“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing,” a Quote Falsely Attributed to Edmund Burke

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” It’s a quote routinely attributed to Edmund Burke. But it turns out falsely so. Apparently, he never uttered these words. At best, the essence of the quote can be traced back to the utilitarian philosopher John Stuart Mill, who delivered an 1867 inaugural address at the University of St. Andrews and stated: “Let not any one pacify his conscience by the delusion that he can do no harm if he takes no part, and forms no opinion. Bad men need nothing more to compass their ends, than that good men should look on and do nothing. He is not a good man who, without a protest, allows wrong to be committed in his name, and with the means which he helps to supply, because he will not trouble himself to use his mind on the subject.”

If you came to this page looking for Burke to help support ideas of social upheaval, we’d suggest watching the video below, or better yet reading Reflections on the Revolution in France, a fundamental text in the canon of conservative literature where Burke cautioned against abrupt or violent social change.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

1,700 Free Online Courses from Top UniversitiesJeremy Bentham’s Mummified Body Is Still on Display–Much Like Other Aging British Rock Stars

Read More...The Aesthetic of Evil: A Video Essay Explores Evil in the Films of Bergman, Hitchcock, Kubrick, Scorsese & Beyond

Movies have heroes and villains. Or at least children’s movies do; the more sophisticated the audience, the hazier the line between good and evil becomes, until it finally seems to vanish altogether. Not that cinema directed toward genuinely mature audiences dispenses with those concepts entirely: rather, it makes art out of the ambiguity and interpenetration between them. This is true, to an extent, even in some of the recent wave of big-budget superhero movies, in the main exercises in rolling an “adult” texture onto stories essentially geared toward adolescents. Hence the appearance of the Joker, Batman’s grinning arch-nemesis, in “The Aesthetic of Evil,” the Cinema Cartography video essay above.

In the Joker of Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, “we see an evil that’s relentless, primarily because the core function is complete and total anarchy. Whatever order is established, whoever it’s under ‚must be destroyed. As a result, an epoch is created where any rules or codes of conduct are broken. Anything that you anticipate will happen, will result in the opposite.”

This Joker made an outsized cultural impact with not just the explicitness of his disorder-oriented morality, but also a material-transcending performance by Heath Ledger. In that same era, Jamie Hector took a comparatively minimalist but equally memorable turn in David Simon’s series The Wire as Marlo Stanfield, a drug kingpin “too villainous for the villains.” Like the Joker, Marlo is a law unto himself, “willing to destroy the equilibrium of any facet of the world there is, on a whim.”

These two represent just one of the forms evil has taken in recent decades. The essay’s other examples range from Psycho’s Norman Bates and 2001’s HAL 9000 to The King of Comedy’s Rupert Pupkin and Fanny and Alexander’s stepfather Edvard — or rather, the unwelcome transformation of the family Edvard represents. The most diabolical evil does not confine itself within the person of the antagonist, especially not in the work of Michael Haneke, which twice appears in “The Aesthetic of Evil.” Benny’s Video is on one level about a murderous adolescent; on another, it’s about the “evasion of the real” that seduces us all. The White Ribbon is on one level about random acts of violence in a small village; on another, it’s about how evil reflects “the collective consciousness of a society.” Haneke’s films have often been described as difficult to watch, and that may well have less to do with what they show than what they know: even if we aren’t all villains, we’re certainly not heroes.

Related Content:

Orson Welles on the Art of Acting: ‘There is a Villain in Each of Us’

Rare Video: Georges Bataille Talks About Literature & Evil in His Only TV Interview (1958)

The Aesthetic of Anime: A New Video Essay Explores a Rich Tradition of Japanese Animation

The Dark Knight: Anatomy of a Flawed Action Scene

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...A Brief History of Making Deals with the Devil: Niccolò Paganini, Robert Johnson, Jimmy Page & More

When the term “witch hunt” gets thrown around in cases of powerful men accused of harassment and abuse, historians everywhere bang their heads against their desks. The history of persecuting witches—as every schoolboy and girl knows from the famous Salem Trials—involves accusations moving decidedly in the other direction.

But we’re very familiar with men supposedly selling out to Satan, dealing—or just dueling—with the devil. They weren’t called witches for doing so, or burned at the stake. They were blues pioneers, virtuoso fiddlers, and guitar gods. From the devilishly dashing Niccolò Paganini, to Robert Johnson at the Crossroads, to Jimmy Page’s black magic, to “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” to the omnipresence of Satan in metal…. The devil “seems to have quite the interest in music,” notes the Polyphonic video above.

Before musicians came to terms with the dark lord, power-hungry scholars used demonology to summon Luciferian emissaries like Mephistopheles. The legend of Faust dates back to the late 16th century and a historical alchemist named Johann Georg Faust, who inspired many dramatic works, like Christopher Marlowe’s The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, Johann Goethe’s Faust, Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus, Mikhail Bugakov’s The Master and Margarita, and F.W. Murnau’s 1926 silent film.

The Faust legend may be the sturdiest of such stories, but it is not by any means the origin of the idea. Medieval Catholic saints feared the devil’s enticements constantly. Medieval occultists often saw things differently. If we can trace the notion of women consorting with the devil to the Biblical Eve in the Garden, we find male analogues in the New Testament—Christ’s temptations in the desert, Judas’s thirty pieces of silver, the possessed vagrant who sends his demons into a herd of pigs. But we might even say that God made the first deal with the devil, in the opening wager of the book of Job.

In most examples—Charlie Daniels’ triumphal folk tale aside—the deal usually goes down badly for the mortal party involved, as it did for Robert Johnson when the devil came for his due, and convened the morbidly fascinating 27 Club. Goethe imposes a redemptive happy ending onto Faust that seems to wildly overcompensate for the typical fate of souls in hell’s pawn shop. Kierkegaard took the idea seriously as a cultural myth, and wrote in Either/Or that “every notable historical era will have its own Faust.”

Modern-day Fausts in the popular genre of the day, the conspiracy theory, are famous entertainers, as you can see in the unintentionally humorous supercut above from a YouTube channel called “EndTimeChristian.” As it happens in these kinds of narratives, the cultural trope gets taken far too literally as a real event. The Faust legend shows us that making deals with the devil has been a literary device for hundreds of years, passing into popular culture, then the blues—a genre haunted by hell hounds and infernal crossroads—and its progeny in rock and roll and hip hop.

Those who talk of selling their souls might really believe it, but they inherited the language from centuries of Western cultural and religious tradition. Selling one’s soul is a common metaphor for living a carnal life, or getting into bed with shady characters for worldly success. But it’s also a playful notion. (A misunderstood aspect of so much metal is its comic Satanic overkill.) Johnson himself turned the story of selling his soul into an iconic boast, in “Crossroads” and “Me and the Devil Blues.” “Hello Satan,” he says in the latter tune, “I believe it’s time to go.”

Chilling in hindsight, the line is the bluesman’s grimly casual acknowledgment of how life on the edge would catch up to him. But it was worth it, he also suggests, to become a legend in his own time. In the short, animated video above from Music Matters, Johnson meets the horned one, a slick operator in a suit: “Suddenly, no one could touch him.” Often when we talk these days about people selling their souls, they might eventually end up singing, but they don’t make beautiful music. In any case, the moral of almost every version of the story is perfectly clear: no matter how good the deal seems, the devil never fails to collect on a debt.

Related Content:

The Story of Bluesman Robert Johnson’s Famous Deal With the Devil Retold in Three Animations

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...School Principal, Forced to Resign After Students Learn About Michelangelo’s “David,” Visits the Renaissance Statue in Florence

In March, a Florida school principal lost her job when 6th graders encountered Michelangelo’s “David” during an art history lesson–even though the school ostensibly specializes in offering students “a content-rich classical education in the liberal arts and sciences.” Parents apparently found the Renaissance sculpture, um, “pornographic.”

Fast forward two months, and the former principal Hope Carrasquilla has now traveled to Florence and visited Michelangelo’s “David” in person. This came at the invitation of the mayor of Florence, Dario Nardella, and the director of the Galleria dell’Accademia, Cecilie Hollberg. Above you can see Hollberg on the left, and Carrasquilla on the right.

On Instagram, Carrasquilla commented:

I’m very impressed. The thing that strikes me the most, and that I didn’t know, is that this whole gallery was built for him [Michelangelo’s “David”]. I think it’s beautiful, it looks like a church. And to me, that just represents really the purity of this figure and you see his humanity. There is nothing wrong with the human body. Michelangelo did nothing wrong. He could only sculpt it like this. It couldn’t be otherwise. He’s wonderful and I’m really happy to be here.

In her own statement, Hollberg said:

I am delighted to welcome her and show her the magnificence of our museum, as well as personally introduce her to David, a sculpture that I reiterate has nothing to do with pornography. It is a masterpiece representing a religious symbol of purity and innocence, the triumph of good over evil. His nudity is an outward manifestation of Renaissance thought, which considered man the centre of the universe. People from all over the world, including many Americans, make the pilgrimage to admire him every year. Currently, more than 50% of visitors are from the United States. I am certain that Ms. Carrasquilla will receive the welcome and solidarity she deserves here in Florence.

Florida may be canceling classical art and thought. Florence is decidedly not.

Related Content

How Michelangelo’s David Still Draws Admiration and Controversy Today

Michelangelo’s Illustrated Grocery List

Leonardo da Vinci’s Handwritten Resume (1482)

Read More...16 Ways the World Is Getting Remarkably Better: Visuals by Statistician Hans Rosling

It certainly may not feel like things are getting better behind the anxious veils of our COVID lockdowns. But some might say that optimism and pessimism are products of the gut, hidden somewhere in the bacterial stew we call the microbiome. “All prejudices come from the intestines,” proclaimed noted sufferer of indigestion, Friedrich Nietzsche. Maybe we can change our views by changing our diet. But it’s a little harder to change our emotions with facts. We turn up our noses at them, or find them impossible to digest.

Nietzsche did not consider himself a pessimist. Despite his stomach troubles, he “adopted a philosophy that said yes to life,” notes Reason and Meaning, “fully cognizant of the fact that life is mostly miserable, evil, ugly, and absurd.” Let’s grant that this is so. A great many of us, I think, are inclined to believe it. We are ideal consumers for dystopian Nietzsche-esque fantasies about supermen and “last men.” Still, it’s worth asking: is life always and equally miserable, evil, ugly, and absurd? Is the idea of human progress no more than a modern delusion?

Physician, statistician, and onetime sword swallower Hans Rosling spent several years trying to show otherwise in television documentaries for the BBC, TED Talks, and the posthumous book Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World—and Why Things Are Better Than You Think, co-written with his son and daughter-in-law, a statistician and designer, respectively. Rosling, who passed away in 2017, also worked with his two co-authors on software used to animate statistics, and in his public talks and book, he attempted to bring data to life in ways that engage gut feelings.

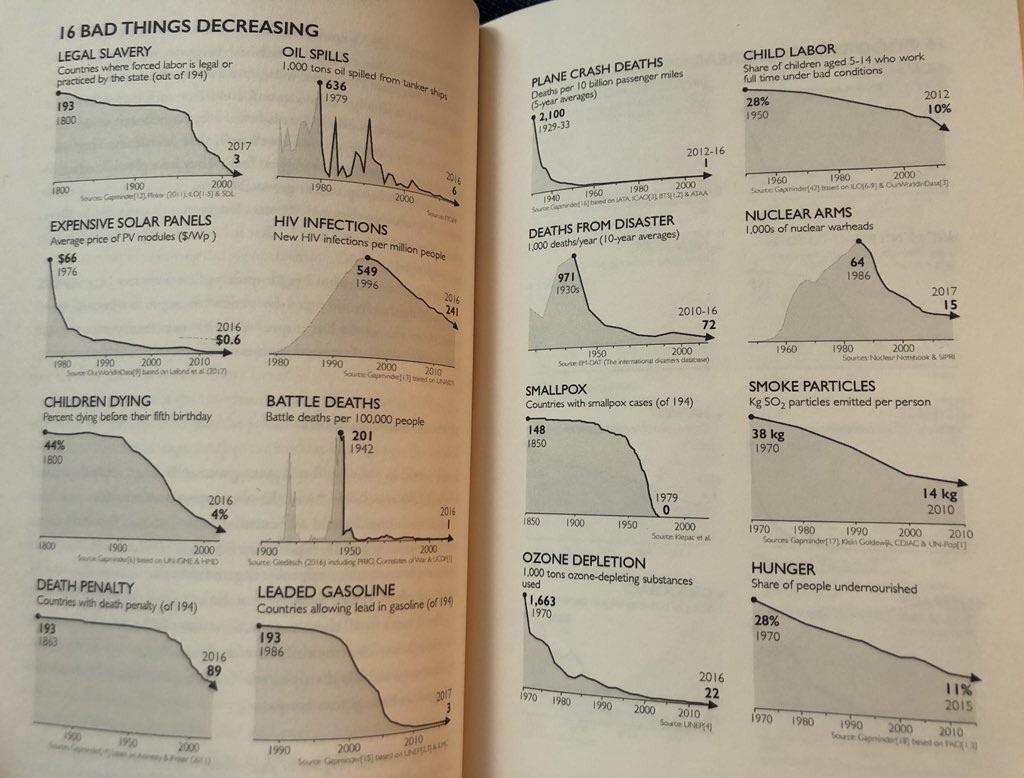

Take the set of graphs above, aka, “16 Bad Things Decreasing,” from Factfulness. (View a larger scan of the pages here.) Yes, you may look at a set of monochromatic trend lines and yawn. But if you attend to the details, you’ll can see that each arrow plummeting downward represents some profound ill, manmade or otherwise, that has killed or maimed millions. These range from legal slavery—down from 194 countries in 1800 to 3 in 2017—to smallpox: down from 148 countries with cases in 1850 to 0 in 1979. (Perhaps our current global epidemic will warrant its own triumphant graph in a revised edition some decades in the future.) Is this not progress?

What about the steadily falling rates of world hunger, child mortality, HIV infections, numbers of nuclear warheads, deaths from disaster, and ozone depletion? Hard to argue with the numbers, though as always, we should consider the source. (Nearly all these statistics come from Rosling’s own company, Gapminder.) In the video above, Dr. Rosling explains to a TED audience how he designed a course on global health in his native Sweden. In order to make sure the material measured up to his accomplished students’ abilities, he first gave them a questionnaire to test their knowledge.

Rosling found, he jokes, “that Swedish top students know statistically significantly less about the world than a chimpanzee,” who would have scored higher by chance. The problem “was not ignorance, it was preconceived ideas,” which are worse. Bad ideas are driven by many ‑isms, but also by what Rosling calls in the book an “overdramatic” worldview. Humans are nervous by nature. “Our tendency to misinterpret facts is instinctive—an evolutionary adaptation to help us make quick decisions to avoid danger,” writes Katie Law in a review of Factfulness.

