Throughout history, determined artists have worked on available surfaces — scrap wood, cardboard, walls…

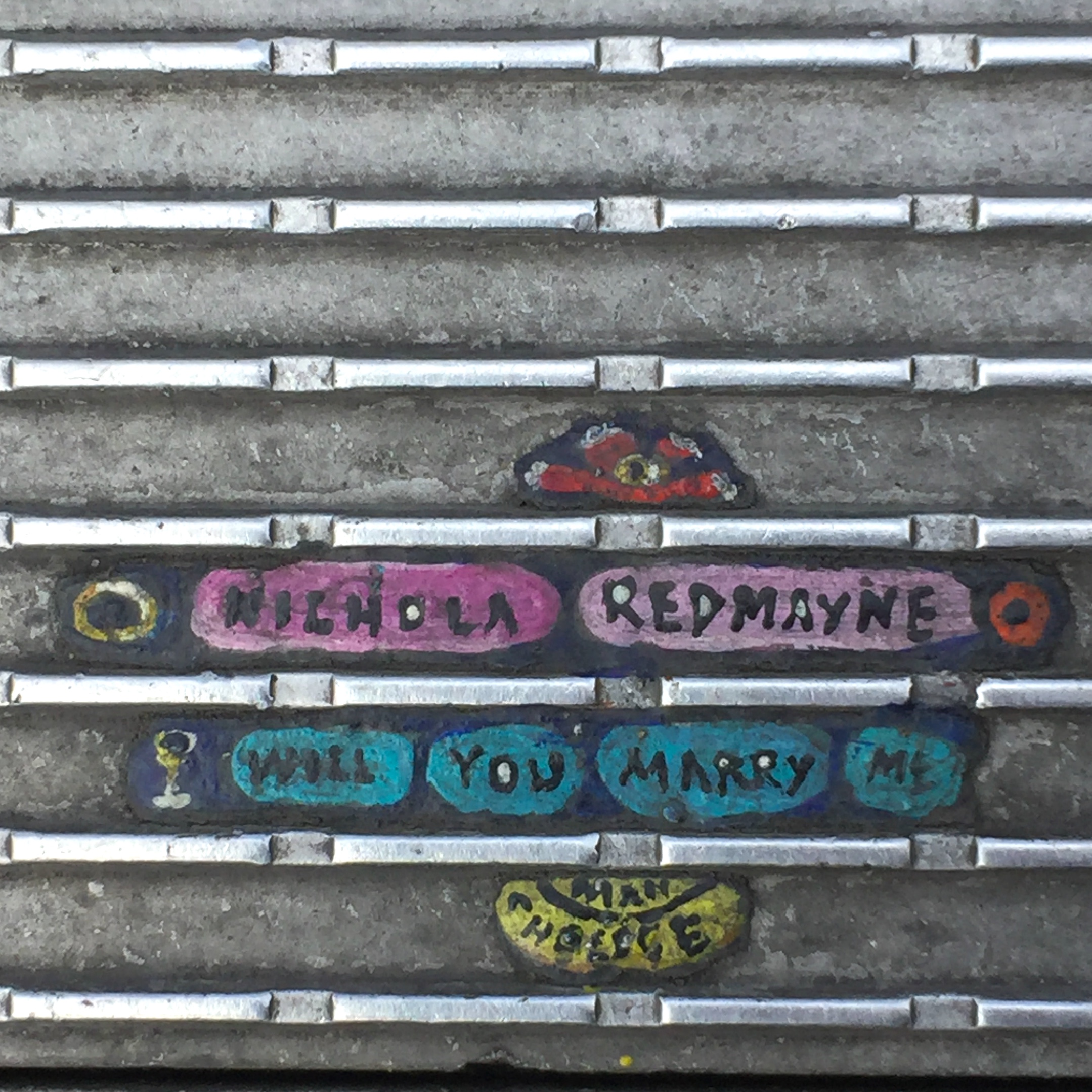

Ben Wilson has created thousands of works using chewing gum as his canvas.

Specifically, chewing gum spat out by careless strangers.

His work has become a defining featuring of London’s Millennium Bridge, a modern structure spanning the Thames, and connecting such South Bank attractions as Tate Modern and the Shakespeare’s Globe with St. Paul’s Cathedral to the north.

A 2021 profile in The Guardian documents the creation process:

The technique is very precise. He first softens the oval of flattened gum a little with a blowtorch, sprays it with lacquer and then applies three coats of acrylic enamel, usually to a design from his latest book of requests that come from people who stop and crouch and talk. He uses tiny modelers’ brushes, quick-drying his work with a lighter flame as he goes along, and then seals it with more lacquer. Each painting takes a few hours and can last for many years.

Unsurprisingly, Wilson works very, very small.

For every Millennium Bridge pedestrian who’s hip to the ever-evolving solo exhibition underfoot, there are several hundred who remain completely oblivious.

Stoop to admire a miniature portrait, abstract, or commemorative work, and the bulk of your fellow pedestrians will give you a wide berth, though every now and then a concerned or curious party will stop to see what the deal is.

Wilson, who works sprawled on the bridge’s metal treads, his nose close to touching his tiny, untraditional canvas, receives a similar response, as described in Zachary Denman’s short documentary, Chewing Gum Man:

They make think I’ve fallen over and they may think I’ve had a cardiac arrest or something, so I’ve had lots of ambulances turning up…I’ve had loads of police.

His subjects are suggested by the shape of the spat out gum, by friends, by strangers who stop to watch him work:

I’ve had to deal with people memorializing people who have been murdered. People who have been so lonely, or remembering favorite pets; people who are destitute in all sorts of ways. It goes from proposal pictures, ‘Will you marry me?’, to people who I drew when they were kids and they now have their own kids.

Like any street artist, Wilson’s had his share of run ins with the law, including a wrongful 2010 arrest for criminal damage, when a crowd of schoolchildren who’d been enthusiastically watching an itty bitty St. Pauls taking shape on a blob of gum witnessed him being dragged off by his feet. (He asked if he could finish the picture first…)

He may not get permission to create the public works he goes out daily to create, but he contributes by clearing the area of litter, and as he points out, painting on discarded gum doesn’t constitute defacing anyone’s actual property:

Technically in one sense, I’m working within the law …if I paint on chewing gum, it’s like finding No Man’s Land or common ground. It’s a space which is not under the jurisdiction of a local or national government.

See more of Ben Wilson’s work in his online Gum Gallery.

Photos in this article taken by Ayun Halliday, 2022. All rights reserved.

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.