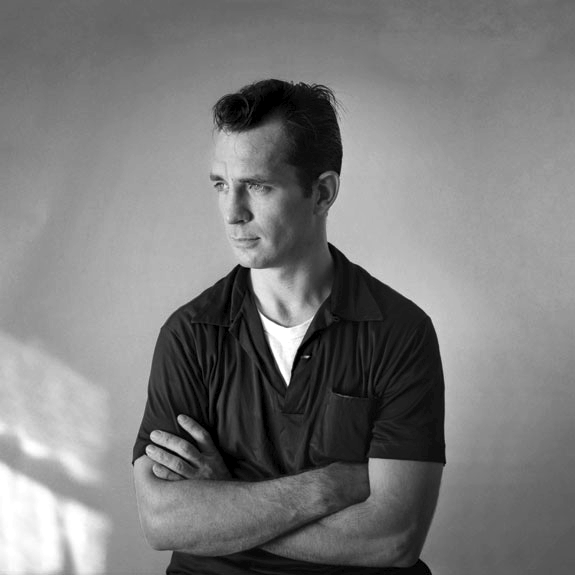

Image by Tom Palumbo, via Wikimedia Commons

Jack Kerouac is the patron saint of every starry-eyed, born-too-late, wanderlusty hipster scribe who falls in love with the poetry and visionary power of their own inner voice. I may be old and crusty now, but I once fell under Kerouac’s spell and spilled my guts unedited into long rambling prose-poems on existential bliss and tantric Buddhist bebop. Then later I realized something: Kerouac’s Kerouac was very good. My Kerouac? Not so much. You gotta do your own thing. I grew out of Kerouac’s influence and didn’t take much of him with me. Then I realized that he wasn’t always good. That he’d made the mistake of every self-proclaimed genius and stopped letting people tell him “no.” He said so himself, in a 1968 Paris Review interview with Ted Berrigan in which he admitted that all his editors since the great Malcolm Cowley, “had instructions to leave my prose exactly as I wrote it.” Now I know this was part of his method, but sometimes the later Kerouac needed a good editor.

It is a delicate dance, between the inner voice and outer editor—whether that taskmaster is oneself or someone else—and the great attraction to Kerouac is his damn-it-all attitude toward tasks and masters. His improvisational prose is the point (I’m sure someone will tell me I missed it).

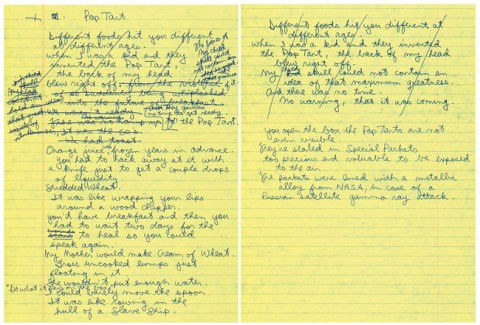

Kerouac doesn’t just write about freedom, he writes freedom, and for most of us tight-assed worrywarts, his voice is healing balm for our writer’s inner excoriations. 1957’s On the Road is an incredible experiment in process as product (it’s not only a novel, it’s an art object)–a three-week burst of non-stop, uninhibited creativity, so legend has it, and unequaled in his lifetime. And yet despite his aversion to tidiness, Kerouac, like almost every writer, made lists; one in particular is thirty guidelines he called “Belief & Technique for Modern Prose.” I’ve excerpted what I think are ten highlights below, either because they seem profoundly beautiful or profoundly silly, but in a way that only Kerouac the holy fool could get away with. This is not “advice for writers.” It’s a catalog of states of being.

1. Scribbled secret notebooks, and wild typewritten pages, for yr own joy

2. Submissive to everything, open, listening

3. Try never get drunk outside yr own house

4. Be in love with yr life

5. Something that you feel will find its own form

6. Be crazy dumbsaint of the mind

7. Blow as deep as you want to blow

8. Write what you want bottomless from bottom of the mind

9. The unspeakable visions of the individual

10. No time for poetry but exactly what is

11. Visionary tics shivering in the chest

12. In tranced fixation dreaming upon object before you

13. Remove literary, grammatical and syntactical inhibition

14. Like Proust be an old teahead of time

15. Telling the true story of the world in interior monolog

16. The jewel center of interest is the eye within the eye

17. Write in recollection and amazement for yourself

18. Work from pithy middle eye out, swimming in language sea

19. Accept loss forever

20. Believe in the holy contour of life

21. Struggle to sketch the flow that already exists intact in mind

22. Dont think of words when you stop but to see picture better

23. Keep track of every day the date emblazoned in yr morning

24. No fear or shame in the dignity of yr experience, language & knowledge

25. Write for the world to read and see yr exact pictures of it

26. Bookmovie is the movie in words, the visual American form

27. In praise of Character in the Bleak inhuman Loneliness

28. Composing wild, undisciplined, pure, coming in from under, crazier the better

29. You’re a Genius all the time

30. Writer-Director of Earthly movies Sponsored & Angeled in Heaven

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Josh Jones is a writer and musician. He recently completed a dissertation on land, literature, and labor.

Related Content:

Jack Kerouac Lists 9 Essentials for Writing Spontaneous Prose