Funeral rites, burials, and other rituals are held near-universally sacred, not only due to religious and cultural beliefs about death: We preserve our connection to our ancestors through the records of their births and deaths. For many Black Americans in the U.S. south, grief and loss have been compounded by centuries of violence and tragedy, but funerals have still tended to be “celebrations of life” rather than mournful events, says Derek Mosley, archivist at the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.” African American “funeral programs tend to reflect that,” and therefore offer a wealth of information for historians and genealogists as well as family members.

Mosley is a contributor to a new digital archive that “currently boasts more than 11,500 digitized pages and is expected to grow as more programs are contributed.” These historical documents date from between 1886 to 2019, though “most of the programs are from services during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries,” notes the Digital Library of Georgia, who houses the collection. “A majority of the programs are from churches in the Atlanta, Georgia area, with a few programs from other states such as South Carolina, Tennessee, Florida, Michigan, New Jersey, and New York, among others.”

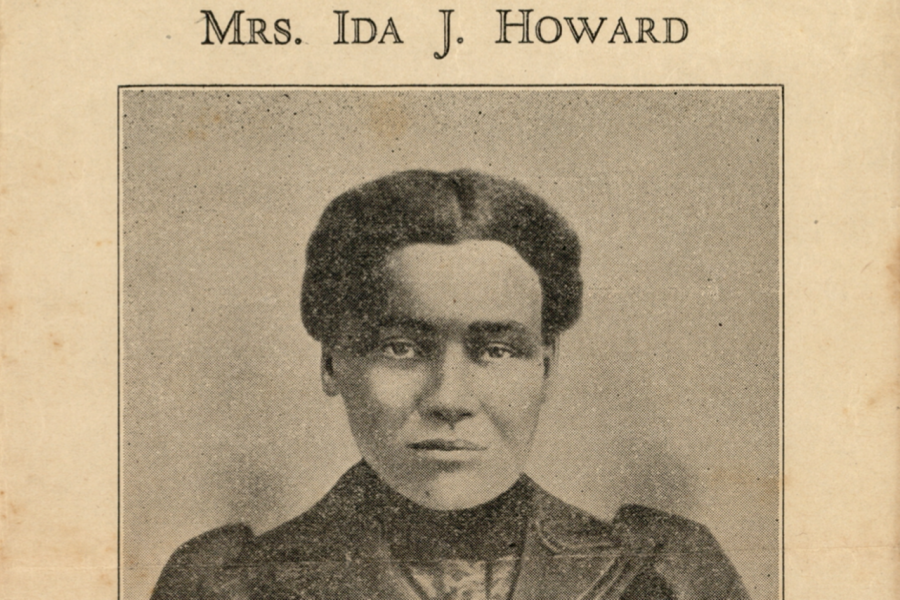

The archive offers an incredible resource for people looking for information about relatives. For researchers “these documents also represent a gold mine of archival information,” Nora McGreevy writes at Smithsonian, including “birth and death dates, photos, lists of relatives, nicknames, maiden names, residences, church names, and other clues that can help reveal the stories of the deceased.”

In many cases, those stories were lost when Jim Crow, poverty, and redevelopment displaced families and erased burial sites. The collection, says Mosley, offers “a public space for legacy.”

