Magician Andy Clockwise shows you how you can make “your very own Krispy Kreme face shield using just the lid from a 12 box of Krispy Kreme doughnuts, some sticky tape and a pair of scissors.”

If you need to improvise, you know what to do…

Magician Andy Clockwise shows you how you can make “your very own Krispy Kreme face shield using just the lid from a 12 box of Krispy Kreme doughnuts, some sticky tape and a pair of scissors.”

If you need to improvise, you know what to do…

Dolly Parton’s “Jolene” is an endlessly renewable resource of beautiful sadness, and many a modern-day bard has a “Jolene” in their quiver. The White Stripes turned it into garage rock, Olivia Newton John did it as disco, and Norah Jones as cabaret jazz. There is the obligatory house remix. Slow it down to 33rpm and Dolly’s gender begins to blur, while her voice loses none of its plaintive mystique. “Jolene” set a standard for melancholy few, if any, tunes can meet. So, you know, there’s a bardcore cover of “Jolene.”

Bardcore (also called “tavernwave”), has “taken over pop music,” kind of, as you might have learned from Ayun Halliday’s post on bardcore artist Hildegard von Blingin’ here a few weeks back. The short version—bardcore artists make covers of pop songs with medieval instrumentation and vocal stylings. Lyrics are rewritten with archaisms like “I want thine ugly, I want thy disease/Take aught from thee shall I if it can be free,” which are not lyrics to “Jolene,” let’s move on.

What does “Jolene” sound like as bardcore? In a word, spellbinding. And I don’t mean to be cheeky—this is enchanting, not least because, medievalized, the song sounds at times like it could be coming from a tortured nun on the edge of leaving the cloister in the dead of night to run off with a woman named Jolene, whose attributes she lovingly, poetically lays out.

Jolene, Jolene, Jolene, Jolene

I beg of thee, pray take not my lord

Jolene, Jolene, Jolene, Jolene

I fear, from thee, ‘twould take naught but a wordThy beauty is beyond compare

With flaming locks of auburn hair

With ivory skin and eyes of emerald green

Thy smile is like a breath of Spring

Thy voice is soft like Summer rain

And I cannot compete with thee

Jolene

An ode to jealousy hints at a potentially spicy tale of forbidden romance and broken vows, further tribute to Parton’s skill as a songwriter (and the sexual ambiguity inherent in the song). Hildegard von Blingin’ is not joking, novelty names aside. She has a lovely voice and has invested her medieval covers with high production values and period-correct illuminated music videos.

Everyone listens to house music in Hollywood sci-fi futures, but maybe it’s bardcore they’ll play on the interstellar cruise ships. “’Tis a veritable phenomenon on t’internet,” says bardcore creator Cornelius Link (which means it could go the way of vaporwave). For years, medieval memes have been hot online currency, for reasons we need not get too pop-sociological about. They’re fun and weird and alien and WTF and remind us that it could be worse, I guess. They appeal to Gen Z’s “existential humour.” They were Games of Thrones-y. They’re cooler than Harry Potter.

For most of medieval times, plague was on everyone’s mind. “The pandemic is thought to be significant,” says Link, “with a new Black Death hovering over us all.” But if we’re talking about “Jolene,” we’re talking about a song that “registers with the basest of bitterness we’ve all felt,” hither and thither, shut up in convents or locked down in our houses. Explore more not-“Jolene” bardcore jams here.

via Boing Boing

Related Content:

Dolly Parton’s “Jolene” Slowed Down to 33RPM Sounds Great and Takes on New, Unexpected Meanings

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The person who may or may not be Banksy is at it again, this time stenciling up a London Underground carriage with his familiar rat characters. Rats know a thing or two about spreading disease but this time they are here to insist that the public wear a mask. (Earlier in April they appeared in the artist’s own bathroom.)

As posted on Banksy’s social media feeds on Tuesday we can see the artist get kitted up like one of the Underground’s “deep cleaners”—-a protective face mask, goggles, blue gloves, white Tyvek bodysuit, and orange safety vest—and enter a carriage with an exterminator’s spray canister filled with light blue paint. He also has some of his stencils ready to go. “If you don’t mask, you don’t get” reads the video’s caption.

Currently all passengers must wear masks on the London Underground, and over the last month Transport for London has reported a 90% compliance rate (take note, America!). Workers have been sanitizing stations and trains more, and even installing UV light technology to battle the virus.

Banksy’s rats are shown using masks as parachutes, carrying bottles of hand sanitizer, and along one wall sneezing particles across the window, painted using the canister spray nozzle. Bansky tags the back wall with his name, urges a passenger to stay back while he works, and then gets off at a stop. He’s left one final message: “I get lockdown” (painted on a station wall) “but I get up again” (on the closing doors). The line is a nod to Chumbawumba’s inescapable 1997 anthem “Tubthumping.”

Banksy might be a rebellious street artist, but he’s not an idiot: wearing masks is imperative.

The artwork didn’t last long, as Transport of London has strict policies against graffiti. So few passengers even got to experience the art before it was scrubbed by workers, long before anybody would have identified it as a Banksy work.

“When we saw the video, we started to look into it and spoke to the cleaners,” a London Transport source told the New York Post. “It started to emerge that they had noticed some sort of ‘rat thing’ a few days ago and cleaned it off, as they should. It rather changes the aspect for anyone seeking to go down the route of accusing us of cultural vandalism.”

The Post even suggested that the carriage could have been removed and then sold as a complete art work in itself and raised money for charity. (They quote an art broker who values it at $7.5 million. But where would you hang it? In your private airplane hanger?)

Anyway, like a lot of Banksy work, it appeared, it was documented, and it was gone. Transport of London did mention that they were open to Banksy creating something else at a “suitable location,” but then again, that’s not how the artist rolls. Just keep your eyes open, folks, and look out for rats.

Related Content:

Behind the Banksy Stunt: An In-Depth Breakdown of the Artist’s Self-Shredding Painting

Banksy Strikes Again in Venice

Banksy Paints a Grim Holiday Mural: Season’s Greetings to All

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

As every grade schooler knows (and delights in working into conversation), cows have a tendency towards flatulence. At first this just deterred kids from going into animal husbandry, but now those kids have come to associate the phenomenon of farting livestock with a larger issue of interest to them: climate change. From cows’ rear ends comes methane, “one of the most harmful greenhouse gases and a major contributor to climate change,” as Adam Satariano puts it in a recent New York Times article on scientific research into the problem. “If they were a country, cows would rank as the world’s sixth-largest emitter, ahead of Brazil, Japan and Germany, according to data compiled by Rhodium Group, a research firm.”

For some, such bovine damage to the climate has provided a reason to stop eating beef. But that’s hardly the solution one wants to endorse if one runs a company like, say, Burger King. And so we have the Reduced Methane Emissions Beef Whopper, the product of a partnership “with top scientists to develop and test a new diet for cows, which according to initial study results, on average reduces up to 33% of cows’ daily methane emissions per day during the last 3 to 4 months of their lives.” The main effective ingredient is lemongrass, as anyone can find out by looking up the project’s formula online, where Burger King has made it public — or as the marketing campaign stresses, “open source.”

That campaign also has a music video, directed by no less an auteur of the form than Michel Gondry. In it the Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Be Kind Rewind filmmaker has eleven-year-old country musician Mason Ramsey and eight other Western-attired youngsters sing about the role of cow flatulence in climate change and Burger King’s role in addressing it. All of this presents a natural opportunity for Gondry to indulge his signature handmade aesthetic, at once clumsy and slick, childlike and refined. You may recognize Ramsey as the boy yodeling “Lovesick Blues” at Walmart in a video that, originally posted two years ago, has now racked up nearly 75 million views. Burger King surely hopes to capture some of that virality to promote its climate-mindedness — and, of course, to encourage viewers to have a Reduced Methane Emissions Beef Whopper “while supplies last.”

Related Content:

Michel Gondry’s Finest Music Videos for Björk, Radiohead & More: The Last of the Music Video Gods

Filmmaker Michel Gondry Presents an Animated Conversation with Noam Chomsky

The Coen Brothers Make a TV Commercial — Ridiculing “Clean Coal”

