Tim Ferriss: Are there any other rules or practices that you also hold sacred or important for your writing process?

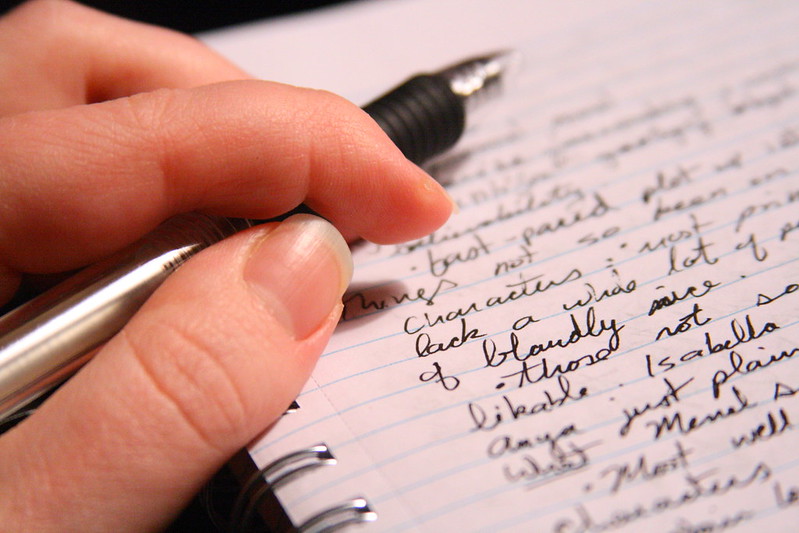

Neil Gaiman: Some of them are just things for me. For example, most of the time, not always, I will do my first draft in fountain pen, because I actually enjoy the process of writing with a fountain pen. I like the feeling of fountain pen. I like uncapping it. I like the weight of it in my hand. I like that thing, so I’ll have a notebook, I’ll have a fountain pen, and I’ll write. If I’m doing anything long, if I’m working on a novel, for example, I will always have two fountain pens on the go, at least, with two different colored inks, at least, because that way I can see at a glance, how much work I did that day. I can just look down and go, “Look at that! Five pages in brown. How about that? Half a page in black. That was not a good day. Nine pages in blue, cool, what a great day.”

You can just get a sense of are you working, are you making forward progress? What’s actually happening. I also love that because it emphasizes for me that nobody is ever meant to read your first draft. Your first draft can go way off the rails, your first draft can absolutely go up in flames, it can — you can change the age, gender, number of a character, you can bring somebody dead back to life. Nobody ever needs to know anything that happens in your first draft. It is you telling the story to yourself.

Then, I’ll sit down and type. I’ll put it onto a computer, and as far as I’m concerned, the second draft is where I try and make it look like I knew what I was doing all along.

Tim Ferriss: Do you edit, then, as you’re looking or translating from the first draft on the page to the computer, or do you get it all down as is in the computer and then edit —

Neil Gaiman: No, that’s my editing process. I figure that’s my second draft is typing into the computer. Also, I love — backing up a bit here. When I was, what was I? 27, 28? In the days when we were still in typewriters and we were just a handful of people with word processors, which were clunky things with disks which didn’t hold very much and stuff, I edited an anthology and enjoyed editing my anthology.

Most of the stories that came in were about 3,000 words long. Move forward in time, not much, five, six, seven years. Mid ‘90s, everybody is now on computer, and I edited another short story anthology. The stories that were coming in tended to be somewhere between six- and 9,000 words long. They didn’t really have much more story than the 3,000 word ones, and I realized that what was happening is it’s a computer‑y thing, is if you’re typing, putting stuff down is work. If you’ve got a computer, adding stuff is not work. Choosing is work. It expands a bit, like a gas. If you have two things you could say, you say both of them. If you have the stuff you want to add, you add it, and I thought, “Okay, I have to not do that, because otherwise my stuff is going to balloon and it will become gaseous and thin.”

What I love, if I’ve written something on a computer, and I decide to lose a chunk, it feels like I’ve lost work. I delete a page and a half, I feel like there’s a page and half that just went away. That was a page and a half’s worth of work I’ve just lost. If I’ve been writing in a notebook and I’m typing it up, I can look at something and go, “Oh, I don’t need this page and a half.” I leave it out, I just saved myself work, and it feels like I’m treating myself.

I’m just trying to always have in my head the idea that maybe I’m somehow, on some cosmic level, paying somebody by the word in order to be allowed to write, but if they’re there, they should matter, they should mean something. It’s always important to me.

Tim Ferriss: You mentioned distraction earlier and your dangerously adorable son, which I certainly agree with. I had read somewhere, actually, before I get to that, this might seem like a very, very mundane question, but what type of notebooks do you prefer? Are they large legal pads or are they leather bound? What type of notebooks?

