Back in the late 80s, there was a rumor floating around that Earth Girls Are Easy.

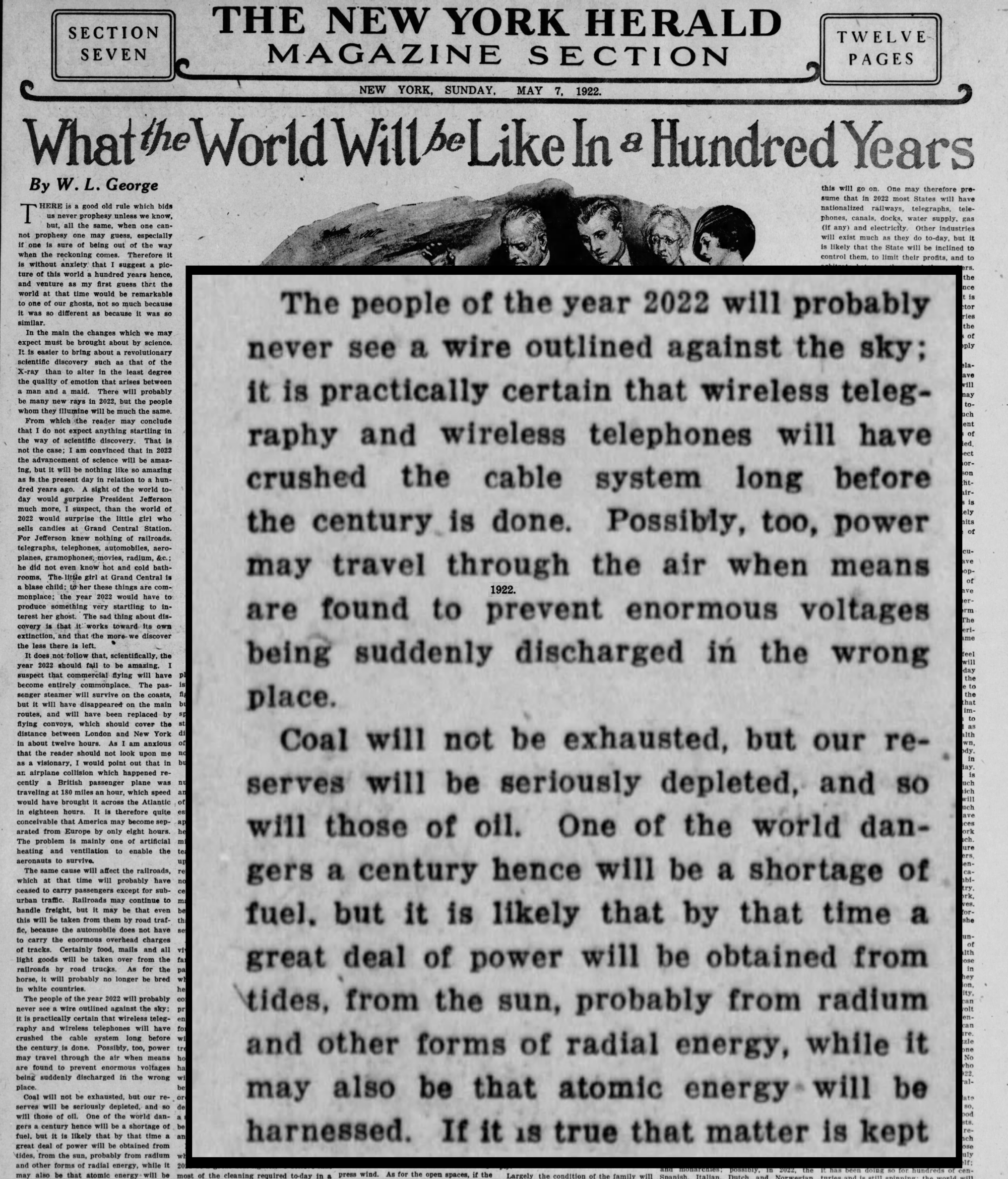

40 some years of scientific and social advancement have shifted the conversational focus.

We’re just now beginning to understand that Space Sex is Serious Business.

Particularly if SpaceX CEO Elon Musk achieves his goal of establishing a permanent human presence on Mars.

Surely at some point in their long travels to and residence on Mars, those pioneers would get down to business in much the same way that rats, fruit flies, parasitic wasps, and Japanese rice fish have while under observation on prior space expeditions.

Meanwhile, we’re seriously lacking in human data.

A pair of human astronauts, Jan Davis and Mark Lee, made history in 1992 as the first married couple to enter space together, but NASA insisted their relations remained strictly professional for the duration, and that a shuttle’s crew compartment is too small for the sort of antics a nasty-minded public kept asking about.

In an interview with Mens Health, Colonel Mike Mullane, a veteran of three space missions, confirmed that a spacecraft’s layout doesn’t favor romance:

The only privacy would have been in the air lock, but everybody would know what you were doing. You’re not out there doing a spacewalk. There’s no reason to be in there.

Shortly after Davis and Lee returned to earth, NASA formalized an unspoken rule prohibiting husbands and wives from venturing into space together. It did little to squelch public interest in space sex.

One wonders if NASA’s rule has been rewritten in accordance with the times. Air lock aside, might same sex couples remain free to swing what hetero-normative marrieds (arguably) cannot?

This is but one of hundreds of space sex questions begging further consideration.

Some of the most serious are raised in Tom McCarten’s witty collage animation for FiveThirtyEight, above.

Namely how damaging will cosmic radiation and microgravity prove to human reproduction? As more humans toy with the possibility of leaving Earth, this question feels less and less hypothetical.

Maggie Koerth-Baker, who researched and narrates the animated short, notes that Musk portrayed the risks of radiation as minor during a presentation at the 67th International Astronautical Congress in Guadalajara, Mexico, and breathed not a peep as to the effects of microgravity.

Yet scientific studies of non-human space travelers document a host of reproductive issues including lowered libido, atypical hormone levels, ovulatory dysfunction, miscarriages, and fetal mutations.

On its webpage, NASA provides some information about the Reproduction, Development, and Sex Differences Laboratory of its Space Biosciences Research Branch, but remains mum on topics of pressing concern to, say, students in a typical middle school sex ed class.

Like achieving and maintaining erections in microgravity.

In Physiology News Magazine, Dr. Adam Watkins, associate professor of Reproductive and Developmental Physiology at the University of Nottingham, suggests that internal and external atmospheric changes would make such things, pardon the pun, hard:

Firstly, just staying in close contact with each other under zero gravity is hard. Secondly, as astronauts experience lower blood pressure while in space, maintaining erections and arousal are more problematic than here on Earth.

The exceptionally forthright Col Mullane has some contradictory first hand experience that should come as a relief to all humankind:

A couple of times, I would wake up from sleep periods and I had a boner that I could have drilled through kryptonite.

Related Content

Free Online Astronomy Courses

Watch Family Planning, Walt Disney’s 1967 Sex Ed Production, Starring Donald Duck

The Story Of Menstruation: Watch Walt Disney’s Sex Ed Film from 1946

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.