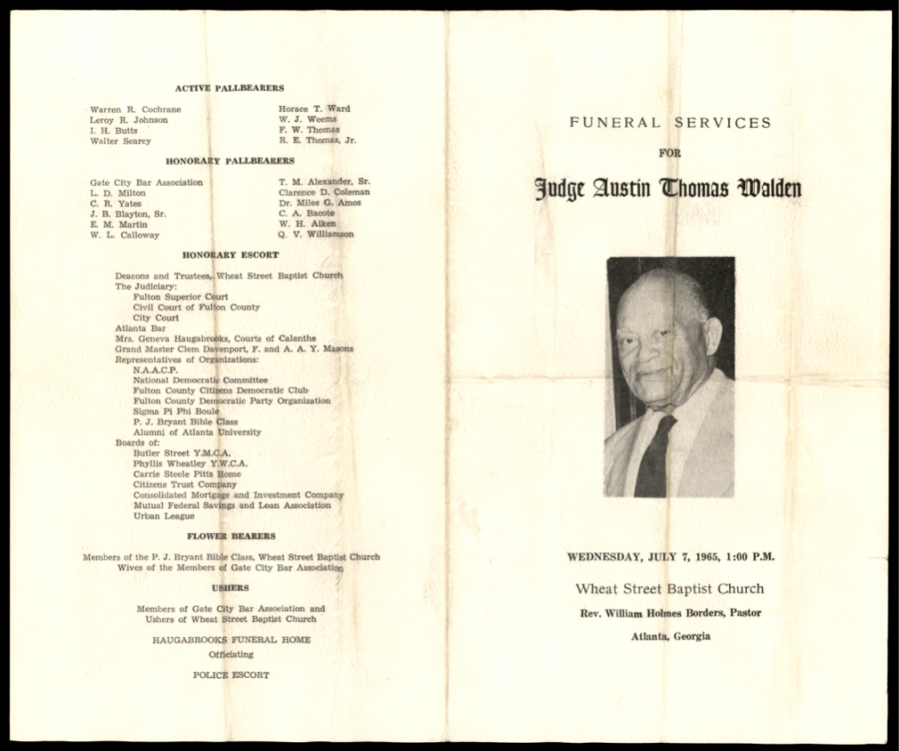

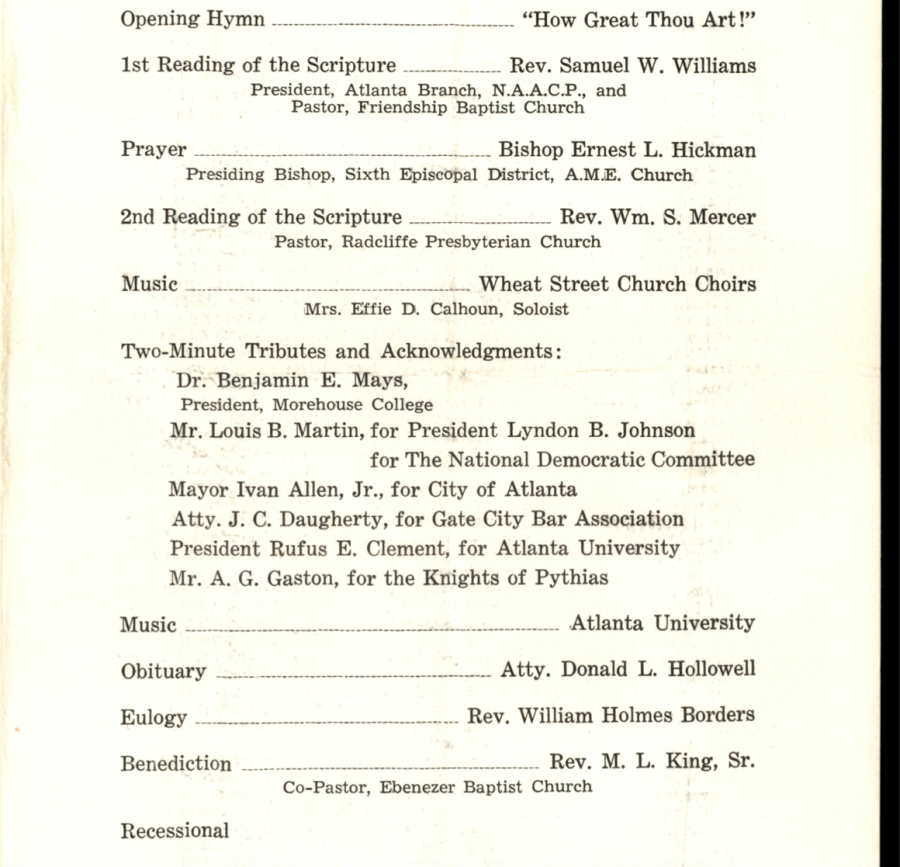

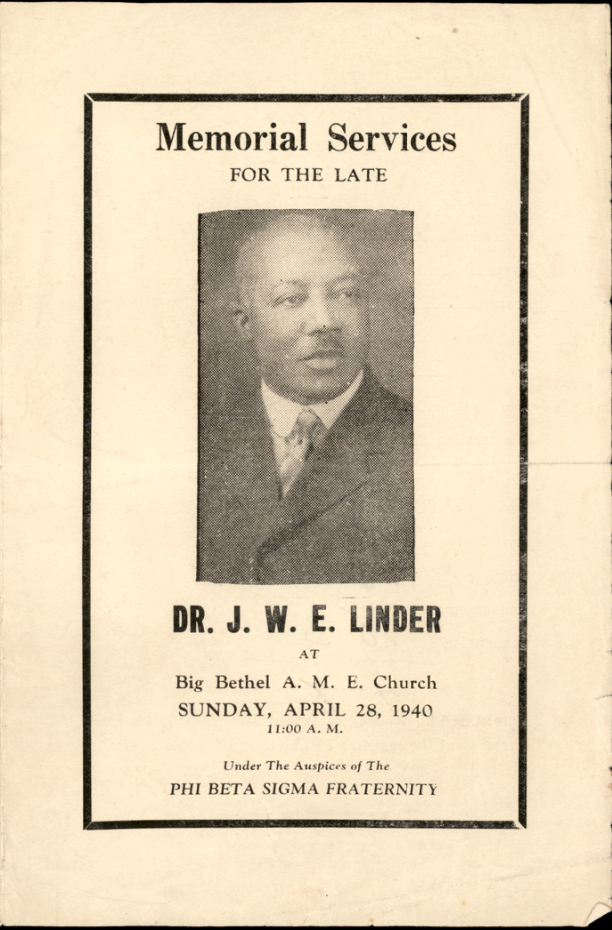

It is a way for local historians to recover important community figures. One program, for Dr. J.W.E. Linder, “who died in 1939,” Atlas Obscura’s Matthew Taub writes, “and whose memorial service was held in 1940” informs us that the deceased was the son of “Congressman George W. Linder, of the Georgia House of Representatives during the Reconstruction Period.” In the program for Judge Austin Thomas Walden, who died in 1965, we learn that he served as the first municipal judge in Georgia since Reconstruction. His benediction was delivered by the Reverend Martin Luther King Sr. and he received tributes from the Mayor of Atlanta, the President of Morehouse College, and the office of President Johnson.

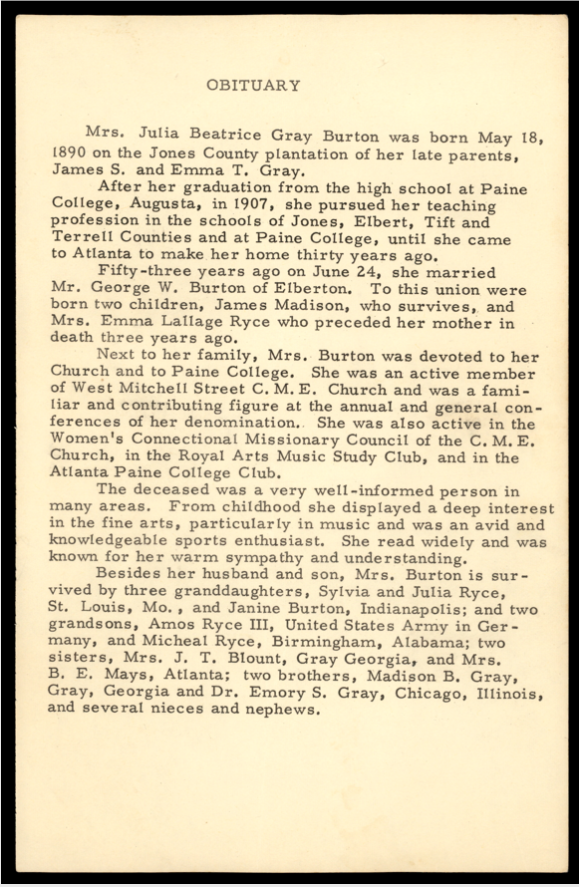

Such pillars of the community can be found among a host of programs memorializing ordinary, everyday people. The descriptions in the funeral literature open fascinating windows onto their lives and their extended family connections. Mrs. Julia Burton’s program from 1960, for example, tells us she was born on the plantation where her parents were likely enslaved. Her obituary not only describes her many clubs and her character as “a well-informed person in many areas,” but also lists the names of her husband and son, three granddaughters, two grandsons, two sisters, and two brothers—invaluable information for people searching for relatives.

“The challenge for African American genealogy and family research continues to be the lack of free access to historical information that can enable us to the tell the stories of those who have come before us,” remarks Tammy Ozier, president of the Atlanta Chapter of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society. “This monumental collection helps to close the gap.” As it grows, it will likely come to represent greater geographical areas around the country. For now, the roughly 3300 digitized funeral programs, some a single page, some elaborate, full-color productions, focus on an area to which thousands of families around the country can trace their lineage, and to which many may find their way back through public archives like this one.

via Atlas Obscura

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness