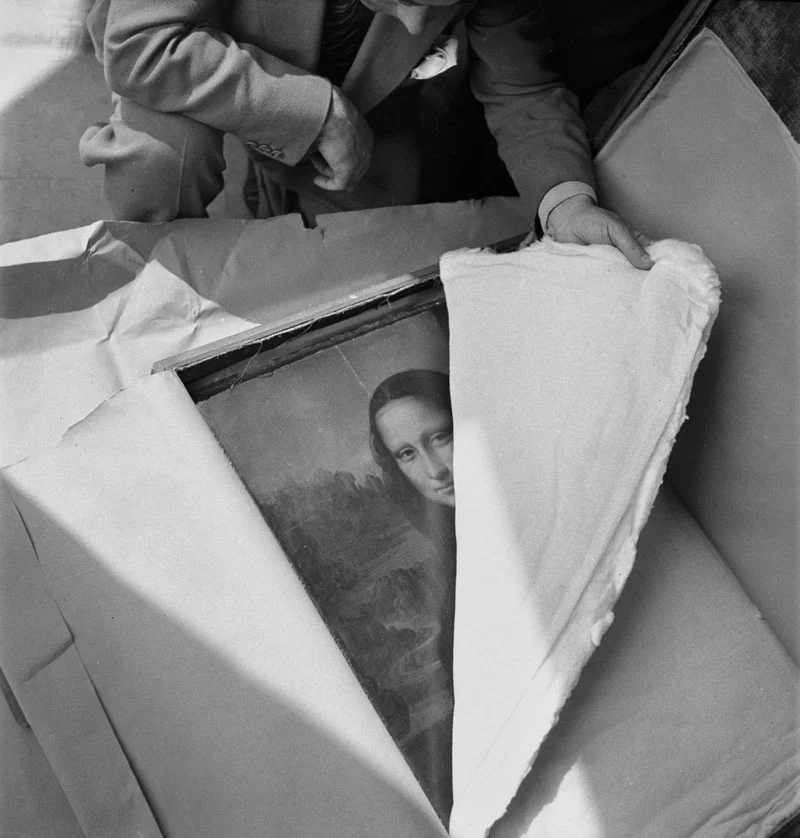

Photograph by Pierre Jahan/Archives des museés nationaux

Twice, we’ve brought you posts explaining how the Mona Lisa – the most famous painting in the world – went from near obscurity to global notoriety almost overnight, after an employee of the Louvre purloined and tried to hide it in 1911. Accusations flew – including very public accusations against Pablo Picasso; salacious rumors circulated; the enigmatic smile of Lisa del Gioconda — the Florentine silk merchant’s wife depicted in the painting – appeared in black and white photographs in newspapers around the globe. When she returned to the museum, visitors couldn’t, and still cannot, wait to see her in person. As great as that story is, what happened a few decades later under the Nazi-controlled Vichy government makes for an even better tale.

By the 1930s, the Mona Lisa was deemed the most important work of art in France’s most important museum. With due respect to the Monuments Men (and unsung Monuments Women), before the Allies arrived to rescue many of Europe’s priceless works of art, French civil servants, students, and workmen did it themselves, saving most of the Louvre’s entire collection. The hero of the story, Jacques Jaujard, director of France’s National Museums, has gone down in history as “the man who saved the Louvre” — also the title of an award-winning French documentary (see trailer below). Mental Floss provides context for Jaujard’s heroism:

After Germany annexed Austria in March of 1938, Jaujard… lost whatever small hope he had that war might be avoided. He knew Britain’s policy of appeasement wasn’t going to keep the Nazi wolf from the door, and an invasion of France was sure to bring destruction of cultural treasures via bombings, looting, and wholesale theft. So, together with the Louvre’s curator of paintings René Huyghe, Jaujard crafted a secret plan to evacuate almost all of the Louvre’s art, which included 3600 paintings alone.

On the day Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Nonaggression Pact, August 25, 1939, Jaujard closed the Louvre for “repairs” for three days while staff, “students from the École du Louvre, and workers form the Grands Magazines du Louvre department store took paintings out of their frames… and moved statues and other objects from their displays with wooden crates.”

The statues included the three ton Winged Nike of Samothrace (see a photo of its move here), the Egyptian Old Kingdom Seated Scribe, and the Venus de Milo. All of these, like the other works of art, would be moved to chateaus in the countryside for safe keeping. On August 28, “hundreds of trucks organized into convoys carried 1000 crates of ancient and 268 crates of paintings and more” into the Loire Valley.

Included in that haul of treasures was the Mona Lisa, placed in a custom case, cushioned with velvet. Where other works received labels of yellow, green, and red dots according to their level of importance, the Mona Lisa was marked with three red dots — the only work to receive such high priority. It was transported by ambulance, gently strapped to a stretcher. After leaving the museum, the painting would be moved five times, “including to Loire Valley castles and a quiet abbey.” The Nazis would loot much of what was left in the Louvre, and force it to re-open in 1940 with most of its galleries starkly empty. But the Mona Lisa — at the top of Hitler’s list of artworks to expropriate — remained safe, as did many thousands more artworks Jaujard believed were the “heritage of all humanity,” as Inge Laino, Paris Muse Director, says in the France 24 segment above.

Related Content:

How Did the Mona Lisa Become the World’s Most Famous Painting?: It’s Not What You Think

The Louvre’s Entire Collection Goes Online: View and Download 480,00 Works of Art

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness