Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Each writer’s process is a personal relationship between them and the page—and the desk, room, chair, pens or pencils, typewriter or laptop, turntable, CD player, streaming audio… you get the idea. The kind of music suitable for listening to while writing (I, for one, cannot write to music with lyrics) varies so widely that it encompasses everything and nothing. Silence can be a kind of music, too, if you listen closely.

Far more interesting than trying to make general rules is to examine specific cases: to learn the music a writer hears when they compose, to divine the rhythms that animated their prose.

There are almost always clues. Favorite albums left behind in writing rooms or written about with high praise. Sometimes the music enters into the novel, becomes a character itself. In James Baldwin’s Another Country, music is a powerful procreative force:

The beat: hands, feet, tambourines, drums, pianos, laughter, curses, razor blades: the man stiffening with a laugh and a growl and a purr and the woman moistening and softening with a whisper and a sigh and a cry. The beat—in Harlem in the summertime one could almost see it, shaking above the pavements and the roof.

Baldwin finished his first novel, 1953’s Go Tell It on the Mountain, not in Harlem but in the Swiss Alps, where he moved “with two Bessie Smith records and a typewriter under his arm,” writes Valentina Di Liscia at Hyperallergic. He “largely attributes” the novel “to Smith’s bluesy intonations.” As he told Studs Terkel in 1961, “Bessie had the beat. In that icy wilderness, as far removed from Harlem as anything you can imagine, with Bessie and me… I began…”

Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi, a curator at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, has gone much further, digging through all the deep cuts in Baldwin’s collection while living in Provence and trying to recapture the atmosphere of Baldwin’s home, “those boisterous and tender convos when guests like Nina Simone, Stevie Wonder… Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison” stopped by for dinner and debates. He first encountered the records in a photograph posted by La Maison Baldwin, the organization that preserves his house in Saint-Paul de Vence in the South of France. “I latched onto his records, their sonic ambience,” Onyewuenyi says.

“In addition to reading the books and essays” that Baldwin wrote while living in France, Onyewuenyi discovered “listening to the records was something that could transport me there.” He has compiled Baldwin’s collection into a 478-track, 32-hour Spotify playlist, Chez Baldwin. Only two records couldn’t be found on the streaming platform, Lou Rawls’ When the Night Comes (1983) and Ray Charles’s Sweet & Sour Tears (1964). Listen to the full playlist above, preferably while reading Baldwin, or composing your own works of prose, verse, drama, and email.

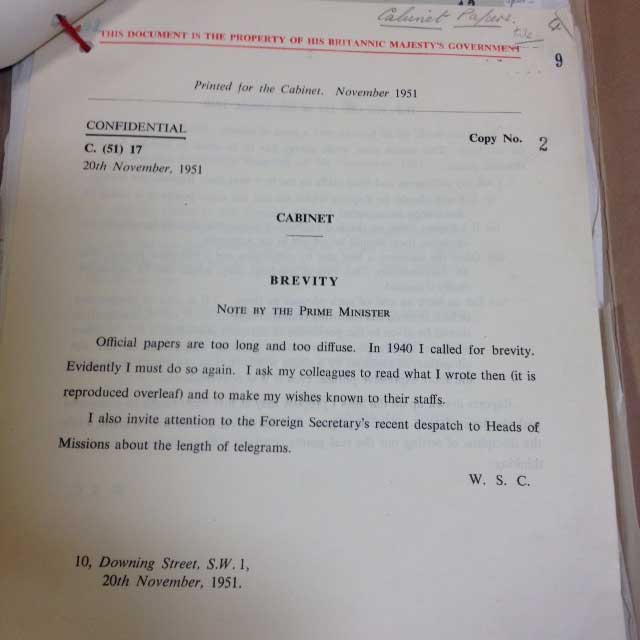

“The playlist is a balm of sorts when one is writing,” Onyewuenyi told Hyperallergic. “Baldwin referred to his office as a ‘torture chamber.’ We’ve all encountered those moments of writers’ block, where the process of putting pen to paper feels like bloodletting. That process of torture for Baldwin was negotiated with these records.”

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

The Best Music to Write By: Give Us Your Recommendations

The Best Music to Write By, Part II: Your Favorites Brought Together in a Special Playlist

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.