Brian Eno may not have invented ambient music, but he did give it a name. What better to call an album like his 1978 Music for Airports, whose slowly shifting pieces forego not just melody but all then-accepted methods of composition and performance? The result, as its title suggests, is meant not to occupy the intention of the listener but to color the atmosphere of a space. This marked one evolutionary step for an idea Eno first essayed in 1975’s Discreet Music, issued on his own label Obscure Records in an era when much of the music people listened to was anything but discreet. Recording technology first made ambient music possible; by the mid-1980s, video technology had developed to the point that it could possess a visual dimension as well.

Just as Eno’s ambient music wasn’t made for listening, Eno’s “video paintings,” as he called them, weren’t made for viewing. 1981’s Mistaken Memories of Medieval Manhattan, previously featured here on Open Culture, captures the urban landscape outside from Eno’s New York window — ironically, with a portrait orientation, so that any TV displaying it had to be turned on its side.

Thursday Afternoon, the next in the series, looks not to the built environment but that other traditional subject of painting, the female form: specifically that of Eno’s friend, photographer Christine Alicino. Here video making possible something truly new, with no artistic connection to, as Eno put it, “Sting’s new rock video” or “boring, grimy ‘Video Art.’ ”

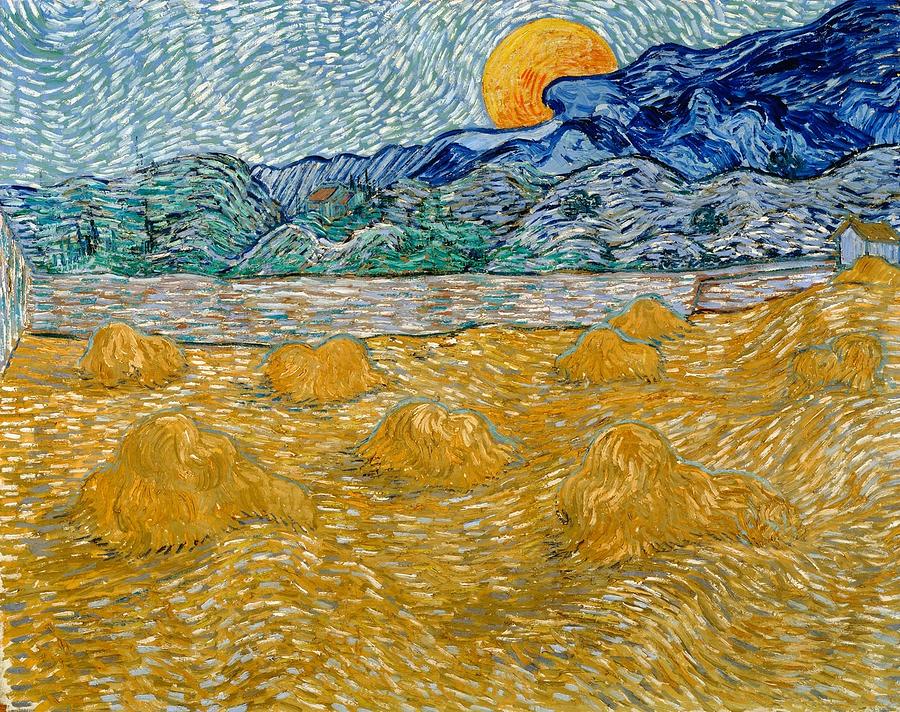

But just like a Hollywood movie, Thursday Afternoon had an eponymous soundtrack album. Released in 1985, it cut the 80-minute video painting’s ambient score down to an unbroken track of nearly 61 minutes, a length made possible by the recently introduced Compact Disc. “Played” on an acoustic piano and synthesizers, the music shifts subtly in texture throughout the hour, creating a sonic environment that many have found highly congenial for working, thinking, and relaxing. I myself have listened to it hundreds of times over the past twenty years, and in the form of a Youtube video painting made by fan Jonathan Jolly, it’s racked up more than four million views. The color-treated time-lapse footage of passing clouds fits right in with the spirit of the music, and it certainly seems to do the trick for the video’s commenters, grateful as they are for reduced anxieties, recovered memories, increased focus, and even altered consciousness.

Related Content:

A Six-Hour Time-Stretched Version of Brian Eno’s Music For Airports: Meditate, Relax, Study

Watch Brian Eno’s “Video Paintings,” Where 1980s TV Technology Meets Visual Art

Brian Eno Explains the Loss of Humanity in Modern Music

Brian Eno on Creating Music and Art As Imaginary Landscapes (1989)

The “True” Story Of How Brian Eno Invented Ambient Music

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.