He would be a very simple person, and quite a stranger to the oracles of Thamus or Ammon, who should leave in writing or receive in writing any art under the idea that the written word would be intelligible or certain. — Socrates

The transmission of truth was at one time a face-to-face business that took place directly between teacher and student. We find ancient sages around the world who discouraged writing and privileged spoken dialogue as the best way to communicate. Why is that? Socrates himself explained it in Plato’s Phaedrus, with a myth about the origin of writing. In his story, the Egyptian god Thoth devises the various means of communication by signs and presents them to the Egyptian god-king Thamus, also known as Ammon. Thamus examines them, praising or disparaging each in turn. When he gets to writing, he is especially put out.

“O most ingenious Theuth,” says Thamus (in Benjamin Jowett’s translation), “you who are the father of letters, from a paternal love of your own children have been led to attribute to them a quality which they cannot have; for this discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth.”

Other technologies of communication like Incan khipu have the quality of “embeddedness,” says YouTuber NativeLang above, in an animated history of writing that begins with the myth of “Thoth’s Pill.” That is to say, such forms are inseparable from the material context of their origins. Writing is unique, fungible, alienable, and alienating. Its greatest strength — the ability to communicate across distances of time and space — is also its weakness since it separates us from each other, requiring us to memorize complex systems of signs and interpret an author’s meaning in their absence. Socrates criticizes writing because “it will de-embed you.”

The irony of Socrates’ critique (via Plato) is that “it comes to us via text,” notes Bear Skin Digital. “We enjoy it and think about it purely because it is recorded in writing.” What’s more, as Phaedrus says in response, Socrates’ story is only a story. “You can easily invent tales of Egypt, or of any other country.” To which Socrates replies that a truth is a truth, no matter who says it, or how we happen to hear it. Is it so with writing? Does its ambiguity render it useless? Are written works like orphans, as Socrates characterizes them? “If they are maltreated or abused, they have no parents to protect them; and they cannot protect or defend themselves….”

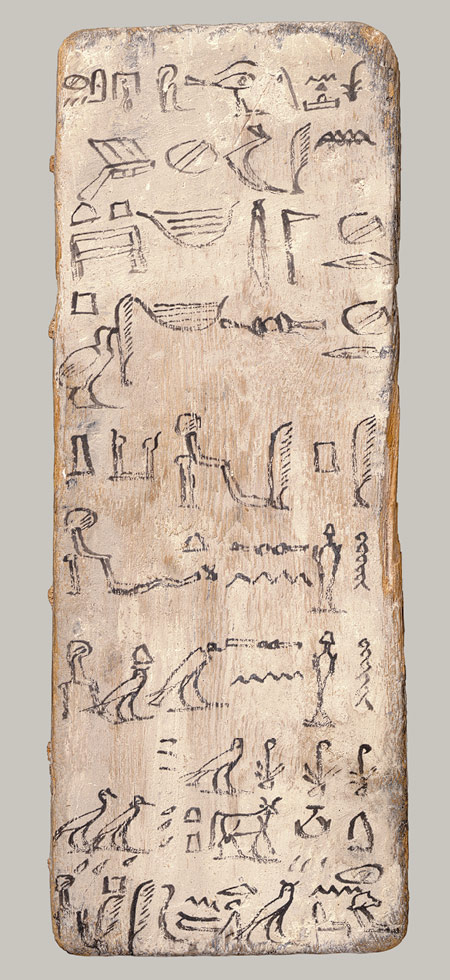

It’s a little too late to decide if we’re better off without the written word, so many millennia after writing grew out of pictographs, or “proto-writing” and into ideographs, logographs, rebuses, phonetic alphabets, and more. Watch the full animated history of writing above and, then, by all means, close your browser and go have a long conversation with someone face-to-face.

Related Content:

40,000-Year-Old Symbols Found in Caves Worldwide May Be the Earliest Written Language

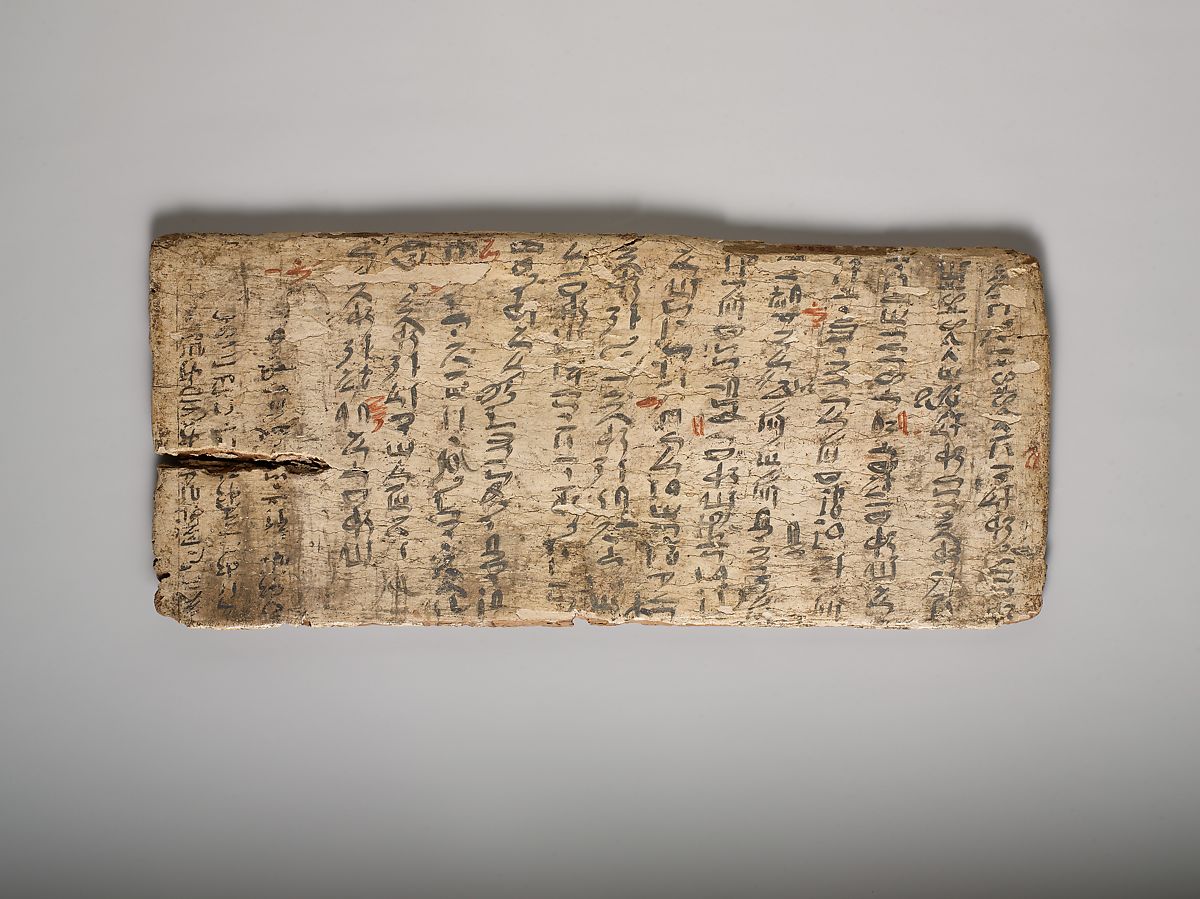

A 4,000-Year-Old Student ‘Writing Board’ from Ancient Egypt (with Teacher’s Corrections in Red)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness