Smithsonian Digitizes & Lets You Download 40,000 Works of Asian and American Art

Art lovers who visit my hometown of Washington, DC have an almost embarrassing wealth of opportunities to view art collections classical, Baroque, Renaissance, modern, postmodern, and otherwise through the Smithsonian’s network of museums. From the East and West Wings of the National Gallery, to the Hirshhorn, with its wondrous sculpture garden, to the American Art Museum and Renwick Gallery—I’ll admit, it can be a little overwhelming, and far too much to take in during a weekend jaunt, especially if you’ve got restless family in tow. (One can’t, after all, miss the Natural History or Air and Space Museums… or, you know… those monuments.)

In all the bustle of a DC vacation, however, one collection tends to get overlooked, and it is one of my personal favorites—the Freer and Sackler Galleries, which house the Smithsonian’s unique collection of Asian art, including the James McNeill Whistler-decorated Peacock Room. (See his “Harmony in Blue and Gold” above.)

Standing in this re-creation of museum founder Charles Freer’s personal 19th century gallery—which he had relocated from London to his Detroit mansion in 1904—is an aesthetic experience like no other. And like most such experiences, there really is no virtual equivalent. Nonetheless, should you have to hustle past the Freer and Sackler collections on your DC vacation, or should you be unable to visit the nation’s capital at all, you can still get a taste of the beautiful works of art these buildings contain.

Like many major museums all over the world—including the National Gallery, the Rijksmuseum, The British Library, and over 200 others—the Freer/Sackler has made its collection, all of it, available to view online. You can also download much of it.

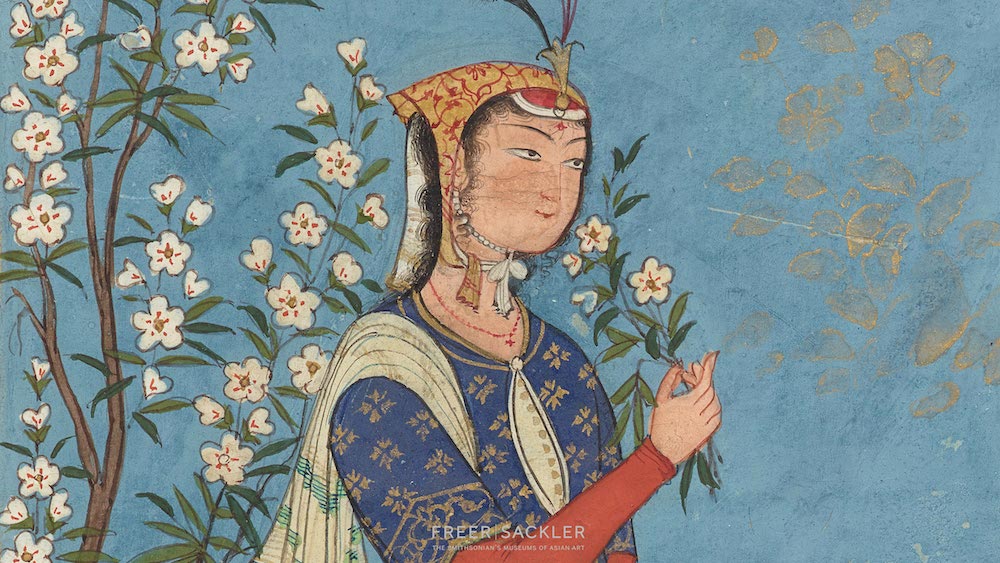

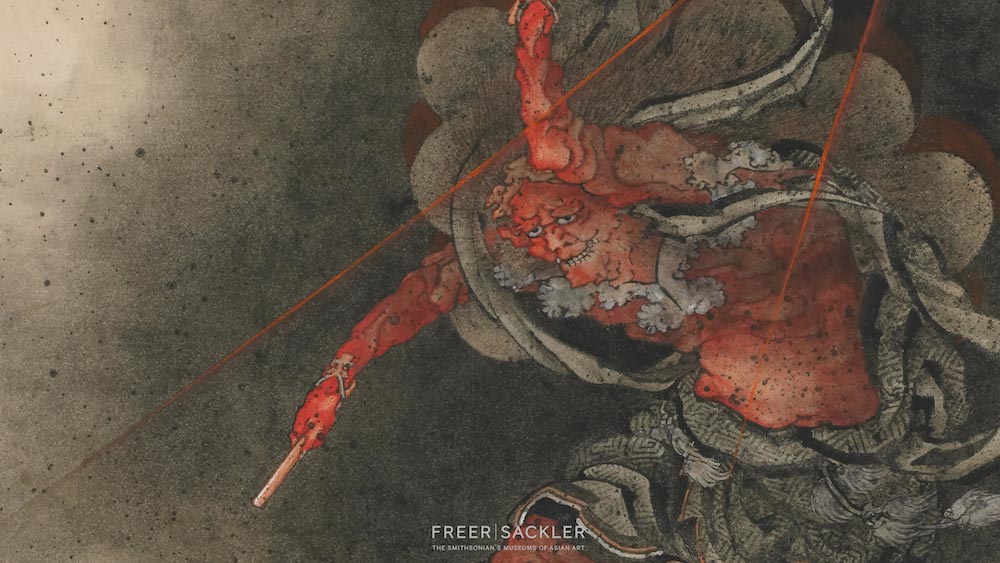

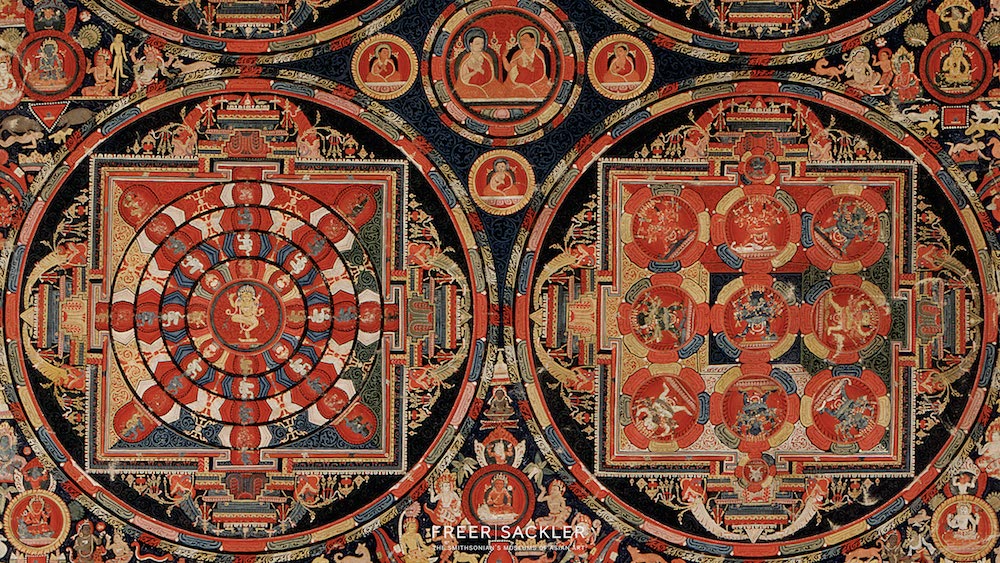

See delicate 16th century Iranian watercolors like “Woman with a spray of flowers” (top), powerful Edo period Japanese ink on paper drawings like “Thunder god” (above), and astonishingly intricate 15th century Tibetan designs like the “Four Mandala Vajravali Thangka” (below). And so, so much more.

As Freer/Sackler director Julian Raby describes the initiative, “We strive to promote the love and study of Asian art, and the best way we can do so is to free our unmatched resources for inspiration, appreciation, academic study, and artistic creation.” There are, writes the galleries’ website, Bento, “thousands of works now ready for you to download, modify, and share for noncommercial purposes.” More than 40,000, to be fairly precise.

You can browse the collection to your heart’s content by “object type,” topic, name, place, date, or “on view.” Or you can conduct targeted searches for specific items. In addition to centuries of art from all over the far and near East, the collection includes a good deal of 19th century American art, like the sketch of Whistler’s mother, below, perhaps a preparatory drawing for his most famous painting. Though I do recommend that you visit these exquisite galleries in person if you can, you must at least take in their collections via this generous online collection and its bounty of international artistic treasures. Get started today.

Related Content:

40,000 Artworks from 250 Museums, Now Viewable for Free at the Redesigned Google Art Project

Rijksmuseum Digitizes & Makes Free Online 210,000 Works of Art, Masterpieces Included!

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Grandma Moses Started Painting Seriously at Age 77, and Soon Became a Famous American Artist

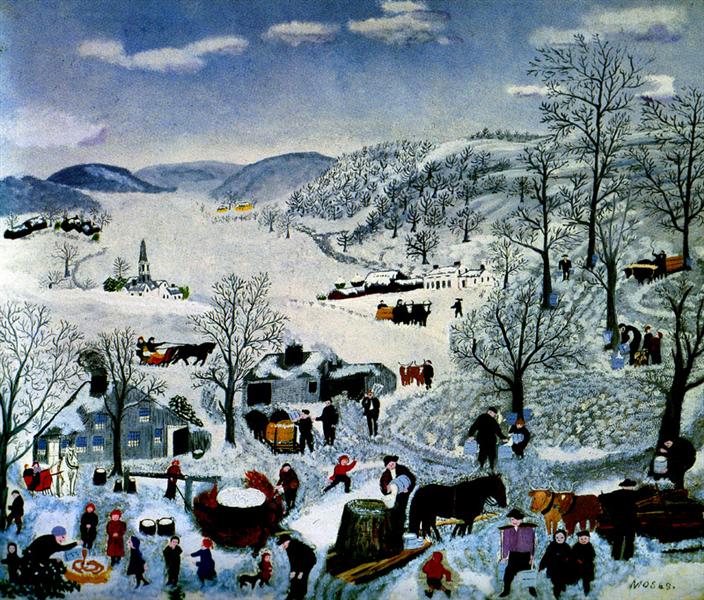

As an artistic child growing up on a farm in the 1860s and early 1870s, Anna Mary Robertson (1860–1961) used ground ochre, grass, and berry juice in place of traditional art supplies. She was so little, she referred to her efforts as “lambscapes.” Her father, for whom painting was also a hobby, kept her and her brothers supplied with paper:

He liked to see us draw pictures, it was a penny a sheet and lasted longer than candy.

She left home and school at 12, serving as a full-time, live-in housekeeper for the next 15 years. She so admired the Currier & Ives prints hanging in one of the homes where she worked that her employers set her up with wax crayons and chalk, but her duties left little time for leisure activities.

Free time was in even shorter supply after she married and gave birth to ten children — five of whom survived past infancy. Her creative impulse was confined to decorating household items, quilting, and embroidering gifts for family and friends.

At the age of 77 (circa 1937), widowed, retired, and suffering from arthritis that kept her from her accustomed household tasks, she again turned to painting.