McDonald’s Opens a Tiny Restaurant — and It’s Only for Bees

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

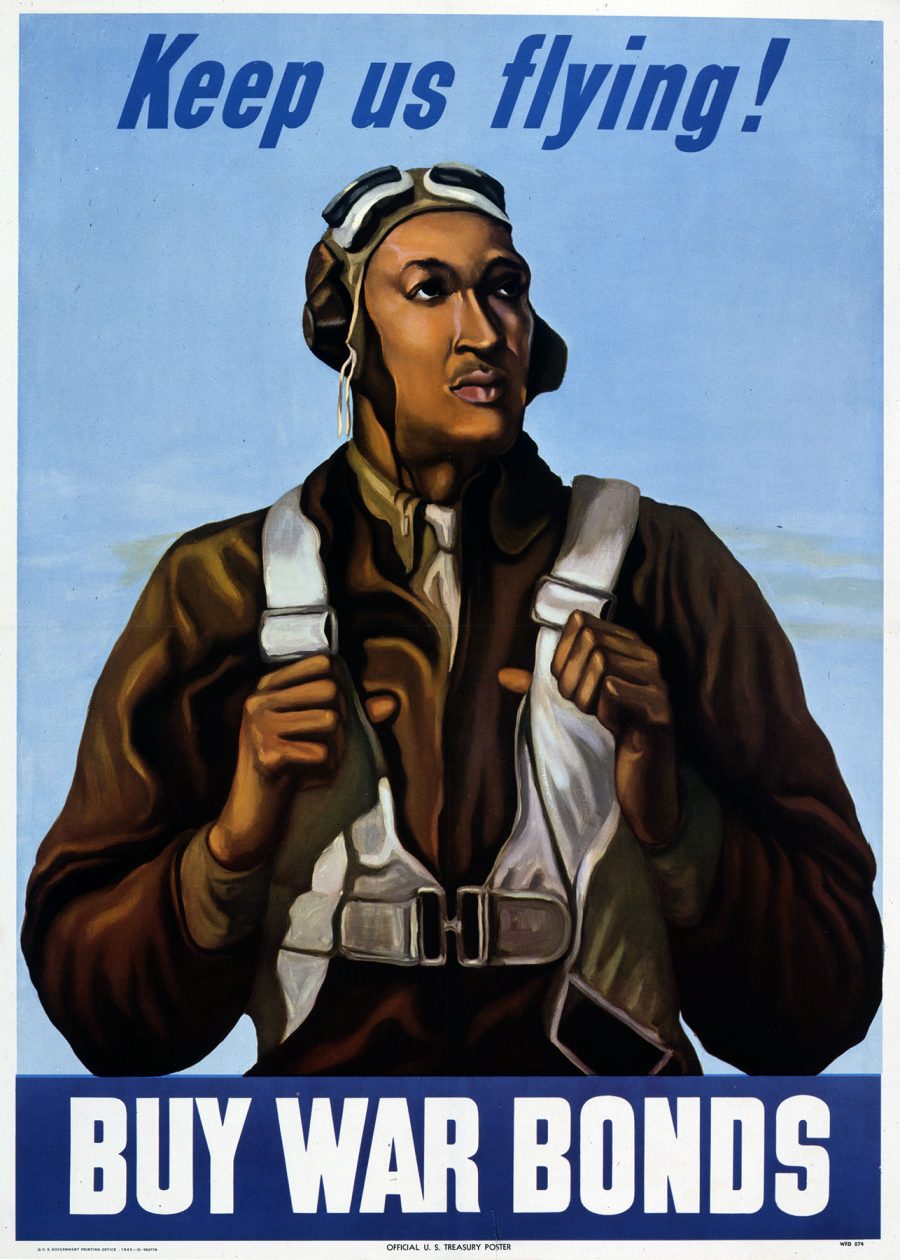

For decades, would-be black military pilots saw their possible future careers “canceled,” as they say, by racism in the segregated U.S. armed forces. Black servicemen “were denied military leadership roles and skilled training,” writes the official Tuskegee Airmen site, “because many believed they lacked qualifications for combat duty.” Aspiring airmen would finally, after campaigning since World War I, be given the chance to train and fly missions in the early forties, after “civil rights organizations and the black press exerted pressure that resulted in the formation of an all African-American pursuit squadron based in Tuskegee, Alabama.”

Actually trained on a dozen airfields around Tuskegee University, the airmen in the program “came away from those godforsaken Alabama fields with the unwavering belief that their newfound abilities might just help overcome prejudice, hearsay, and plain old dislike,” says Morgan Freeman in his voiceover narration for “Red Tails,” the short documentary above. The “Red Tails” or “Red Tail Angels,” as they were called after the distinctive color of their planes’ tails, roundly surpassed all expectations, becoming some of the most successful fighter pilots of the war.

“They would not be denied, despite the fact that they were unwelcome, unappreciated, and very much underestimated,” says Freeman. This is an understatement. The belief that African Americans lacked the capacity for complicated flight training was so prevalent that even the progressive Eleanor Roosevelt would give voice to it (in a demonstration to disprove it) when she visited the budding program in April 1941. “Can Negroes really fly airplanes?” she cheerfully asked the program’s head Charles “Chief” Anderson. He was obliged to give her a demonstration in his Piper J‑3 Cub, against the objections of her Secret Service detail.

Soon afterward, the first Negro Air Corps pilots began training, and the enlisted men chosen for the program became officers. Partly because of turnover among white senior officers in the program, who used it as a stepping stone to promotions and left after a few months, progress was slow. It wasn’t until September that Captain Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. was given the go-ahead for a solo flight, and not until April 1943 that the first squadron, the 99th, given combat clearance. Their story has passed into legend, from the claim that the Red Tails never lost a single bomber to the dramatic recreations of George Lucas’ Red Tails.

Later declassified documents appear to show that they had, in fact, lost bombers, like every other fighter group in the war. The fact hardly tarnishes the Tuskegee Airmen’s many medals or their prolifically attested skill and courage. It wouldn’t be until three years after the war ended that the military was finally desegregated, though the airmen themselves were lauded, promoted, and sought out by private industry when they returned to civilian life. Robert Friend, who died in 2019 at the age of 99, went on to serve in Korea and Vietnam, retired as a lieutenant colonel, worked on space launch vehicles, and formed his own aerospace company.

