Quick, name a melancholy Dane.

For most of us, the choice comes down to Hamlet or Hans Christian Andersen, author of such bittersweet tales as “The Little Match Girl,” “The Steadfast Tin Soldier,” and “The Little Mermaid.”

Andersen’s personal life remains a matter of both speculation and fascination.

Was he gay? Asexual? A virgin with a propensity for massive crushes on unattainable women, who engaged prostitutes solely for conversation?

No one can say for sure.

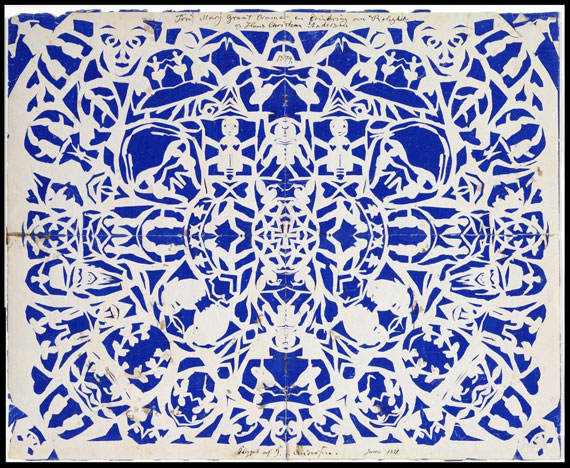

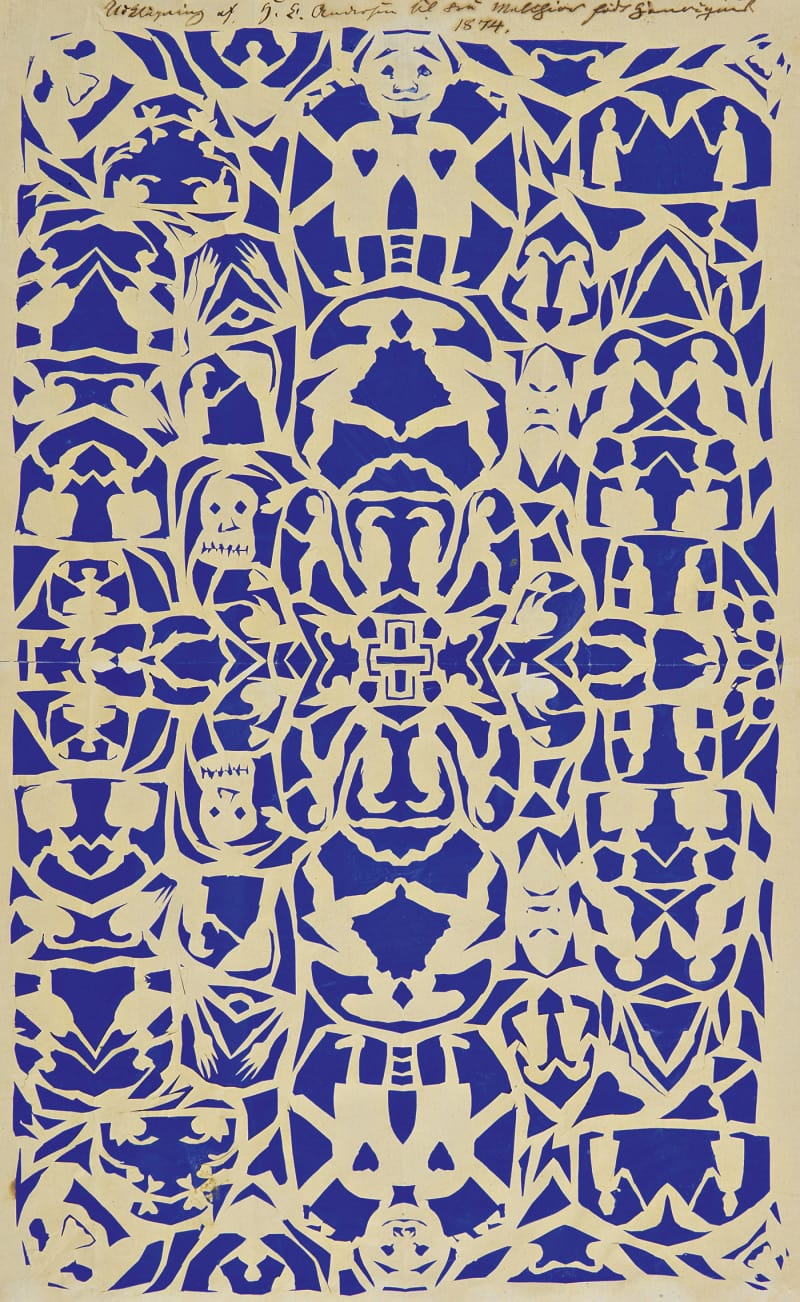

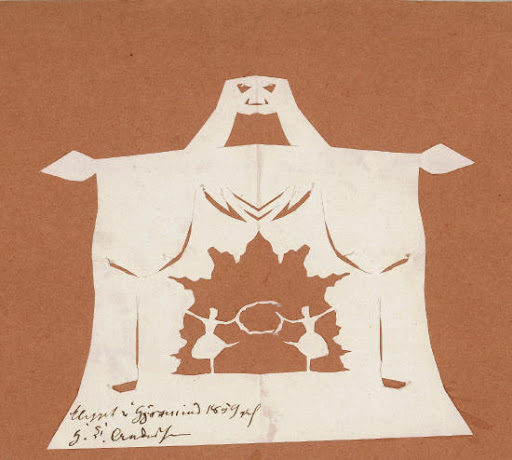

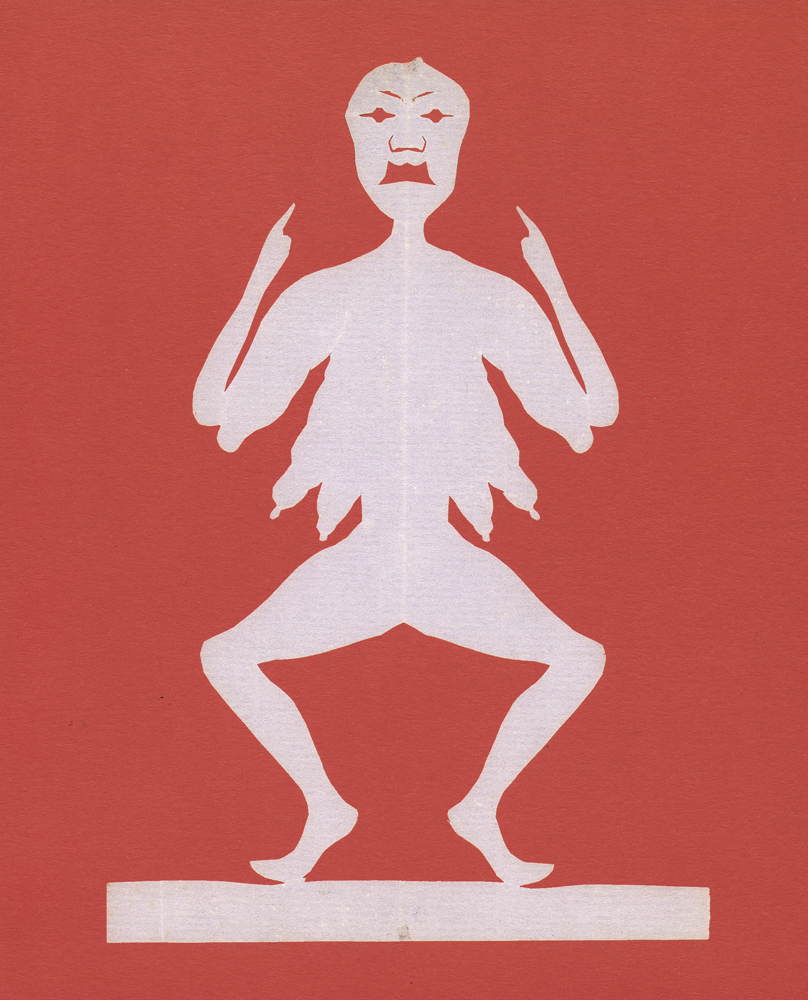

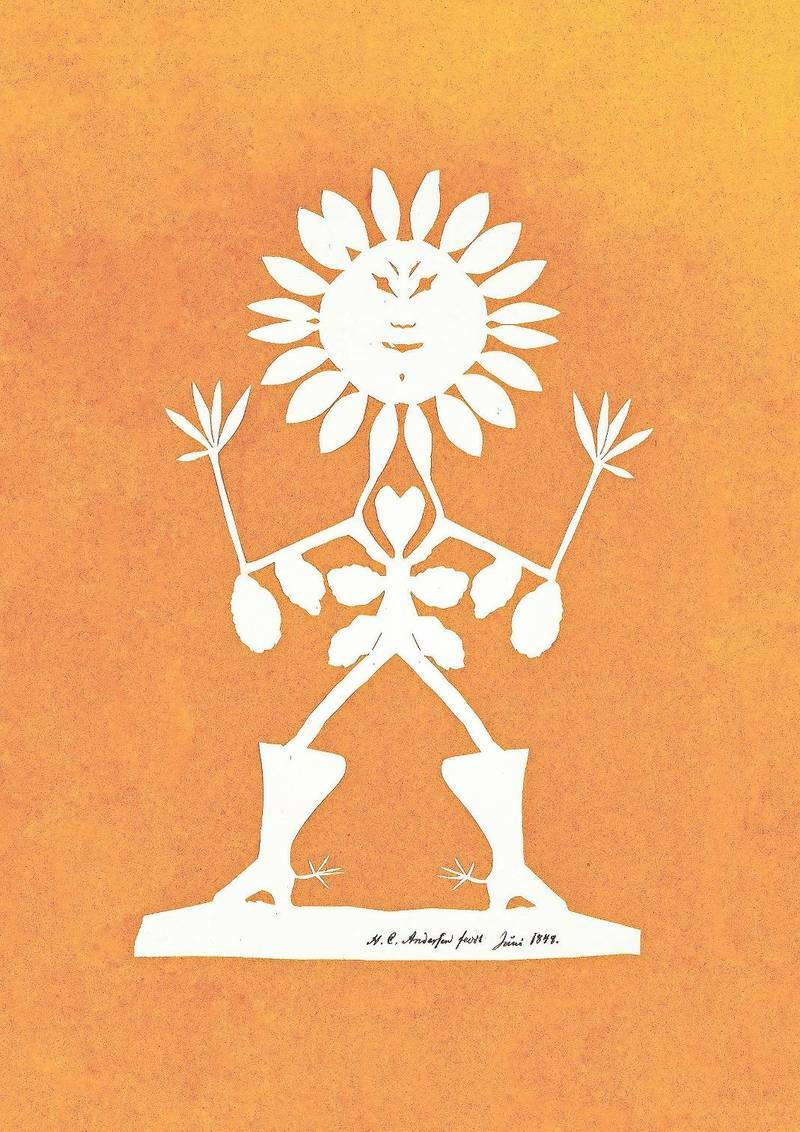

What we know definitively is that he was a jolly and talented paper cutter.

He enchanted party guests of all ages with improvised stories as he snipped away, unfolding the sheet at tale’s end, a souvenir for some lucky young listener.

“You can imagine how many of them must have got torn or creased,” says art historian Detlef Klein, who co-curated the 2018 exhibition Hans Christian Andersen, Poet with Pen and Scissors. “You could often bend the figures a little, blow at them and then move them across the tabletop.”