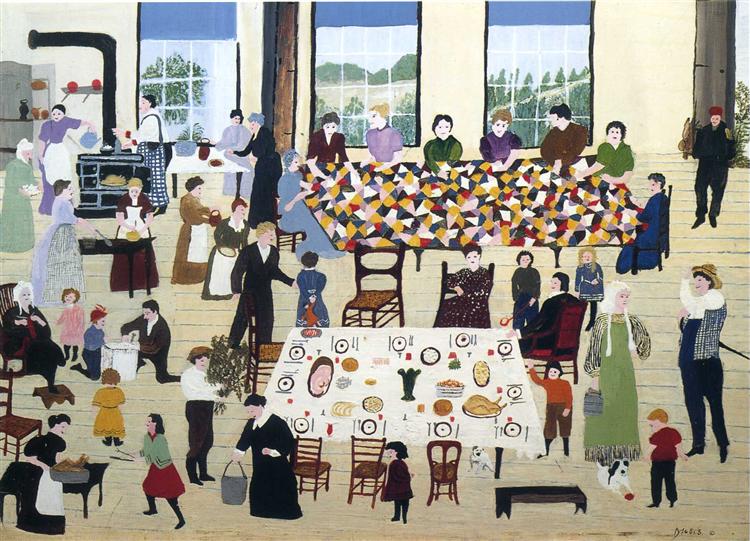

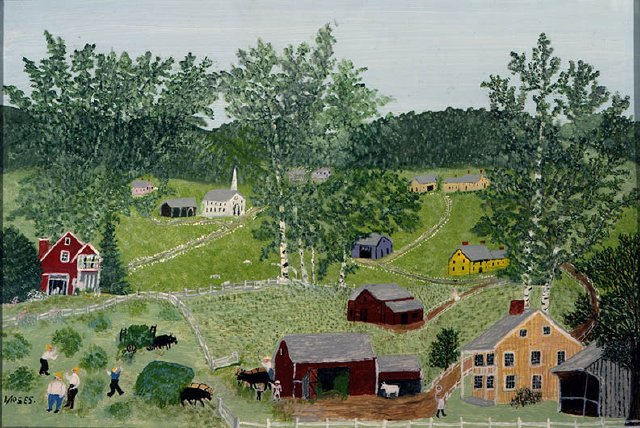

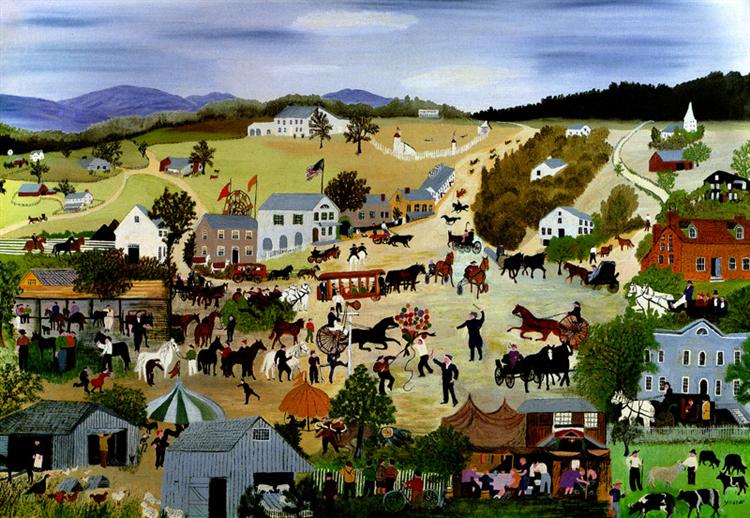

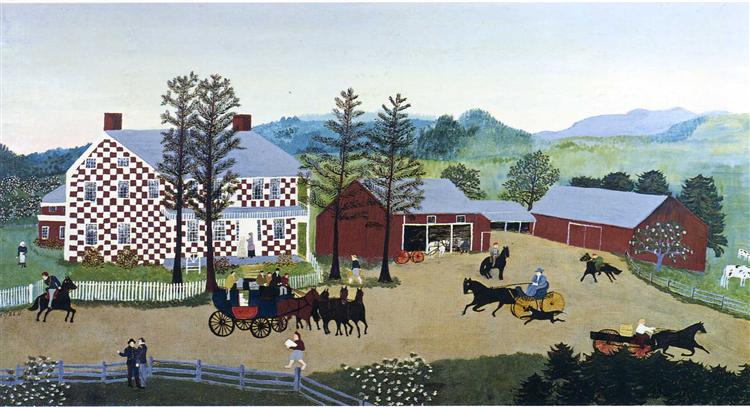

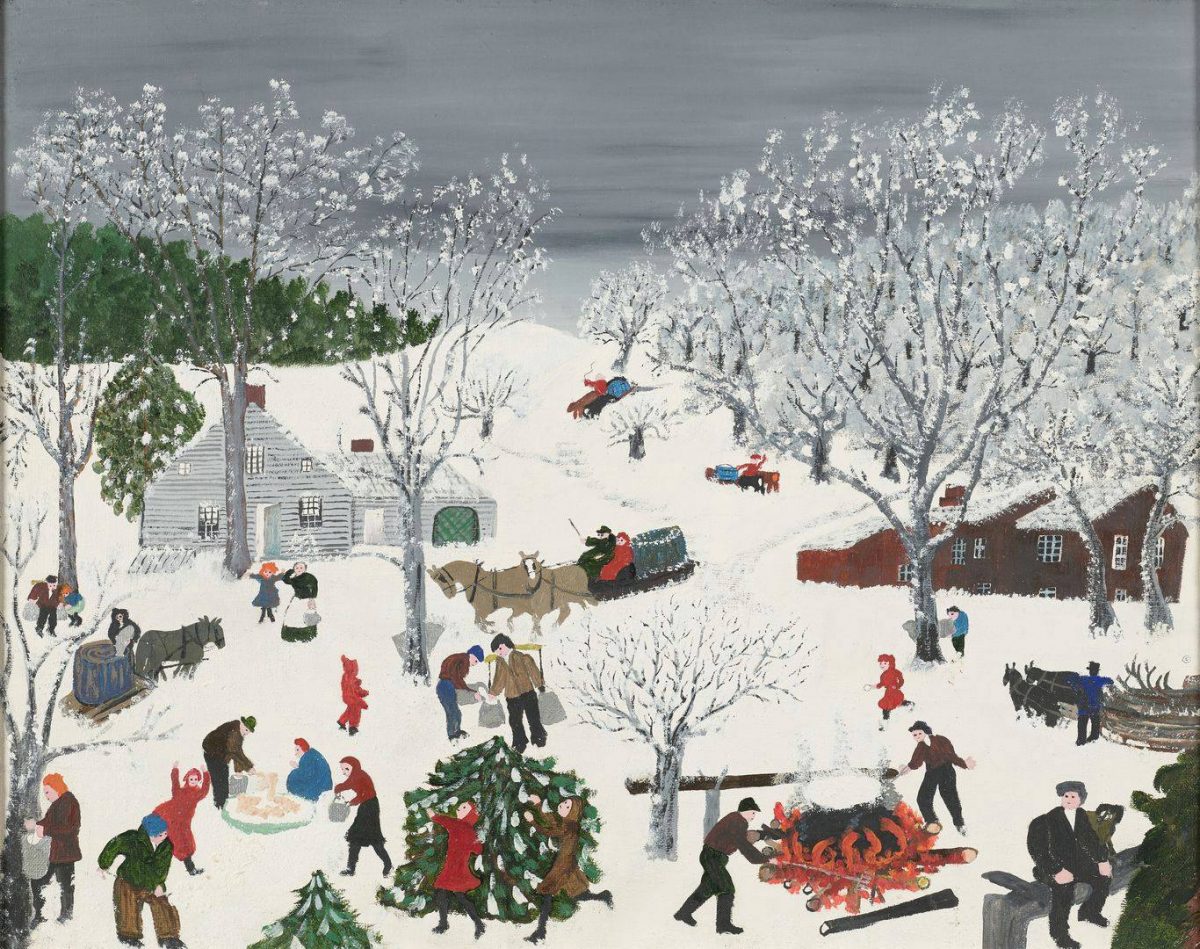

Setting up in her bedroom, she worked in oils on masonite prepped with three coats of white paint, drawing on such youthful memories as quilting bees, haying, and the annual maple sugar harvest for subject matter, again and again.

