Statues of slaveholders and their defenders are falling all over the U.S., and a lot of people are distraught. What’s next? Mount Rushmore? Well… maybe no one’s likely to blow it up, but some honesty about the “extremely racist” history of Mount Rushmore might make one think twice about using it as a limit case.

On the other hand, a sandblasting of the enormous Klan monument in Stone Mountain, Georgia—created earlier by Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum—seems long overdue.

We are learning a lot about the history of these monuments and the people they represent, more than any of us Americans learned in our early education. But we still hear the usual defense that slaveholders were only men of their time—many were good, pious, and gentle and knew no better (or they agonized over the question but, you know, everyone was doing it….) People subjected to the violence and horror of slavery mostly tended to disagree.

Before the Haitian Revolution terrified the slaveholding South, many prominent slaveholders, Jefferson and Washington included, expressed intellectual and moral disgust with slavery. They could not consider abolition, however (though Washington freed his slaves in his will). There was too much profit in the enterprise. As Jefferson himself wrote, “It [would] never do to destroy the goose.”

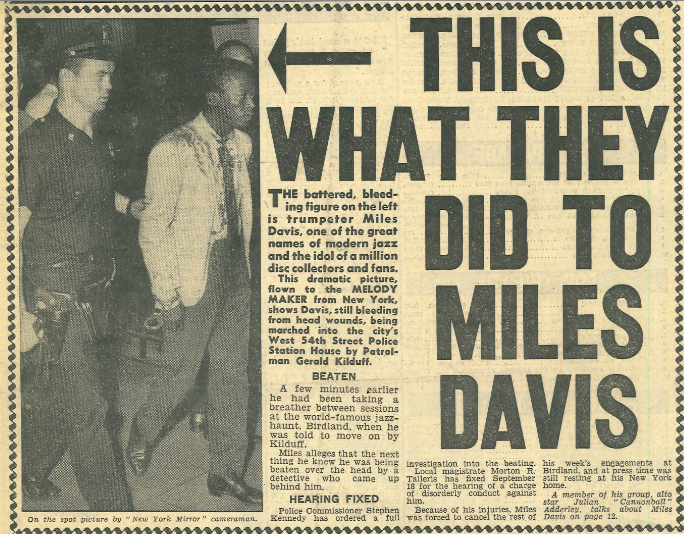

What we see when we look at the Revolutionary period is the fatal irony of a republic based on ideals of liberty, founded mostly by men who kept millions of people enslaved. The point is made vividly above in a virtual defacement of Declaration of Independence, John Trumbull’s famous 1818 painting which hangs in the U.S. Capitol rotunda. All of the founders’ faces blotted out by red dots were slaveowners. Only the few in yellow in the corresponding image freed the the people they enslaved.

These images were not made in this current summer of national uprisings but in August of 2019, “a bloody month that saw 53 people die in mass shootings in the US,” notes Hyperallergic. Their creator, Arlen Parsa sought to make a different point about the Second Amendment, but wrote forcefully about the founders’ enslaving of others. “There were no gentle slaveholders,” writes Parsa. “Countless children were born into slavery and died after a relatively short lifespan never knowing freedom for even a minute.” Many of those children were fathered by their owners.

Some founding fathers paid lip service to the idea of slavery as a blight because it was obvious that kidnapping and enslaving people contradicted democratic principles. Slavery happened to be the primary metaphor used by Enlightenment philosophers and their colonial readers to characterize the tyrannical monarchism they opposed. The philosopher John Locke wrote slavery into the constitution of the Carolina colony, and profited from it through owning stock in the Royal African Company. Yet by his later, hugely influential Two Treatises, he had come to see hereditary slavery as “so vile and miserable an estate of man… that ‘tis hardly to be conceived” that anyone could uphold it.

There were, of course, slaveholding founders who resisted such talk and felt no compunction about how they made their money. But lofty principles or no, the U.S. founders were often on the defensive against non-slaveholding colleagues, who scolded and attacked them, sometimes with frank references to the rapes of enslaved women and girls. These criticisms were so common that Thomas Paine could write the case for slavery had been “sufficiently disproved” when he published a 1775 tract denouncing it and calling for its immediate end:

The managers of [the slave trade] testify that many of these African nations inhabit fertile countries, are industrious farmers, enjoy plenty and lived quietly, averse to war, before the Europeans debauched them with liquors… By such wicked and inhuman ways, the English are said to enslave towards 100,000 yearly, of which 30,000 are supposed to die by barbarous treatment in the first year…

So monstrous is the making and keeping them slaves at all… and the many evils attending the practice, [such] as selling husbands away from wives, children from parents and from each other, in violation of sacred and natural ties; and opening the way for adulteries, incests and many shocking consequences, for all of which the guilty masters must answer to the final judge…

The chief design of this paper is not to disprove [slavery], which many have sufficiently done, but to entreat Americans to consider:

With that consistency… they complain so loudly of attempts to enslave them, while they hold so many hundred thousands in slavery and annually enslave many thousands more, without any pretence of authority or claim upon them.

Jefferson squared his theory of liberty with his practice of slavery by picking up the fad of scientific racism sweeping Europe at the time, in which philosophers who profited, or whose patrons and nations profited, from the slave trade began to coincidentally discover evidence that enslaving Africans was only natural. We should know by now what happens when racism guides science.…

Maybe turning those who willfully perpetuated the country’s most intractable, damning crime against humanity into civic saints no longer serves the U.S., if it ever did. Maybe elevating the founders to the status of religious figures has produced a widespread historical ignorance and a very specific kind of nationalism that are no longer tenable. Younger and future generations will settle these questions their own way, as they sort through the mess their elders have left them. As Locke also argued, in a paraphrase from American History professor Holly Brewer, “people do not have to obey a government that no longer protects them, and the consent of an ancestor does not bind the descendants: each generation must consent for itself.”

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness