Photo by Guilhem Vellut

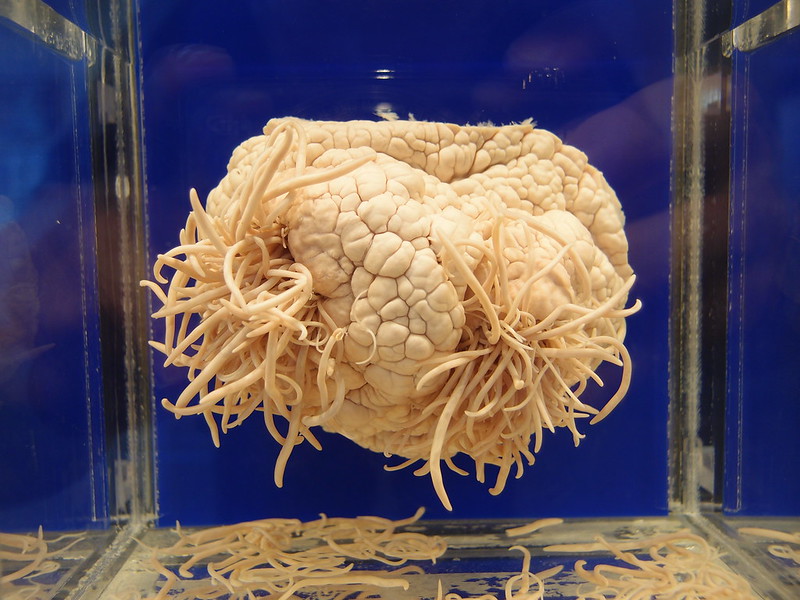

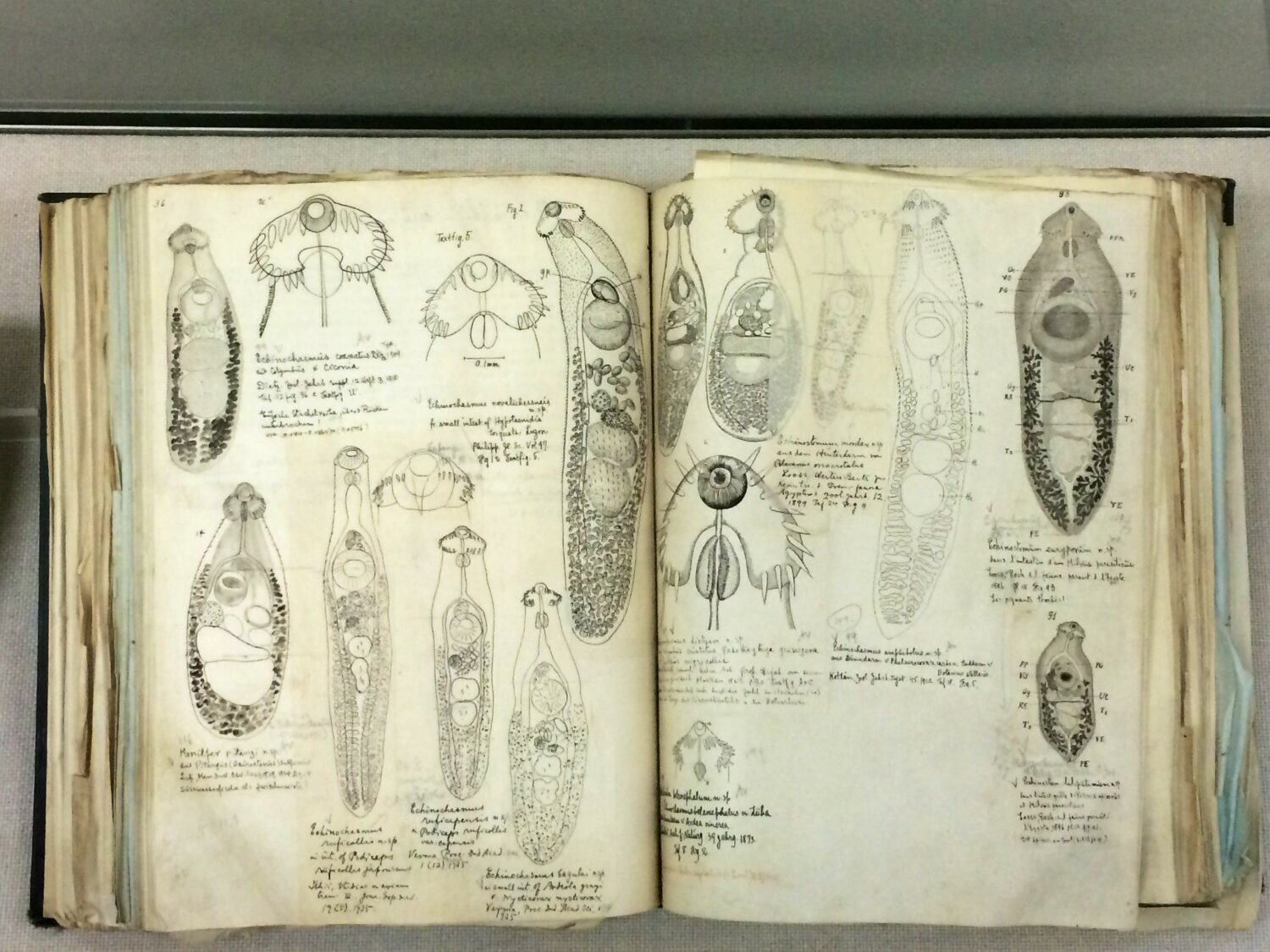

Weary as we are of hearing about not just the coronavirus but viruses in general, shall we we turn our attention to parasites instead? The Meguro Parasitological Museum has been concentrating its intellectual and educational energies in that direction since 1953. Located in the eponymous neighborhood of Tokyo, it houses more than 60,000 species of parasite, with more than 300 on display at any given time. “On the first floor we present the ‘Diversity of Parasites’ displaying various types of parasite specimens with accompanying educational movies,” write directors Midori Kamegai and Kazuo Ogawa. “The second floor exhibits are ‘Human and Zoonotic Parasites’ showing parasite life cycles and the symptoms they cause during human infection.”

Photo by Guilhem Vellut

We’ve here included a few choice pictures from the museum, but as Culture Trip’s India Irving warns, “the real-life specimens are far worse than the photographs; some of the displays present preserved parasites actually popping out of their animal hosts.”

She names as “the most repulsive item on view” a tapeworm “roughly the size of a London bus — it is the longest tapeworm in world and is exhibited alongside a rope of the same length so visitors can get a physical feel for just how enormous it actually was.” What other parasitological museum could hope to compete with that? Not that any have tried: the Meguro Parasitological Museum proudly describes itself as the only such institution in the world.

Photo by Guilhem Vellut

“Some of the displays are merely disturbing, while others are slightly more ghastly,” writes Mental Floss’ Jake Rossen. “If you’ve ever wanted to see a photo of a tropical bug prompting a human testicle to swell to the size of a gym bag, this is the place for you.” Like many other museums, it did shut down for a time earlier in the pandemic, but has been open again since June. (If you happen not to be a Japanese speaker, guides in English and other languages are available in both text and app form.) If current conditions have nevertheless kept Japan itself out of your reach, you can have a look at the Meguro Parasitological Museum’s unique offerings through this Flickr gallery — which gets many of us as close to these organisms as we care to be.

via Mental Floss

Related Content:

Discover the Japanese Museum Dedicated to Collecting Rocks That Look Like Human Faces

The First Museum Dedicated to Japanese Folklore Monsters Is Now Open

Take a Virtual Tour of the Mütter Museum and Its Many Anatomically Peculiar Exhibits

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.