Charles McGee, who features in the short video documentary, just turned 100 this past February, and received a promotion to brigadier general. His reaction was ambivalent: “At first I would say ‘wow,’ but looking back, it would have been nice to have had that during active duty, but it didn’t happen that way. But still, the recognition of what was accomplished, certainly, I am pleased and proud to receive that recognition.”

Davis, the Tuskegee program’s first solo pilot and commander of the 99th Pursuit Squadron “was instrumental in drafting the Air Force plan to implement” desegregation in 1948, and he would become the Air Force’s first African American general. Davis’ father, it so happens, Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., had been the first black general in the U.S. Army. The Tuskegee Airmen were undoubtedly pioneers, but they were also part of a long tradition of black Americans who fought for the U.S. since its beginnings, “despite the fact,” as Freeman says, “that they were unwelcome, unappreciated, and very much underestimated.”

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Medical professionals have had a particularly difficult time getting people in the United States to act in unison for the public good during the pandemic. This has been the case with every step that experts urge to curb the spread of COVID-19, from closing schools, churches, and other meeting places, to enforcing social distancing and wearing masks over the nose and mouth in public spaces.

The resistance may seem symptomatic of the contemporary political climate, but there is ample precedent for it during the spread of so-called Spanish Flu, which took the lives of 675,000 Americans a little over a hundred years ago. Even when forced to wear masks by law or face jail time, many Americans absolutely refused to do so.

“In 1918,” writes E. Thomas Ewing at Health Affairs, “US public health authorities recommended masks for doctors, nurses, and anyone taking care of influenza patients.” The advisory “gradually and inconsistently” spread to the general public, in a different cultural climate, in some important respects, than our own, as University of Michigan medical historian J. Alexander Navarro explains.

Nationwide, posters presented mask-wearing as a civic duty – social responsibility had been embedded into the social fabric by a massive wartime federal propaganda campaign launched in early 1917 when the U.S. entered the Great War. San Francisco Mayor James Rolph announced that “conscience, patriotism and self-protection demand immediate and rigid compliance” with mask wearing. In nearby Oakland, Mayor John Davie stated that “it is sensible and patriotic, no matter what our personal beliefs may be, to safeguard our fellow citizens by joining in this practice” of wearing a mask.

Despite the civic spirit and generalized public support for mask wearing, passing local mask ordinances was “frequently a contentious affair.” Debates that sound familiar raged in city councils in Los Angeles and Portland, both of which rejected mask orders. (One official declaring them “autocratic and unconstitutional.”) San Francisco, on the other hand, brought the police down on anyone who refused to wear a mask, imposing fines and jail time.

These measures were adopted by other cities, as well as abroad in Paris and Manchester. “Fines ranged,” Navarro writes, “from US$5 to $200,” a huge amount of money in 1918, and a good amount for many people out of work today. Even in cities that did not impose harsh penalties, “noncompliance and outright defiance quickly became a problem.” Much of the resistance to wearing masks, however, came later, after a first wave of flu infections subsided. When precautions were relaxed, cases rose once again, and new mask mandates went into effect in 1919.

San Francisco’s Anti-Mask League formed in protest, attracting somewhere between 4,000 and 5,000 unmasked attendees to a January meeting. Some of their objections rested on an early study that found scant evidence for the efficacy of compulsory mask-wearing. However, a later comprehensive 1921 study by Warren T. Vaughn, notes Ewing, found that the data was too sketchy to draw conclusions: “The problem was human behavior: Masks were used until they were filthy, worn in ways that offered little or no protection, and compulsory laws did not overcome the ‘failure of cooperation on the part of the public.’”

Vaughn concluded, “It is safe to say that the face mask as used was a failure.” Many behaviors contributed to this outcome. As we see in the photograph at the top of anonymous Californians wearing masks and holding a sign that reads, “Wear a mask or go to jail,” many did not wear masks properly, leaving their nose exposed, for example, like the woman in the center of the group. Notably, instead of social distancing, the group stands shoulder to shoulder, rendering their masks mostly ineffective.

The kind of masks most people wore were made of thin gauze. (“Obey the laws and wear the gauze. Protect your jaws from septic paws,” went a jingle at the time.) The material wasn’t at all effective at closer distances, where today’s quilted cotton masks, on the other hand, have been shown to stop the virus a few inches from the wearer’s face. Still, masks, when combined with other measures, were shown to be effective when compliance was high, though much of the evidence is anecdotal.

What can we learn from this history? Does it undermine the case for masks today? “We need to learn the right lessons from the failure of flu masks in 1918,” Ewing argues. The overwhelming scientific consensus is that masks are some of the most effective tools for slowing the spread of the coronavirus, and that, unlike in 1918, “Masks can work if we wear them correctly, modify behavior appropriately, and apply all available tools to control the spread of infectious disease.”

