Mathematics, astronomy, history, law, literature, architecture: in these fields and others, the Muslim world came up with major innovations before any other civilization did. This Islamic cultural and intellectual flowering lasted from the 11th through the 19th century, and many of the texts the period left as its legacy have gone mostly unresearched. So say the creators of Manuscripts of the Muslim World, a project of Columbia University, the Free Library of Philadelphia, the University of Pennsylvania, Bryn Mawr College, and Haverford College aimed at creating an online archive of “more than 500 manuscripts and 827 paintings from the Islamicate world broadly construed.”

As UPenn Libraries Senior Curator of Special Collections Mitch Fraas tells Hyperallergic’s Sarah Rose Sharp, “The aim of this project was to find and digitize all the Islamicate manuscripts in Philadelphia collections and along the way we partnered with Columbia on a grant to take a multi-city approach.”

To the sources of its manuscripts it also takes a multi-culture approach, including “texts related to Christianity (Coptic and Syriac mss. galore), Hinduism (epics translated into Persian in Mughal India), science, technology, music, etc. but which were produced in the historic Muslim world.” There are also texts, he adds, “in Persian, Arabic, and Turkish of course but also in Coptic, Tamazight, Avestan, etc.”

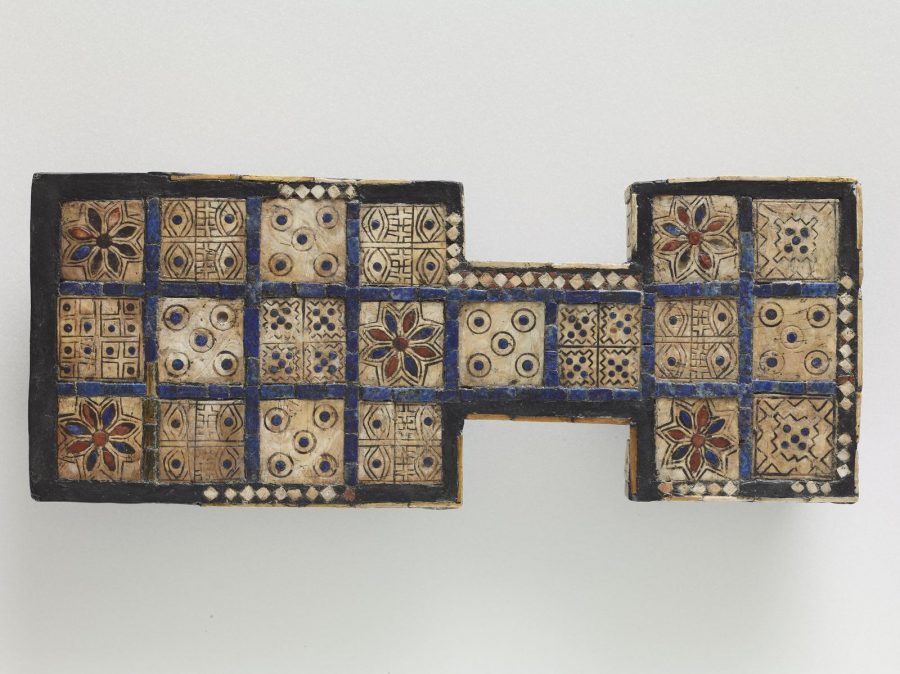

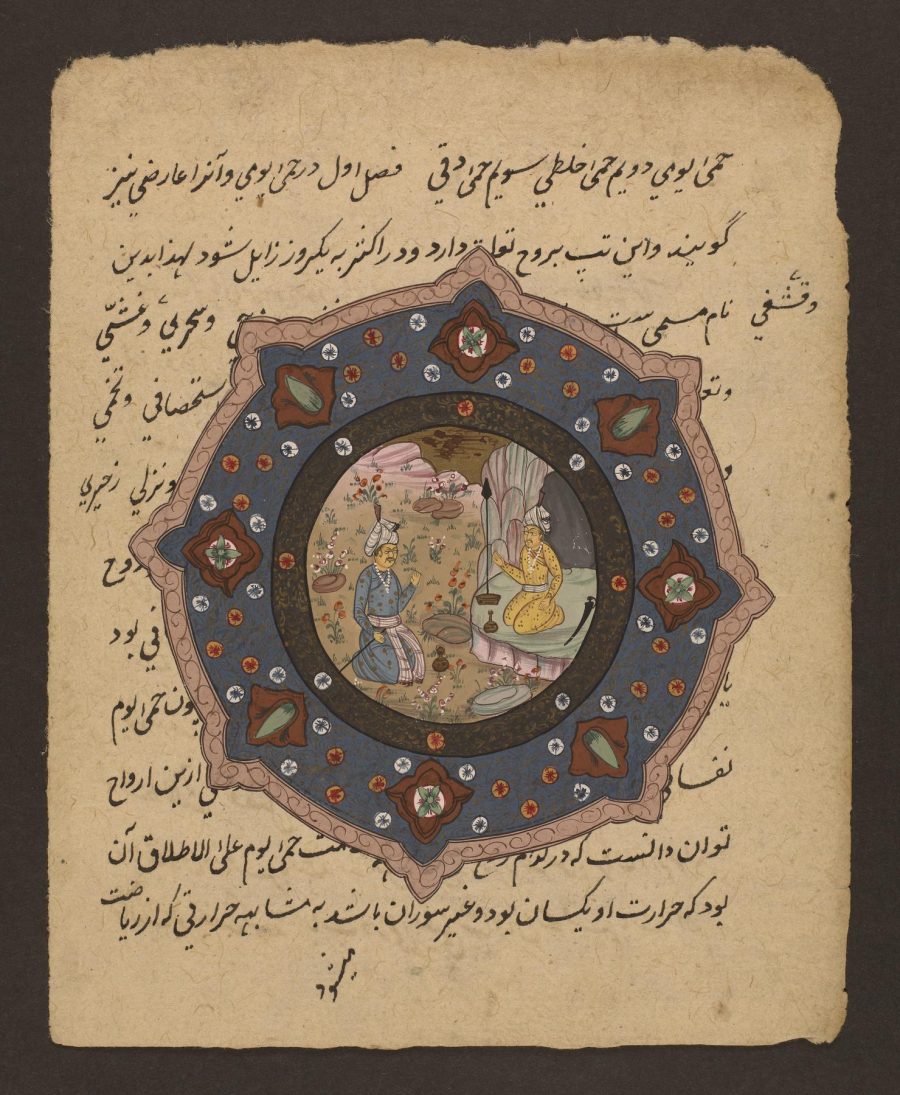

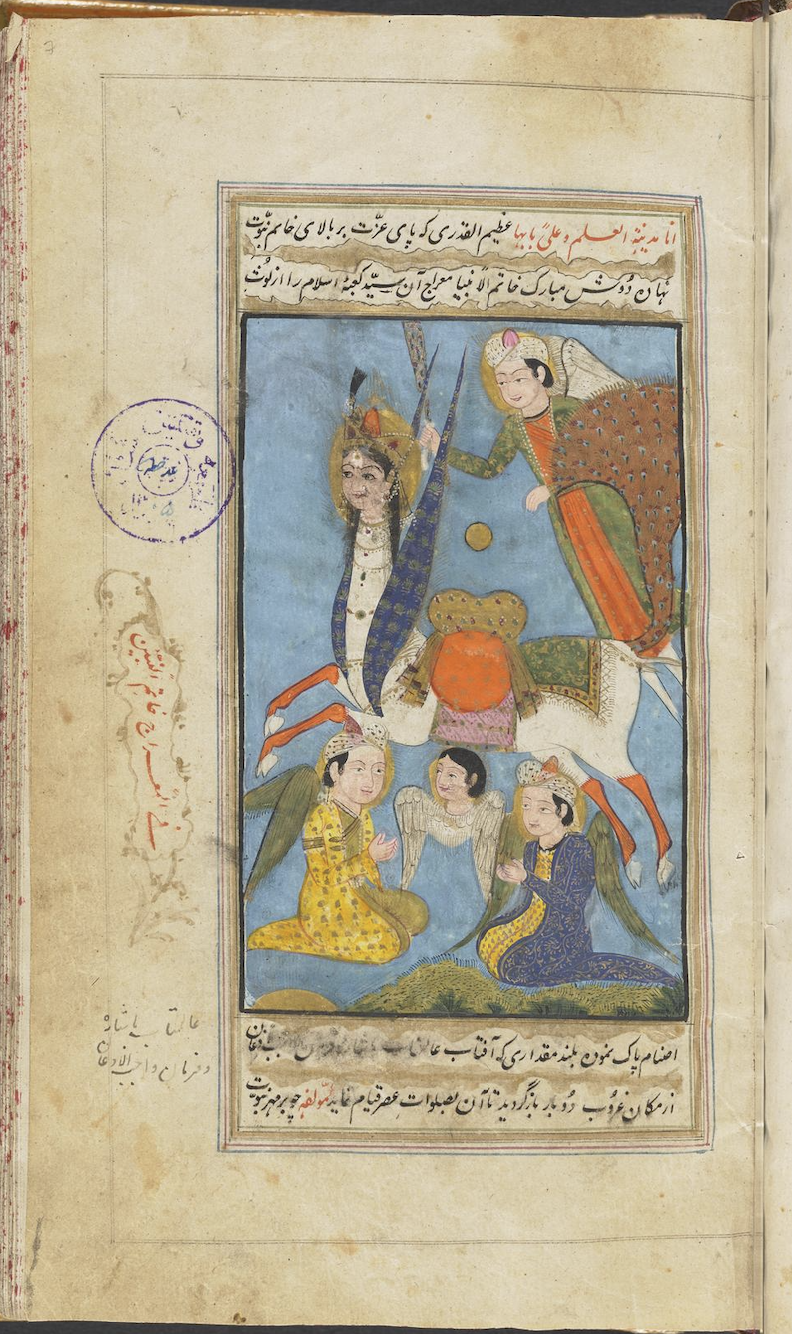

If you can read those languages, Manuscripts of the Muslim World obviously amounts to a gold mine. (You may also find something of interest in the digital archives of 700 years of Persian manuscripts and 10,000 books in Arabic we’ve previously featured here on Open Culture.) But even if you don’t, you’ll find in the collection marvels of book design that will appeal to anyone with an appreciation of the lush aesthetics, both abstract and figurative, of these places and these times. Some of them aren’t even as old as they may seem: take the manuscript at the top of the post, “overpainted in the 20th century to mimic Mughal style.” Or the one below that, whose colophon “says the copy was completed in 1121 A.H. (1709 or 1710 CE),” which “does not make sense given the author likely lived in the 19th century.”

