Everyone from Kurt Vonnegut to Ernest Hemingway has shared his ideas on crafting solid narrative writing. One of the most recent sages to join the canon is Emma Coates, Pixar’s former story artist. Her list of the 22 Rules of Good Storytelling gleaned on the job has been gaining Internet traction since it was published last June.

Twenty two? That’s twenty more than Tolstoy. I know some people enjoy a lot of direction, but those of us who relish bushwhacking start to chafe when the road is that heavily signposted.

By all means, sample Coates’ Pixar 22 (see them all below). Apply any and all that work for you, though don’t get your hopes up if your ultimate goal is to sell a story to Dreamworks or Disney. They’ve got formulas of their own.

As for myself, I am repurposing #4 — the only rule that doesn’t contain an implied order or some derivative of “you” — as an extremely jolly parlor game.

Here it is in its original form:

Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___.

While it’s entirely possible to fill in those blanks with the fruits of your own imagination, it’s a true joy to subject one’s most cherished literary, cinematic, and dramatic works to this retroactive Mad Lib. (It works pretty well with established religions too, but I’m not here to tread on the faithful’s toes.)

Warning: there are some major spoilers below. Now that that’s out of the way, let the guessing begin!

Once upon a time there was a poor family in Oklahoma. Every day, they tried to make it work on their hardscrabble farm. One day their last speck of top soil blew away. Because of that, they decided to seek a better life in California. Because of that, every able bodied young male left the family. Until finally their oldest daughter ends up breastfeeding a starving stranger.

How about this?

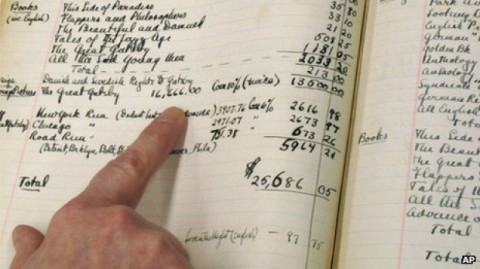

Once upon a time there was a poor young soldier. Every day, he dreamed of rising above his station. One day he met a beautiful rich girl named Daisy. Because of that, he bought a mansion where he threw enormous parties. Because of that, he hooked back up with Daisy. Until finally, he gets shot to death in his pool.

There’s no denying that it fits this one like a glove:

Once upon a time there was a kid. Every day, he played with his cowboy doll. One day he got a spaceman doll. Because of that, his interest in the cowboy took a serious nosedive. Because of that, the cowboy and the spaceman each swore vengeance upon the other’s house. Until finally there’s a bloodbath from which no one emerges unscathed.

I could keep go on forever, but I don’t want to come off as a toy hog. Instead, I invite you to share your filled out Number Fours in the comments section…or tell us which of the other twenty-one seem most suited to its intended purpose.

Pixar’s 22 Rules for Storytelling

#1: You admire a character for trying more than for their successes.

#2: You gotta keep in mind what’s interesting to you as an audience, not what’s fun to do as a writer. They can be v. different.

#3: Trying for theme is important, but you won’t see what the story is actually about til you’re at the end of it. Now rewrite.

#4: Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___.

#5: Simplify. Focus. Combine characters. Hop over detours. You’ll feel like you’re losing valuable stuff but it sets you free.

#6: What is your character good at, comfortable with? Throw the polar opposite at them. Challenge them. How do they deal?

#7: Come up with your ending before you figure out your middle. Seriously. Endings are hard, get yours working up front.

#8: Finish your story, let go even if it’s not perfect. In an ideal world you have both, but move on. Do better next time.

#9: When you’re stuck, make a list of what WOULDN’T happen next. Lots of times the material to get you unstuck will show up.

#10: Pull apart the stories you like. What you like in them is a part of you; you’ve got to recognize it before you can use it.

#11: Putting it on paper lets you start fixing it. If it stays in your head, a perfect idea, you’ll never share it with anyone.

#12: Discount the 1st thing that comes to mind. And the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th – get the obvious out of the way. Surprise yourself.

#13: Give your characters opinions. Passive/malleable might seem likable to you as you write, but it’s poison to the audience.

#14: Why must you tell THIS story? What’s the belief burning within you that your story feeds off of? That’s the heart of it.

#15: If you were your character, in this situation, how would you feel? Honesty lends credibility to unbelievable situations.

#16: What are the stakes? Give us reason to root for the character. What happens if they don’t succeed? Stack the odds against.

#17: No work is ever wasted. If it’s not working, let go and move on — it’ll come back around to be useful later.

#18: You have to know yourself: the difference between doing your best & fussing. Story is testing, not refining.

#19: Coincidences to get characters into trouble are great; coincidences to get them out of it are cheating.

#20: Exercise: take the building blocks of a movie you dislike. How d’you rearrange them into what you DO like?

#21: You gotta identify with your situation/characters, can’t just write ‘cool’. What would make YOU act that way?

#22: What’s the essence of your story? Most economical telling of it? If you know that, you can build out from there.

via BoingBoing

- Ayun Halliday was not raised to question authority.