Thomas’ Pharmacy in Hoosick Falls, New York exhibited some of her output, alongside other local women’s handicrafts. It failed to attract much attention, until art collector Louis J. Caldor wandered in during a brief sojourn from Manhattan and acquired them all for an average price tag of $4.

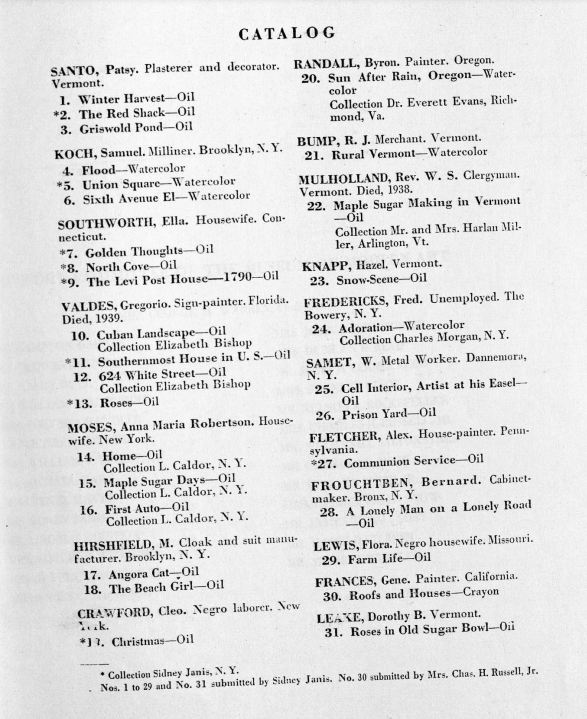

The next year (1939), Mrs. Moses, as she was then known, was one of several “housewives” whose work was included in the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibit “Contemporary Unknown American Painters”. The emphasis was definitely on the untaught outsider. In addition to occupation, the catalogue listed the non-Caucasian artists’ race…

In short order, Anna Mary Robertson Moses had a solo exhibition in the same gallery that would give Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele their first American one-person shows, Otto Kallir’s Galerie St. Etienne.

In reviewing the 1940 show, the New York Herald Tribune’s critic cited the folksy nickname (“Grandma Moses”) favored by some of the artist’s neighbors. Her wholesome rural bonafides created an unexpected sensation. The public flocked to see a table set with her homemade cakes, rolls, bread and prize-winning preserves as part of a Thanksgiving-themed meet-and-greet with the artist at Gimbels Department Store the following month.

As critic and independent curator Judith Stein observes in her essay “The White Haired Girl: A Feminist Reading”:

In general, the New York press distanced the artist from her creative identity. They commandeered her from the art world, fashioning a rich public image that brimmed with human interest…Although the artist’s family and friends addressed her as “Mother Moses” and “Grandma Moses” interchangeably, the press preferred the more familiar and endearing form of address. And “Grandma” she became, in nearly all subsequent published references. Only a few publications by-passed the new locution: a New York Times Magazine feature of April 6, 1941; a Harper’s Bazaar article; and the landmark They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the 20th Century, by the respected dealer and curator Sidney Janis, referred to the artist as “Mother Moses,” a title that conveyed more dignity than the colloquial diminutive “Grandma.”

But “Grandma Moses” had taken hold. The avalanche of press coverage that followed had little to do with the probity of art commentary. Journalists found that the artist’s life made better copy than her art. For example, in a discussion of her debut, an Art Digest reporter gave a charming, if simplified, account of the genesis of Moses’ turn to painting, recounting her desire to give the postman “a nice little Christmas gift.” Not only would the dear fellow appreciate a painting, concluded Grandma, but “it was easier to make than to bake a cake over a hot stove.” After quoting from Genauer and other favorable reviews in the New York papers, the report concluded with a folksy supposition: “To all of which Grandma Moses perhaps shakes a bewildered head and repeats, ‘Land’s Sakes’.” Flippantly deeming the artist’s achievements a marker of social change, he noted: “When Grandma takes it up then we can be sure that art, like the bobbed head, is here to stay.”

Urban sophisticates were besotted with the plainspoken, octogenarian farm widow who was scandalized by the “extortion prices” they paid for her work in the Galerie St. Etienne. As Tom Arthur writes in a blog devoted to New York State historical markers:

New Yorkers found that, once wartime gasoline rationing ended, Eagle Bridge made a nice excursion destination for a weekend trip. Local residents were usually willing to talk to outsiders about their local celebrity and give directions to her farm. There they would meet the artist, who was a delight to talk to, and either buy or order paintings from her. Songwriter/impresario Cole Porter became a regular customer, ordering several paintings every year to give to friends around Christmas.

In the two-and‑a half decades between picking her paintbrush back up and her death at the age of 101, she produced over 1600 images, always starting with the sky and moving downward to depict tidy fields, well kept houses, and tiny, hard working figures coming together as a community. In the above documentary she alludes to other artists known to depicting “trouble”… such as livestock busting out of their enclosures.

She preferred to document scenes in which everyone was seen to be behaving.

Remarkably, MoMA exhibited Grandma Moses’ work at the same time as Picasso’s Guernica.

In a land and in a life where a woman can grow old with fearlessness and beauty, it is not strange that she should become an artist at the end. — poet Archibald MacLeish

Hmm.

Read Judith Stein’s fascinating essay in its entirety here.

See more of Grandma Moses’ work here, and her portrait on TIME magazine in 1953.

Related Content

How Leo Tolstoy Learned to Ride a Bike at 67, and Other Tales of Lifelong Learning

Free Art & Art History Courses

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Why Dutch & Japanese Cities Are Insanely Well Designed (and American Cities Are Terribly Designed)

Pity the United States of America: despite its economic, cultural, and military dominance of so much of the world, it struggles to build cities that measure up with the capitals of Europe and Asia. The likes of New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago offer abundant urban life to enjoy, but also equally abundant problems. Apart from the crime rates for which American cities have become fairly or unfairly notorious, there’s also the matter of urban design. Simply put, they don’t feel as if they were built very well, which any American will feel after returning from a trip to Amsterdam or Tokyo — or after watching the videos on those cities by Danish Youtuber OBF.

In Amsterdam, OBF says, “commuters will use their bikes to get to and enter transit stations, where they simply park their bikes in these enormous bike-parking garages. Then they’ll travel on either a bus, tram, or train to their final destination, but most of the time, the fastest and most convenient option is simply taking the bike to the final destination.”

Near-impossible to imagine in the United States, this prevalence of cycling is a reality in not just the Dutch capital but also in other cities across the country, which boasts 32,000 kilometers of bike lanes in total. And those count as only one of the infrastructural glories covered in OBF’s video “Why the Netherlands Is Insanely Well Designed.”

Tokyo, too, has its fair share of cyclists. Whenever I’m over there, I take note of all the well-dressed moms biking their young children to school in the morning, who cut figures in the starkest possible contrast to their American equivalents. But what really underlies the Japanese capital’s distinctively intense urbanism, literally as well as figuratively, is its network of subway trains. OBF takes the precision-engineered efficiency and the impeccable maintenance of this system as his main subject in “Why Tokyo Is Insanely Well Designed.” But enough about good city design; what accounts for bad city design, especially in a rich country like the U.S.?

OMF has an answer in one word: parking. Philadelphia, for example, supplies its 1.6 million people with 2.2 million parking spaces. The consequent deformation of the city’s built environment, clearly visible in aerial footage, both symbolizes and perpetuates the hegemony of the automobile. That same condition once afflicted the European and Asian cities that have since designed their way out of it and then some. While “some people might think it’s nearly impossible to implement these methods into other countries,” says OBF, they “can be replicated any place in the world if the people and leadership are willing to collaborate and listen to one another, and invest in infrastructure that is people‑, environment‑, and future-centered.” As an American living in a non-American city, I hereby invite him to come have a ride on the Seoul Metro.

Related content:

Why Public Transit Sucks in the United States: Four Videos Tell the Story

Why Europe Has So Few Skyscrapers

Leonardo da Vinci Designs the Ideal City: See 3D Models of His Radical Design

The Utopian, Socialist Designs of Soviet Cities

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The Models for “American Gothic” Pose in Front of the Iconic Painting (1942)

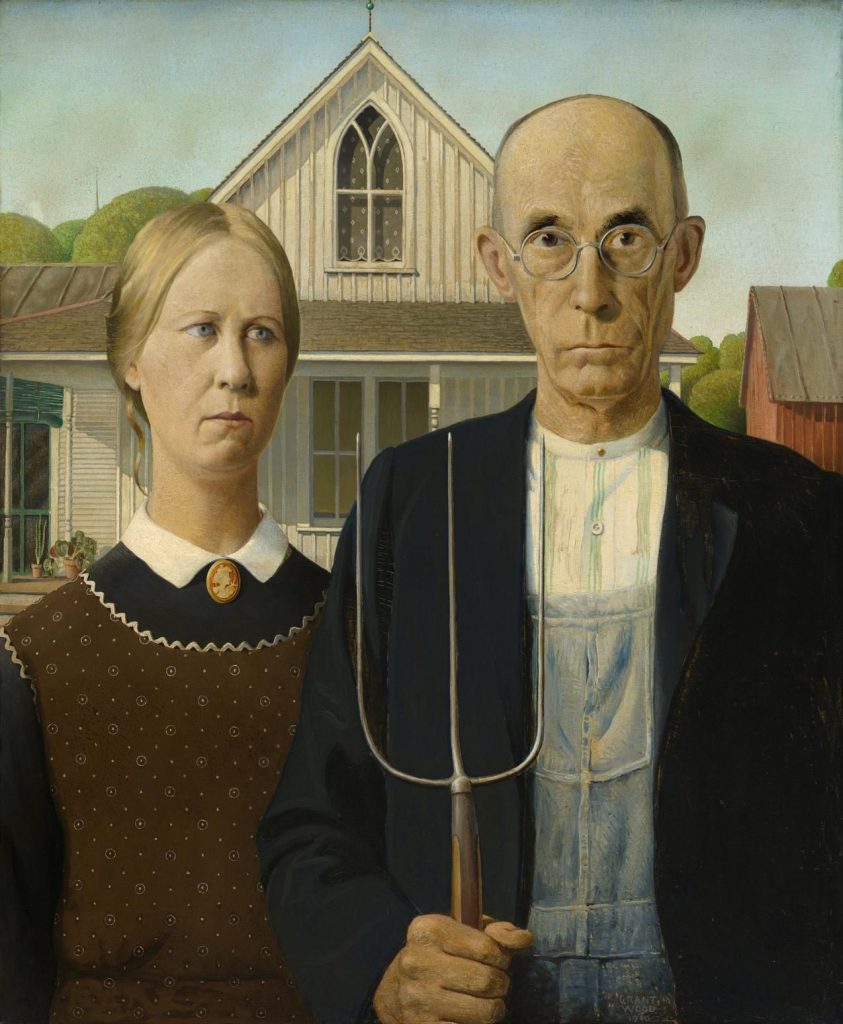

Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” now hangs at the Art Institute of Chicago. And on the museum’s website you’ll find a little background information introducing you to the iconic 1930 painting:

The impetus for the painting came while Wood was visiting the small town of Eldon in his native Iowa. There he spotted a little wood farmhouse, with a single oversized window, made in a style called Carpenter Gothic. [See it here.] “I imagined American Gothic people with their faces stretched out long to go with this American Gothic house,” he said. He used his sister and his dentist as models for a farmer and his daughter, dressing them as if they were “tintypes from my old family album.” The highly detailed, polished style and the rigid frontality of the two figures were inspired by Flemish Renaissance art, which Wood studied during his travels to Europe between 1920 and 1926. After returning to settle in Iowa, he became increasingly appreciative of midwestern traditions and culture, which he celebrated in works such as this. American Gothic, often understood as a satirical comment on the midwestern character, quickly became one of America’s most famous paintings and is now firmly entrenched in the nation’s popular culture. Yet Wood intended it to be a positive statement about rural American values, an image of reassurance at a time of great dislocation and disillusionment. The man and woman, in their solid and well-crafted world, with all their strengths and weaknesses, represent survivors.

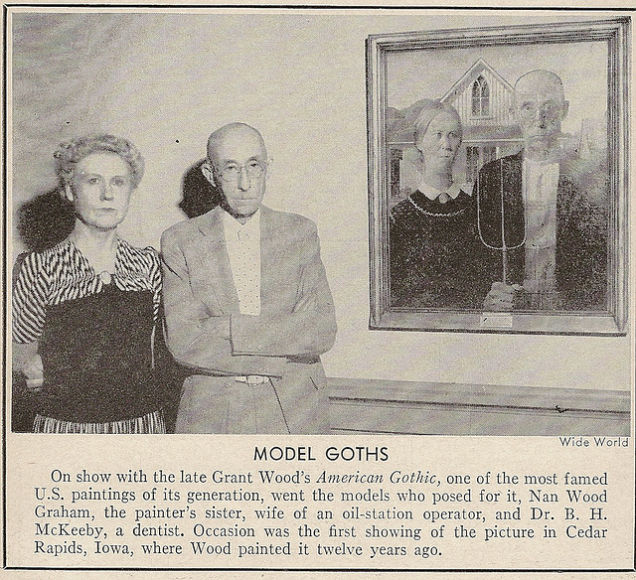

Above, you can see Wood’s sister and dentist–otherwise known as Nan Wood Graham and Dr. B.H. McKeeby–posing in front of “American Gothic” in 1942. That’s when the painting first went on display in its hometown, Cedar Rapids, Iowa. It’s a fairly meta moment. Graham and McKeeby look downright dour in the picture, just as in the painting.

Grant Wood died of pancreatic cancer in ’42, and his sister eventually moved to Northern California, where she became the caretaker of his legacy. She did, after all, owe him a debt. “Grant made a personality out of me,” she said. “I would have had a very drab life without [American Gothic].”

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Whitney Museum Puts Online 21,000 Works of American Art, By 3,000 Artists

Smithsonian Digitizes & Lets You Download 40,000 Works of Asian and American Art

Read More...An Introduction to Chinoiserie: When European Monarchs Tried to Build Chinese Palaces, Houses & Pavilions

Today it would be viewed as cultural appropriation writ large, but when Louis XIV ordered the construction of a 5‑building pleasure pavilion inspired by the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing (a 7th Wonder of the World few French citizens had viewed in person) as an escape from Versailles, and an exotic love nest in which to romp with the Marquise de Montespan, he ignited a craze that spread throughout the West.

Chinoiserie was an aristocratic European fantasy of luxurious Eastern design, what Dung Ngo, founder of AUGUST: A Journal of Travel + Design, describes as “a Western thing that has nothing to do with actual Asian culture:”

Chinoiserie is a little bit like chop suey. It was wholesale invented in the West, based on certain perceptions of Asian culture at the time. It’s very watered down.

And also way over the top, to judge by the rapturous descriptions of the interiors and gardens of Louis XIV’s Trianon de Porcelaine, which stood for less than 20 years.

Image by Hervé Gregoire, via Wikimedia Commons

The blue-and-white Delft tiles meant to mimic Chinese porcelain swiftly fell into disrepair and Madame de Montespan’s successor, her children’s former governess, the Marquise de Maintenon, urged Louis to tear the place down because it was “too cold.”

Her lover did as requested, but elsewhere, the West’s imagination had been captured in a big way.

The burgeoning tea trade between China and the West provided access to Chinese porcelain, textiles, furnishings, and lacquerware, inspiring Western imitations that blur the boundaries between Chinoiserie and Rococo styles

This blend is in evidence in Frederick the Great’s Chinese House in the gardens of Sanssouci (below).

Image by Johann H. Addicks, via Wikimedia Commons

Dr Samuel Wittwer, Director of Palaces and Collections at the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation, describes how the gilded figure atop the roof “is a mixture of the Greek God Hermes and the Chinese philosopher Confucius:”

His European face is more than just a symbol of intellectual union between Asia and Europe…The figure on the roof has an umbrella, an Asian symbol of social dignity, which he holds in an eastern direction. So the famous ex oriente lux, the good and wise Confucian light from the far east, is blocked by the umbrella. Further down, we notice that the foundations of the building seem to be made of feathers and the Chinese heads over the windows, resting on cushions like trophies, turn into a monkey band in the interior. The frescoes in the cupola mainly depict monkeys and parrots. As we know, these particular animals are great imitators without understanding.

Frederick’s enthusiasm for chinoiserie led him to engage architect Carl von Gontard to follow up the Chinese House with a pagoda-shaped structure he named the Dragon House (below) after the sixteen creatures adorning its roof.

Image by Rigorius, via Wikimedia Commons

Dragons also decorate the roof of the Great Pagoda in London’s Kew Gardens, though the gilded wooden originals either succumbed to the elements or were sold off to settle George IV’s gambling debts in the late 18th century.

Image by MX Granger, via Wikimedia Commons

There are even more dragons to be found on the Chinese Pavilion at Drottningholm, Sweden, an architectural confection constructed by King Adolf Fredrik as a birthday surprise for his queen, Louisa. The queen was met by the entire court, cosplaying in Chinese (or more likely, Chinese-inspired) garments.

Not to be outdone, Russia’s Catherine the Great resolved to “capture by caprice” by building a Chinese Village outside of St. Petersburg.

Image by Макс Вальтер, via Wikimedia Commons

Architect Charles Cameron drew up plans for a series of pavilions surrounding a never-realized octagonal-domed observatory. Instead, eight fewer pavilions than Cameron originally envisioned surround a pagoda based on one in Kew Gardens.

Having survived the Nazi occupation and the Soviet era, the Chinese Village is once again a fantasy plaything for the wealthy. A St. Petersburg real estate developer modernized one of the pavilions to serve as a two-bedroom “weekend cottage.”

Given that no record of the original interiors exists, designer Kirill Istomin wasn’t hamstrung by a mandate to stick close to history, but he and his client still went with “numerous chinoiserie touches” as per a feature in Elle Decor:

Panels of antique wallpapers were framed in gilded bamboo for the master bedroom, and vintage Chinese lanterns, purchased in Paris, hang in the dining and living rooms. The star pieces, however, are a set of 18th-century porcelain teapots, which came from the estate of the late New York socialite and philanthropist Brooke Astor.

Explore cultural critic Aileen Kwun and the Asian American Pacific Islander Design Alliance’s perspective on the still popular design trend of chinoiserie here.

h/t Allie C!

Related Content

How the Ornate Tapestries from the Age of Louis XIV Were Made (and Are Still Made Today)

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Kickstarter: the Future of Self-Publishing?

We all know where books come from: a human and a muse meet, fall in love, and two months to twenty years later, a book is born. Then, as with other varieties of babies, the sleepless nights start as a writer searches for a home for the book, collecting rejections like badges of honor, testaments to determination.

We all know where books come from: a human and a muse meet, fall in love, and two months to twenty years later, a book is born. Then, as with other varieties of babies, the sleepless nights start as a writer searches for a home for the book, collecting rejections like badges of honor, testaments to determination.

Well, that was the old-fashioned way. We’ve all heard how the internet has leveled the playing field, allowing anybody to publish work and find an audience. However, this easier path to publication hasn’t necessarily solved an even older writer’s conundrum: How to pay for it.

That is, how to make enough money to sustain yourself as you write (day jobs aside). And so writers must become even wilier. Though you may make money from the sale of a book, how do you fund yourself before the book?

Seth Harwood, the author of three books, is at the front of the movement to find alternate and creative ways of not only reaching audiences, but pursuing the writing life. Since graduating from the Iowa Writers Workshop in 2002, Harwood has built up a loyal fan base—his “Palms Mamas and Palms Daddies” (named for one of his protagonists, Jack Palms)—through social media and free podcasting. Harwood is sustaining a writing life along a path that is likely to be more and more common for writers.

After offering his first novel, Jack Wakes Up, as a free audiobook, Harwood published it in paperback with Breakneck Books in 2008. The Amazon sales, pushed by Palms Mamas and Palms Daddies, landed the book in #1 in Crime/Mystery and #45 overall, bringing the attention of Random House, who re-published the book one year later.

Looking outside mainstream avenues, Harwood secured funding for publication of his next venture, Young Junius, with Tyrus Books by preselling signed copies through Paypal—before the books existed in physical form. And now he is one of the early adopters of using Kickstarter to pay for the gestation and birth of not one book—but five previously-written works in the next six months–as he puts it, “raising the fixed costs of bringing these books to the marketplace.” His Kickstarter campaign based around This Is Life, the sequel to Jack Wakes Up was—impressively—fully funded within 25 hours—and with a few days still left to go, it has exceeded the original goal by over $2000.

What can a writer offer besides an autographed copy of the to-be-written book, or a mention in the acknowledgements? For Harwood’s project, the pledges range from a dollar to $999, with thank-yous spanning from the aforementioned to—at the $999 end—an original novella written according to the donor’s wishes and published as a one-off hardcover.

As more and more writers become cynical about the mainstream publishing industry, and the limits it places on writers, and as the internet breaks down barriers between writers and readers, alternate paths of drawing audiences to the writing/publishing process may become more and more popular. In none other than the New York Times Book Review, Neal Pollack recently declared his intention to self-publish his next book using Kickstarter to generate his fixed costs and “an advance,” and last week bestseller Paulo Coelho discussed his decision to offer his novels for free online. (You can find free ebooks by Coelho here.)

Indeed, now more than ever, it seems essential for authors to meet readers at least half-way. Harwood considers himself an “author-preneur,” developing new business models as he publishes his books. As he sees it, innovation comes much more easily to an author acting alone, than to a large publishing company or big corporation. He aims for the new models as he sees them developing, knowing he’s got to go out and find readers himself. As Coelho declares, “The ivory tower does not exist anymore.”

This post was contributed by Shawna Yang Ryan. Her novel Water Ghosts was a finalist for the 2010 Asian American Literary Award. In 2012, she will be the Distinguished Writer in Residence at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa.

Read More...Humans First Started Enjoying Cannabis in China Circa 2800 BC

Judging by how certain American cities smell these days, you’d think cannabis was invented last week. But that spike in enthusiasm, as well as in public indulgence, comes as only a recent chapter in that substance’s very long history. In fact, says the presenter of the PBS Eons video above, humanity began cultivating it “in what’s now China around 12,000 years ago. This makes cannabis one of the single oldest known plants we domesticate,” even earlier than “staples like wheat, corn, and potatoes.” By that time scale, it wasn’t so long ago — four millennia or so — that the lineages used for hemp and for drugs genetically separated from each other.

The oldest evidence of cannabis smoking as we know it, also explored in the Science magazine video below, dates back 2,500 years. “The first known smokers were possibly Zoroastrian mourners along the ancient Silk Road who burned pot during funeral rituals,” a proposition supported by the analysis of the remains of ancient braziers found at the Jirzankal cemetery, at the foot of the Pamir mountains in western China. “Tests revealed chemical compounds from cannabis, including the non-psychoactive cannabidiol, also known as CBD” — itself reinvented in our time as a thoroughly modern product — and traces of a THC byproduct called cannabinol “more intense than in other ancient samples.”

What made the Jirzankal cemetery’s stash pack such a punch? “The region’s high altitude could have stressed the cannabis, creating plants naturally high in THC,” writes Science’s Andrew Lawler. “But humans may also have intervened to breed a more wicked weed.” As cannabis-users of the sixties and seventies who return to the fold today find out, the weed has grown wicked indeed over the past few decades. But even millennia ago and half a world away, civilizations that had incorporated it for ritualistic use — or as a medical treatment — may already have been agriculturally guiding it toward greater potency. Your neighborhood dispensary may not be the most sublime place on Earth, but at least, when next you pay it a visit, you’ll have a sound historical reason to cast your mind to the Central Asian steppe.

Related content:

The Drugs Used by the Ancient Greeks and Romans

Algerian Cave Paintings Suggest Humans Did Magic Mushrooms 9,000 Years Ago

Carl Sagan on the Virtues of Marijuana (1969)

Watch High Maintenance: A Critically-Acclaimed Web Series About Life & Cannabis

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The History of Cartography, the “Most Ambitious Overview of Map Making Ever,” Is Free Online

FYI: The University of Chicago Press has made available online — at no cost –five volumes of The History of Cartography. Or what Edward Rothstein, of The New York Times, called “the most ambitious overview of map making ever undertaken.” He continues:

People come to know the world the way they come to map it—through their perceptions of how its elements are connected and of how they should move among them. This is precisely what the series is attempting by situating the map at the heart of cultural life and revealing its relationship to society, science, and religion…. It is trying to define a new set of relationships between maps and the physical world that involve more than geometric correspondence. It is in essence a new map of human attempts to chart the world.

If you head over to this page, you will see links (in the left margin) to five volumes available in a free PDF format. The image above, appearing in Vol. 2, dates back to 1534. Created by Oronce Fine, the first chair of mathematics in the Collège Royal (aka the Collège de France), the map features the world drawn in the shape of a heart. A pretty beautiful design. Below you can find links to the individual volumes available online.

Volume 1

Volume 2: Book 1

Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies

Volume 2: Book 2

Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies

Volume 2: Part 3

Volume 3:

Cartography in the European Renaissance: Part 1

Cartography in the European Renaissance, Part 2

Volume 4:

Cartography in the European Enlightenment

Volume 5:

Cartography in the Nineteenth Century, Forthcoming

Volume 6:

Cartography in the Twentieth Century

If you buy any of the printed versions on Amazon, each edition will cost you $400-$500. As beautiful as the book probably is, you’ll likely appreciate this free digital offering.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Download 91,000 Historic Maps from the Massive David Rumsey Map Collection

40,000 Early Modern Maps Are Now Freely Available Online (Courtesy of the British Library)

Behold an Incredibly Detailed, Handmade Map Of Medieval Trade Routes

The World Map That Introduced Scientific Mapmaking to the Medieval Islamic World (1154 AD)

Read More...

Behold the Unique Beauty of Japan’s Artistic Manhole Covers

Visitors to Japan can’t help but be struck by the beauty of its temples, its scenic views, its zen gardens, its manhole covers…

You read that right.

What started as a scheme to get taxpayers on board with pricey rural sewer projects in the 1980s has grown into a countrywide tourist attraction and a matter of civic pride.

Each municipality boasts its own unique manhole cover designs, inspired by specific regional elements.

A community might opt to rep its local floral or fauna, a famous local landmark or festival, an historic event or bit of folklore.

Matsumoto City highlights one of its popular folk craft souvenirs, the colorful silk temari balls that once served as toys for female children and bridal gifts.

Nagoya touts the purity of its water with a water strider — an insect that requires the most pristine conditions to survive.

Hiroshima pays tribute to its baseball team.

Osaka offers a view of its castle surrounded by cherry blossoms.

The proximity of the Sanrio Puroland theme park allows Tama City to lay claim to Hello Kitty and Pokémon-themed lids have sprung up like mushrooms from Tokyo to Okinawa.

Most of Japan’s 15 million artistic manhole covers are monochromatic steel which makes spotting one of the vibrantly colored models even more exciting.

In the fifty some years since their introduction, an entire subculture has emerged. Veteran enthusiast Shoji Morimoto coined the term “manholer” to describe hobbyists participating in this “treasure hunt for adults.”

Remo Camerota documents his obsession in Drainspotting: Japanese Manhole Covers and American traveler Carrie McNinch shares the joy of stumbling across previously unspotted ones in her autobiographical comic series You Don’t Get There From Here.

The ongoing popularity of this officially sanctioned street art is evidenced by the Japanese Society of Manhole Lovers, an annual manhole summit, and tons of collectible trading cards.

Explore a crowdsourced gallery of Japanese manhole covers here.

Related Content

Discover Edo, the Historic Green/Sustainable City of Japan

The Making of Japanese Handmade Paper: A Short Film Documents an 800-Year-Old Tradition

Download Classic Japanese Wave and Ripple Designs: A Go-to Guide for Japanese Artists from 1903

Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of The East Village Inky zine and nine books, including, most recently Creative, Not Famous. Follow her @Ayun-Halliday

Read More...Why 99% Of Smithsonian’s Specimens Are Hidden In High-Security

Museums are the memory of our culture and they’re the memory of our planet. — Dr. Kirk Johnson, Director, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

For many of us natural history museums are emblematic of school field trips, or rainy day outings with (or as) children.

There’s always something to be gleaned from the reconstructed dinosaur skeletons, dazzling minerals, and 100-year-old specimens on display.

The educational prospects are even greater for research scientists.

The above entry in Business Insider’s Big Business series takes us behind the scenes of the Smithsonian Natural History Museum, a federally-funded institution where more than 99% of its vast collection is housed in the basement, on upper floors and employees-only wings of exhibition floors, or at an offsite facility in neighboring Maryland.

The latter is poised to provide safe space for more of these treasures as climate change-related flooding poses an increasingly dire threat. The museum’s National Mall location, which draws more than 6 million visitors annually, is now virtually at sea level, and Congress is moving at a pace formerly known as glacial to approve the expensive but necessary structural improvements that would safeguard these precious collections.

The museum currently boasts some 147 million specimens, and is continually adding more, by means of field collections, donations, and purchases made with endowments, though as a non-profit institution, it’s rarely able to outbid deep-pocketed private collectors at auctions of hot-ticket items like large dinosaur bones.

The Division of Birds’ daily mail brings samples of “snarge” — whatever’s left over when a bird makes impact with an aircraft.

Upon arrival at the Smithsonian, whatever its size or market value, every item is subjected to a process of inspection known as “accessioning”.

After that, it is meticulously cleaned.

Beetles in an offsite Osteo Prep Lab get to work on residual organic materials like skin and tissue.

Human experts use a handheld air scrape tool to incrementally separate fossils from the rocky matrix in which they were discovered

The goal is permanent storage state.

Geological specimens are classified according to Dana’s System of Mineralogy and stored in drawers. High-value items are assigned to the Blue Room or the Gem Vault.

Bones that are looking to spend the better part of eternity on a shelf are fitted for custom fiberglass and plastic cradles to protect against pests, moisture, and gravity-related stress fractures.

The Department of Entomology dries and pins incoming insects, arachnids, and myriapods, and stores them in hydraulic carriages.

Mammals, reptiles, fish and birds are stuffed or pickled in alcohol.

Many items in the museum’s collection date back to the early 20th century.

These days, staff strive to preserve as much as they can, using every tool and scientific advancement at their disposal. As ornithologist and feather identification specialist Carla Dove, states, “It’s our responsibility to do as much as we can with the specimen if we’re going to take it from the wild for research.”

These careful preparations ensure that the world’s largest natural history collection can continue to serve as a living library for thousands of visiting scientists…climate change permitting.

Access to the Museum of Natural History’s collections and databases result in the publication of hundreds of research papers and the identification of hundreds of new species every year.

In addition to providing valuable intelligence for research initiatives on such topics as disease transmission, volcanic activity, and of course, the effects of bird strikes on airplanes, museum staff is working toward a goal of preserving each item with a digital scan — 9 million and counting…

Related Content

The Smithsonian Puts 2.8 Million High-Res Images Online and Into the Public Domain

Smithsonian Digitizes & Lets You Download 40,000 Works of Asian and American Art

The Smithsonian Picks “101 Objects That Made America”

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...