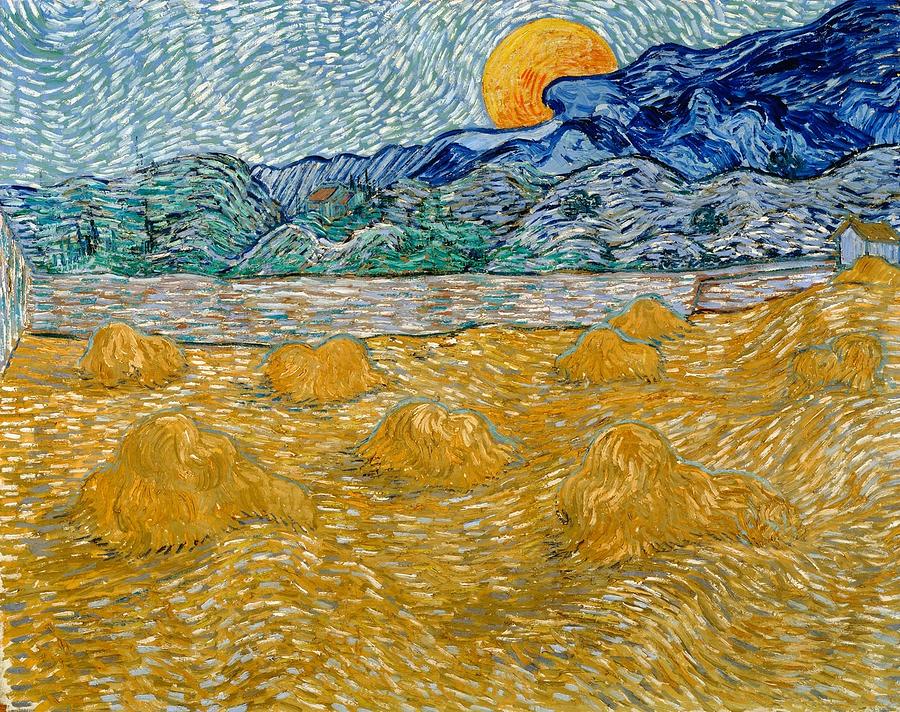

It gets dark before dinner now in my part of the world, a recipe for seasonal depression. Vincent van Gogh wrote about such low feelings with deep insight. “One feels as if one were lying bound hand and foot at the bottom of a deep dark well, utterly helpless.” Yet, when he looked up at the night sky he saw not darkness but blazing light: a full moon shines yellow from White House at Night like the sun, and peeks like a gold coin from behind blue mountains in Landscape with Wheat Sheaves and Rising Moon. The stars in Starry Night Over the Rhône appear like fireworks. We are all familiar with the blazing night sky of its sequel, The Starry Night.

It’s been suggested that Van Gogh saw halos of light because of lead poisoning from his paint, and that the Digitalis Dr. Gachet prescribed for his temporal lobe epilepsy caused him to “see in yellow,” the Van Gogh Gallery Blog writes, “or see yellow spots which could explain van Gogh’s consistent use of the color yellow in his later works.”

His most brilliant works date from this later period, during his time at the hospital at Arles, where he painted his famous bedroom. All of these paintings, and hundreds more, can be found in high-resolution scans at the new van Gogh resource, Van Gogh Worldwide, “a consortium of museums,” notes Madeleine Muzdakis at My Modern Met, “doing their part to bring the work of one of the world’s most famous artists to the global masses.”

The museums represented here are all in the Netherlands and include the Van Gogh Museum, Kröller-Müller Museum, the Rijksmuseum, the Netherlands Institute for Art History, and the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. Van Gogh was not only a prolific painter, of shining night scenes and otherwise, but he was “also a prolific sketch artist. His pencil and paper drawings are worth exploration; they depict landscapes as well as emotive figures from Van Gogh’s everyday life. Van Gogh Worldwide provides insight into these works of art and the artist behind them. One can also find behind-the-scenes museum information, such as details of restorations, verso (back) images, and other curatorial notes.”

Van Gogh Worldwide expands other digital collections like the Van Gogh Museum’s almost 1,000 online works. Where that resource includes short informational articles and links to literature about the artworks, Van Gogh Worldwide does not, as yet, feature such additional materials, but it does include links to Van Gogh’s letters. In one of them, he writes to his brother, Theo, about their parents: “They’ll find it difficult to understand my state of mind, and not know what drives me when they see me do things that seem strange and peculiar to them—will blame them on dissatisfaction, indifference or nonchalance, while the cause lies elsewhere, namely the desire, at all costs, to pursue what I must have for my work.”

Related Content:

Take a Journey Inside Vincent Van Gogh’s Paintings with a New Digital Exhibition

In a Brilliant Light: Van Gogh in Arles–A Free Documentary

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness