultural ideas of its time: one was “the collector’s cabinet of curiosities or wunderkammer, which helped reveal a gentleman’s interest and knowledge of the world around him.” Another was the concept of the perfect garden, which “should, if at all possible, represent Eden and contain as wide a range of plants and other features as possible.”

This level of ambition has always had its costs, to the consumer as well as the producer: Marsh notes that a 2006 replica of Hortus Eystettensis had a price tag of $10,000, though a more affordable edition has since been made available from Taschen, the major publisher most likely to understand Besler’s uncompromising aesthetic sensibility in the craft of books. But you can also read it for free online at an edition digitized by Teylers Museum in the Netherlands, which, in a sense, brings von Gemmingen’s project full-circle: he sought to encompass the whole world in his garden, and now his garden — in Besler’s richly detailed rendering — is open to the whole world.

Related content:

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.