Neil Gaiman: When they came out, I really liked — I’ve used a whole bunch of different ones. I bought big drawing ones, which actually turned out to be a bit too big, though I liked how much I could see on the page. Those are the ones I wrote Stardust and American Gods in, big size, but they weren’t terribly portable. I went over to the Moleskines, and I loved them when they first came out, and then they dropped their paper quality. Dropping paper quality doesn’t matter, unless you’re writing in fountain pen, because all of a sudden it’s bleeding through, and all of a sudden you’re writing on one page, leaving a page blank because it’s bled through and then writing on the next page.

Joe Hill, about six or seven years ago, Joe Hill, the wonderful horror fantasy writer, suggested the Leuchtturm to me. My usual notebook right now is a Leuchtturm, because I really like the way you can paginate stuff in them and the thickness of the paper, and they’re just like Moleskines, but the Porsche of Moleskines. They’re just better.

I also have been writing, I wrote The Graveyard Book and I’m writing the current novel in these beautiful books that I bought in a stationery shop in Venice, built into a bridge. Somewhere in Venice there’s a little stationery shop on a bridge, and they have these beautiful leather-bound blank books that just look like hardback books, but they’re blank pages. I wrote The Graveyard Book in one of those. I bought four of them, and now I’m using the next one on the next novel, and it may well go into another one. I’m not sure.

Then, at home, I say at home, my house in Wisconsin, which is where my stuff is, I’ve got my — we live in Woodstock, but I have an entire life’s worth of stuff still sitting in my house in Wisconsin, and it’s become archives. It’s actually kind of fabulous having a house that is an archive, but waiting for me in that house is a book that I bought for myself about 25 years ago, and before I die, I plan to write a novel in it. It’s an accounts book from the mid-19th century. It’s 500 pages long. Every page is numbered. It’s lined with accounts lines, but really faint so it would be nice to write a book in it, and it is engineered so that every single page lies flat.

It’s huge and it’s heavy and it just looks like a book that Dickens or somebody would’ve written a novel in and I’ve just been waiting until I have an idea that is huge and weird and Dickensian enough, and whether or not I actually get to write it in dip pen, I’m not sure, but I definitely want to write it in an old Victorian, something slightly copper plating. One of those old flex nib pens that they stopped making when carbon paper came in, just so I can get that spidery Victorian handwriting.

Tim Ferriss: I’m just imagining you putting pen to the first page. When you finish the first page and what that will feel like. That’s going to be a good day.

Neil Gaiman: It will be either a good day or an incredibly bad day. When you get to the end of the first page, it’s “Oh no! I had this pristine — ” it is the thing that I tell young writers, and by young writers, a young writer can be any age. You just have to be starting out, which is anything you do can be fixed. What you cannot fix is the perfection of a blank page. What you cannot fix is that pristine, unsullied whiteness of a screen or a page with nothing on it, because there’s nothing there to fix.

Tim Ferriss: You mentioned a word, and it might be that I’m a little slow moving because I’m from Long Island, but Leuchtturm? What is that word?

Neil Gaiman: L‑E-I-C‑H, I think it’s T‑U-R‑M, and then 1917, I think is — their Twitter handle is definitely Leuchtturm1917.

Tim Ferriss: Leuchtturm, and I’ll put that in the show notes for folks, so you’ll be able to find it. Since you gave me — I’m not intending to turn this episode into a shopping list, but I’ve never used fountain pens.

Neil Gaiman: Really?

Tim Ferriss: I have not. My assistant, my dear assistant does. She loves using fountain pens. She enjoys the act. I’ve had a few sloppy false starts and then been rather impatient, but if I wanted to give it a shot, are there any particular fountain pens or criteria that you would use in picking a good pen?

Neil Gaiman: The biggest criteria I would use in picking, if you have the choice, is go somewhere like New York’s Fountain Pen Hospital.

Tim Ferriss: Is that a real place?

Neil Gaiman: It’s a real place. It’s called The Fountain Pen Hospital. They sell lots of new pens, they recondition old pens, they look after pens for you. And try them out, because the lovely thing about fountain pens is they are personal. You go, “No, no, no.” And then you find the one. I tend to suggest to people who are just nervously — “I’ve never used a fountain pen, what should I do?” I will point them at Lamy, L‑A-M‑Y, who have some fabulous starter pens, and they’re not very expensive, and they’re good. They do a pen called The Safari, but they have a bunch of good starter pens, and they’re just nice to get into the idea of, “Do I like doing this?”

Let’s see, what am I using right now? What have I got in here? This one here is a Pilot. It’s a Namiki, and it’s a flexing nib ever so slightly when you put down weight on it, the nib will spread. It’s a beautiful, beautiful pen. That one’s a Pilot. I think this one here is the Namiki. It’s really weird because Namiki is Pilot, so I don’t quite understand that.

Tim Ferriss: Maybe it’s a Toyota/Lexus thing?

Neil Gaiman: I think it is. It’s that kinda thing. This one here is called a Falcon, and again, you put a little bit of weight on it, and the line will just spread and thicken, which is part of the fun of fountain pens. I’ll go and play. There’s a lovely Italian one. I’ve got my agent, I did a thing some years ago when I realized that I was losing a lot of actual writing time to signing foreign contracts.

Tim Ferriss: This is for books?

Neil Gaiman: This is for books, or occasionally for stories or things being reprinted around the world. The contracts would come in and there would be big sheaves of them because they get printed all around the world, and foreign contracts, a lot of them you have to sign a lot. You have to do a lot of initialing and I would sit there going, “I have just spent 90 minutes signing a pile of contracts, and I love that I got to sign it, but —” I contacted my agent. I said, “Can I give you power of attorney? Would you mind? Would you just sign these things for me?”

She was like, “Absolutely!” Great. I got her — she’d never used a fountain pen and I got her a fountain pen. I actually went to The New York Fountain Pen Hospital with her, and did the thing of showing her pens, “What do you like?” I got her a Visconti, which are just these lovely Italian pens. Mostly I love, there’s a slightly fetishistic bit of having bottles of beautifully colored ink. When you start talking to fountain pen people, they really — they pretend to be interested in what pen you like, but they don’t care, because they’ve found their own pens that they love.

They say, “What do you use?”

I use Pilot 823s for signing. Actually now, I’ve got a Pilot 823, ’cause it’s just a fantastic signing pen. It’s a workhorse, it keeps going, and I got one in 2012 and it was my signing pen. I signed through Ocean at the End of the Lane. Before the book had come out, I had already pre-signed, written my signature 20,000 times with this pen.

Tim Ferriss: I have some footage of you icing your hand after said signings.

Neil Gaiman: That was a signing tour that I really got into icing my hand and wrist and arm. I did the numbers, and as far as I can tell, I’ve signed about one and a half million signatures with that pen, which remained, and I had to send it off to Pilot at one point, not because the nib was in trouble, because the plunger mechanism was starting to stick, and they fixed it for me and sent it back. Then my three-year-old son found a place behind a cast iron fireplace in our house in Woodstock where if you just insert your father’s Pilot 823 pen, which you have found on the table, just to see if it would go in there, you can actually guarantee that without disassembling the house, we actually have to take the entire house apart to uninstall a cast iron fireplace from 1913 to get at the pen. That pen now has been given as a sacrifice to the house gods, so I need to get a new one.

Tim Ferriss: Its strikes me, at least it seems as we’re talking that many of the decisions you’ve made, the tools you’ve found and enlisted, act to make not writing unappealing, or at least boring after five minutes, and to enhance the act of writing to make it something that is enjoyable. I don’t know if that’s true.

Neil Gaiman: That is true, but they also exist for another reason, which is kind of weird, which is to try and trivialize what I’m doing and not make it important and freighted down with weight, because that paralyzes me. When I started writing I had a typewriter. It was a manual typewriter. When I sold my first book, I had the money to buy an electric typewriter.

Tim Ferriss: What was that first book?

Neil Gaiman: Gosh. I actually don’t remember whether I bought the electric typewriter with the money from a book called Ghastly Beyond Belief, a book of science fiction and fantasy quotations I did with Kim Newman, or whether it was for the Duran Duran biography that I did. Either way, I was just 23. What I would do back then is I would do my rough draft on scrap paper, single spaced so that it couldn’t be used, and also so that I could get as many words on. Paper was expensive. I could always do that. I remember the joy of getting my first computer, and just the idea that I wasn’t making paper dirty. Nothing mattered until I pressed print, and that was absolutely and utterly liberating.

And then, a decade on, picking up a notebook, it was for Stardust, which I’d decided that I wanted the rhythms of Stardust to be very antiquated rhythms, and I thought there’s probably a difference to the way that one writes with a fountain pen. 17 century writing, 17th, 18th century writing, you notice tends to go in very, very long sentences and long paragraphs. My theory about this is that one reason why you get this is because you’’re using dip pens, and if you pause, they dry up. You just have to keep going. It forces you to do a kind of writing where you’re going for a very long sentence and you’re going to go for a long paragraph and you’re going to keep moving in this thing, and you’re thinking ahead.

If you’re writing on a computer, you’ll think of the sort of thing that you mean, and then write that down and look at it and then fiddle with it and get it to be the thing that you mean. If you’re writing in fountain pen, if you do that, you just wind up with a page covered with crossings out, so it’s actually so much easier to just think a little bit more. You slow up a bit, but you’re thinking the sentence through to the end, and then you start writing.

You write that, and then you pause and then you write the next one. At least that was the way that I hypothesized that I might be writing, and I wanted Stardust to feel like it had been written in the late 1920s. I thought to do that I should probably get myself a fountain pen and a book, so that was how I started writing that. Again, what I loved was suddenly feeling liberated. Saying, “Ah, I’m not actually making words that are not going down in phosphor on a computer screen.”