“While we still need these instincts, they can also trip us up.” Magnified by global, collective anxieties, weaponized by canny mass media, the tendency to pessimism becomes reality, but it’s one that is not supported by the data. This kind of argument has become kind of a cottage industry; each presentation must be evaluated on its own merits. Presumably enlightened optimism can be just as oversimplified a view as the darkest pessimism. But Rosling insisted he wasn’t an optimist. He was just being “factful.” We probably shouldn’t get into what Nietzsche might say to that.

Related Content:

Positive Psychology: A Free Course from Harvard University

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Meet Emma Willard, the First Female Map Maker in the U.S., and Her Brilliantly Inventive Maps (Circa 1826)

Americans have never like the word “empire,” having seceded from the British Empire to ostensibly found a free nation. The founders blamed slavery on the British, naming the king as the responsible party. Three of the most distinguished Virginia slaveholders denounced the practice as a “hideous blot,” “repugnant,” and “evil.” But they made no effort to end it. Likewise, according to the Declaration of Independence, the British were responsible for exciting “domestic insurrections among us,” and endeavouring “to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages.”

These denunciations aside, the new country nonetheless began a course identical to every other European world power, waging perpetual warfare, seizing territory and vastly expanding its control over more and more land and resources in the decades after Independence.

U.S. imperial power was asserted not only by force of arms and coin but also through an ideological view that made its appearance and growth an act of both divine and secular providence. We see this view reflected especially in the making of maps and early historical infographics.

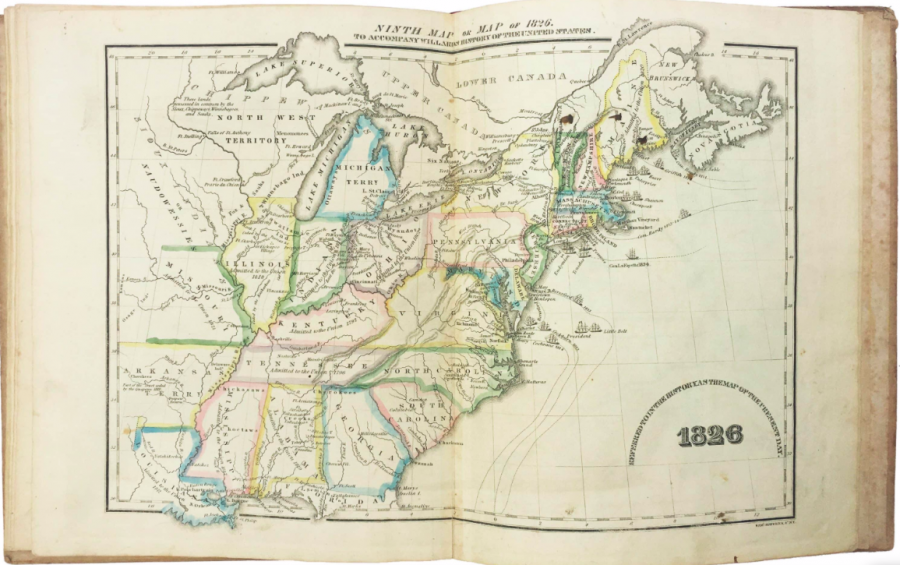

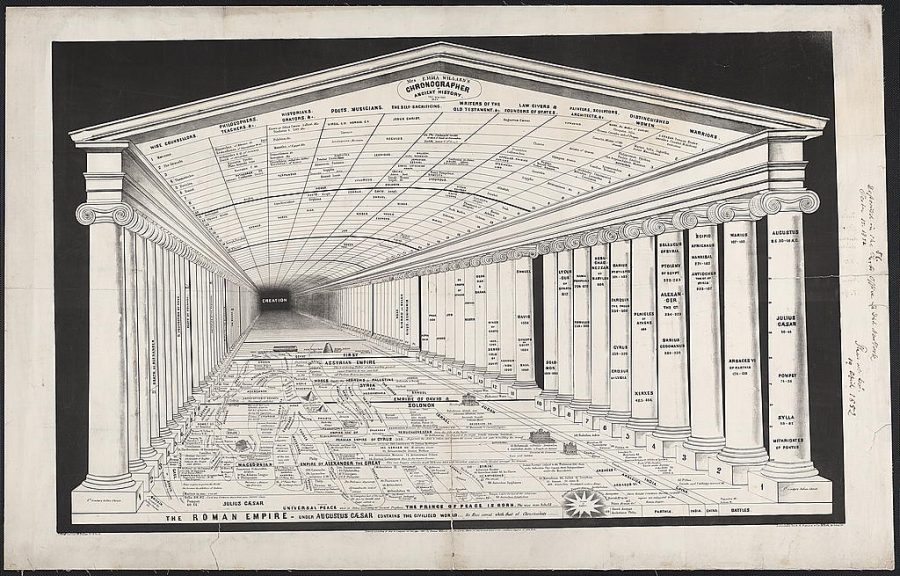

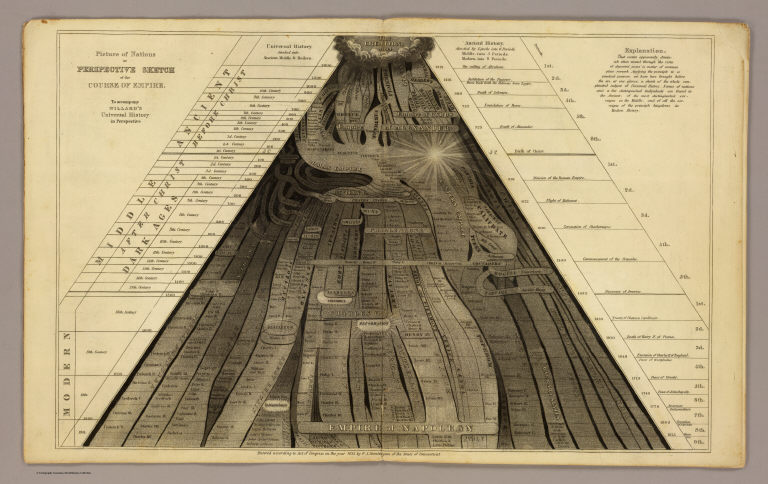

In 1851, three years after war with Mexico had halved that country and expanded U.S. territory into what would become several new states, Emma Willard, the nation’s first female mapmaker, created the “Chronographer of Ancient History” above, a visual representation to “teach students about the shape of historical time,” writes Rebecca Onion at Slate. The Chronographer is a “more specialized offshoot of Willard’s master Temple of Time, which tackled all of history”—or all six thousand years of it, anyway, since “Creation BC 4004.”

Willard made several such maps, illustrating an idea popular among 18th and 19th century historians, and illustrated in many similar ways by other artists: casting history as a succession of great empires, one taking over for another. Viewers of the map stand outside the temple’s stable framing, assured they are the inheritors of its historical largesse. Other visual metaphors told this story, too. Willard, as Ted Widmer points out at The Paris Review. Willard was an “inventive visual thinker,” if also a very conventional historical one.

In an earlier map, from 1836, Willard visualized time as a series of branching imperial streams, flowing downward from “Creation.” Curiously, she situates American Independence on the periphery, ending with the “Empire of Napoleon” at the center. The U.S. was both something new in the world and, in other maps of hers, the fruition of a seed planted centuries earlier. Willard’s mapmaking began as an effort to supplement her materials as “a pioneering educator,” founder of the Emma Willard School in Troy, New York, and a “versatile writer, publisher and yes, mapmaker,” who “used every tool available to teach young readers (and especially young women) how to see history in creative new ways.”

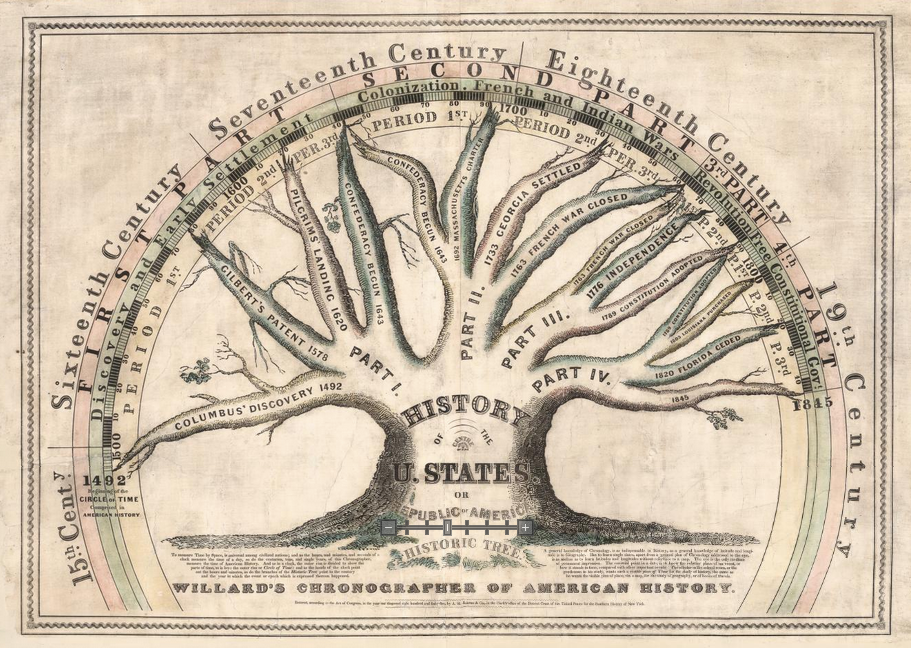

In another “chronographer” textbook illustration, she shows the “History of the U. States or Republic of America” as a tree which had been growing since 1492, though no such place as the United States existed for most of this history. Maps, writes Sarah Laskow at Atlas Obscura, “have the power to shape history” as well as to record it. Willard’s maps told grand, universal stories—imperial stories—about how the U.S. came to be. In 1828, when she was 41, “only slightly older than the United States of America itself,” Willard published a series of maps in her History of the United States, or Republic of America.

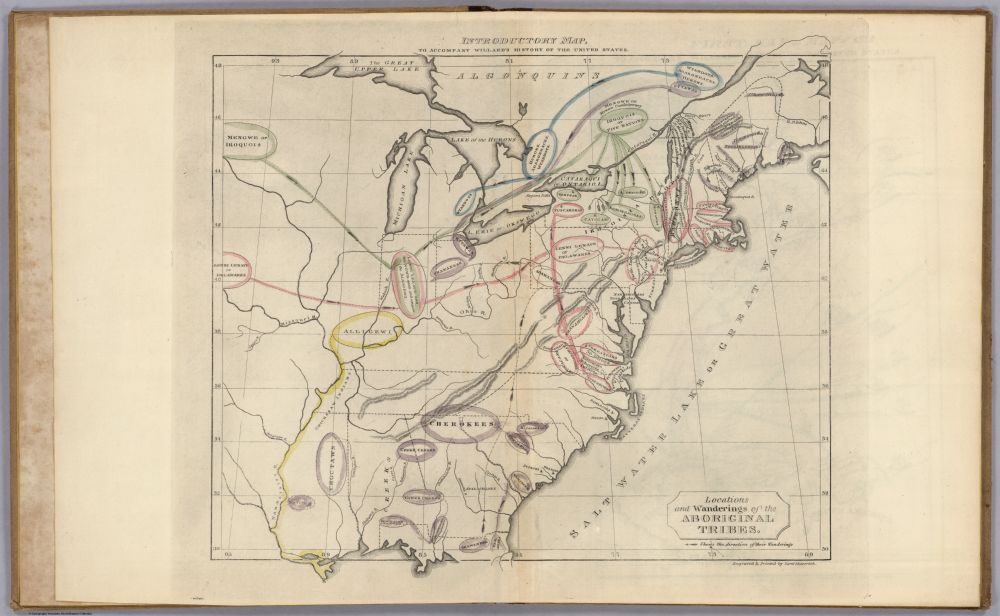

This was “the first book of its kind—the first atlas to present the evolution of America.” Willard’s maps show the movement of Indigenous nations in plates like “Locations and Wanderings of The Aboriginal Tribes… The Direction of their Wanderings,” below—these were part of “a story about the triumph of Anglo settlers in this part of the world. She helped solidify, for both her peers and her students, a narrative of American destiny and inevitability, writes University of Denver historian Susan Schulten. Willard was “an exuberant nationalist,” who generally “accepted the removal of these tribes to the west as inevitable.”

Willard was a pioneer in many respects, including, perhaps, in her adoptation of European neoclassical ideas about history and time in the justification of a new American empire. Her snapshots of time collapse “centuries into a single image,” Schulten explains, as a way of mapping time “in a different way as a prelude to what comes to next.” See many more of Willard’s maps from The History of the United States, or Republic of America, the first historical atlas of the United States, at Boston Rare Maps.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...A New Massive Helen Keller Archive Gets Launched: Take a Digital Look at Her Photos, Letters, Speeches, Political Writings & More

Take an innocuous statement like, “we should teach children about the life of Helen Keller.” What reasonable, compassionate person would disagree? Hers is a story of triumph over incredible adversity, of perseverance and friendship and love. Now, take a statement like, “we should teach children the political writing of Helen Keller,” and you might see brawls in town halls and school board meetings. This is because Helen Keller was a committed socialist and serious political thinker, who wrote extensively to advocate for economic cooperation over competition and to support the causes of working people. She was an activist for peace and justice who opposed war, imperialism, racism, and poverty, conditions that huge numbers of people seem devoted to maintaining—both in her lifetime and today.

Keller’s moving, persuasive writing is eloquent and uncompromising and should be taught alongside that of other great American rhetoricians. Consider, for example, the passage below from a letter she wrote in 1916 to Oswald Villard, then Vice-President of the NAACP:

Ashamed in my very soul I behold in my own beloved south-land the tears of those who are oppressed, those who must bring up their sons and daughters in bondage to be servants, because others have their fields and vineyards, and on the side of the oppressor is power. I feel with those suffering, toiling millions, I am thwarted with them. Every attempt to keep them down and crush their spirit is a betrayal of my faith that good is stronger than evil, and light stronger than darkness…. My spirit groans with all the deaf and blind of the world, I feel their chains chafing my limbs. I am disenfranchised with every wage-slave. I am overthrown, hurt, oppressed, beaten to the earth by the strong, ruthless ones who have taken away their inheritance. The wrongs of the poor endure ring fiercely in my soul, and I shall never rest until they are lifted into the light, and given their fair share in the blessings of life that God meant for us all alike.

