I have no politics, I observe. I have no sides except the side of the human spirit, which after all does sound rather shallow, like a pitchman, but which means mostly my spirit, which means yours too, for if I am not truly alive, how can I see you?

—Charles Bukowski, Notes of. Dirty Old Man

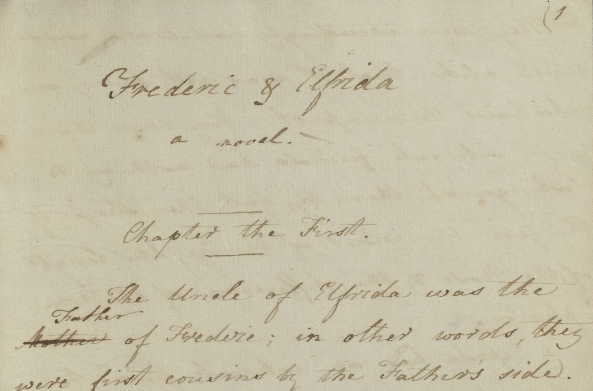

In Notes of a Dirty Old Man, his weekly column for the underground L.A. newspaper Open City, Charles Bukowski became the common man’s philosopher, issuing profundities amidst wild vulgarities and proving that he did, in fact, have a politics, as much as he had theories and contrarian half-thoughts and opinions aplenty. He took sides when it came to literature, at least—the side of Celine, Dostoevsky, and Camus, for example, against Faulkner, Shakespeare, and George Bernard Shaw (“the most overblown fantasy of the Ages”).

Bukowski had no room for cool appreciation or mild preference. With him, as with Catullus, life was love and hate. Get him talking on any subject and those loves and hates would emerge, as would his ideas about matters of most consequence: life, death, drinking, sex, and, of course, writing. In the interview clip above, for example, Bukowski is asked if he fears death. He answers, “No, in fact, I almost feel good at the approach of death.” This becomes a meditation on repetition and dullness, and on the “juice” that a good life—and good writing—requires.

…. You see, as you live many years, things take on a repeat…. You understand? You keep seeing the same thing over and over again… so you get a little bit tired of life. So as death comes, you almost say, okay, baby, it’s time, it’s good.

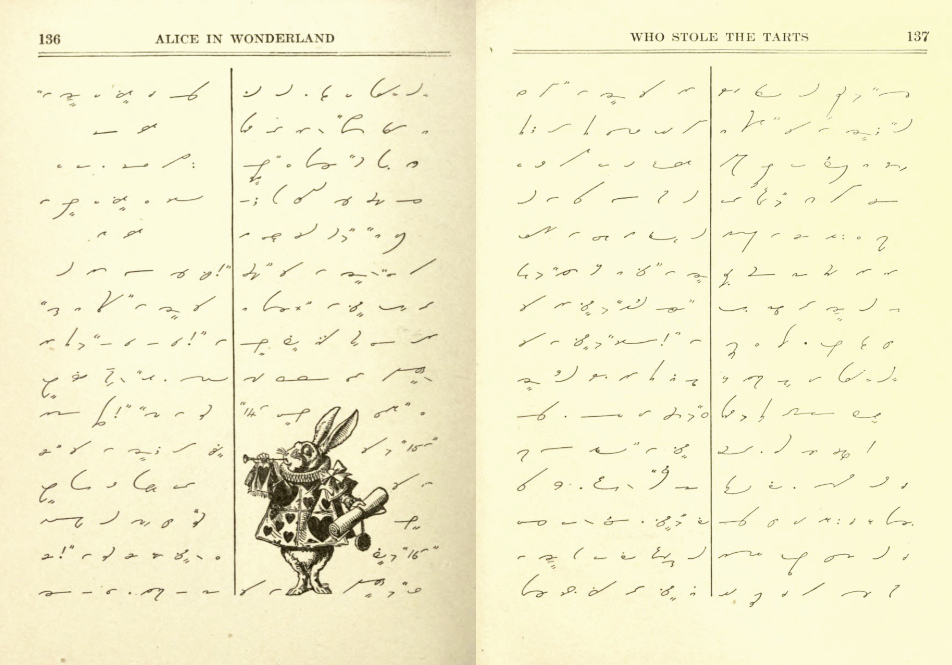

The answer puts the interviewer in mind of Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, which sends Bukowski on one of his signature cranky critiques, also an introduction to his theory of prose, which can be summed up in just three syllables, “BIM BIM BIM!”—the sound he makes to show the “quickness” of a well-written line. Good writing needs “pace,” “life,” and “sunlight.” “Each line,” he says, “must be full of a delicious little juice, they must be full of power, they must make you like to turn a page, bim bim bim!” Writing like Lowry’s, he says, is “too leisurely.” There’s too much setup, too little payoff.

He may seem unfair to Lowry, but most writers bore Bukowski. After pages of tedious buildup, “when they get to the grand emotion, there isn’t any,” he says. Bukowski has never been one for subtlety, but no one can say his writing lacks “juice” or grand emotion. On the contrary, he endears himself to so many aspiring writers (or aspiring male writers, in any case) because his poetry and prose are so electrifyingly alive. He had a limited range of subjects, mostly confined to his own thoughts, feelings, and drunken misadventures. Yet the voice that carries us through his violently funny tales and reveries, wicked and maudlin and tender by turns, seems capable of limitless invention.

“Writing must never be boring,” says Bukowski. He set a high bar, and he met it. As writers, we need not live his life to do the same. But we must each be “truly alive” in our own way to make our lines go bim bim bim. “Each line,” he says, “must be an entity unto itself.”

Related Content:

Charles Bukowski Reads His Poem “The Secret of My Endurance”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness