Hunter S. Thompson has been gone for two decades now. When he went out, as the new Pursuit of Wonder video on his life and work reminds us, he did so in a highly American manner: with a gun, and at the moment of his own choosing. Even his longtime fans who respected something about the agency evident in that choice naturally regretted that he’d made it; many of us have wished aloud that we could read his judgments of the past twenty years’ developments in U.S. politics, culture, and society, which would certainly fit in well enough with the narrative of decline he’d pursued since the late sixties.

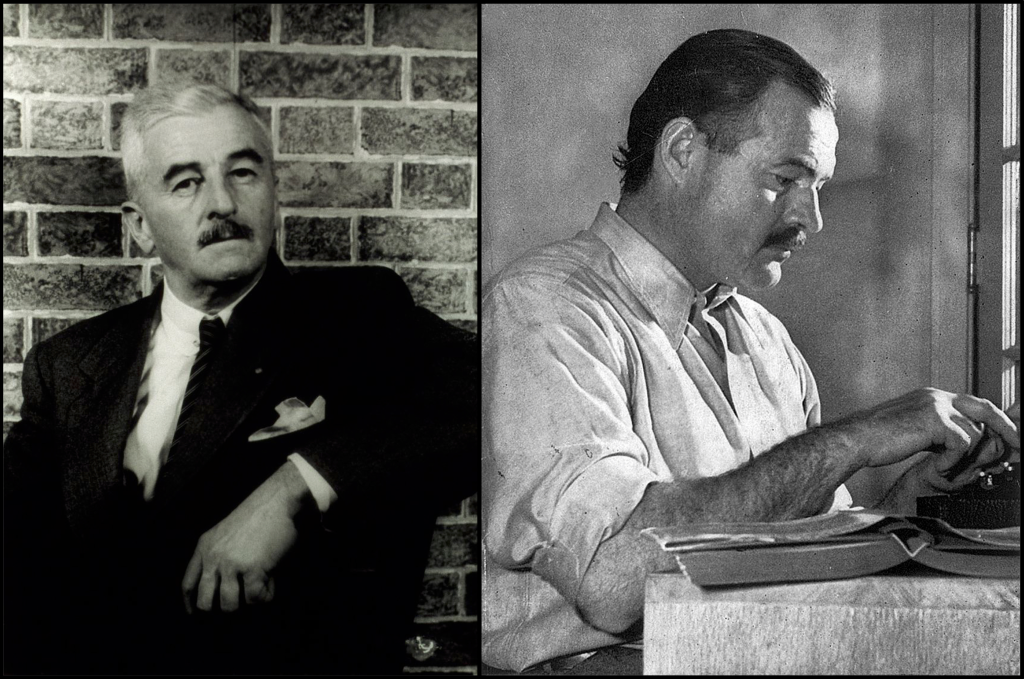

At the same time, we recognize that Thompson’s manner of living would hardly have allowed him to live into his late eighties (the man himself expressed surprise to have reached his sixties), and that it was inextricable from his manner of writing. Which is not to call it the main ingredient: as generations of imitators have proven, ingestion of controlled substances and a disrespect for traditional narrative structure do not, by themselves, constitute a recipe for the “gonzo journalism” Thompson pioneered. In fact, he had a healthy respect for structure, cultivated through his early career in workaday reportage and a self-imposed training regime that involved re-typing the whole of A Farewell to Arms and The Great Gatsby.

Gonzo journalism, according to the narrator of the video, actually has a serious question to ask: “Are not the particular subjective filters by which facts and events are processed and imagined in a moment in history as relevant as the facts themselves in understanding the truth of that moment, or at least a slice of the truth?” Thompson’s most widely read books Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72 stand as two attempts at an answer. But from the late seventies onward, as his “lifelong companions of drugs and chaotic behavior nestled closer, the lines between his larger-than-life character in his work, his public persona, and his true self began to blur.”

It could be said that Thompson never recovered the deceptive clarity of his Fear and Loathing-era work, though he remained prolific to the end. Indeed, there’s much of value in his last three decades of writing for readers attuned to who he really was. “He was not merely the character he portrayed in his work and public life, but the man who cared enough, and was talented enough, to create this character in order to explore, understand, and represent a very nuanced condition of the world during his time.” It would, perhaps, have been better if he’d been able, at some point, to retire the drugs, the firearms, the sunglasses, and the paranoia and come up with a new persona. What kept him from doing so? Maybe the notion, as articulated by his great inspiration Fitzgerald, that there are no second acts in American lives.

Related content:

Read 9 Free Articles by Hunter S. Thompson That Span His Gonzo Journalist Career (1965–2005)

Hunter S. Thompson, Existentialist Life Coach, Gives Tips for Finding Meaning in Life

Read 18 Lost Stories From Hunter S. Thompson’s Forgotten Stint As a Foreign Correspondent

Hunter S. Thompson’s Harrowing, Chemical-Filled Daily Routine

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.