It is difficult to choose any one passage from the letter because the whole is written with such expressive feeling. This is but one document among many hundreds in the new Helen Keller archive at the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB), which has digitized letters, essays, speeches, photographs, and much more from Keller’s long, tireless career as a writer and public speaker. Funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the archive includes over 250,000 digital images of her work from the late 19th century to well into the 20th. There are many films of Keller, photos like that of her and her dog Sieglinde at the top, a collection of her correspondence with Mark Twain, and much more.

In addition to Keller’s own published and unpublished work, the archive contains many letters to and about her, press clippings, informative AFB blog posts, and resources for students and teachers. The site aims to be “fully accessible to audiences who are blind, deaf, hard-of-hearing, low vision, or deafblind.” On the whole, this project “presents an opportunity to encounter this renowned historical figure in a new, dynamic, and exciting way,” as AFB writes in a press release. “For example, despite her fame, relatively few people know that Helen Keller wrote 14 books as well as hundreds of essays and articles on a broad array of subjects ranging from animals and atomic energy to Mahatma Gandhi.”

And, of course, she was a lifelong advocate for the blind and deaf, writing and speaking out on disability rights issues for decades. Indeed, it’s difficult to find a subject in which she did not take an interest. The archive’s subject index shows her writing about games, sports, reading, shopping, swimming, travel, architecture and the arts, education, law, government, world religions, royalty, women’s suffrage, and more. There were many in her time who dismissed Keller’s unpopular views, calling her naïve and claiming that she had been duped by nefarious actors. The charge is insulting and false. Her body of work shows her to have been an extraordinarily well-read, wise, cosmopolitan, sensitive, self-aware, and honest critical thinker.

Two years after the NAACP letter, Keller wrote an essay called “Competition,” in which she made the case for “a better social order” against a central conceit of capitalism: that “life would not be worth while without the keen edge of competition,” and that without it “men would lose ambition, and the race would sink into dull sameness.” Keller advances her counterargument with vigorous and incisive reasoning.

This whole argument is a fallacy. Whatever is worth while in our civilization has survived in spite of competition. Under the competitive system the work of the world is badly done. The result is waste and ruin [….] Profit is the aim, and the public good is a secondary consideration. Competition sins against its own pet god efficiency. In spite of all the struggle, toil and fierce effort the result is a depressing state of destitution for the majority of mankind. Competition diverts man’s energies into useless channels and degrades his character. It is immoral as well as inefficient, since its commandment is “Thou shalt compete against thy neighbor.” Such a rule does not foster Truthfulness, honesty, consideration for others. [….] Competitors are indifferent to each other’s welfare. Indeed, they are glad of each other’s failure because they find their advantage in it. Compassion is deadened in them by the necessity they are under of nullifying the efforts of their fellow-competitors.

Keller refused to become cynical in the face of seemingly indefatigable greed, cruelty, and hypocrisy. Though not a member of a mainstream church (she belonged to the obscure Christian sect of Swedenborgianism), she exhorted American Christians to live up to their professions—to follow the example of their founder and the commandments of their sacred text. In an essay written after World War I, she argued movingly for disarmament and “the vital issue of world peace.” While making a number of logical arguments, Keller principally appeals to the common ethos of the nation’s dominant faith.

This is precisely where we have failed, calling ourselves Christians we have fundamentally broken, and taught others to break most patriotically, the commandment of the Lord, “Thou shalt not kill” [….] Let us then try out Christianity upon earth—not lip-service, but the teaching of Him who came upon earth that “all men might have life, and have it more abundantly.” War strikes at the very heart of this teaching.

We can hear Helen Keller’s voice speaking directly to us from the past, diagnosing the ills of her age that look so much like those of our own. “The mythological Helen Keller,” writes Keith Rosenthal, “has aptly been described as a sort of ‘plaster saint;’ a hollow, empty vessel who is little more than an apolitical symbol for perseverance and personal triumph.” Though she embodied those qualities, she also dedicated her entire life to careful observation of the world around her, to writing and speaking out on issues that mattered, and to caring deeply about the welfare of others. Get to know the real Helen Keller, in all her complexity, fierce intelligence, and ferocious compassion, at the American Foundation for the Blind’s exhaustive digital archive of her life and work.

Related Content:

Watch Helen Keller & Teacher Annie Sullivan Demonstrate How Helen Learned to Speak (1930)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Enter an Archive of Over 95,000 Aerial Photographs Taken Over Britain from 1919 to 2006

As deep as we get into the 21st century, many of us still can’t stop talking about the 20th. That goes especially for those of us from the West, and specifically those of us from America and Britain, places that experienced not just an eventful 20th century but a triumphant one: hence, in the case of the former, the designation “the American Century.” And even though that period came after the end of Britain’s supposed glory days, the “Imperial Century” of 1815–1914, the United Kingdom changed so much from the First World War to the end of the millennium — not just in terms of what lands it comprised, but what was appearing and happening on them — that words can’t quite suffice to tell the story.

Enter Britain from Above, an archive of over 95,000 pieces of aerial photography of Britain taken not just from the air but from the sweep of history between 1919 and 2006. Its pictures, says its about page, come from “the Aerofilms collection, a unique aerial photographic archive of international importance.

The collection includes 1.26 million negatives and more than 2000 photograph albums.” Originally created by Aerofilms Ltd, an air survey set up by a couple veterans of World War I and later expanded to include smaller collections from the archives of two other companies, it “presents an unparalleled picture of the changing face of Britain in the 20th century” and “includes the largest and most significant number of air photographs of Britain taken before 1939.”

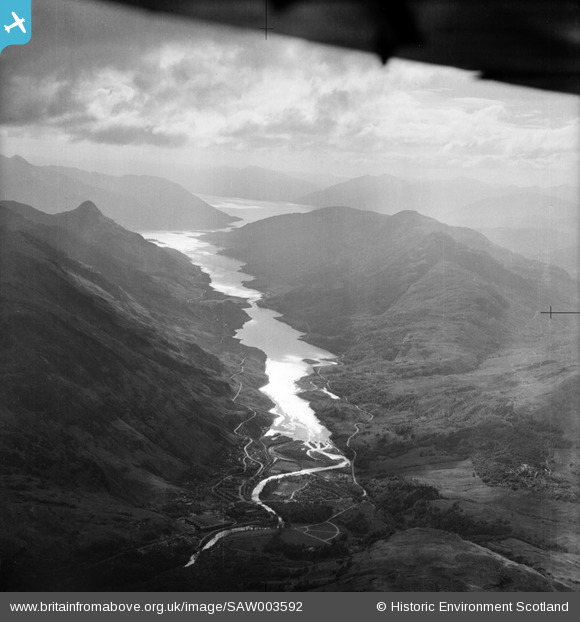

Here you see just four selections from among those 95,000 images from the Aerofilms collection digitized by the four-year-long Britain from Above project with the goal of conserving its “oldest and most valuable” photographs. At the top of the post, see bomb damaged and cleared areas to the east of St Paul’s Cathedral, London, 1947. Then wingwalker Martin Hearn does his daredevilish job in 1932. Below that, a nearly abstract pattern of housing stretches out around St. Aidan’s Church in Leeds in 1929, the light ship Alarm passes the SS Collegian in Liverpool Bay in 1947; and Scotland’s Loch Leven passes through the Mam na Gualainn in that same year.

Attaining a firm grasp of a place’s history often requires what we metaphorically call a “view from 30,000 feet,” but in the case of one of the leading parts of the world in as technologically and developmentally heady a time as the 20th century, we mean it literally. Enter the Britain from Above photo archive here.

Related Content:

1927 London Shown in Moving Color

A Dazzling Aerial Photograph of Edinburgh (1920)

Amazing Aerial Photographs of Great American Cities Circa 1906

Free: British Pathé Puts Over 85,000 Historical Films on YouTube

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...When Ira Aldridge Became the First Black Actor to Perform Shakespeare in England (1824)

The ways that Othello, Aaron the Moor from Titus Andronicus, and Shylock from The Merchant of Venice—Shakespeare’s “explicitly racialized characters,” as George Washington University’s Ayanna Thompson puts it—have been interpreted over the centuries may have less to do with the author’s intentions and more with contemporary ideas about race, the actors cast in the roles, and the directorial choices made in a production. To a great degree, these characters have been played as though their identities were like the costumes put on by actors who darkened their faces or wore stereotypical markers of ethnic or religious Judaism (including “an obnoxiously large nose”).

Such portrayals risk turning complex characters into caricatures, validating much of what we might see as overt and implicit racism in the text. But there are those, Thompson says, who think such roles are actually “about racial impersonation.” Othello, for example, is “a role written by a white man, intended for a white actor in black makeup.”

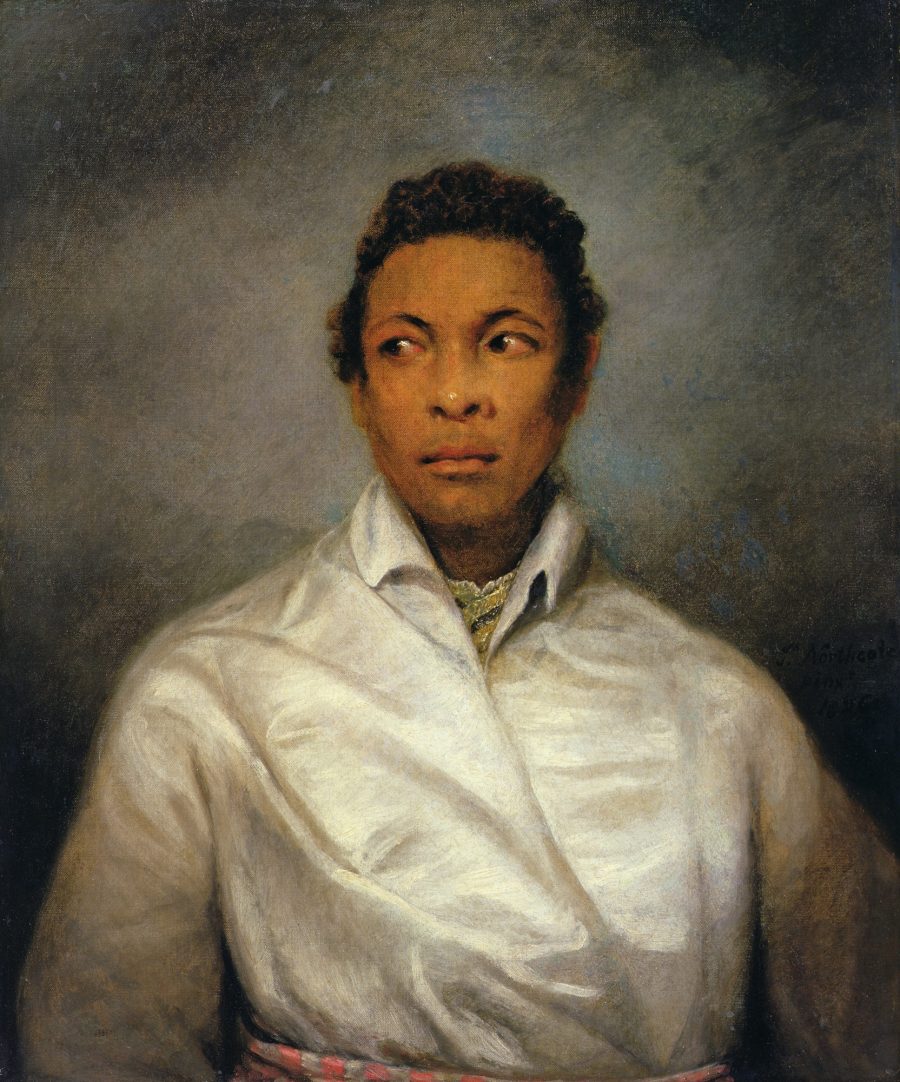

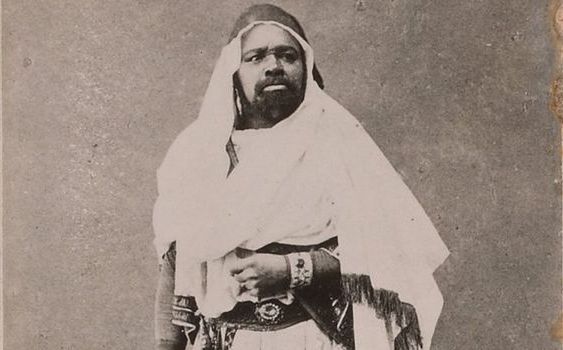

For centuries, that is what most audiences fully expected to see. The tradition continued in Britain until the 19th century, when the Shakespearean color line, so to speak, was first crossed by Ira Aldridge, an American actor born in New York City in 1807.

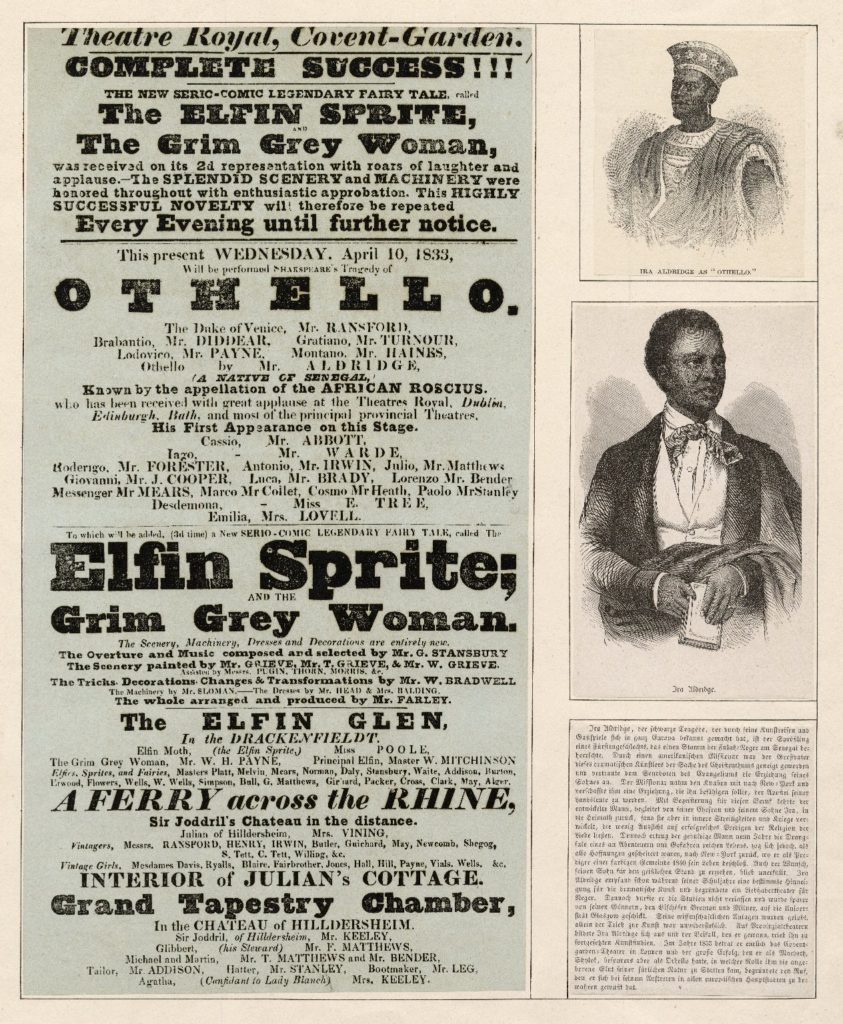

“Educated at the African Free School,” notes the Folger Shakespeare Library, Aldridge “was able to see Shakespeare plays at the Park Theatre and the African Grove Theatre.” He took on roles like Romeo with the African Company, but “New York was generally not a welcoming place for black actors… some white theatergoers even attempted to prevent black companies from performing Shakespeare at all.” As Tony Howard, an English professor at the University of Warwick, tells PRI, “he was beaten up in the streets.” And so Aldridge left for England in 1824, where he played Othello at the Theatre Royal, Covent-Garden, at only 17 years old, the first black actor to play a Shakespearean role in Britain.

He later began performing under the name Keene, “a homonym,” notes the site Black History 365, “for the then popular British actor, Edmund Kean.” Aldridge’s big break came after he met Kean and his son Charles, also an actor, in 1831, and both became supporters of his career. When the elder Kean collapsed onstage in 1833, then died, Aldridge took over his role as Othello at London’s Royalty Theatre in two performances. “Critics objected,” the Folger writes, “to his race, his youth, and his inexperience.” As Howard tells it, this characterization is a gross understatement:

There were those who said this is a very interesting and extraordinary young actor. And the fact that he’s a black actor makes it more interesting and fascinating. But for many people, it was an insult because this is still a society where there is a great deal of slavery in the British Empire. And in order to combat the idea of increasing abolition, performers like Ira had to be stopped. And so there was a great deal of violent aggression. Not physical violence this time, but violence in the press.

Some of that verbal violence included comparing Aldridge to “performing horses” and “performing dogs.” Many London critics saw his entry on the Shakespearean stage as an affront to English literary tradition. Performing the bard’s works was “a kind of violation,” Howard summarizes, “he has no right to do that, not even to play Othello.”

Photo via the Folger Library

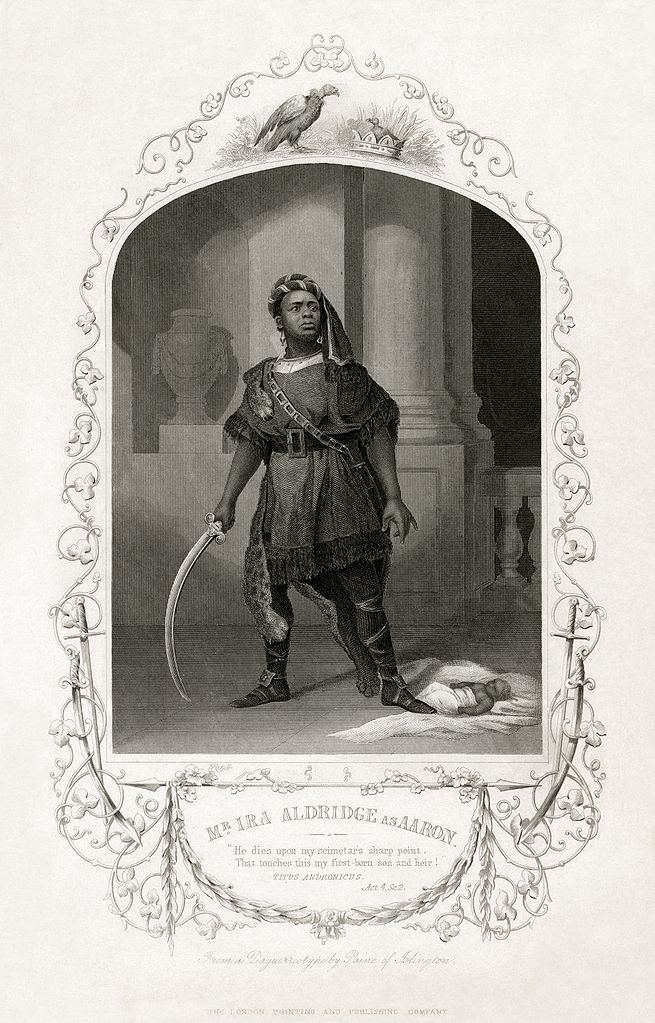

From his beginnings in Coventry to his experience in London, Aldridge made the once-blackface role his own, perhaps increasingly drawing “on his own experience and his own feeling.” He also portrayed Aaron in Titus, and as he persevered through negative press and prejudice, he took on other starring roles, including Richard III, Shylock, Iago, King Lear, and Macbeth. He “toured the English provinces extensively,” the BBC writes, “and stayed in Coventry for a few months, during which time he gave a number of speeches on the evils of slavery. When he left, people inspired by his speeches went to the county hall and petitioned for its abolition.”

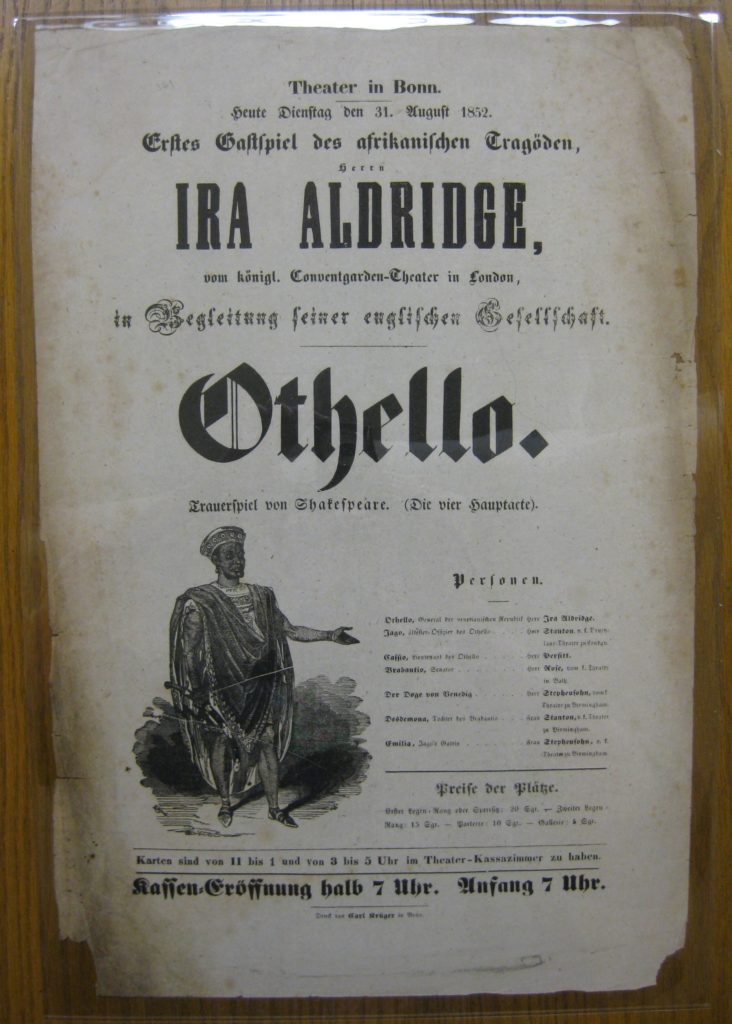

By the end of the 1840s, however, Aldridge felt he had gone as far as he could go in England and left to tour the Continent in what had become his signature role, Othello. While first touring with an English company, he “later began to work with local theater troupes,” the Folger writes, “performing in English while the rest of the cast would perform in German, Swedish, etc. Despite the language barrier, Aldridge’s performances in Europe were highly acclaimed, a testament to his acting skills.” (See a playbill further up from a Bonn performance.) After winning great fame in Europe and Russia, the actor returned in triumph to London in 1855, and this time was very well-received.

