Fred Van Lente has written for more than 15 years for his own Evil Twin Comics, Marvel and other outlets. In this episode of Pretty Much Pop, he joins your hosts Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt to discuss comics as an idiosyncratic form of literature.

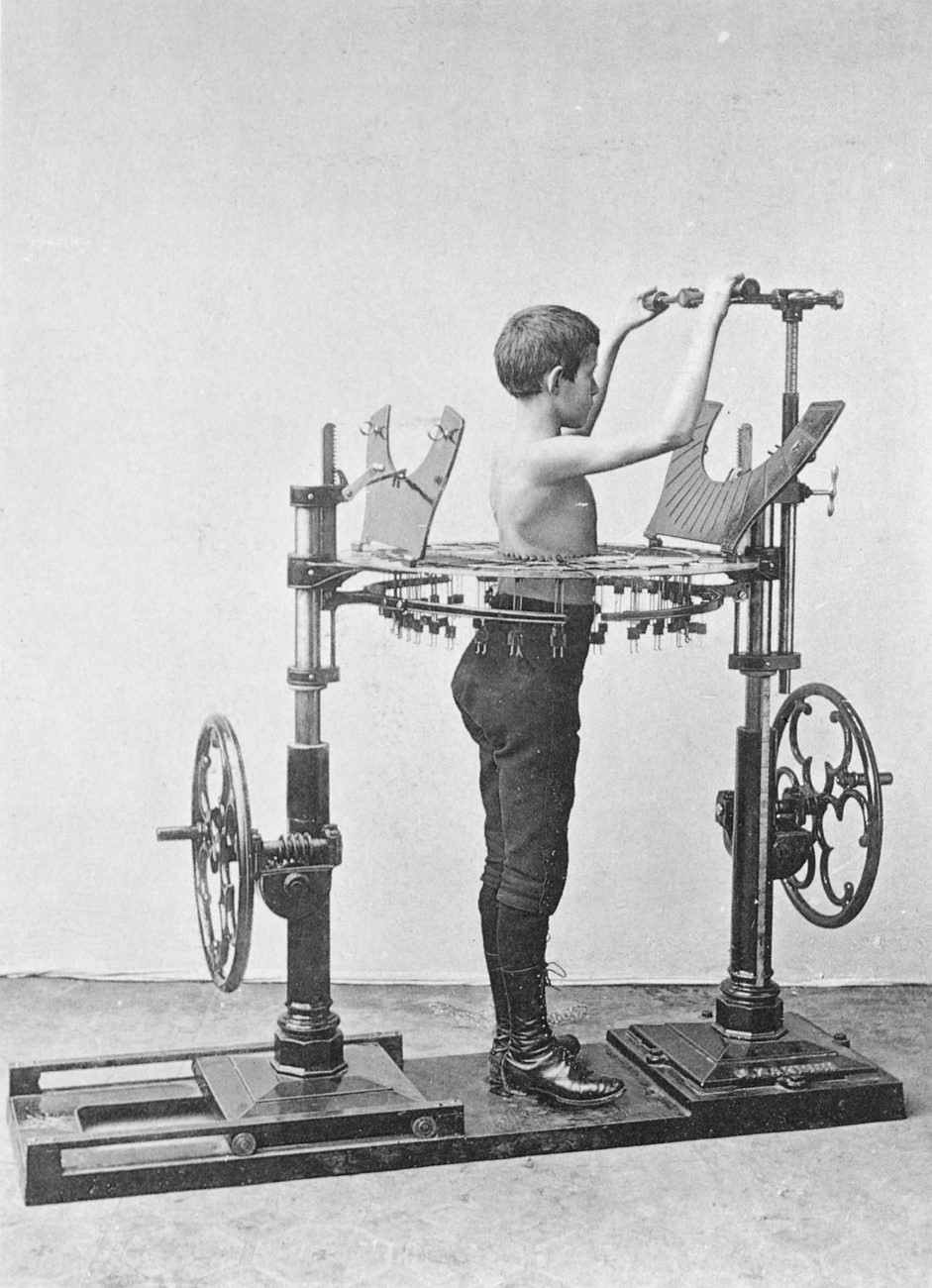

In the realm of non-fiction, Ryan started with the beloved Action Philosophers! series in 2004 with illustrator Ryan Dunlavey, and this team has gone on to create the very successful Comic Book History of Comics, plus more recently Action Presidents, Action Activists (available free in association with the NYC Department of Education’s Civics for All program), and have just begun releasing The Comic Book History of Animation. While the non-fiction comics format is common in places like Japan, and has a storied history in America, having been used to train soldiers in World War II, this is still something of a novelty in America as comics still struggle to overcome their reputation in (as Ryan puts it) “trash for morons.” Given that visual content is well known to help people learn as compared to text alone, the use of tools like Action Presidents in classrooms shouldn’t be surprising.

The interview also gets into Ryan’s fiction work, from Cowboys & Aliens, which was turned into a 2011 Jon Favreau/Steven Spielberg film entirely without Ryan’s involvement, to titles like Marvel Zombies and X‑Men Noir which use alternate dimension versions of popular characters to tell stories too dark and/or whimsical to have much possibility of ever being transferred to the screen. Despite comics’ reputation as being basically like elaborate film story-boards, their low overhead is exactly what distinguishes them so strongly from film: Their creativity is unlimited by budget, and creators can take tremendous risks. Whatever the mainstream palatability of (alternate dimension) Peter Parker eating Aunt May’s brain, this has been one of the most popular things that Ryan’s been involved with among comic book readers.

Learn more about Fred’s work at fredvanlente.com. You can read there about how Fred constructs scripts; the one Mark refers to with the mysteriously changed coat is right there highlighted at the top of this page, and there are also several sample scripts including the one for Action Philosophers: Immanuel Kant that demonstrates Fred’s methods for vividly explaining a complex idea.

Hear more of this podcast at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes bonus discussion you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts.