What does it mean to describe something as relaxing?

Most of us would agree that a relaxing thing is one that quiets both mind and body.

There’s scientific evidence to support the stress-relieving, restorative effects of spending time in nature.

Even go-go-go city slickers with a hankering for excitement and adventure tend to understand the concept of “relaxing” as something slow-paced and surprise-free.

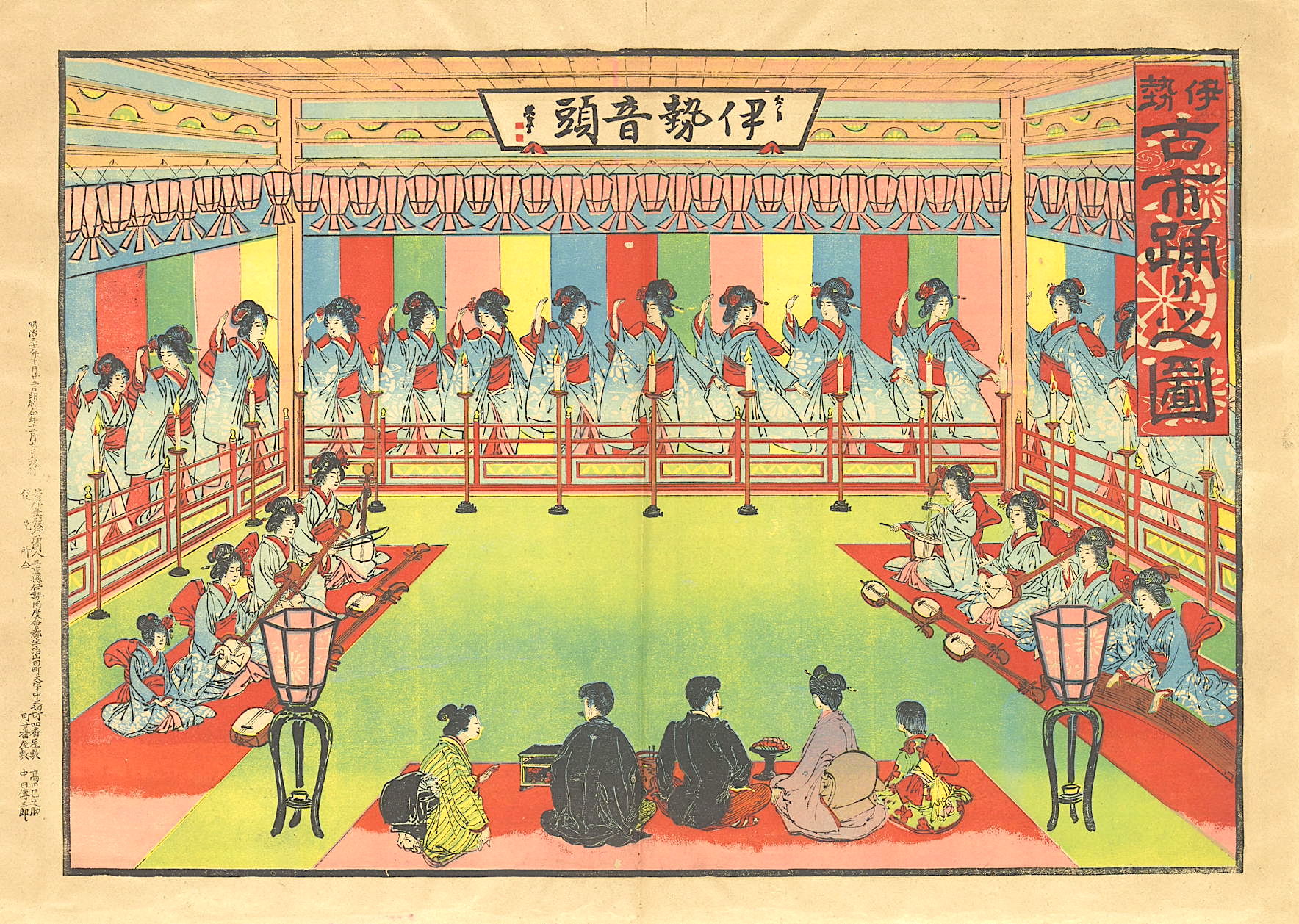

HBO Max is touting its collection of animation master Hayao Miyazaki’s films with 30 Minutes of Relaxing Visuals from Studio Ghibli, above.

Will all of us experience those 30 minutes as “relaxing”?

Maybe not.

Studio Ghibli fans may find themselves gripped by a sort of trivia contest competitiveness, shouting the names of the films that supply these pastoral visions—Ponyo! Grave of the Fireflies!! Howl’s Moving Castle!!!

Fledgling animators may feel as if they’ve swallowed a stone—no matter how hard I try, nothing I make will approach the beauty on display here.

Sticklers—and there are plenty leaving comments on YouTube—may be irritated to realize that it’s actually not 30 but 6 minutes of visuals, looped 5 times.

Insomniacs (such as this reporter) may wish there was more looping and less content. The selected scenery is tranquil enough, but the clips themselves are brief, leading to some jarring transitions.

(One possible workaround for those hoping to lull themselves to sleep: fiddle with the speed settings. Played at .25 and muted, this compilation becomes very relaxing, much like artist Douglas Gordon’s video installation, 24 Hour Psycho. Leave the sound up and the lapping waves, gentle winds, and chuffing trains turn into something worthy of a slasher flick.

Finally, with so much attention focussed on Mars these days, we can’t help imagining what alien life forms might make of these earthly visions—ahh, this green, sheep-dotted pasture does lower my stress level… wait, WTF was THAT!? Nothing on my home planet prepared me for the possibility of a monstrous winged house comprised of overgrown bagpipes and chicken legs lumbering through the countryside!

We concede that 30 Minutes of Relaxing Visuals from Studio Ghibli is a pleasant thing to have playing in the background as we wait for COVID restrictions to be lifted… but ultimately, you may find these 36 minutes of music from Studio Ghibli films more genuinely relaxing.

via Kottke

Related Content:

A Magical Look Inside the Painting Process of Studio Ghibli Artist Kazuo Oga

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.