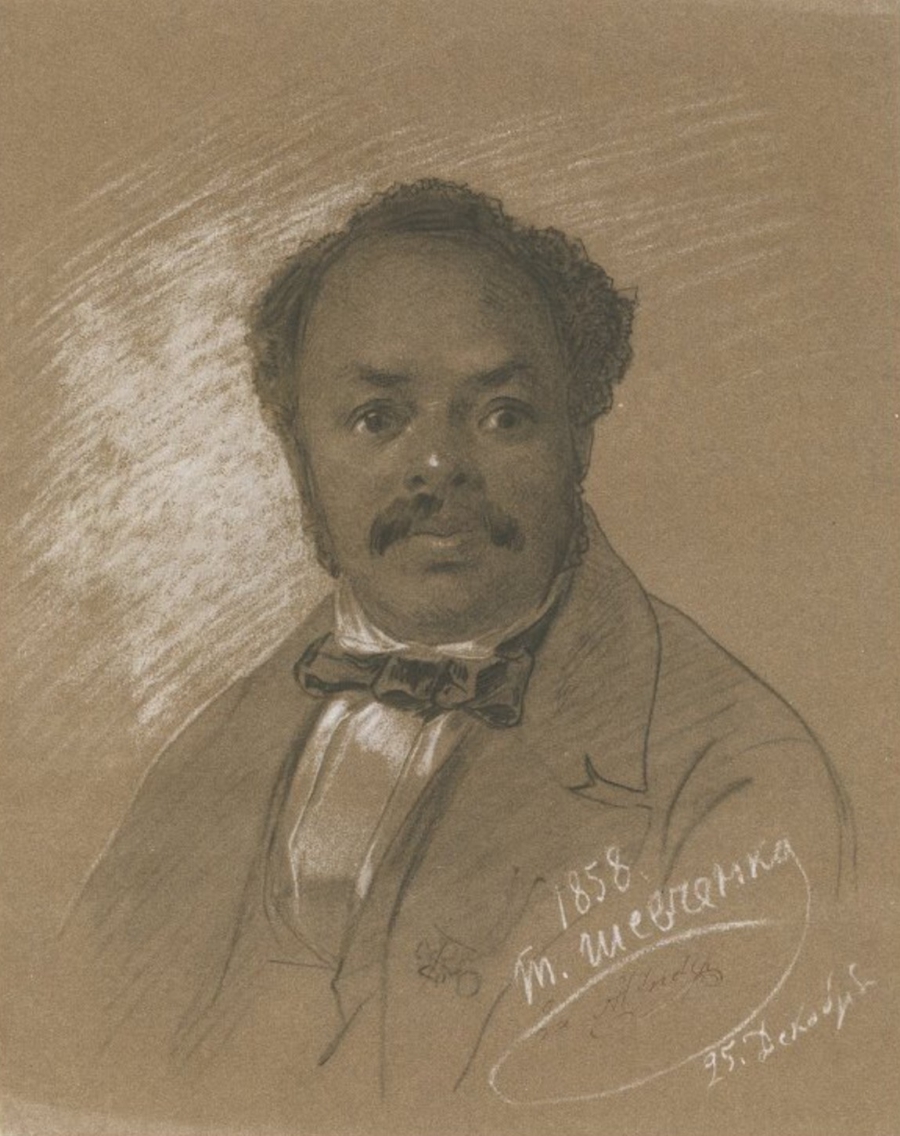

Aldridge died in 1867. And though he was the subject of many portraits of the period—like that by James Northcote at the top of the post, portraying the 19-year-old Aldridge as Othello, and this 1830 painting by Henry Perronet Briggs—he was “largely forgotten by theater historians.” (See him above in an 1858 drawing by Ukranian artist Taras Shevchenko.) But his legacy has been revived in recent years. Aldridge was the subject of two recent plays, Black Othello, by Cecilia Sidenbladh, and Red Velvet by Lolita Chakrabarti. And last year, he was honored in Coventry by a plaque on the site of the theater where he first achieved fame.

While he succeeded in becoming an all-around great Shakespearean actor, Aldridge’s legacy rests especially in the way he helped transform roles performed as “racial impersonation” for a few hundred years into the provenance of talented black actors who bring new depth, complexity, and authenticity to characters often played as stock ethnic villains. While white actors like Orson Welles and Lawrence Olivier continued to play Othello well into the 20th century, these days such casting can be seen as “ridiculous,” as Hugh Muir writes at The Guardian, especially if that actor “blacks up” for the role.

via the British Library

Related Content:

What Shakespeare’s English Sounded Like, and How We Know It

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Bob Dylan Plays Tom Petty’s “Learning to Fly” Live in Concert (and How Petty Witnessed Dylan’s Musical Epiphany in 1987)

While performing in Denver this past weekend, Bob Dylan paid tribute to Tom Petty, playing a cover of his 1991 track, “Learning to Fly.” Most will remember their time together in the Traveling Wilburys. But really their relationship was cemented before that, when the musicians embarked on the long True Confessions Tour in 1986. That’s when Dylan lost his mojo and nearly ended his career, then suddenly found new inspiration again, all while Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers shared the same stage.

In his 2004 memoir, Chronicles: Volume 1, Dylan laid out the scenario:

I’d been on an eighteen month tour with Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers. It would be my last. I had no connection to any kind of inspiration. Whatever had been there to begin with had all vanished and shrunk. Tom was at the top of his game and I was at the bottom of mine. I couldn’t overcome the odds. Everything was smashed. My own songs had become strangers to me. It wasn’t my moment of history anymore. There was a hollowing singing in my heart and I couldn’t wait to retire and fold the tent. One more big payday with Petty and that would be it for me. I was what they called over the hill.… The mirror had swung around and I could see the future — an old actor fumbling in garbage cans outside the theatre of past triumphs.

Everything finally came to a head one night when Dylan performed with Petty and the Heartbreakers in Locarno, Switzerland. He writes again in Chronicles, “For an instant, I fell into a black hole… I opened my mouth to sing and the air tightened up–vocal presence was extinguished and nothing came out.” Panicked, Dylan used every trick to get started. Nothing worked, until, he then cast his own “spell to drive out the devil.” That’s when “Everything came back, and it came back in multidimension.” A complete “metamorphosis had taken place.” He adds: “The shows with Petty finished up in December, and I saw that instead of being stranded somewhere at the end of the story, I was actually in the prelude to the beginning of another one.” Without out it, we wouldn’t have Oh Mercy, Time Out of Mind, Love and Theft, or Modern Times.

You can watch footage of the epiphany concert on Youtube. It took place on October 2, 1987–thirty years and three days before Petty’s death on October 5, 2017.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Bob Dylan & The Grateful Dead Rehearse Together in Summer 1987: Hear 74 Tracks

Read More...