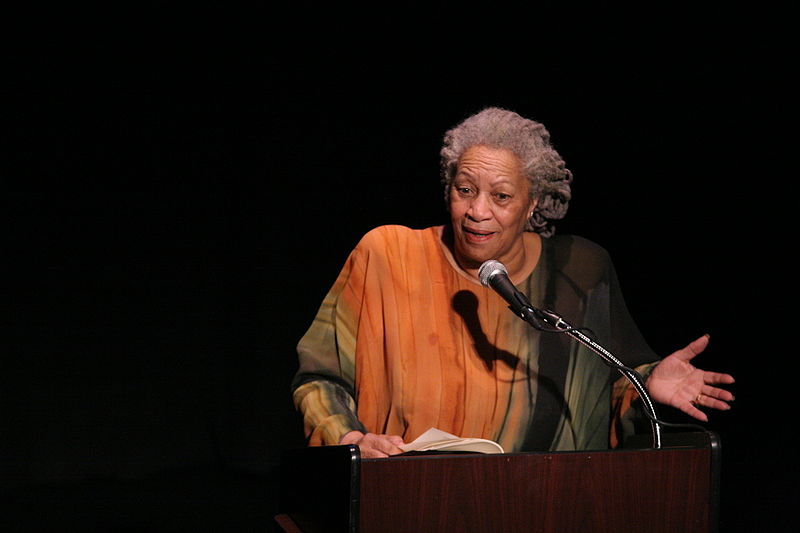

Image by Angela Radulescu, via Wikimedia Commons

If you’re anything like me, you yearn to become a good writer, a better writer, an inspiring writer, even, by learning from the writers you admire. But you neither have the time nor the money for an MFA program or expensive retreats and workshops with famous names. So you read W.H. Auden’s essays and Paris Review interviews with your favorite authors (or at least PR’s Twitter feed); you obsessively trawl the archives of The New York Times’ “Writers on Writing” series, and you relish every Youtube clip, no matter how lo-fi or truncated, of your literary heroes, speaking from beyond the grave, or from behind a podium at the 92nd Street Y.

Well, friend, you are in luck (okay, I’m still talking about me here, but maybe about you, too). The Washington, DC-based non-profit Academy of Achievement—whose mission is to “bring students face-to-face” with leaders in the arts, business, politics, science, and sports—has archived a series of talks from an incredibly diverse pool of poets and writers. They call this collection “Creative Writing: A Master Class,” and you can subscribe to it right now on iTunes and begin downloading free video and audio podcasts from Nora Ephron, John Updike, Toni Morrison, Carlos Fuentes, Norman Mailer, Wallace Stegner, and, well, you know how the list goes.

The Academy of Achievement’s website also features lengthy profiles–with text and downloadable audio and video–of several of the same writers from their “Master Class” series. For example, an interview with former U.S. poet-laureate Rita Dove is illuminating, both for writers and for teachers of writing. Dove talks about the aversion that many people have for poetry as a kind of fear inculcated by clumsy teachers. She explains:

At some point in their life, they’ve been given a poem to interpret and told, “That was the wrong answer.” You know. I think we’ve all gone through that. I went through that. And it’s unfortunate that sometimes in schools — this need to have things quantified and graded — we end up doing this kind of multiple choice approach to something that should be as ambiguous and ever-changing as life itself. So I try to ask them, “Have you ever heard a good joke?” If you’ve ever heard someone tell a joke just right, with the right pacing, then you’re already on the way to the poetry. Because it’s really about using words in very precise ways and also using gesture as it goes through language, not the gesture of your hands, but how language creates a mood. And you know, who can resist a good joke? When they get that far, then they can realize that poetry can also be fun.

Dove’s thoughts on her own life, her work, and the craft of poetry and teaching are well worth reading/watching in full. Another particularly notable interview from the Academy is with another former laureate, poet W.S. Merwin.

Merwin, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, discusses poetry as originating with language, and its loss as tantamount to extinction:

When we talk about the extinction of species, I think the endangered species of the arts and of language and all these things are related. I don’t think there is any doubt about that. I think poetry goes back to the invention of language itself. I think one of the big differences between poetry and prose is that prose is about something, it’s got a subject… poetry is about what can’t be said. Why do people turn to poetry when all of a sudden the Twin Towers get hit, or when their marriage breaks up, or when the person they love most in the world drops dead in the same room? Because they can’t say it. They can’t say it at all, and they want something that addresses what can’t be said.

If you’re anything like me, you find these two perspectives on poetry—as akin to jokes, as saying the unsayable—fascinating. These kinds of observations (not mechanical how-to’s, but original thoughts on the process and practice of writing itself) are the reason I pore over interviews and seminars with writers I admire. I found more than enough in this archive to keep me satisfied for months.

We’ve added “Creative Writing: A Master Class” to our ever-growing collection of Free Online Courses.

Image via Angela Radulescu

Josh Jones is a doctoral candidate in English at Fordham University and a co-founder and former managing editor of Guernica / A Magazine of Arts and Politics.

Related Content:

William S. Burroughs Teaches a Free Course on Creative Reading and Writing (1979)

Seven Tips From William Faulkner on How to Write Fiction