I HAVE endeavoured in this Ghostly little book, to raise the Ghost of an Idea, which shall not put my readers out of humour with themselves, with each other, with the season, or with me. May it haunt their houses pleasantly, and no one wish to lay it. — Charles Dickens

Some twenty years before Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas, another animated entertainment injected “the most wonderful time of the year” with a potent dose of horror.

Surely I’m not the only child of the 70s to have been equal parts mesmerized and stricken by director Richard Williams’ faithful, if highly condensed, interpretation of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

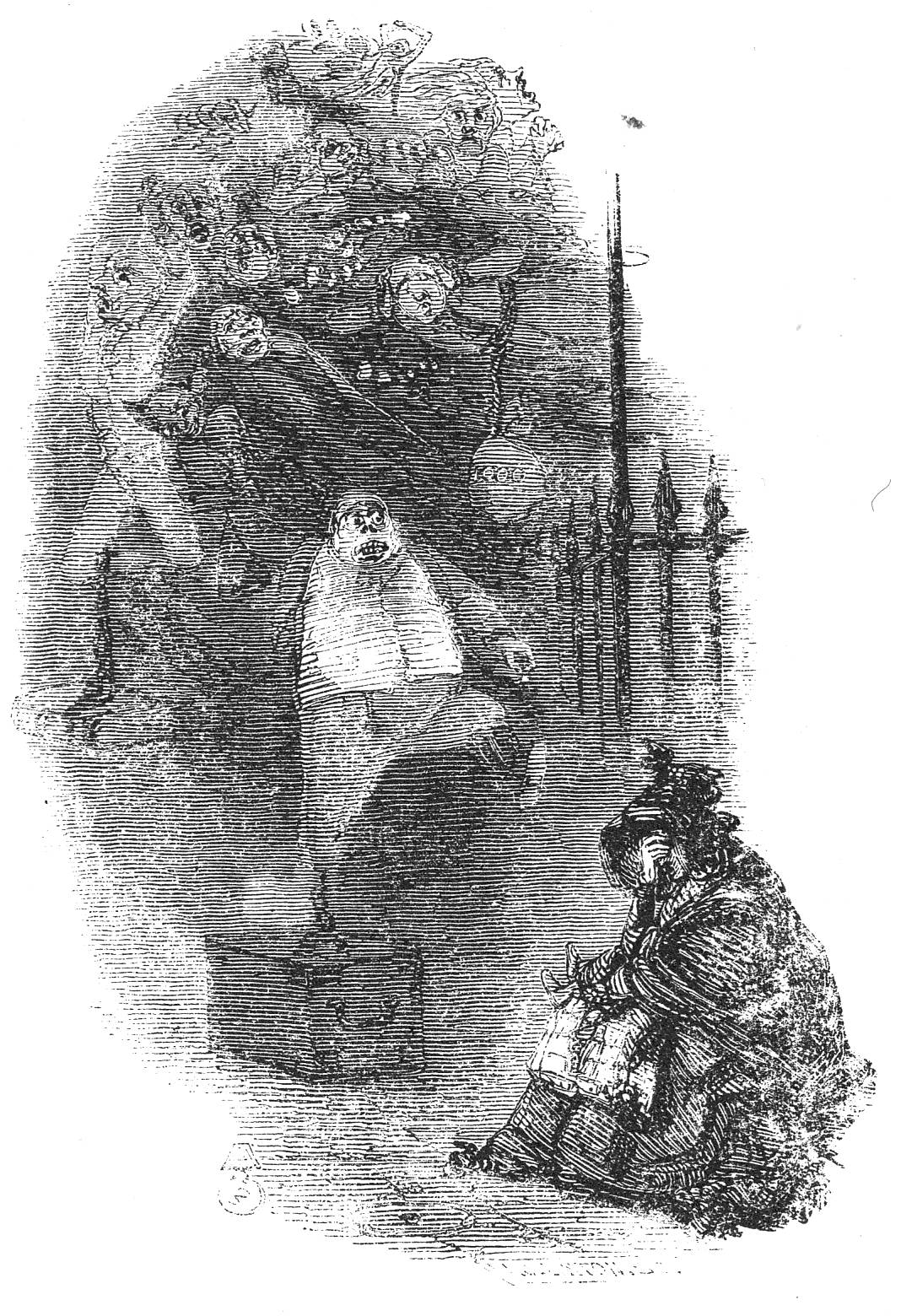

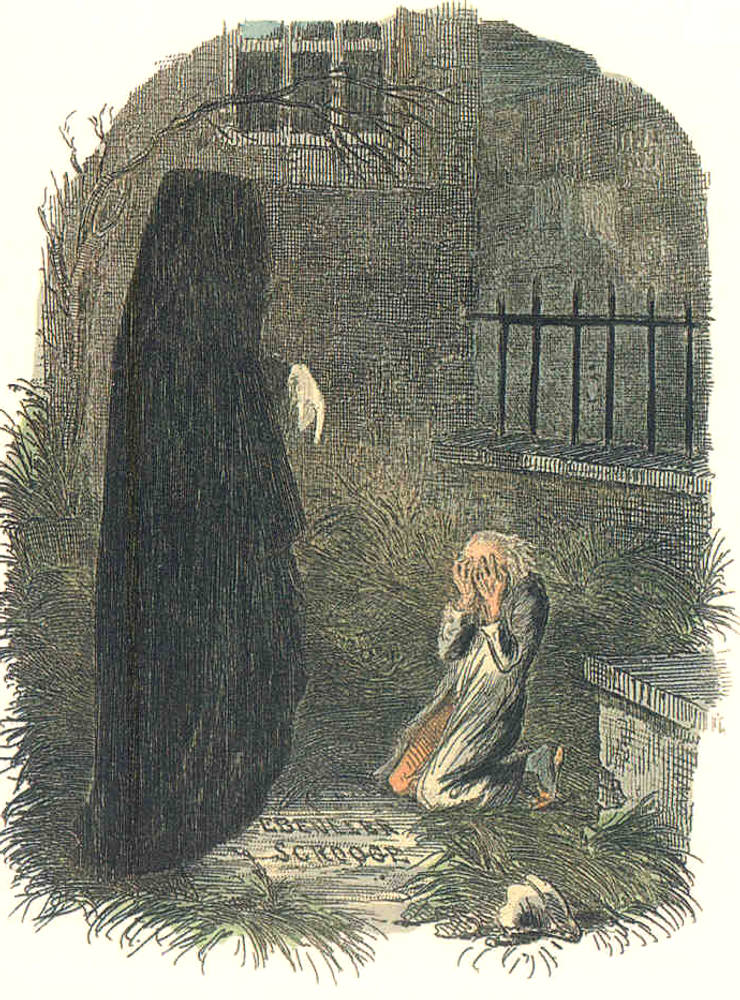

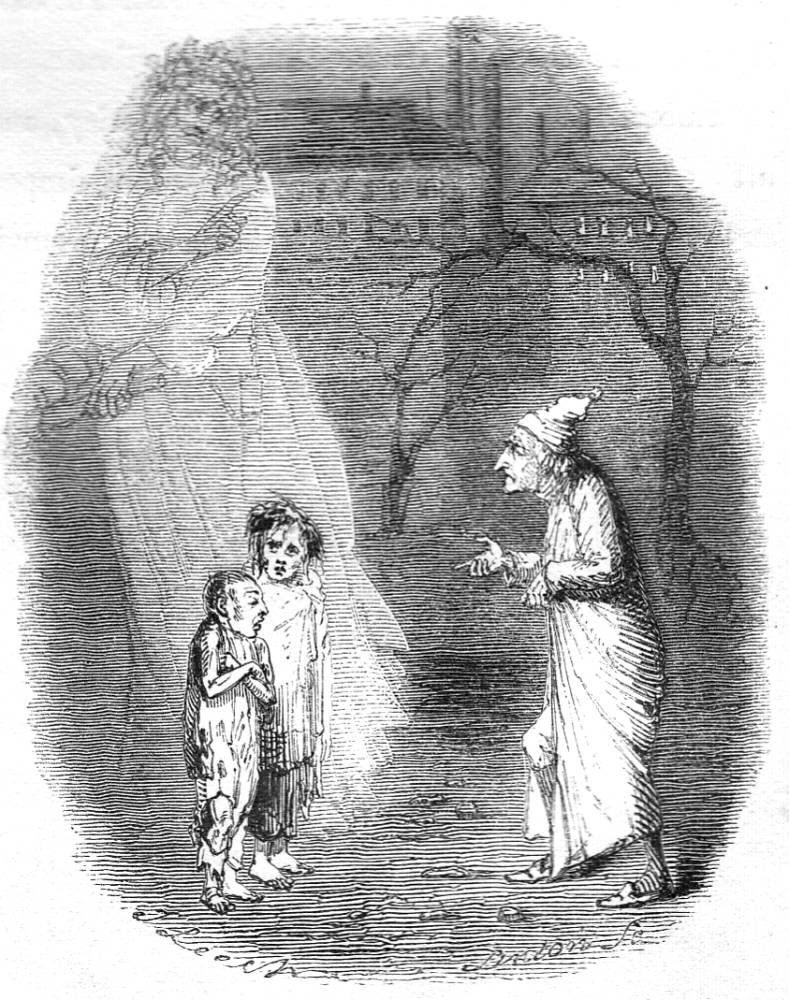

The 25-minute short features a host of hair-raising images drawn directly from Dickens’ text, from a spectral hearse in Scrooge’s hallway and the Ghost of Marley’s gaping maw, to a night sky populated with miserable, howling phantoms and the monstrous children lurking beneath the Ghost of Christmas Present’s skirts:

Yellow, meagre, ragged, scowling, wolfish; but prostrate, too, in their humility. Where graceful youth should have filled their features out, and touched them with its freshest tints, a stale and shrivelled hand, like that of age, had pinched, and twisted them, and pulled them into shreds. Where angels might have sat enthroned, devils lurked, and glared out menacing. No change, no degradation, no perversion of humanity, in any grade, through all the mysteries of wonderful creation, has monsters half so horrible and dread… This boy is Ignorance. This girl is Want. Beware them both, and all of their degree, but most of all beware this boy, for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased.

Producer Chuck Jones, whose earlier animated holiday special, Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, is in keeping with his classic work on Bugs Bunny and other Warner Bros. faves, insisted that this cartoon should mirror the look of the John Leech steel engravings illustrating Dickens’ 1843 original.

D.T. Nethery, a former Disney animation artist and fan of this Christmas Carol explains that the desired Victorian look was achieved with a labor-intensive process that involved drawing directly on cels with Mars Omnichrom grease pencil, then painting the backs and photographing them against detailed watercolored backgrounds.

As director Williams recalls below, he and a team including master animators Ken Harris and Abe Levitow were racing against an impossibly tight deadline that left them pulling 14-hour days and 7‑day work weeks. Reportedly, the final version was completed with just an hour to spare. (“We slept under our desks for this thing.”)

As Michael Lyons observes in Animation Scoop, the exhausted animators went above and beyond with Jones’ request for a pan over London’s rooftops, “making the entire twenty-five minutes of the short film take on the appearance of art work that has come to life”:

…there are scenes that seem to involve camera pans, or sequences in which the camera seemingly circles around the characters. Much of this involved not just animating the characters, but the backgrounds as well and in different sizes as they move toward and away from the frame. The hand-crafted quality, coupled with a three-dimensional feel in these moments, is downright tactile.

Revered British character actors Alistair Sim (Scrooge) and Michael Hordern (Marley’s Ghost) lent some extra class, reprising their roles from the evergreen, black-and-white 1951 adaptation.

The short’s television premiere caused such a sensation that it was given a subsequent theatrical release, putting it in the running for an Oscar for Best Animated Short Subject. (It won, beating out Tup-Tup from Croatia and the NSFW-ish Kama Sutra Rides Again which Stanley Kubrick had handpicked to play before A Clockwork Orange in the UK.)

With theaters in Dallas, Los Angeles, Portland, Providence, Tallahassee and Vancouver cancelling planned live productions of A Christmas Carol out of concern for the public health during this latest wave of the pandemic, we’re happy to get our Dickensian fix, snuggled up on the couch with this animated 50-year-old artifact of our childhood.…

Related Content:

Hear Neil Gaiman Read A Christmas Carol Just as Dickens Read It

Charles Dickens’ Hand-Edited Copy of His Classic Holiday Tale, A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol, A Vintage Radio Broadcast by Orson Welles (1939)

Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primaologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.