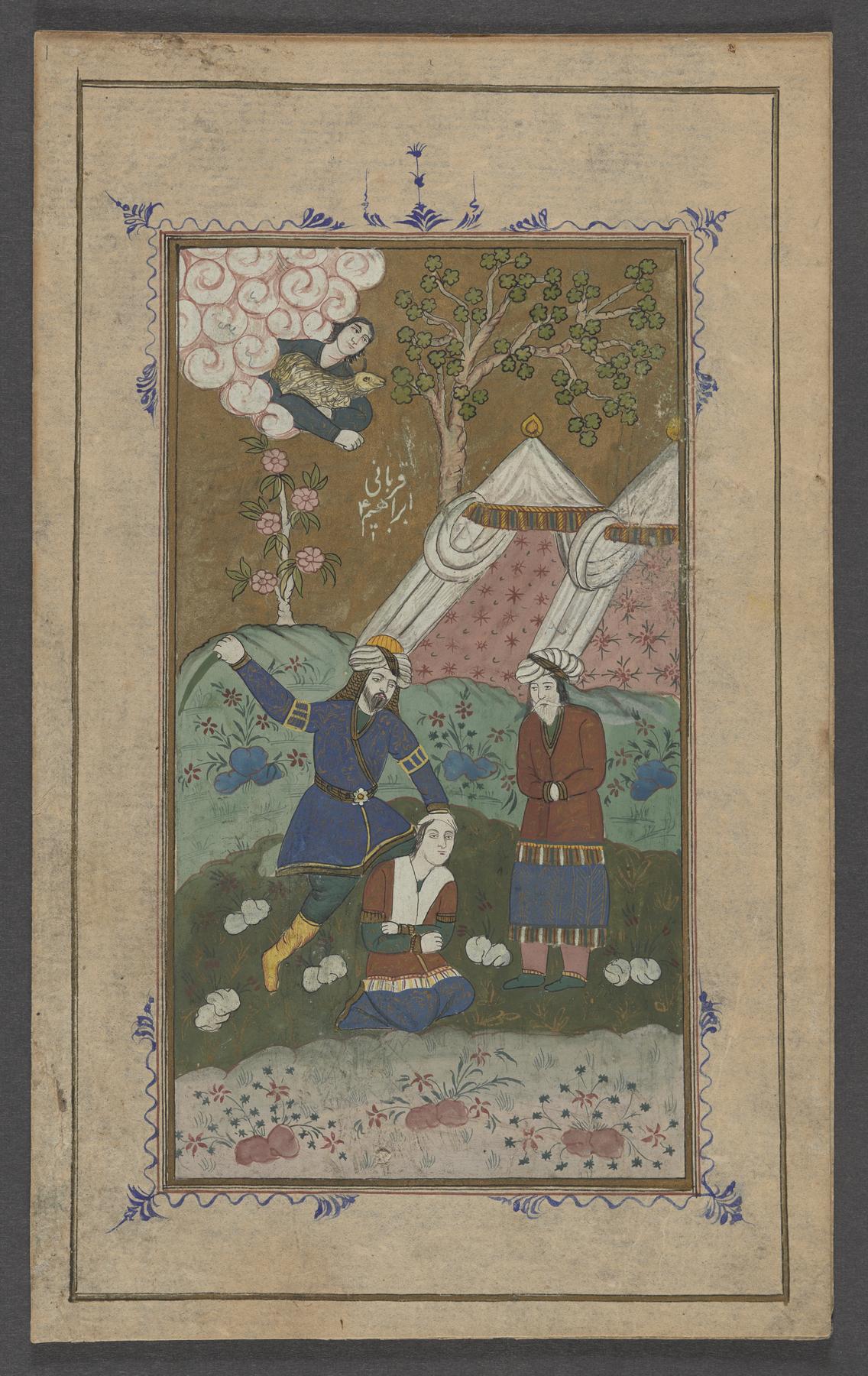

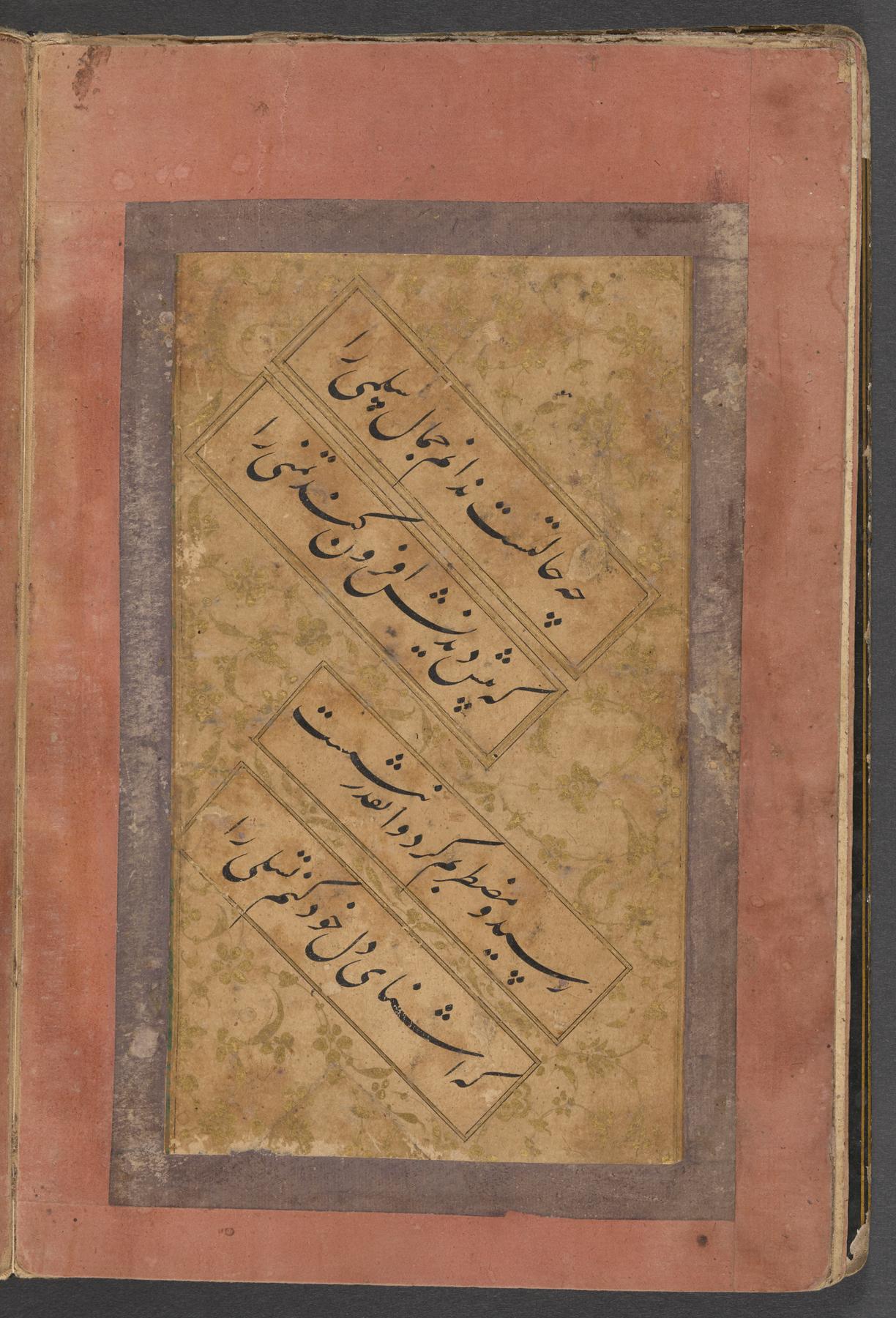

The other pages here come from a set of “illustrations from Qur’ānic stories” (this one depicting “Abraham sacrificing his son”) and a “Persian calligraphy and illustration album.” You’ll find much more in Manuscripts of the Muslim World, hosted on OPENN, the University of Pennsylvania’s online repository of “high-resolution archival images of manuscripts” accompanied by “machine-readable TEI P5 descriptions and technical metadata,” all released into the public domain or under Creative Commons licenses. Though each manuscript’s entry comes with basic notes, the collection is, in the main, not yet a thoroughly studied one. If you have an interest in the Islamic world at its peak of cultural and intellectual influence so far, you may just find your next big research subject here — or at the very least, material for a few hours’ admiration. Enter the collection.

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

The Complex Geometry of Islamic Art & Design: A Short Introduction

How Arabic Translators Helped Preserve Greek Philosophy … and the Classical Tradition

700 Years of Persian Manuscripts Now Digitized and Available Online

Download 10,000+ Books in Arabic, All Completely Free, Digitized and Put Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.