Amazingly, 400 some survive, primarily in the Odense City Museums’ large collection.

Pierrots, dancers, and swans were frequent subjects. Spraddle-legged creature’s bellies served as proscenium theaters. Even the simplest feature some tricky, spindly bits—tightropes, umbrellas, delicate shoes.…

The most intricate pieces, like Fantasy Cutting for Dorothea Melchior below, were thoughtful homemade presents for close friends. (The Melchiors hosted Andersen’s 70th birthday party and he died during an extended visit to their country home.)

The cuttings bring fairy tales to mind, but they are not specific to the published work of Andersen. No Thumbelina. No Ugly Duckling. Not a mermaid in sight.

As Moy McCrory, senior lecturer in creative writing at the University of Derby, writes:

Andersen knew that his written work would outlast him: he was famous and successful, as were his tales. Yet he continued to work in these transient materials, their cheapness and availability making them of no value apart from their appeal to sentiment…Why work in a form that ought to have left no traces? I suggest that this showed how Andersen reacted to his fame, and to his own sense of being forever on the margins of the lived life. He moved amongst the educated and the famous, was friendly with Dickens, was patronized by nobles, but was outside those circles. His education was gained at some pains to himself, years after the usual dates for these activities (he would not even pass nowadays as a “mature student”, since his completion of elementary school only took place when he was a young adult). He was always placed outside the normal bounds of the society he kept.

Readers, we challenge you to play Pygmalion and release a fairy tale based on the images below.

All images, with the exception of The Royal Library Copenhagen’s The Botanist, directly above, are used with the permission of Odense City Museums, in accordance with a Creative Commons License.

Explore the Odense City Museums’ collection of Hans Christian Andersen’s papercuts here.

Bonus reading for those in need of a laugh: “The Saddest Endings of Hans Christian Andersen Stories” by the Toast’s Daniel M. Lavery.

Related Content:

Watch Animations of Oscar Wilde’s Children’s Stories “The Happy Prince” and “The Selfish Giant”

Enter an Archive of 6,000 Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized and Free to Read Online

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.