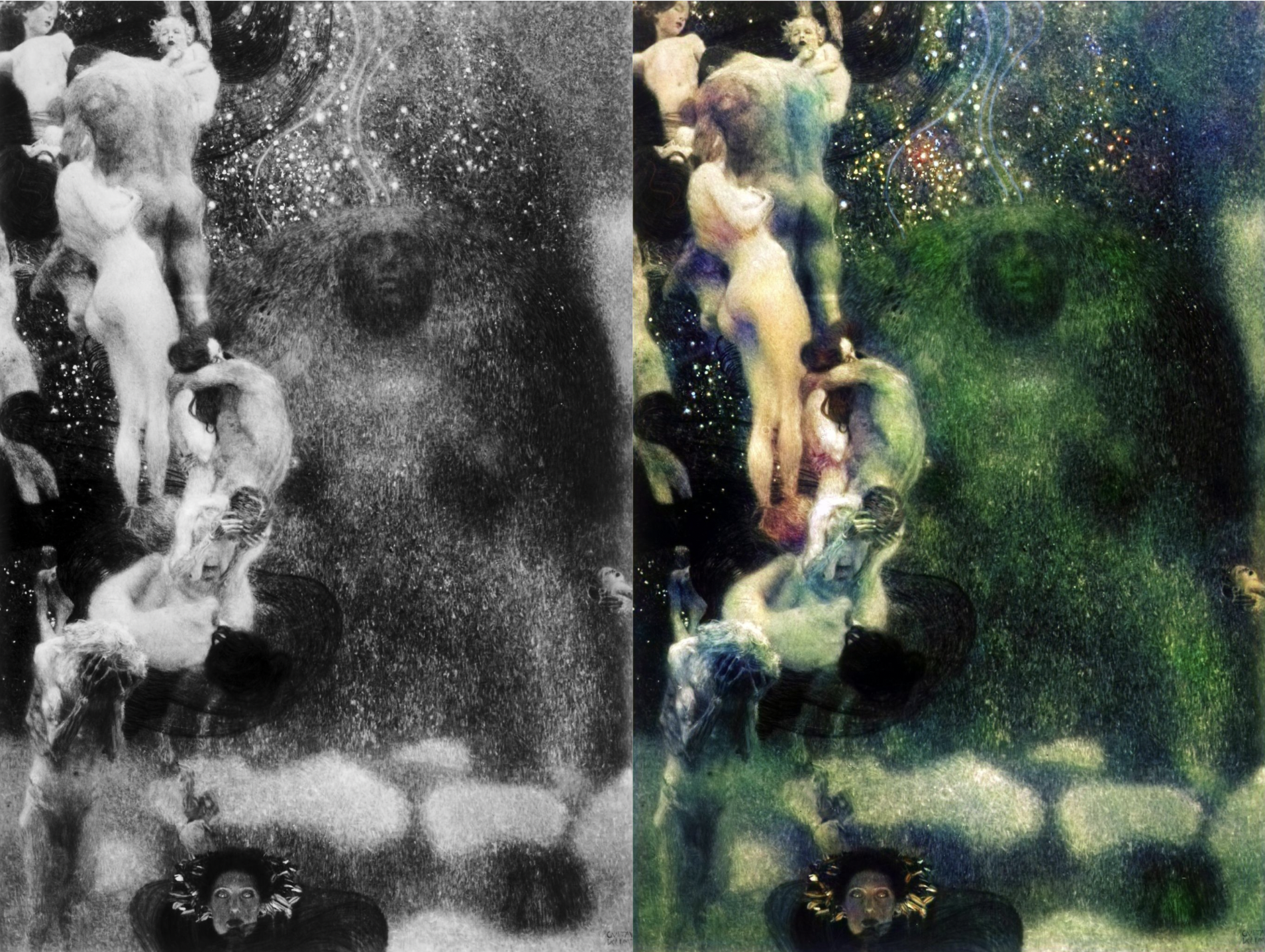

A century after the death of Gustav Klimt, his art continues to enrapture its viewers. Maybe it has enraptured you, but no matter how deep you’ve gone into Klimt’s oeuvre, there are three paintings you’ve only ever seen in black and white. That’s not because he painted them in that way; rich and brilliant colors originally figured into all his work, the most notable usage being the real gold layered onto his best-known painting, 1908’s The Kiss. In the year before The Kiss, he completed an even more ambitious work: a series of paintings commissioned for the University of Vienna’s Great Hall, meant to represent the fields after which they were titled: Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence.

Klimt’s “Faculty Paintings,” as they’re now known, struck critics at the time as pieces of “perverted excess.” Such charges must have been nothing new to Klimt, for whom unabashed eroticism and subjective views of reality — neither particularly in fashion in the institutions of early 20th-century Vienna — constituted basic artistic principles.

Ultimately, Klimt himself bought Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence back, and by the end of the Second World War all three had found their way into the hands of the Nazis. With defeat looming, they chose to burn down rather than surrender the Austrian castle in which they’d been storing the Faculty Paintings and other works of art.

With the Faculty Paintings surviving only in black-and-white photographs and scanty descriptions, generations of Klimt enthusiasts have had to imagine how they really looked. Now, Google Arts & Culture and Vienna’s Belvedere Museum have joined forces to figure out to a greater degree of certainty than ever, using artificial intelligence to determine what colors Klimt would have applied to Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence based on in-depth analyses of the rest of his work. You can get an overview of the process from the short video at the top of the post, and you can read about it in more detail at Google Arts & Culture.

“Klimt’s three Faculty Paintings were among the largest artworks Klimt ever created and in the field of Symbolist painting they represent Klimt’s masterpieces,” says Belvedere curator Dr. Franz Smola in a Google Arts & Culture blog post. “The colors were essential for the overwhelming effect of these paintings, and they caused quite a stir among Klimt’s contemporaries. Therefore the reconstruction of the colors is synonymous with recognizing the true value and significance of these outstanding artworks.” The project comes as just one part of Klimt vs. Klimt: The Man of Contradictions, an online retrospective featuring more than 120 of the artist’s works available to view in augmented reality, as well as an ultra-high-resolution scan of The Kiss. Klimt’s paintings may no longer shock us, but they still have much to show us.

Related Content:

The Long-Lost Pieces of Rembrandt’s Night Watch Get Reconstructed with Artificial Intelligence

AI & X‑Rays Recover Lost Artworks Underneath Paintings by Picasso & Modigliani

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.