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Jazz has always had big personalities. In the mid-20th century, an explosion of major players became as well known for their personal quirks as for their revolutionary techniques and compositions. Monk’s endearing oddness, Miles Davis’ brooding bad temper, Charles Mingus’ exuberant shouts and rages, Ornette Coleman’s cryptic philosophizing, Coltrane’s gentle mysticism…. These were not only the jazz world’s greatest players; they were also some of the century’s most interesting people.

The same can be said for Julian Edwin “Cannonball” Adderley, saxophonist and bandleader who was heralded as a new Charlie Parker on arrival in the New York scene from Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, where he had worked as a popular high school band director and local musician before deciding to pursue graduate studies. Music had other plans for him. Instead of going back to school when he arrived in Manhattan in 1955, he fell in with the right crowd and became an instant critical sensation.

Adderley ended up playing onstage and recording with greats like Davis, Coltrane, Art Blakey, Bill Evans, and his brother, Nat Adderley, who joined him to play in his Quintet, completed the Cannonball Adderley Sextet in the sixties with Yusef Lateef, and helped him make some of the best music of his career. Adderley joined Miles Davis’s band when Coltrane left and played on Kind of Blue and Milestones, leaving “a deep impression on Davis and his sextet,” notes one biography.

Unlike some of his famous peers, Adderley had none of the traits of the difficult or enigmatic artiste. Where most jazz musicians remained silent and mysterious onstage, Adderley engaged boisterously with his audience, in monologues one can imagine him shouting gregariously over a band room full of students warming up. With his irrepressible charm, he established an “amusing and educational rapport with his audience, often-times explaining what he and his musicians were about to play” (hear him do so before launching into his popular 1966 soul jazz single “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” below.)

Adderley’s personality helped put jazz newcomers at ease, but he didn’t teach from the textbook, experimenting broadly with several genres and incorporating electronic elements and African polyrhythms in the 60s and 70s, when he also became “a jazz spokesman. Whether it was television, residencies at several colleges, or film appearances.” Adderley helped pioneer soul jazz, post-bop, and other experimental subgenres, many of which crossed over into the pop charts. “Two words best encapsulate the music of alto saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderley,” writes Nick Morrison at NPR: “’joy’ and ‘soul.’”

The Polyphonic video at the top focuses on the role of joy in Adderley’s music, making the case that he “exemplifies joy more than anyone else in jazz.” His voracious appetite for life—reflected in his high school nickname “Cannibal,” which morphed into “Cannonball”—propelled him into the “center of the jazz universe.” It also led him to devour influences other jazz musicians avoided. He had no pretensions to jazz as high art, though he was himself a high artist, and he joyfully embraced pop music at a time when it was scorned by the jazz elite.

“Adderley’s great ambition was to share the joy of jazz with the world, and he knew that no matter how technically impressive a piece of music was, people wouldn’t listen to it if it wasn’t fun, so Cannonball made his music fun and accessible.” Records like The Cannonball Adderley Sextet in New York sound like “a party,” writes CJ Hurtt at Vinyl Me, Please: “a party with some far-out nearly free jazz post-bop elements to it” but no shortage of straight-ahead grooves. The album kicks off with Cannonball “telling the audience that they are actually hip and not merely pretending to be.” It’s tongue-in-cheek, of course; Adderley never pretended to be anyone but his own outgoing self. But his unrelenting cheerfulness, even when he played the blues, also made him one of the hippest cats around.

Related Content:

How Jazz Helped Fuel the 1960s Civil Rights Movement

Herbie Hancock’s Joyous Soundtrack for the Original Fat Albert TV Special (1969)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness

In recent years, viewers the world over have been binge-watching a Japanese reality show called Terrace House. The New Yorker’s Troy Patterson describes its format thus: “Three men and three women move into an elegant pad for a spell, while otherwise conducting their lives as usual. The members of the cast are above average in their camera-readiness and their civility, and in no other discernible way.” Fueled not by the self-promotional showboating and ginned-up resentment that have become conventions of Terrace House’s Western predecessors, “the show’s slow-burning action is sparked by the honest friction of minor personality flaws and conflicting personal needs,” making it “closer to a nature documentary than to the exploitation films that one has come to expect from reality television.”

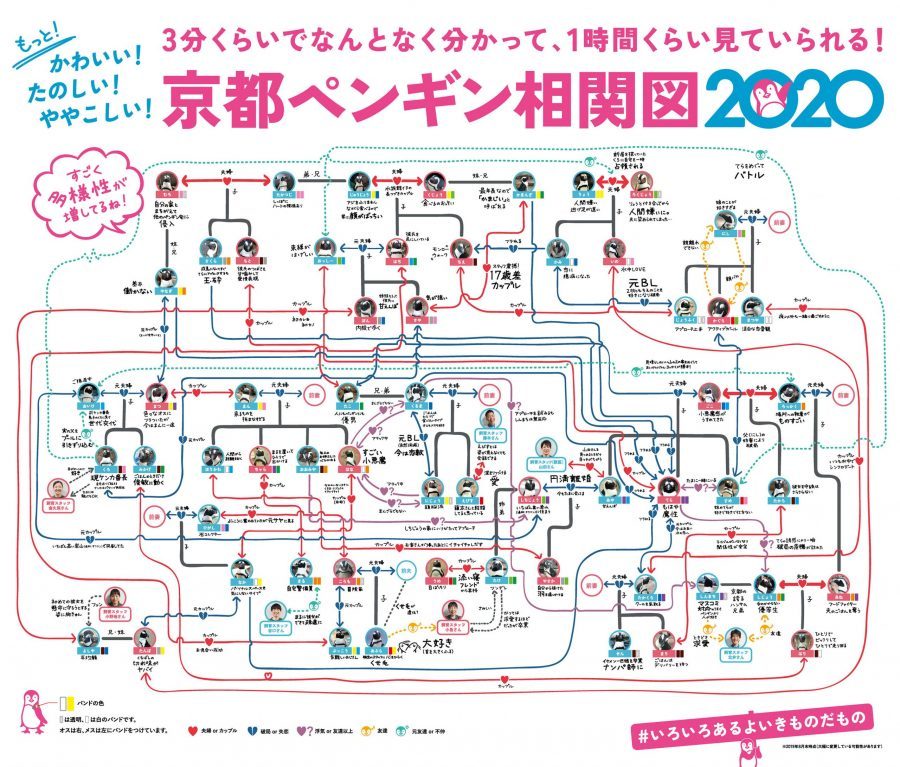

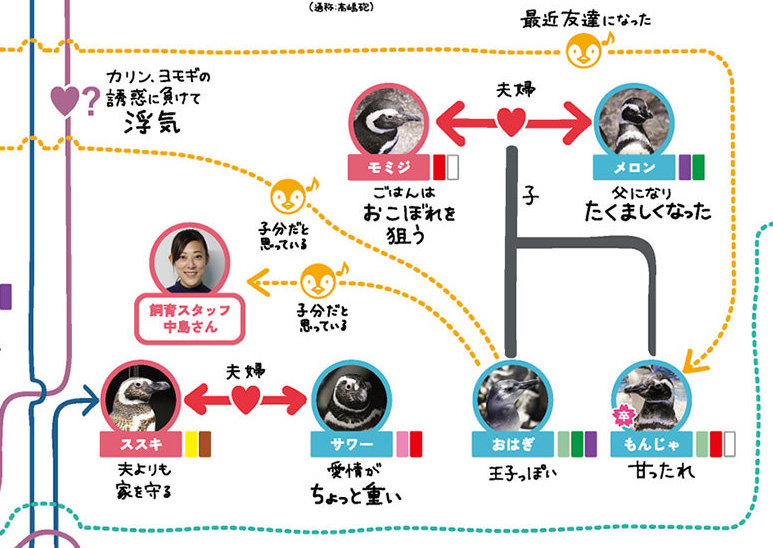

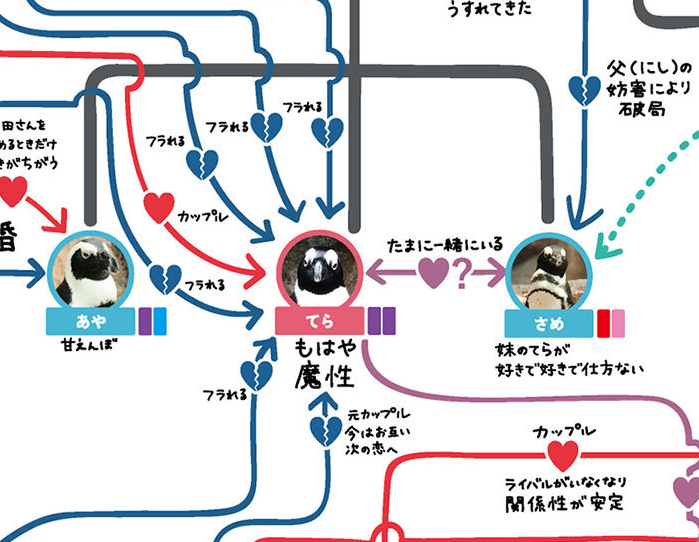

If viewing human beings the way we’re used to viewing nature can give us such satisfaction, how about viewing nature the way we’re used to viewing human beings? Japan, as Johnny Waldman reports at Spoon and Tamago, has led the way in both reversals: “Two aquariums in Japan, Kyoto Aquarium and Sumida Aquarium, keep obsessive tabs on their penguins and maintain an updated flowchart that visualizes all their penguin drama.”

Waldman quotes Japan-based researcher Oliver Jia as tweeting the fact that “Penguin drama actually isn’t totally unexpected. They’re known to be vicious animals who cheat on their partners and steal other’s children. So basically, your average day in Los Angeles” — the cradle, one might add, of the reality-TV industry.

Though the lives of penguins may, in the eyes of the aquarium-visiting layman, appear to consist entirely of swimming, eating fish, and standing around, the animals’ “romantic escapades are fairly easy to observe,” at least according to Waldman’s translation of the penguin caretakers at the Sumida Aquarium. “Wing-flapping is a sign of affection and couples can be seen grooming each other. Penguins who are getting over a break-up will often refuse to eat.” This is the kind of observational data that inform the intensively detailed (and cuteness-optimized) penguin-relationship diagrams seen here, high-resolution versions of which you can download from the Kyoto Aquarium and Sumida Aquarium’s web sites. Now that Terrace House has come to an end, perhaps the time has come on Japanese reality television for a bit of non-human drama.

Related Content:

Act of Love: A Strange, Wonderful Visual Dictionary of Animal Courtship

See Penguins Wearing Tiny “Penguin Books” Sweaters, Knitted by the Oldest Man in Australia

Japanese Designer Creates Incredibly Detailed & Realistic Maps of a City That Doesn’t Exist

The First Museum Dedicated to Japanese Folklore Monsters Is Now Open

Discover the Japanese Museum Dedicated to Collecting Rocks That Look Like Human Faces

Meet Congo the Chimp, London’s Sensational 1950s Abstract Painter

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Something’s strange… Is it a dream? If it’s a morality tale with a twist ending, you’re probably in the Twilight Zone. Your hosts Brian Hirt, Erica Spyres, and Mark Linsenmayer, plus guest Ken Gerber (Brian’s brother) are in it this week, discussing the thrice revived TV series. Does the 1959–1963 show hold up? What makes for a good TZ episode, and does Jordan Peele’s latest iteration capture the spirit? We talk about episodes new and old, the 1983 film, plus comparisons to Black Mirror and David Lynch.

The classic episodes we focus most on (and might spoil, so you should go watch them) are It’s a Good Life, Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up?, What You Need, The Howling Man, Perchance to Dream, and Nick of Time. The others Ken recommended for us are The Obsolete Man and The Masks. Mark complains about Walking Distance.

In the new series, season 1, we do spoil Blurry Man and praise (but don’t spoil) Replay. We don’t spoil season two at all, but recommend Try, Try and Meet in the Middle and pan Ovation and 8.

Some articles we looked at include:

A good video on the background of the show is “American Masters Rod Serling: Submitted for your Approval,” and you can find detailed discussions of many episodes on The Twilight Zone Podcast. Ken recommends The Twilight Zone Companion. Oh, and Chris Hardwick really likes TZ.

If you enjoyed this episodes, you might like our previous discussion with Ken on time travel.

Learn more at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes bonus discussion that you can only hear by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This week, we continue for more than half an hour, further discussing the Twilight Zone with Ken, which includes a look at the 1985–1989 series.

This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts.

You’re held captive in an enclosed space, only able faintly to perceive the outside world. Or you’re kept outside, unable to cross the threshold of a space you feel a desperate need to enter. If both of these scenarios sound like dreams, they must do so because they tap into the anxieties and suspicions in the depths of our shared subconscious. As such, they’ve also proven reliable material for storytellers since at least the fourth century B.C., when Plato came up with his allegory of the cave. You know that story nearly as surely as you know the ancient Greek philosopher’s name: a group of human beings live, and have always lived, deep in a cave. Chained up to face a wall, they have only ever seen the images of shadow puppets thrown by firelight onto the wall before them.

To these isolated beings, “the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images.” So Orson Welles tells it in this 1973 short film by animator Dick Oden. In his timelessly resonant voice that complements the production’s hauntingly retro aesthetic, Wells then speaks of what would happen if a cave-dweller were to be unshackled.

“He would be much too dazzled to see distinctly those things whose shadows he had seen before,” but as he approaches reality, “he has a clearer vision.” Still, “will he not be perplexed? Will he not think that the shadows which he formerly saw are truer than the objects which are now shown to him?” And if brought out of the cave to experience reality in full, would he not pity his old cavemates? “Would he not say, with Homer, better to be the poor servant of a poor master and to endure anything rather than think as they do and live after their manner?”

Plato’s cave wasn’t the first parable of the human condition Welles narrated. Just over a decade earlier, he engaged pinscreen animator Alexandre Alexeieff (he of Night on Bald Mountain and and “The Nose,” previously featured here on Open Culture) to illustrate his reading of Franz Kafka’s story “Before the Law.” The law, in Kafka’s telling, is a building, and before that building stands a guard. “A man comes from the country, begging admittance to the law,” says Welles. “But the guard cannot admit him. May he hope to enter at a later time? That is possible, said the guard.” Yet somehow that time never comes, and he spends the rest of his life awaiting admission to the law. “Nobody else but you could ever have obtained admittance,” the guard admits to the man, not long before the man expires of old age. “This door was intended only for you! And now, I’m going to close it.”

“Before the Law” describes a grimly absurd situation, as does Welles’ The Trial, the film to which it serves as an introduction. Adapted from another work of Kafka’s, specifically his best-known novel, it also concerns itself with the legal side of human affairs, at least on the surface. But when it becomes clear that the crime with which its bureaucrat protagonist Josef K. has been charged will never be specified, the story plunges into an altogether more troubling realm. We’ve all, at one time or another, felt to some degree like Joseph K., persecuted by an ultimately incomprehensible system, legal, social, or otherwise. And can we help but feel, especially in our highly mediated 21st century, like Plato’s immobilized human, raised in darkness and made to build a worldview on illusions? As for how to escape the cave — or indeed to enter the law — it falls to each of us individually to figure out.

Related Content:

Plato’s Cave Allegory Animated Monty Python-Style

Plato’s Cave Allegory Brought to Life with Claymation

The Philosophy of The Matrix: From Plato and Descartes, to Eastern Philosophy

Kafka’s Nightmare Tale, “A Country Doctor,” Told in Award-Winning Japanese Animation

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

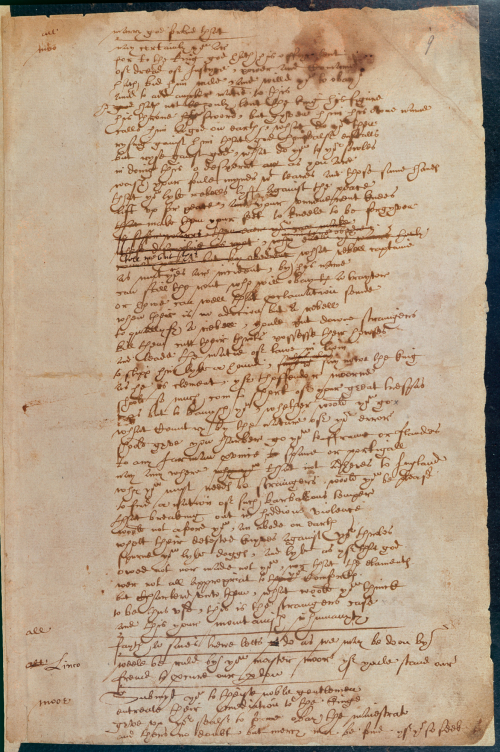

Four years ago, when the world commemorated the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death, some marked the event with reference to a dramatic work hardly anyone’s ever read, and fewer have ever seen performed. Called The Booke of Sir Thomas More, “this late 16th or early 17th-century play,” the British Library notes, “is not always included among the Shakespearean canon, and it was not until the 1800s that it was even associated with the Bard of Avon.”

Since then, Sir Thomas More has become famous, at least among literary scholars, as the only surviving example of Shakespeare’s handwriting next to his will. It also became briefly internet famous in 2016 when Sir Ian McKellen reprised the title role he first played in 1964 for a dramatic reading in London that spoke eloquently, centuries later, to the moment. The play itself is the work of several dramatists, and the original text, from sometime between 1590 and 1605, is a patchwork of pages of insertions and six different scribal hands, Shakespeare’s very likely among them.

That same year, the British Library put a scan of the Shakespeare-penned pages of the play online and put the physical manuscript on display in an exhibit called Shakespeare in Ten Acts. Now, they have uploaded the full, scanned manuscript to their Digitized Manuscripts page and you can view it here. “In these pages we can perhaps see the master playwright at work, musing, composing and correcting his text: a window into Shakespeare’s dramatic art, as it were.” We can hear what McKellen calls the “human empathy” in a speech “symbolic and wonderful… so much at the heart of Shakespeare’s humanity.”

The speech, which McKellen discusses above, has the humanist More passionately addressing a mob who are attempting to violently deport French protestant refugees. More did indeed address a rioting mob on May 1, 1517, what came to be known as “Evil May Day” (he was later executed in 1535 for treason when he refused to back Henry VIII against the Catholic Church). The play, which shows his actions as especially heroic, was censored by Edwin Tilney, Master of the Revels, and never performed until McKellen took the role. (He has joked that he may be “the last actor who can say ‘I created a part written by William Shakespeare.’”)

Read a transcription of the full, 147-line More speech thought to be by Shakespeare, and written in his own hand, at Quartz. “Proving that More’s words were indeed written by Shakespeare is not straightforward,” the British Library notes, though scholars have generally agreed on the authorship since the late 19th century, based on evidence you can read about here. But “in their keen sympathy for the plight of the alienated and dispossessed,” these lines “seem to prefigure the insights of great dramas of race such as The Merchant of Venice and Othello.”

One can see, given Shakespeare’s sympathy for social outsiders, why he would be drawn to More’s speech, or why he might have been handpicked among other dramatists at the time to write the philosopher’s broad-minded plea for tolerance. See the full manuscript of The Booke of Sir Thomas More here at the British Library’s Digitized Manuscripts.

Related Content:

What Shakespeare’s Handwriting Looked Like

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness